On July 11, 2018, Jane Ferguson’s article, “Is intentional starvation the future of war?” appeared in The New Yorker. Included in it is a quote from Alex de Waal and our colleague, Wayne Jordash, from Global Rights Compliance. Below is an excerpt. The full piece is available through the New Yorker.

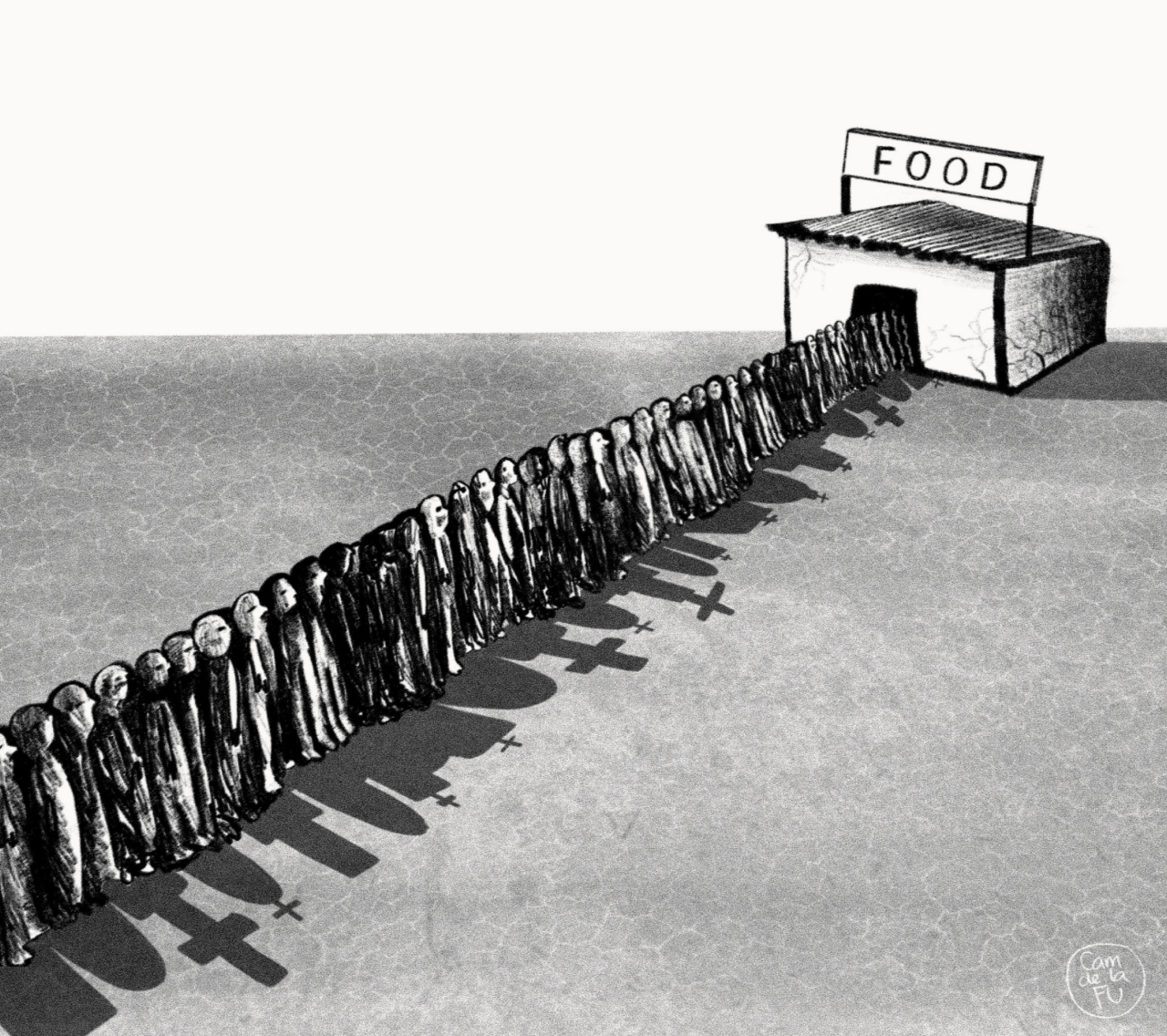

Human-rights groups question the legality of the Hodeidah offensive, as well as the Saudi-led blockade and aerial bombing campaign, on the grounds that they have created widespread hunger. The Geneva Conventions prohibit the destruction of “objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population.” Alex de Waal, the author of the book “Mass Starvation,” which analyzes recent man-made famines, argued that economic war is being waged in Yemen. “The focus on food supplies overall and humanitarian action is actually missing the bigger point,” de Waal told me. “It’s an economic war with famine as a consequence.”

Under international law, waging economic warfare is more of a gray area than the use of overt siege-and-starvation tactics. Stopping activities that are essential for people to feed themselves, such as closing off businesses and work opportunities, is not explicitly covered. “That is a weakness in the law,” said de Waal, who is also the executive director of the World Peace Foundation. “The coalition air strikes are not killing civilians in large numbers but they might be destroying the market and that kills many, many more people.”

The world’s most recent man-made famine was in South Sudan, last year. There, the use of food as a weapon was clearer, with civilians affiliated with certain tribes driven from their homes—and food sources—by soldiers and rebels determined to terrify them into never coming back. In the epicenter of the famine, starving South Sudanese families told stories of mass murder and rape. Entire communities fled into nearby swamps and thousands starved to death or drowned. Gunmen burned markets to the ground, stole food, and killed civilians who were sneaking out of the swamps to find food.

In Syria, the images of starving children in rebel-controlled Eastern Ghouta, at the end of last year, were the latest evidence of the Assad regime’s use of siege-and-starvation tactics. With the support of Russia and Iran, the Syrian government has starved civilian enclaves as a way to pressure them to surrender. In Yemen, none of the warring parties seem to be systematically withholding food from civilians. Instead, the war is making it impossible for most civilians to earn the money they need buy food—and exposing a loophole in international law. There is no national-food-availability crisis in Yemen, but a massive economic one.

The situation in Yemen goes to the heart of the major legal dispute regarding economic warfare: intent. Military and political figures can claim that they never intended to starve a population, and argue that hunger is an unintended side-effect of war for which they do not bear legal responsibility.

Despite this, some human-rights lawyers argue that a case can be made against the kinds of economic warfare being waged in Yemen. All of the parties are aware of the human impact of their tactics; continued refusal to modify them, despite warning of a famine, could leave some culpable. “If you move from negligence to recklessness and you continue with recklessness in the knowledge of the impact it’s having on the civilian population, eventually a judge will be able to see intent on your part,” Wayne Jordash, the head of Global Rights Compliance, a Hague-based human-rights group that monitors violations of the laws of war, told me.

The issue of legal culpability could extend to Washington, D.C. The Obama and Trump Administrations have provided support for the Saudi-led coalition since it intervened in Yemen. Since 2015, U.S. forces have refuelled coalition jets between bombing raids and provided intelligence assistance and logistical support. Washington has also sold Saudi Arabia and their ally the United Arab Emirates billions of dollars’ worth of weapons.

As weddings, markets, and civilian homes have been bombed, and the U.N. has verified that more than six thousand civilians have died, a growing bipartisan campaign to end U.S. military involvement in Yemen has grown in Congress. In a rare bipartisan push in the Senate, a resolution that would have ended all U.S. military support for the war in Yemen was narrowly defeated in March.

Human-rights groups say that if intent can be proven, some types of Saudi-led air strikes may be found to have violated the Geneva Conventions, because they make it difficult for Yemenis to access food. Along the Western coastline of rebel-held areas, Saudi-led air strikes often target fishing boats that pilots apparently—and, most likely, falsely—believe could be smuggling weapons to the Houthis from Iran. More than two hundred boats have been destroyed, and fishing communities suffer high levels of malnutrition and starvation.

Saada, the Houthis’ ancestral home and stronghold in the country’s northwest, has been pummelled by air strikes. Refugees from that area, who moved into makeshift camps near the border with Saudi Arabia after the strikes, told me that coalition forces then bombed their settlements. A man named Jabr Ali Al Ghaferi said that his wife was hit with shrapnel and died a few days later. “The air strikes targeted the gate and the bridge which connected the camp to the market,” he said.

Martha Mundy, a retired professor of anthropology from the London School of Economics, has, along with Yemeni colleagues, analyzed the location of air strikes throughout the war. She said their records show that civilian areas and food supplies are being intentionally targeted. “If one looks at certain areas where they say the Houthis are strong, particularly Saada, then it can be said that they are trying to disrupt rural life—and that really verges on scorched earth,” Mundy told me. “In Saada, they hit the popular, rural weekly markets time and again. It’s very systematic targeting of that.”

The Houthis add to the humanitarian challenges by making it difficult for aid agencies to work in the areas that they control. Mistrust of foreign aid organizations, particularly Western ones, has strained relationships. Aid workers who asked not to be named said that the Houthis have imposed increased restrictions on their operations in recent months. To enter Houthi-controlled areas, workers need special visas from Houthi officials, which are becoming increasingly difficult to obtain. After they arrive, they need permission to leave the capital and travel to refugee camps. “Every day they have different requirements,” a staff member ofone international aid group complained.

Aid agencies also complain about how the Houthis allow aid to be distributed. At least one major aid organization had to cancel a project after the Houthis said that they did not believe it was necessary and declined to grant permits. A second major aid organization said that the Houthis tried to gain control over the distribution of food and decide themselves who gets what.