Adapted from “Burundi: The anatomy of mass violence endgames” by Noel Twagiramungu in How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq, ed Bridget Conley (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

A military elite whose influential members hailed from the hitherto obscure Hima clan, a Tutsi sub-group from the province of Bururi, dominated Burundi’s post-colonial political scene—though Tutsi represents only 14% of the population while Hutu comprise 85%. For Burundi’s ruling elite, 1972 was a year of all kinds of dangers: rumor spread that Hutu refugees were plotting an invasion from exile; several Tutsi leaders, notably Banyaruguru from the north of the country, were increasingly expressing discontent with the Bururi Lobby’s nepotism; and western powers, including Belgium and the United States were suspected of helping the ousted king, Ntare III Ndizeye, in a bid to return to power in Bujumbura. To meet the threats head-on, the regime abducted former king Ndizeye from Uganda on March 30, 1972, and ordered his execution on April 29. This fateful execution divided the government, which was dismissed by President (Captain) Michel Micombero (1965-1976) the same day. As the rumors of regime collapse and regicide spread, armed Hutu groups, made of the elements who had fled to Tanzania in the wake of earlier periods of violence in 1965 and 1969, judged the situation ripe for an insurgency.[i]

Atrocities (1972)

The insurgency launched deadly attacks in the southern part of Burundi. Throughout their attacks from the Nyanza-lac and Rumonge in the south to Bujumbura in the west and Cankuzo in the east, “the insurgents proceeded to slaughter every Tutsi in sight, as well as a number of Hutu who refused to join the rebellion.”[ii] Within a matter of three days, the insurgents proclaimed a “People’s Republic” headquartered in the Vugizo commune (Bururi). By the end of April, when the army began to crush the insurgents and thus bringing the short-lived Hutu republic to an end, up to 3,000 people, most of them Tutsi, had perished.

On April 30, 1972, President Micombero dismissed the civilian governors and replaced them with military commanders. The following day, he declared a state of emergency, restricting freedom of movement and assembly. Over the next weeks, the army carried out a systematic, methodic and brutal pogrom meant to “decapitate the Hutu leadership”[iii] throughout the country. The resulting mass violence marks 1972 as the darkest year in the history of Burundi.[iv] One scholar sums up the unfolding horrors, stating:

On May 30, while vigorous counterattacks were being launched against the insurgents, elements of the armed forces and the JRR [Jeunesse Républicaine Rwagasore] began to coordinate their efforts to exterminate all Hutu suspected to have taken part in the rebellion. Martial law was proclaimed throughout the country, and a dawn-to-dusk curfew was enforced. Within Zairian paratroopers holding the airport, the Burundi army then moved into the countryside. What followed was not so much a repression as a hideous slaughter of Hutu populations. The carnage continued unabated until August. By then, almost every educated Hutu was either dead or in exile.[v]

Fatalities

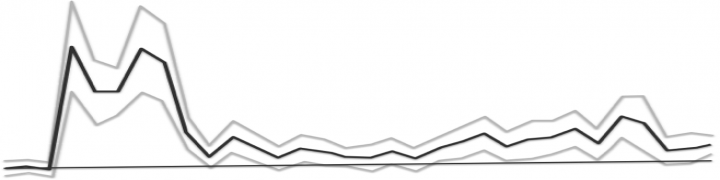

The range of fatality estimates for this period of violence is broad: 80,000[vi] to 300,000.[vii] Based on current research, we estimate that the number is around 100,000.[viii]

Endings

On July 14, 1972, a new government was sworn-in and tasked to “restore order.” In early August 1972, the newly appointed Prime Minister, Albert Nyamoya, along with several members of his government toured the country, “spreading the message of peace, national reconstruction and unity.”[ix] On August 22, 1972, the emergency decrees were abrogated and the military governors replaced by the civilian ones.

On August 31, 1972, the Catholic Bishops of Burundi met with Prime Minister Nyamoya to discuss normalizing the situation. a priest who attended the meeting reported that, “after the two parties harmonized their views on a number of issues including order and security in the countryside, justice, emergency aid to widows and orphans, and, the problem of IDPs and refugees, the church spread out the good news that ‘the nightmare was over.’”[x] For the next 16 years, life returned to normalcy, albeit in a quasi-apartheid regime dominated by Tutsi army officers from Bururi and in which the Hutu populations were considered second-class citizens.

Coding:

We coded this case as ending ‘as planned,’ through a process of normalization, accompanied by a change in leadership. As secondary influence on the ending, we note the moderating impact of domestic actors. The primary perpetrators, the State, largely met their goals of using violence, but we code for multiple victim groups to account for assaults against both Tutsi and Hutu civilians.

Works Cited

This case study is adapted from Noel Twagiramungu’s “Burundi: The anatomy of mass violence endgames” in How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq, ed. Bridget Conley-Zilkic, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Lemarchand, René. 1995. Burundi: Ethnic conflict and Genocide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Malkki, Liisa. 1995. Purity and Exile: Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology Among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Uvin, Peter. 2009. Life After Violence: A People’s Story of Burundi. London: Zed Books.

Notes

[i] Twagiramungu 2016, 62.

[ii] Lemarchand 1995, 91.

[iii] Twagiramungu 2016, 63.

[iv] For Hutu refugees’ accounts, see Malkki 1995.

[v] Lemarchand 1995, 91.

[vi] Uvin 2009.

[vii] Larmarchand 1995.

[viii] Twagiramungu 2016, 60.

[ix] Twagiramungu 2016, 63.

[x] Twagiramungu 2016, 63.