Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

While it is largely acknowledged that mass atrocities occurred in Uganda after Milton Obote was overthrown by Idi Amin and throughout Amin’s rule, less well-known is the continuation of mass atrocities after Obote was returned to power following a Tanzanian invasion. The mass atrocities committed in Uganda both during the presidency of Idi Amin and the second presidency of Milton Obote have roots in the latter’s first term in power. Obote was independent Uganda’s first prime minister and he quickly took steps to consolidate his power, naming himself president and declaring a state of emergency that allowed him to rule with impunity. His regime was marked by corruption and nepotism—particularly towards the ethnic groups most loyal to him: the Langi and Acholi. General Idi Amin led a coup against Obote on January 25, 1971, thus beginning his bloody military regime. Amin began by killing ethnic groups most loyal to Obote, but by the time he himself was overthrown in 1979, almost every ethnic group in Uganda had been a target of his purges. Obote returned from exile with the support of the Tanzanian military, and he regained the presidency in the 1980 elections. But Uganda’s violence did not end. An insurgency led by Yoweri Museveni and the National Resistance Army (NRA) violently contested the elections and Obote’s army responded with a brutal counter-insurgency, which became known as the Ugandan Bush War.

We have not included violence related to the Lord’s Resistance Army (1989 – present), as perpetrated by either the LRA or the government forces, because while the cumulative number of civilians killed is estimated at 63,826-99,941,[i] we cannot establish credible annual figures as to enable us to ensure that the violence fits within the time thresholds that govern this project. Documentation of LRA crimes is exceptionally poor throughout the period when the LRA was most active in Uganda, 1989 – mid-2000s.

Atrocities

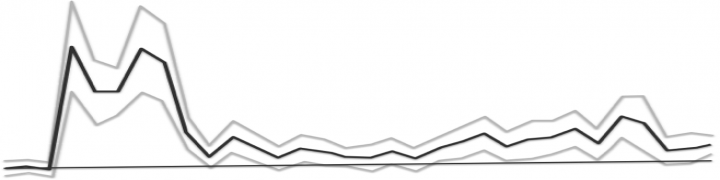

It is very difficult to separate patterns of violence against civilians from the general conduct of the civil war (1980-1986) that began within one year of Obote’s return to power. The war pitted Uganda’s government under Milton Obote (the Uganda People’s Congress or UPC) against Yoweri Museveni’s rebel forces, the National Resistance Army (NRA). Both sides of the guerilla war committed mass atrocities against civilians and the instability also produced massive displacement. Civilians were targeted based on their perceived political allegiance, which often was treated as synonymous with ethnicity. In contrast to the reign of Idi Amin in which spikes of violence were associated with threats, both real and perceived, the second presidency of Obote was characterized by sustained violence.[xvii]

Obote’s UNLA forcers were primarily made up of Acholi and Langi soldiers. His forces were poorly trained, undisciplined, and committed the same sort of acts that were committed against them under the rule of Idi Amin.[xviii] Museveni’s NRA also targeted civilians in order to discredit Obote and confuse the population by dressing in UNLA garb. As Museveni intended,[xix] this created even more confusion as to which side was conducting the killings.[xx]

By February of 1981, Museveni had established his militia in the bush of the Luweero District.[xxi] He immediately began to target people perceived as loyal to Obote; displacing thousands. At this point, Obote tried to improve his soldiers’ treatment of civilians[xxii] and on May 27, 1982 Obote issued an order that the military stop harassing civilians and pillaging.[xxiii]

While the entirety of the second Obote regime was brutal, the events of January 1983 marked a key escalation in the targeting of civilians. Obote launched what came to be known as Operation Bonanza in the Luweero Triangle. UNLA soldiers ransacked settlements and farms. This is the major spike in violence during Obote’s second presidency and it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of people died or were displaced during this campaign.[xxiv] By the December of 1983, most of the fighting in the Luweero District was over.[xxv] However, in January of 1984, thirty women and children were killed by rebels in Muduuma, a village near Kampala.[xxvi] Rebels continued to commit acts of terrorism in and around Kampala into the summer of 1984.[xxvii]

Milton Obote could not control all aspects of his security forces. There was “open communal conflict” within his military, and soldiers of Acholi descent frequently committed insubordination against their superiors. Rifts in the armed forces were widened further by competition between different ethnic factions for control of weapons and supplies. Museveni was able to exploit this fracturing by capitalizing on the unified front of the NRA. As UNLA soldiers lost their will to fight for Obote, many chose to defect to the NRA, further weakening Obote. UNLA Lietenant General Basilio Olara-Okello, who was an Acholi, seized on this loss of support and overthrew Obote on July 27, 1985.[xxviii]

Fatalities

In the Amnesty International 1985 report, the organization cites an estimate made by the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs that between 100,000 and 200,000 people died.[xxix] The 1992 Library of Congress country study on Uganda states that estimates for how many people died between 1981 and 1985 is as high as 500,000 people.[xxx]

Endings

Thanks largely to the influence of Museveni and the NRA, public favor came to turn against Obote, who was overthrown in a coup d’etat led by Basilio Olara-Okello on July 27, 1985. The contradictions and infighting of Obote’s regime tore it apart internally.[xxxi] The violence declined even more significantly a few months later in January 1986 when Museveni’s NRA claimed control of the country.

Coding

We code this case as ending through military defeat of the government by insurgents, the NRA. We further note that there were multiple victims group across the span of the period of atrocities.

Works Cited

Amnesty International. 1979. Amnesty International Report, 1979. London: Amnesty International Publications.

Amnesty International. 1985. Amnesty International Report, 1985. London: Amnesty International Publications.

Avirgan, Tony, and Martha Honey. 1982. War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Westport, CT: L. Hill.

Decalo, Samuel. 1989. Psychoses of Power: African Personal Dictatorships. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Human Rights Watch. 1999. Hostile to Democracy: The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Ingham, Keneth. 1994. “Obote : a political biography,” London; New York: Routledge.

International Commission of Jurists. 1977. Uganda and Human Rights: Reports to the UN Commission on Human Rights. Geneva: Commission.

Kasozi, Abdu. 1994. The Social Origins of Violence in Uganda, 1964-1985, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Keatley, Patrick. 2003. “Idi Amin.” The Guardian, accessed November 14, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/ news/2003/aug/18/guardianobituaries.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 1984. Imperialism and Fascism in Uganda. Trenton, NJ: Africa World of the Africa Research & Publications Project,

Mazurana, Dyan and Anastasia Marshak, Jimmy Hilton Opio, Rachel Gordon and Teddy Atim. 2014. “The Impact of serious crimes during the war on households today in Northern Uganda.” Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium, Briefing Paper 5, May. Available at: http://www.securelivelihoods.org/publications_details.aspx?resourceid=298 Accessed January 12, 2017.

Mutengesa, Sabiiti. 2006. “From Pearl to Pariah: The Origin, Unfolding and Termination of State-Inspired Genocidal Persecution in Uganda, 1980-85.” How Genocides End, accessed December 6, 2013, http://howgenocidesend.ssrc.org/Mutengesa/

Ofcansky, Thomas P. 1996. Uganda: Tarnished Pearl of Africa. Boulder, CO: Westview.

United States Library of Congress. 1992. “Library of Congress Country Studies: Uganda,” Washington, D.C. : Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Accessed 1 Dec. 2013, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/ugtoc.html.

Waugh, Colin. 2004. Paul Kagame and Rwanda: Power, Genocide and the Rwandan Patriotic Front. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co.

Notes

[i] Mazurana et al 2014.

[xvii] Kasozi 1994.

[xviii] United States Library of Congress 1992.

[xix] Ingham 1994., 178.

[xx] Ibid., 179.

[xxi] Note, amongst Museveni’s forces were some Rwandans displaced into Uganda from periods of violence in their home country. Among them were Paul Kagame, who would later lead the Rwandan Patriotic Front and become President of Rwanda, and Fred Rwigyema (Waugh 2004, 40).

[xxii] Ibid., 186.

[xxiii] Ibid., 187.

[xxiv] Ofcansky 1996, 54.

[xxv] Ingham 1994, 197.

[xxvi] Ibid., 200.

[xxvii] Ibid., 202.

[xxviii] Mutengesa 2006.

[xxix] Amnesty International Report, 1985. London: Amnesty International Publications, 1985. Print, 108.

[xxx] United States Library of Congress 1992.

[xxxi] Mutengesa 2006.