It’s that time of year again to get out of the lab, into the sun, and show off your program pride: the Sackler Relays are here! As you are all bringing your A-game to the fields of Medford this Friday, the Insight Newsletter team decided to step up to the plate and help get everyone pumped for a great day of fun and friendly competition by outlining what the GSC has put together for everyone this year.

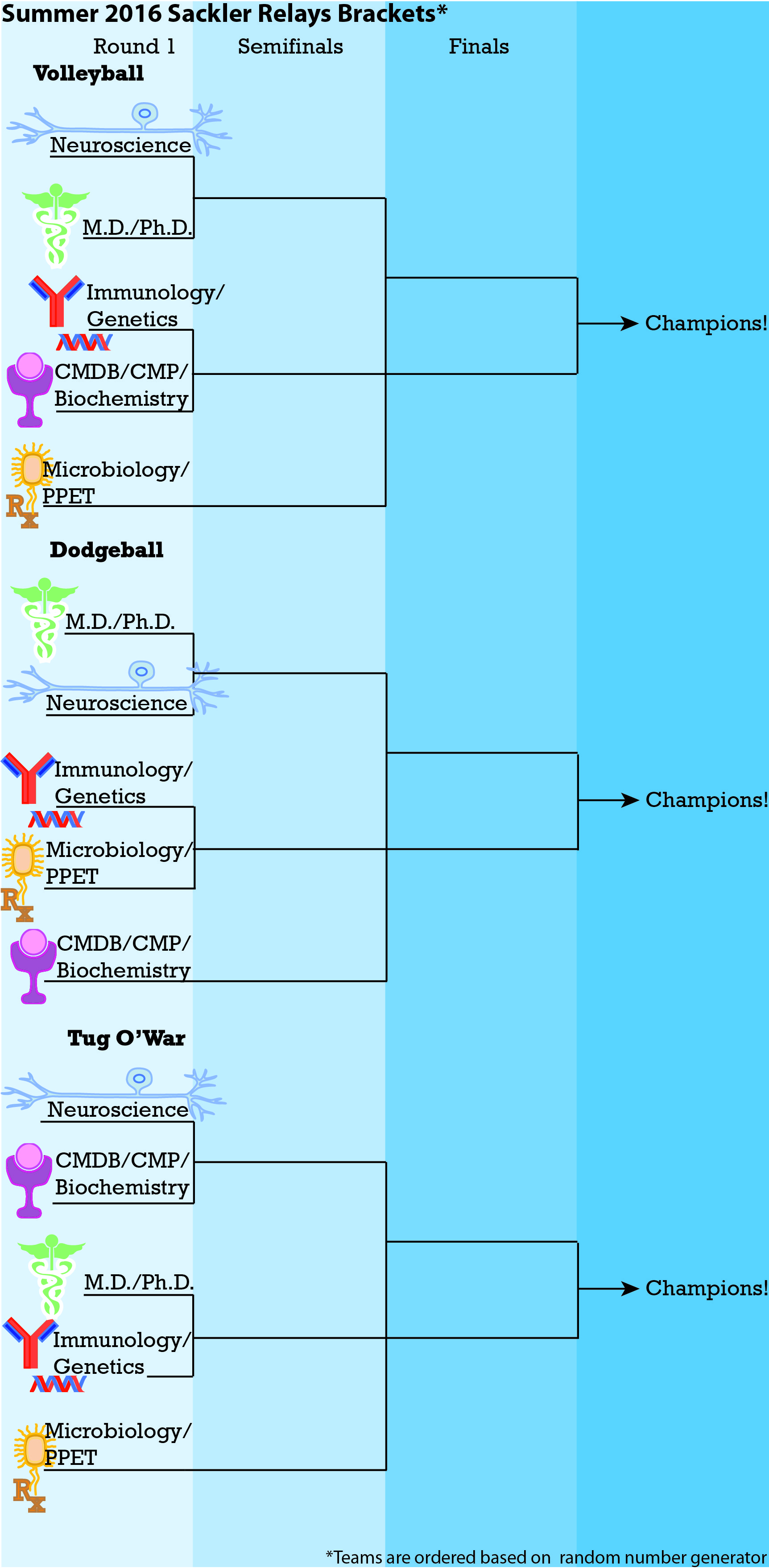

First up: the teams! We have some programs joining forces, with Biochemistry, CMP, and CMDB merging together into a new program and thus a new team for this year’s Relays. Immunology and Genetics are also going for some cooperative action, as well as Microbiology and PPET. And lastly (but not least), let’s see if this year’s new MD/PhD team can put some pressure on last year’s Neuroscience champions.

The GSC has a classic event lineup planned (see below), with a BBQ lunch and raffle scheduled as well. The proceeds from that event will go towards the Sackler Student Enrichment Fund, which provides support for students to present research at scientific conferences or attend career development events.

- 12:00-1:00 pm Arrival at Medford Field

- 1:00-1:30 pm Running events (4 x 200m relay, 100m dash, 800m dash)

- 1:30-2:30 pm Lunch and raffle

- 2:30-4:00 pm Volleyball, dodgeball, obstacle course

- 4:00-4:30 pm Water balloon toss

- 4:30-5:00 pm Tug of war

- 5:00 pm **Announcement of final scores

Scoring is point-based per event, with increasing points awarded the higher the team placement for the event (Table 1). The scoring for the obstacle course is time-based, while the volleyball, dodgeball and tug-of-war events are scored based on single-elimination tournaments (see graphic for brackets). Total points are tallied from all Relay events as well as points awarded from the March Madness bracket competition to determine the winning team.

Table 1. Scoring scheme for the 21st Annual Sackler Relays.

| 2 x 400m relay*, 100m dash**, Half mile* | Volleyball*, Dodgeball*, Obstacle Course, Water Balloon Toss, Tug of War*** | |

|

1st |

8 | 16 |

| 2nd |

6 |

12 |

| 3rd |

4 |

8 |

| 4th | 1 |

4 |

| 5th | 1 |

1 |

* There must be at least one male and one female competing.

** Separate heats for males and females.

*** Teams must come to an agreement regarding # of each gender participating based on available members of each team.

Get excited Sackler, and see you on Friday!

![IMG_20160713_204129_894[1]](https://sites.tufts.edu/insight/wp-content/blogs.dir/2889/files/2016/07/IMG_20160713_204129_8941-169x300.jpg)