The Arctic and the LOSC

Introduction

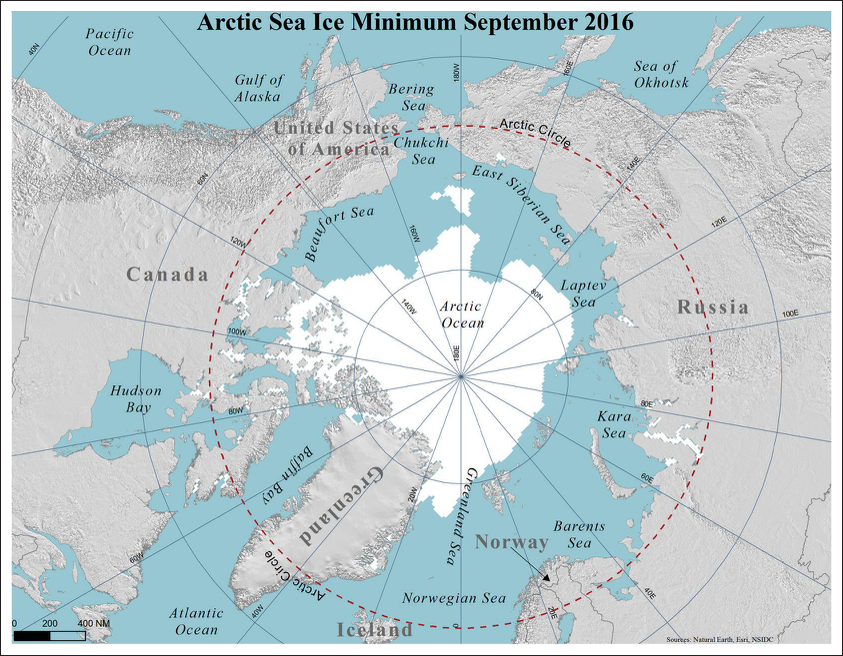

Due to the effects of climate change on melting ice, the Arctic has captured new levels of international attention. In the past, this remote and inhospitable region was almost entirely inaccessible due to year-round sea ice. As warming melts the sea ice, parts of the Arctic Ocean will increasingly open. While the thawing of the Arctic sea ice and glaciers raises serious environmental issues, the opening of the region will likely lead to new economic opportunities. By the middle of the present century, the retreat of ice will potentially open new shipping lanes and the possibility of new resource extractions.

Potential access to new resources has led to increased interest among States and observers regarding exactly who owns what in the Far North. Unlike Antarctica, which is a largely uninhabited continent with unsettled sovereignty questions, coastal States ring the Arctic with established boundaries. In the Arctic Ocean, the LOSC provides a clear framework for determining boundaries and legal rights and responsibilities.

No Race for the North

At times, media reports on the Arctic have depicted an unclaimed wilderness with States scrambling for resources.1 In 2007, some people’s fears were stoked when Russian scientists symbolically planted a titanium Russian flag at the North Pole.2 In reality, the Arctic is not likely to be a source of conflict over territorial claims. This is because, with the exception of a small island between Canada and Greenland, there are no unresolved land border disputes in the Arctic. Furthermore, the Arctic coastal States – the U.S., Canada, Russia, Denmark, and Norway – jointly declared in 2008 that the LOSC was the appropriate framework for Arctic governance.3 Thus, as with the rest of the oceans, the LOSC provides a clear legal regime for the Arctic.

Coastal State Rights

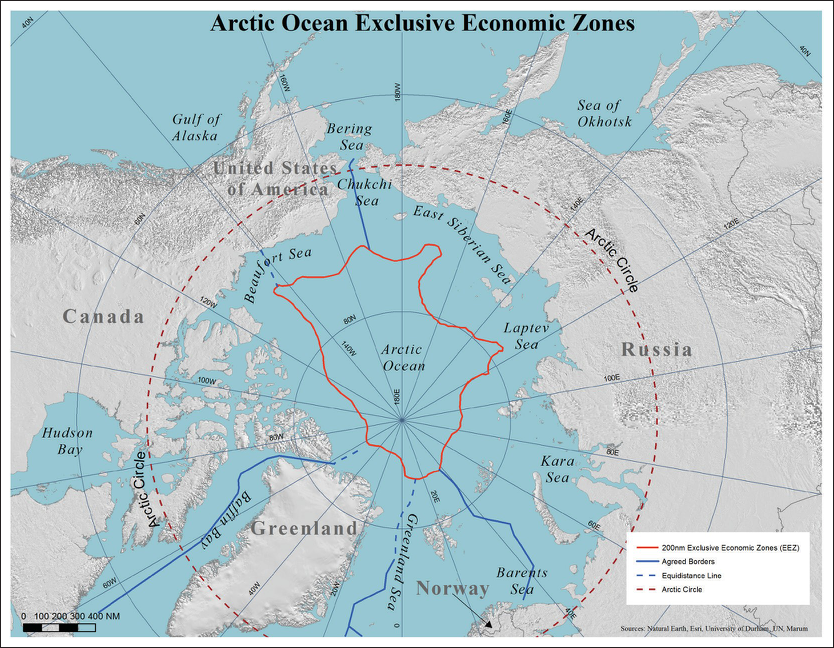

Much of the Arctic Ocean falls under the jurisdiction of the coastal States. As outlined in Chapter Two: Maritime Zones, coastal States enjoy a 12 nautical mile territorial sea and a 24 nautical mile contiguous zone. In addition, coastal States may declare an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles from the baseline, in which they have the right regulate the use of natural resources and establish environmental protection. While some overlapping claims exist, the Arctic coastal States have mostly resolved maritime boundary disputes through bilateral negotiations. The most significant unresolved maritime boundary dispute is between the U.S. and Canada in the Beaufort Sea. However, both parties seek to minimize tension as they work toward resolving the dispute. In reality, issues of sovereignty in the Arctic are relatively clear and not contentious.

LOSC Article 234 – Special Rights for Arctic Coastal States

The LOSC, in Article 234, grants coastal States authority to specially regulate ice covered areas within their national jurisdiction.4 They may adopt nondiscriminatory regulations focused on the prevention, reduction, and control of marine pollution in areas of the EEZ covered by ice most of the year where the ice presents an obstruction or exceptional hazard to navigation. The rules must be based on the best available science and must have “due regard for navigation.”5 Notably, Canada and Russia have exercised this regulatory privilege.

The application of Article 234 is a subject of dispute between the U.S. and the other Arctic coastal States. Canada and Russia assert they have the right to exclude ships from their territorial sea or EEZ if States fail to comply with local regulations enacted pursuant to Article 234. The U.S. agrees that coastal States may enact regulations, but asserts that because of the freedom of the high seas, innocent (or transit) passage may not be impeded by excluding vessels pursuant to Article 234.6

In response, Canada and Russia cite Article 34, which clarifies that that transit passage “does not affect the legal status of the waters forming such straits or the exercise by the States bordering the straits of their sovereignty or jurisdiction over such waters and their air space, bed and subsoil.”7 Additionally, the innocent passage regime of Article 24 is subject to exception “in accordance with this Convention.” This exception would seem to permit restriction of innocent passage based on Article 234 or other provisions in the treaty.8 Reading these limitations of the passage rights within Article 234’s grant of authority to regulate ice covered waters, Canada and Russia assert a right to deny passage in response to violation of their national regulations based on Article 234. The U.S. position is that these exceptions do not justify restriction of passage on the basis of national regulation.

Arctic Continental Shelf

Unresolved overlapping claims on the deep seabed are the only significant territorial disputes between nations in the Arctic. Under the LOSC, coastal States have the right to request a recommendation from the Committee on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) regarding an extension of their continental shelf beyond the 200 nautical mile EEZ. An extension would legally entitle that State to exclusive subsoil resource access on the extended continental shelf. For additional information on this topic see Chapter Two: Maritime Zones. If scientific data collection and analysis corroborates the current projections of the extended continental shelves in the Arctic, nearly all subsoil rights in the Arctic will ultimately fall under the exclusive jurisdictions of States. Successful extension claims in no way affect the legal status of the water column, the ocean surface, or the airspace above the extended continental shelf.

The CLCS has no legal mandate to resolve disputes. The CLCS recommendations are meant to provide an independent assessment of bathometric and geological data submitted by claimants for the extended continental shelf, upon which bilateral decisions can be reached between States. Arctic States are committed to abiding by the LOSC, the recommendations of the CLCS, and “the orderly settlement of any possible overlapping claims.”9 Extended continental shelf claims are disputed in many regions of the world, but the Arctic has the most natural resources under contention by volume.

The Arctic States have followed the procedures of the Convention relating to extended continental shelf claims, and to date no formal determinations by the CLCS have been made. Russia’s claims, and to a lesser extent those of Denmark, would, however, embrace a significant portion of the Arctic seabed. Russia’s claims and interpretations in particular are based on characterizations of geologic and geomorphic features of the Arctic seabed with which the U.S. disagrees.

Arctic Straits

One of the more contentious legal debates among Arctic States is the applicability of the right of transit passage in international straits to the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route. The Northwest Passage is the long-sought sea route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean that passes between Canadian islands in the Far North. The Northern Sea Route is a transit route along the northern coast of Russia. Both routes can shorten voyages between Europe and Asia, but they remain hazardous due to sea ice and weather. Canada and Russia claim these as internal waters where foreign ships do not have the right to go without permission. The U.S. argues that the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route are international straits and consequently the coastal States do not have the right to restrict transit passage. Despite the disagreement, it is important to emphasize that the parties agree that the LOSC is the appropriate framework to utilize to resolve the disputes. They simply disagree regarding the correct interpretation of the LOSC.

In order to be considered an international strait, the International Court of Justice ruled in the Corfu Channel case that a body of water must have a “geographical situation as connecting two parts of the high seas and the fact of its being used for international navigation.”10 International straits are also defined by Articles 37 and 38 of the LOSC. The Corfu channel was traversed by 2,884 ships within a twenty one month period. While the Northwest Passage has seen only a small handful of ships until very recently, the Corfu Channel court stated the “greater or lesser importance for international navigation” was not important so long as the strait is a “useful route” for international maritime traffic. As the ice in the Northwest Passage melts it will certainly be “useful” to international navigation and “used” more frequently. Indeed, ship traffic has already begun in the Northwest Passage. 11

Canada asserts that the Northwest Passage is part of Canadian internal waters and is therefore sovereign Canadian territory and not subject to either the transit passage or innocent passage rights of other nations. Canada justifies this assertion with straight baselines drawn in 1985 based on the claim that “historic usage” by the Inuit people of the ice covered waterways for hundreds of years establishes the area as Canadian sovereign territory.12 However, there is arguably no clear legal authority for “historic usage” to establish sovereignty over water. The U.S. has consistently protested Canada’s use of straight baselines for this purpose and its assertion that the enclosed waters are internal.

Russia also asserts that portions of the Northern Sea Route are internal waters. The U.S. argues, as in the Northwest Passage, that the usefulness of the strait for international navigation is the deciding factor, regardless of the actual volume of traffic. Like Canada, the Russian position is also based on historical usage and lack of transits without prior authorization. The U.S. made several attempts to navigate the straits without permission, but turned back in the face of Russian threats.

Nonetheless, the U.S. has consistently disputed Russia’s claims. These disputes have not recently been a source of tension. In the Northwest Passage, the U.S. and Canada have “agreed to disagree” over the status of the strait. The U.S. has not attempted a transit in the Northern Sea Route without Russian permission. Nonetheless, as the straits are increasingly open to shipping, other States with an interest in shipping may join the U.S. in contesting the Russian and Canadian claims. Eventually, the claims may be resolved through negotiation or some other dispute resolution method.13

Arctic High Seas

Even if all or most of the Arctic seabed belonged to one State or another’s continental shelf, there will still be a portion of the central Arctic Ocean water column that is beyond the jurisdiction of any coastal States. This area is the Arctic high seas. Other States would have the right to freely navigate and exploit the resources in the water column in this part of the high seas. Many are concerned that living marine resources in the central Arctic Ocean will be subjected to dangerous and unregulated fishing.

In the future, the Arctic States in coordination with other fishing States may decide to establish a regional fisheries management organization. This association would function as a treaty organization designed to coordinate and manage fishing stocks in a sustainable way to advance mutual interests. For now, the five Arctic Coastal States released a joint declaration at Oslo, Norway in the summer of 2016 directed towards fishing in the central Arctic Ocean. The declaration noted that commercial fishing in the central Arctic Ocean was not currently feasible and so a regional fishery management organization was not yet necessary. Regardless, the coastal States undertook as an interim measure to restrain any fishing in the central Arctic Ocean until a fishing regulatory scheme like a regional fisheries management organization could be established. This decision ensures that future fishing will be carried out sustainably and in accordance with scientific inputs. The coastal States also declared their intent to respect the rights of other States and to pursue their cooperation in achieving a mutually beneficial preservation of Arctic fish stocks.14 It is likely that Arctic fishing will continue to be a topic of interest and further regulation as central Arctic fishing grounds open in the years ahead.

The Arctic Council

While the LOSC sets the framework of governance in the Arctic, there are areas where additional rule-making among the Arctic States is necessary. Because of the inhospitable nature of the region, the general lack of State assets and capabilities in the area, and the sensitivity of the environment, cooperation among the Arctic States is essential. To that end, the Arctic States – the five Arctic coastal States plus Sweden, Finland, and Iceland – established the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council acts as a forum for cooperation and coordination among the Arctic States, but it is not a true international organization with rule-making power. All decision-making is done on a consensus basis, and treaties negotiated in the Council are enacted between the Arctic States without reference to the Council as a legal entity. Other nations with interests in the opening Arctic, like China, have observer status on the Council, but they don’t have full membership.

So far, the Council has been the forum for negotiating two significant treaties between the Arctic States. First, in 2011, the Arctic States signed a treaty on search and rescue, apportioning responsibility for response and structuring cooperation. Then, in 2013, the Arctic States signed a treaty on Arctic pollution preparedness and response.15 A third treaty focused on scientific research and cooperation was signed on May 2017.16 These agreements demonstrate the utility of a standing forum for the interested parties to discuss and cooperate in areas of mutual interest.

International Maritime Organization (IMO) Polar Code

One of the more recent developments in Arctic maritime law is the promulgation of a polar shipping code by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). This Polar Code sets additional standards for construction, manning, training, equipment, voyage planning, pollution, and communications for commercial ships in polar waters. The IMO is the specialized agency of the UN charged with “responsibility for the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine pollution by ships.”17 The Marine Safety Committee and the Marine Environmental Protection Committee of the IMO released resolutions amending the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). Both of these resolutions include additional requirements in order to “reduce the probability of an accident” in the sensitive and remote polar regions.18 While there are IMO codes setting minimum standards that are applicable globally, the Polar Code is needed because ships operating in the polar regions can expect to encounter environmental and navigational challenges beyond those experienced in other regions.

The mandatory provisions of the Polar Code went into effect on January 1, 2017 for new ships. The provisions go into effect for existing ships in 2018. In addition to the mandatory provisions, the Polar Code also includes additional non-binding recommendations for both safety and environmental protection. The Polar Code likely qualifies as “generally accepted international rules and standards” for environmental protection under Article 211 of LOSC. If so, flag States would be responsible for enforcement of the Code and coastal States may demand compliance with its terms.19 In the face of likely increased ship traffic in the future, due to receding ice, the Polar Code will protect the safety of mariners in an inhospitable region and the fragile Arctic environment itself.

Conclusion

The LOSC provides the necessary legal framework for Arctic governance. It establishes a clear set of rights and responsibilities for coastal States and others. Where the general provisions of the LOSC may not be enough to protect mariners and the environment in this inhospitable region, the LOSC provides the pathways for coastal States to regulate ships further. The IMO has begun to increase safety in the region even further as was discussed above.

- See for example, Paul Reynolds, “Russia Ahead in Arctic ‘gold rush,’” BBC News (Aug. 1, 2007), (available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_depth/6925853.stm).

- See for example, Paul Reynolds, “Russia Ahead in Arctic ‘gold rush,’” BBC News (Aug. 1, 2007), (available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_depth/6925853.stm).

- The Ilulissat Declaration, May, 29, 2008, (available at http://www.oceanlaw.org/downloads/arctic/Ilulissat_Declaration.pdf).

- LOSC, Article 234.

- LOSC, Article 234.

- Stanley P. Fields, Article 234 of the United Nations Law of the Sea: The Overlooked Linchpin for Achieving Safety and Security in the U.S. Arctic?, 7 Harv. Nat’l Sec. J. 55, 59-77 (2016).

- LOSC, Article 34.

- LOSC, Article 24.

- Ilulissat Declaration, Arctic Ocean Conference, Ilulissat, Greenland, May 2008, (available at http://www.oceanlaw.org/downloads/arctic/Ilulissat_Declaration.pdf).

- Corfu Channel Case (UK v. Albania) 1949 I.C.J. 4, 28-29 (Apr. 9).

- Corfu Channel Case (UK v. Albania) 1949 I.C.J. 4, 28 (Apr. 9).

- Michael Byers, International Law and the Arctic at 131-32 (2013).

- These disputes between Canada and Russia are summarized in Michael Byers, International Law and the Arctic (2013).

- “Declaration Concerning the Prevention of Unregulated High Seas Fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean”, (Jul. 16, 2015), (available at https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/departementene/ud/vedlegg/folkerett/declaration-on-arctic-fisheries-16-july-2015.pdf ).

- Agreements, Arctic Council (Sep. 16, 2015), (available at http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/our-work/agreements).

- “Task Force on Scientific Cooperation meets in Ottawa, Arctic Council” (Jul 27, 2016), (available at http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/our-work2/8-news-and-events/408-sctf-ottawa-july-2016); “Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation”, U.S. Department of State (May 11,2017), (available at https://www.state.gov/e/oes/rls/other/2017/270809.htm).

- “Introduction to IMO”, IMO, (available at http://www.imo.org/en/About/Pages/Default.aspx).

- Øystein Jensen, “The International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters: Finalization, Adoption, and Law of the Sea Implications”, 7 Arctic Rev. on Law and Politics, no. 1, at 68-69.

- Øystein Jensen, “The International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters: Finalization, Adoption, and Law of the Sea Implications”, 7 Arctic Rev. on Law and Politics, no. 1, at 64-74.