This case study is an adaptation of “Sudan: Patterns of violence and imperfect endings” by Alex de Waal in How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq, ed Bridget Conley (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

Significant conflicts occurred in Darfur over the fifteen years prior to the globally recognized insurrection that erupted in February 2003.[i] Darfur’s conflicts included different configurations of the following factors: local ethnic disputes, spillover of the Chadian civil war, Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) incursion from southern Sudan, and government overreaction to local rebellion, especially by mobilizing proxy militia forces.

The 2003 rebellion was more significant than its predecessors because of the large-scale involvement of Chadian army officers in supporting the rebels; the extensive military supplies provided by the SPLA (which was at the time negotiating a peace agreement with Khartoum) to the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA); the emergence of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) drawn from former Darfurian Islamists suspected of having ties to would-be putschists in Khartoum; and the extent to which local state officials were backing and arming Arab militia. After the rebels overran Darfur’s main airbase in April 2003, the government decided on a military response at scale. True to form, it used proxy militia in the frontline of its offensives, in this case drawn principally from camel-herding Arab tribes, and popularly known as janjawiid.

Atrocities

From June 2003 to January 2005, Sudanese Armed Forces, militia and airforce mounted three vast scorched earth offensives in Darfur. The main method of the forces was targeting civilian communities, especially Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa, the groups that formed the mainstay of the SLA and JEM. The scorched earth tactics, which included killing, rape, torture, looting, and arson of entire villages, combined with obstruction of relief.

Fatalities:

Most attempts to gauge the severity of the Darfur campaigns refer to numbers of those who died as part of the humanitarian disaster. CRED has attempted to quantify the number of people killed by “assembling every reliable data source” reporting on the conflict, they write:

“In total, we calculate that 134,000 people died between September 2003 and January 2005, with 35,000 violent deaths concentrated in localised areas and over short periods of time. The majority of deaths – about 99,000 – were due to disease and malnutrition.”[ii] (emphasis added).

Given that the conflict began in April 2003 (several months previous to the above study), and that there is a high likelihood of some fatalities not being reported, we include Darfur with an upper threshold of 50,000 civilians killed between 2003 – 2005.

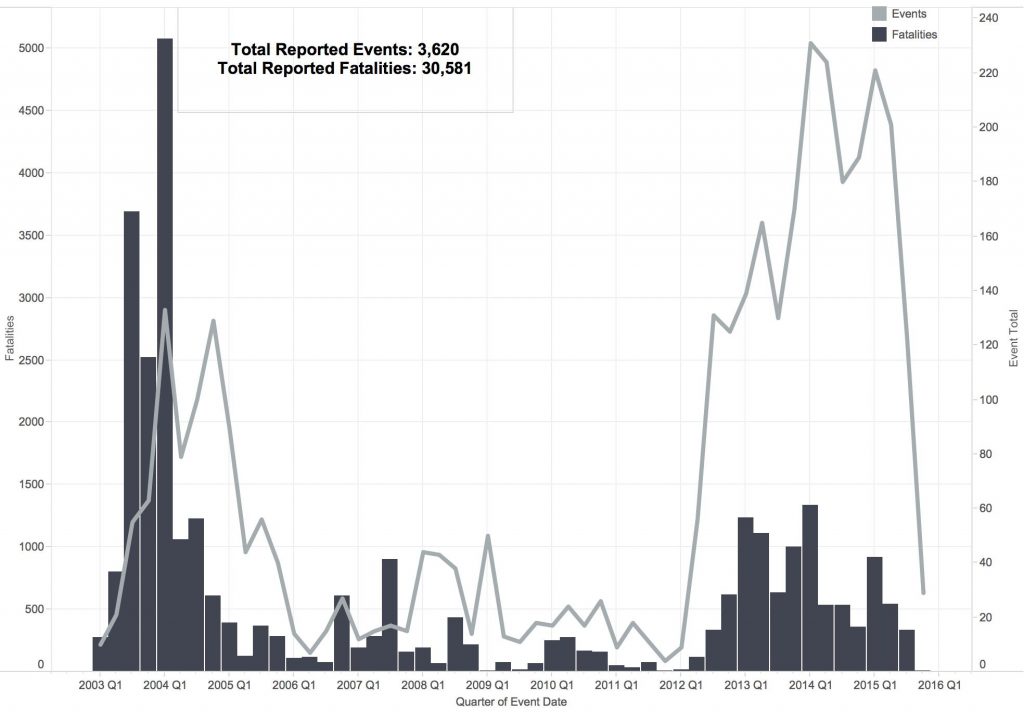

Figure 3: Violent incidents and fatalities in Darfur 2003-14

Source: ACLED. Note that the figures are certainly an underestimation for 2003 and early 2004.

Ending

The first and most dramatic drop in the number of killings in Darfur coincided with the end of the government’s second major offensive and the signing of the N’djamena Humanitarian Ceasefire Agreement in early April 2004. The government had achieved its principal military objectives and the army had reached the limits of its immediate operational capacity, having exhausted its supplies.

International pressure was also a factor. The U.S. administration had been alerted early to the Darfur war and its humanitarian implications, and a major USAID response was underway in the second half of 2003. A political response from the U.S. was slower, but by March 2004, the U.S. was actively backing Chadian and African Union initiatives for a ceasefire and peace talks, held in the Chadian capital N’djamena. These efforts climaxed, coincidentally, in early April 2004, just as the AU held a day of commemoration for the tenth anniversary of the Rwanda genocide. The AU Chairperson, Alpha Oumar Konaré, met President Bashir and urged him to sign a ceasefire at once. Bashir passed his instruction to his negotiator in N’djamena, Major-General Ismat al Zain. Ismat responded that another few days’ talks were required to resolve a key issue over where the rebels would be located during the ceasefire and adopt a map.[iii] Ismat was overruled, but his reservation was prescient: the absence of an agreed map made the ceasefire impossible to enforce, and the SLA groups headed by Minni Minawi decided to expand the war to eastern and southern Darfur shortly thereafter, sparking a third large-scale government counteroffensive.

The ceasefire, albeit only partially respected, allowed for a rapid scale up in humanitarian operations. This was possible only because of the initiative taken by senior officials at USAID (Andrew Natsios and Roger Winter) eight months earlier. The data for general mortality in Darfur, overwhelming caused by hunger and disease, indicates that it fell more rapidly than in other comparable crises, reaching levels approximately equal to normal by the end of 2005. The credit for this success belongs to the early USAID response and the ceasefire.

The third government campaign, between June 2004 and January 2005, was just as large as the previous ones, but both less bloody and less militarily successful. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that one reason for the reduced level of killing of civilians was the presence of military observers, mostly Africans but also some Europeans and Americans, as part of the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS) set up by the N’djamena agreement. The AMIS Force Commander was also proactive, both in deploying his troops, often stretching his mandate, and his public pronouncements. Although AMIS later came in for serious criticisms for its inadequacies, its first deployment coincided with a substantial reduction in both fighting and one-sided violence, and the third army campaign killed many fewer civilians. At the same time, an enormous international humanitarian effort was gearing up, with a much-increased presence of aid workers. This had been set in motion by USAID in mid-2003. The aid that began to arrive six months later undoubtedly saved many lives and there is also anecdotal evidence that the presence of aid workers served as a deterrent to mass killing.

The second drop in levels of killing occurred in January 2005, when that campaign ended. This also followed the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the Government of Sudan and the SPLM/A, and John Garang’s subsequent commitment to assist in resolving the Darfur conflict. Displacement continued for considerably longer, though the reasons for people leaving their villages became more complex, less to do with mass attack and more to do with generalized insecurity and collapse of the rural economy.

The situation thereafter was one of a low-intensity conflict, with the rebel groups fragmenting and occasionally fighting one another, and the government’s erstwhile proxies losing their enthusiasm for the war and either becoming freelance, turning on one another, or turning their guns on the government. The conflict after 2005 consisted of a mixture of banditry, inter-ethnic conflict, harassment of civilians including displaced persons, and occasional offensives and counteroffensives by government and rebels.[iv]

Coding

We code this case as ending ‘as planned’ by the Sudanese government through a process of normalization. We note that nonstate actors were a secondary perpetrator to include militias aligned with the government and rebel abuses, and also note the influence of international moderating forces.

We allow for a secondary coding of this case as a ‘strategic shift,’ to capture dynamics whereby international attention may have influenced the Sudanese government’s reduced reliance on atrocities to achieve their goals.

Works Cited

Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). 2103. “People Affected by Conflict: Humanitarian Needs In Numbers,” Brussels: CRED. Available at http://www.cred.be/publications Accessed 10 April 2015.

de Waal, Alex. 2016. Sudan: Patterns of violence and imperfect endings” in How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq, ed Bridget Conley-Zilkic. How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq. New York: Cambridge University Press.

de Waal, Alex and Chad Hazlett, Christian Davenport, and Joshua Kennedy. 2014. “The epidemiology of lethal violence in Darfur: Using micro-data to explore complex patterns of ongoing armed conflict,” Social Science and Medicine 120:368-377. Accessed January 20, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.035.

Flint, Julie and Alex de Waal. 2008. Darfur: A New History of a Long War. London: Zed.

Notes

[i] Flint and de Waal 2008.

[ii] Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) 2103, 29.

[iii] de Waal 2016, 134 – 135.

[iv] de Waal, Alex and Chad Hazlett, Christian Davenport, and Joshua Kennedy 2014.