Part One of this essay can be found here.

Monuments to Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis or other Confederate icons tell a different story from that of the American dream of unending expansion of equality and justice. As documented by the Southern Poverty Law Center, the vast majority was erected by those committed to the history of prejudice and racism despite losing the war, by transforming it into the narrative of the Lost Cause. Defeat in battle transformed into a fight to control the peace. While commemoration began in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, monuments to the Lost Cause—many taking the same form of the Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville that was the provocation for the latest events in 2017—sprouted like poisonous mushrooms in the days after a storm. Construction of these symbols of the south surged at the turn of the last century, spiking in 1910 but continuing into the early 1940s, contemporaneous to the imposition of Jim Crow laws across the South.

The monuments must be seen as part of the see-saw of collective action to improve material conditions in Black Americans lives with parallel efforts by those opposed to re-claim symbolic ground through Confederate statues. Thus, construction increased again during a period began in the 1950s and carried through the 1960s, corresponding to the Civil Rights Movement. Today’s pitched efforts to salvage the monuments come in the wake of Black Lives Matter civil activism and the dismantling of Confederate icons following white supremacist Dylann Roof’s lethal assault in 2015 against nine Black members of a peaceful prayer group, assembled at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

The bonds that tie Confederate monument building to Black political activism reveal the secret of the “American dream” – it is reinvigorated by those who most need it and fight to expand its meaning, not those who rest comfortably in the present or lean on a mythologized past. The testimony of its power is that even those who suffered the hypocrisies of the American dream could still find words to forgive the violence and keep the narrative alive. While we often hear of the worst in our communities, examples of this forgiveness exist from coast to coast as well. In Arkansas, for instance, when a white kid spray-painted a swastika across a mosque and later asked for forgiveness, the Muslim community responding by advocating that the Court show mercy. And an astonishing example came in a Courtroom in 2015, when family members of the murdered prayer group turned to Dylann Roof and forgave him. As Wanda Simmons, whose grandfather Daniel Simmons was among those killed, stated: “Although my grandfather and the other victims died at the hands of hate, this is proof, everyone’s plea for your soul, is proof that they lived in love and their legacies will live in love. So hate won’t win. And I just want to thank the court for making sure that hate doesn’t win.”

The depth of courage and faith demonstrated by a Muslim community, the families in Charleston and rights activists across the decades exceeds, thereby replenishes, the possibility for dreaming. The American story withstood the assault against native populations, slavery, periods of intensive intolerance for other minority populations and patriarchy, because it blew like the winds in the trees, above it all, the very air we breathed: you can make it anyway and in doing so, you will make it better for others. Individualism carved out passage for the shared future. The dream carried activists through their darkest days, through struggle and refusal to compromise on the core substance of demands for equality. Those taking to the street, the courtrooms and into public office could mouth the incantation that is the substance of the American example: the merging of self-reliance and collective progress. An American ideology of exceptional potential, endowed to each of its citizens, elevating the country above all others.

***

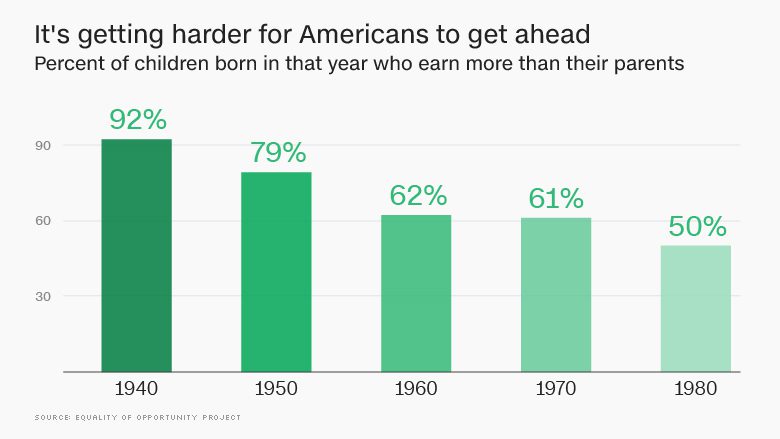

Whether America actually is exceptional is not the crux of the matter. Rather, the core question is how convincingly Americans can tell themselves that it is true, and then deploy this narrative globally to bolster a national agenda. Today, with ever-increasing speed and for a larger segment of its population, the exception no longer holds. Real, material living conditions no longer chart progress.

|

|

Source: http://money.cnn.com/2016/12/22/news/economy/us-inequality-worse/index.html

The trend lines leave little doubt. We find ourselves facing unprecedented inequality, stagnant quality of life, and decline of the middle class. Further, the material facts that may have mortally wounded the exceptionalism Americans are so fond of include the country’s inability to come to terms with its historic racism exposed through cellphone videos of the continued disproportionate violence perpetrated against Black people. The scope and character of the platform proffered by the Movement for Black Lives demonstrates that today’s activists recognize the complex interconnections between the ‘dream’ and material conditions, which today must be understood within a globalized context. They assert: “We see ourselves as part of the global Black family and we are aware of the different ways we are impacted or privileged as Black folk who exist in different parts of the world.” One of the core difficulties that mainstream politicians have had with the movement is that it does not fit into a single category or pose simple fixes. Instead, the movement issues a warning about American politics beyond any specific group’s demands: until we have a democratic dispensation that thinks politics holistically and social justice in a global context, we do not have a democracy for the present moment.

What voters realized in rejecting mainstream politics in last Presidential election (setting aside the vagaries of the electoral college, which itself has not changed over time so must also be read as a symptom rather than cause of the outcome) is that the political programs of the established parties and patterns of politicking are not addressing real problems facing the country on the domestic or the international front, and certainly not yet connecting the two.

***

The problem of what to do with contentious historical markers that no longer serve their purpose of fixing historical meaning is not, in truth, all that difficult. The most common arguments against change include the slippery slope (if we start with Lee, where does it end, with George Washington?), affront to national historical memory (taking them down is ahistorical), or censorship (the statue is art and art has the right to be offensive). These arguments can each be dealt with, as long as there is real willingness to explore thoughtful and creative responses. There are many examples from the US and globally of how this can be done.

The problem of what to do with contentious historical markers that no longer serve their purpose of fixing historical meaning is not, in truth, all that difficult. The most common arguments against change include the slippery slope (if we start with Lee, where does it end, with George Washington?), affront to national historical memory (taking them down is ahistorical), or censorship (the statue is art and art has the right to be offensive). These arguments can each be dealt with, as long as there is real willingness to explore thoughtful and creative responses. There are many examples from the US and globally of how this can be done.

In some places, statues have simply come down—sometimes with such popular support that crowds have swarmed and tugged until an old leader fell. In others, a conquering new regime knocked the old leaders down.

Other places have chosen to preserve and contextualize the past to allow a more complex historical account to be rendered visible. Along this vein, recall the transformation of former prisons or camps, for instance, that have been converted into memorial museums that narrate the experience from the perspective of the victims of abuse.

Entrance to the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. |

Villa Grimaldi Park for Peace, Peñalolén, Chile |

Robben Island Museum, Private Bag Robben Island, Cape Town |

Perhaps the most recognizable example of this is the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, a former killing center operated by the Nazi regime as an integral part of the Final Solution, the plan to annihilate the network of Jewish communities across the European continent. Today and since 1947, it has functioned as a museum—its grounds still dusted with ashes of the population it destroyed, visiting remains a haunting experience.

At these sites, history is preserved, but all around it the story incriminates not celebrates perpetrators of violence. In this way, memorial sites express fidelity to history, by incorporating the experiences of people who suffered within their walls. This is the path for memory to be presented in a fashion more inclusive, democratizing and multidirectional. The work of contextualizing existing structures requires social and political investment in a new discussion about history and narrative that thus results, but it can work. As others have noted, the same can be done for statues

What to do with old memorials and monuments also raises the question what would we want in their place?

The old-style monument of soaring, super human proportions has not faded from the scene, but the choice to mount these figures in most countries, where critique is possible, becomes cause for complaint rather than celebration. Among the places where it remains most practiced is North Korea, where, for instance, in 2012 the likeness of Kim Jong–il joined Kim il-sung, dwarfing visitors under 22 meter high statues.

The North Koreans have even been sanctioned on their statue exports, but not before they finished work in 2010 for Senegal’s ludicrous African Renaissance Monument, which soars 160 feet into the sky. One can ride an elevator to the tip of the hat and stare out at the baby’s face, or the woman’s exposed breast. Glaringly lit at night, the statue is visible from across the city. Situated in a neighborhood that suffers from insufficient electrical supply, towering over a moderate Muslim populace, the statue is cause for considerable offense.

The North Koreans have even been sanctioned on their statue exports, but not before they finished work in 2010 for Senegal’s ludicrous African Renaissance Monument, which soars 160 feet into the sky. One can ride an elevator to the tip of the hat and stare out at the baby’s face, or the woman’s exposed breast. Glaringly lit at night, the statue is visible from across the city. Situated in a neighborhood that suffers from insufficient electrical supply, towering over a moderate Muslim populace, the statue is cause for considerable offense.

Models exist that better prompt questioning and address historical complexities. On November 26, 2005, a flashy-golden statue of Bruce Lee striking a defensive posture appeared in the Bosnian city of Mostar. The statue was crafted by Croatian sculptor Ivan Fijolic. Vandalized in 2005, it was taken down shortly after its unveiling. It was re-mounted in the city park in 2013. Vesilin Gatalo of Mostar Urban Movement, who spearheaded the project, explained why a man known for his fictional exploits was an appropriate subject for tribute in post-war Bosnia. The monument, he stated, was dedicated to the idea “that justice, knowledge, honesty, good intentions can fight against corruption, evil, ignorance…”. He continued:

“…we have to show that we have many sub-identities; that we are not Muslims, Croats and Bosniacs. We are smokers, non-smokers. I don’t know. We are balding people, tall people, short people. And we have many other sub-identities, and one of that sub-identities is Bruce Lee. He is a hero from childhood of every one of us. Nobody will ask what kind of activities his people made during Second World War, First World War, in Turkish times[…] it makes him an ideal hero…”.

Reflecting disillusionment with the real-life leaders that the war and post–war environment offered them, Mostar Urban Movement wisely invested in a fictional embodiment of ideals that inspired them (a similar impulse was behind the mock-Presidential electoral bid of The Rock and Tom Hanks).

Memorials can also been seen as gifts for the future. In Nepal, families of the missing opted to create memorial chautara, a covered resting place engraved with the names of their disappeared loved ones. The structures would also serve as shelters for anyone who needed to rest and seek cover from the sun or rain – a place of comfort for a stranger, in the name of those whose final fate is unknown. As the brother of one missing man noted:

“This would give us solace in our heart and soul. People would remember him in days to come. Future generations will know that this was built in memory of that person. […] He was disappeared while working with the intention to contribute something to society, therefore, we want to build something in his name that commemorates his social nature.” (Robins 2104, 114).

***

When a community has engaged in the conversation about how to treat an old memorial or monument, and comes to a conclusion, even if it is not one that satisfies all, the democratic practice ought to be respected. Events this summer in Charlottesville, Virginia illustrate how horribly wrong is the decision to do otherwise. On August 12, 2017, a Confederate monument to Robert E. Lee provided the flashpoint for two irreconcilable views of the United States: one touted historical privilege and sought to assert its relevance to the present, the other countered with faith in the ideals of equality for the multi-ethnic, -confessional and -racial reality of today’s American population.

White nationalism has historic roots in history of the United States and appeals to a certain minority segment of the population: it is frightening and poses real risks to the political experiment that is American democracy. An extremely well-armed neo-Nazi and KKK rally descended on Charlottesville, Virginia, and ended when a white supremacist plowed his car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing Heather Heyer and wounding several others. The constant work of recalibrating ideals and policies required resolute response. Marking a low point in leadership, President Donald Trump failed to clearly condemn white supremacy, instead decrying the potential loss of “beautiful statues,” and equivocating with claims that there were “very fine people” on both sides.

Thus did the statue unveil the President.

Memorial logic is the precise opposite of the whim-driven superficiality of President Donald Trump’s version of politics. Responding to Charlottesville was a task that Trump, who reduces governance to momentary transactions, was distinctly ill equipped to manage. The time-horizon, vision, and questions about the country posed in the form of a Robert E. Lee monument are beyond Trump’s abilities.

Trump could bluster through a series of policy failures and scandals through truth-bending and egoist pronouncements, but was fated to crash against the metal and stone surface of a Confederate monument. It is not clear if Trump revealed himself as committed to the symbols of narratives of anti-Semitism and white nationalism–although he has full-heartedly built his base of support from these groups–or exposed himself as someone who by nature clings to vestiges of privilege as a value in and of itself. The difference may not matter, because the sum impact of his response to Charlottesville was Presidential embrace of the Confederate statues and encouragement to neo-Nazis and the KKK. But underneath his blatant support for these revolting allies, Trump has also revealed a particularly un-memorializable political moment, unhinged from anything resembling governance.

What this means for the country is determined less by Trump’s personal response then in how others viewed it. We have seen how white nationalist took it as encouragement, but elsewhere the responses to Charlottesville from within the American political, popular and corporate world suggest that America will again side with its narrative of freedom, equality and progress. The nation of diversity, the country has countered, will stay. We, the People, are not ready to abandon this storyline.

Let the Confederate statues fall; they have no place in the emerging story of America. The more troubling point for the country is that having someone who defends neo-Nazis and the KKK hold the position of President speaks to deep social, economic, and political woes, of which the man in the Oval Office is merely a symptom. The exceptional American story may survive the present, but the material conditions to build its future no longer exist. The challenge of narrating the future will require innovations of policy and community building across borders that, for the moment, is simply absent on the mainstream political stage. In the demise of Confederate statues today, we must also recognize that if today we were to build a statue to take their place, an effort inspired by the old dream of America, there would be no one on the pedestal.

If we have entered a period where memorials and monuments that are being newly mounted are less about ‘heroic’ individuals and more about ideas, humbled by histories of terrible violence and quietly instructing cautious vigilance for the future, this should be welcomed. We may need heroes and ideals, bold and eager for tomorrow, but we cannot change the fact that historical memory haunts. This is the truth of our moment; it cannot be ignored. Maybe at some day around the next corner of time, people will look back on today and mount a different sort of monument for the choices we have made.

The monuments of the future will not be built without holding true to at least some principles, even if they must adapt. How we respond to today’s memorial moments may well set the stage.

Notes

Robins, Simon. 2014. “Constructing Meaning from Disappearance: Local Memorialisation of the Missing in Nepal” International Journal of Conflict and Violence 8:1, 104-118.