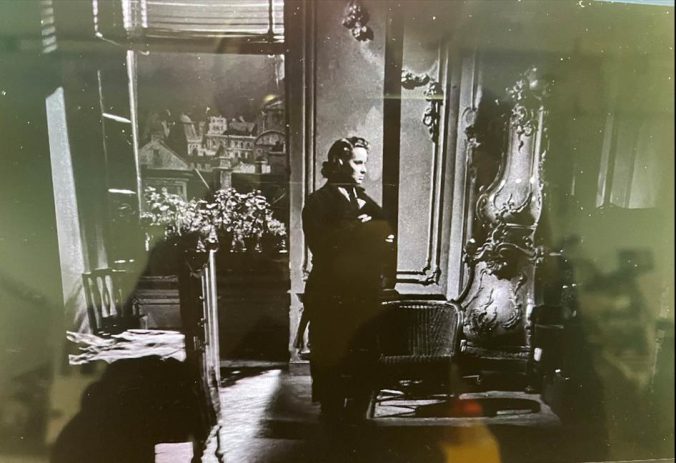

For this week’s discussion post, I was intrigued by the mention of a dream-like state, or the unconscious versus the conscious within the film. Notably, it was this scene at 1:07:00 in which Mike Vargas confronts Hank Quinlan and other American policemen on Quinlan’s planting evidence and dynamite.

I wanted to point out the framing of this shot, as Quinlan and Chief Gould stand between Vargas and Adair. Vargas and Adair are standing in the foreground with Quinlan and Gould in the background. The characters move back and forth from the foreground to the background- the three American policemen move from behind the camera, argue in foreground then stand in wait in the background. On the other hand, Vargas comes from behind the camera, argues with Adair in the foreground, but then exits to the left, never entering the background. The emptiness of the foyer, which lacks furniture and has distinct geometric architecture, and the echoing of the argument that enhances this ‘dream-like’ effect. Furthermore, Vargas and Adair are slightly offset, as Vargas is a little further from the camera (as seen by their feet), reiterating an unsettling effect due to the lack of symmetry. While Quinlan and Gould’s shadows are distinct and sharply defined, Vargas’ shadow is distorted by the bend in the ceiling and from the light diffusion from Vargas’ right side. This makes Vargas seem the most ‘dream-like,’ or unconscious of the four characters in the scene.

With these details in mind, Welles’ intention with the scene is to not only capture Adair and Vargas’ argument, but includes Quinlan and Gould standing between them and showcases the emptiness of the room they are in. The scene emphasizes the differences between American and Mexican police forces as they are in the movie. Namely, it is Vargas’ desire for justice and his morality that contrasts with Quinlan’s ego, reputation, and corruption.

The scene also relates to the racial divide between the two countries and the characters’ perception of race. Adair demands Vargas to kneel and apologize to Quinlan and Gould, attempting to belittle and undermine him. Of course, Adair’s command stems his position of power as a white man near the Mexican American border and highlights conflicts between white Americans and Mexican people.