Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

The population of Sri Lanka is composed of approximately 73.8% Sinhalese (Buddhist), 12.7 and 5.1% Sri Lankan Tamil and Tamils of Indian origins (Hindu), respectively, who are concentrated in the north, and 8% Sri Lankan Moors, in addition to other smaller groups.[i] The country gained its independence from Great Britain in 1948. The first post-independence government included representatives of both the Sinhalese and Tamil communities. In 1956, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike was elected prime minister, advocating policies that favored the Sinhalese and opposed efforts by Tamil to allow for regional autonomy and recognition of their linguistic, cultural and political claims. The opposition began a series of nonviolent protests and efforts to politically resolve the situation, resulting in a new pact, but Buddhist extremists assassinated Bandaranaike. The next decades witnessed coup d’état attempts, a brief Marxist insurgency, and policies that discriminated against the Tamil. According to the UN Panel of Experts, the government encouraged and at times supported anti-Tamil attacks, notably in 1977, 1979, 1981, and 1983. The 1983 anti-Tamil riots led to the emergence of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), who conducted low-level insurgency and demanded independence. Their attacks on government targets were followed by additional anti-Tamil pogroms.[ii]

The conflict escalated in 1986 – 1987, with Sri Lankan forces—supported by military advisors from Pakistan, Singapore, Israel, and South Africa—targeting the northern city of Jaffna amidst reports of high civilian casualties, prompting India to increase its role in the conflict. India had provided limited military and other support to the LTTE, and its interests arose from both concerns for its regional economic and political power, and in response to pressure from its own Tamil population. In 1987, India pursued negotiations with Sri Lanka, resulting in the Indo-Sri Lankan Accord, which brought the two countries’ governments closer and subsequently deployed the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF).

However, as the IPKF attempted to carrying out its tasks of disarming and later going on the offensive against the LTTE, it lost favor with the Tamil, even as Sinhalese leaders resented its presence on their territory. In 1990, the IPKF withdrew and the conflict between the LTTE and Sri Lankan government resumed. That same year the LTTE purged Muslims and massacred Sinhalese and Muslim civilians in villages along the borders of its areas of control. An LTTE suicide bomber killed Indian former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991 and Sri Lankan President Ranasinghe Premadassa in 1993.

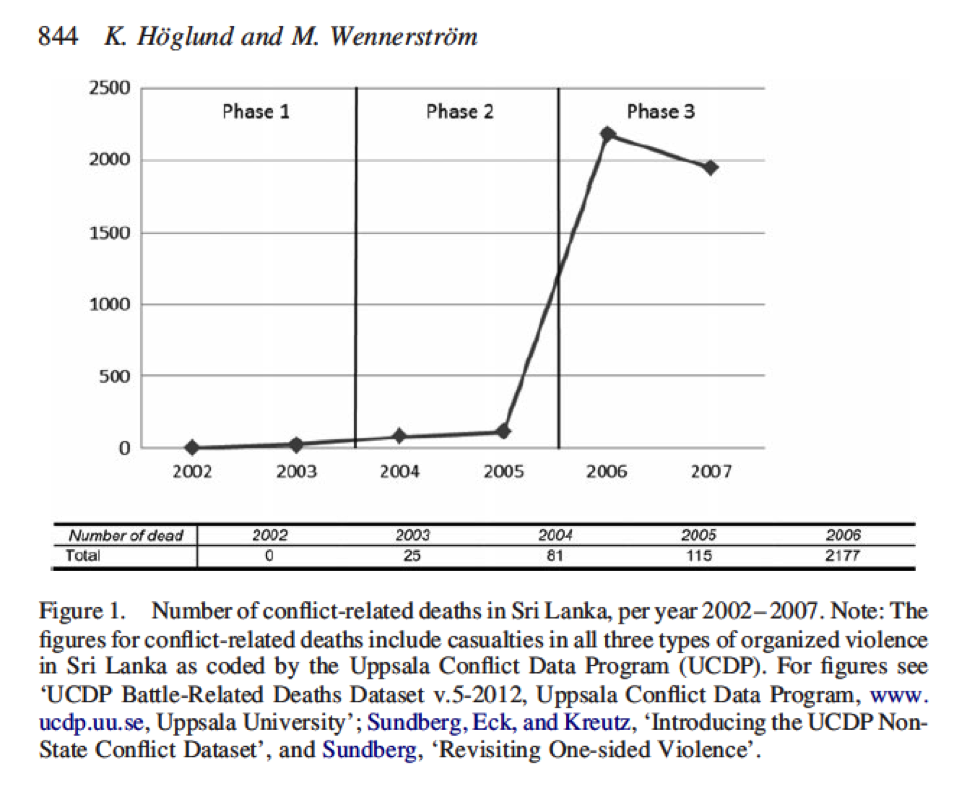

Throughout the conflict, beginning in 1985, multiple mediation efforts were undertaken. Initially by India (1985), directly between the government and LTTE leaders in 1989 – 1990 and in 1994 – 1995, and by the Norwegian government in 2000 – 2002. The LTTE launched a major offensive in 1999 – 2001,[iii] after which point a Norwegian mediated ceasefire took hold, monitored by the Scandinavian–staffed Sri Lankan Monitoring Mission (SLMM)[iv]. However, citing lapses in the government’s commitment to key political reforms, the LTTE again launched attacks beginning in 2003.

Throughout, the LTTE presented itself as the only voice of the Tamil, using harsh repression against any internal opposition.[v] In areas it controlled, the LTTE “monopolised politics, leadership, institutions and much of society in general,” and used the suffering of its people to mobilise support from the Tamil diaspora.[vi] Additionally, the LTTE used forced conscription, including child soldiers, and taxed the population. Their approach eventually caused an internal rift in 2004, weakening the group as the commander of its eastern wing, Karuna Amman, defected with thousands of followers to the government side.[vii] Based on the LTTE’s history of using truck bombs, suicide bombers and targeting civilians, the group was declared a terrorist organization by the US in October 1997, and the EU in May 2006. This designation led to the withdrawal of EU monitors from the SLMM, further isolated and drew the ire of the LTTE. Fighting resumed in 2006 and the government officially abandoned the ceasefire in 2008.

Atrocities

Uyangoda argues that as the Sri Lankan government, since 2005 led by a Sinhalese nationalist coalition, considered its options, it believed that it could decisively defeat the LTTE, if military leaders could be freed from interference by political leaders and any human rights considerations. This perception ushered in a “clear division of labor between the civilian and military leadership…while the military establishment was given a freehand in planning, strategizing, and executing the war, the political leadership managed its political front domestically, regionally and internationally.”[viii] It embarked on a campaign to win international favor by framing its offensive in line with the ‘Global War on Terror,’ appointed new leaders within the military and government who would increase cohesion, and tripled the size of its military force.[ix]

The defection of the LTTE commander of the eastern province in January 2008, paved the way for the government’s strategy of concentrating the remaining Tamil population and LTTE into an ever-reduced geography, where government forces could deploy heavy weaponry against them. Additionally, the government used special units to dismantle the LTTE’s networks across the country, eliminating people believed to be associated with the group.

The final push culminated with the government’s concentration of the LTTE and an estimated 330,000 civilians from the population of Vanni into an ever-decreasing area.[x] The government fired into “No Fire Zones” where it had encouraged the population to concentrate; on the UN hub where food and aid were being distributed, near ICRC ships picking up the wounded, and directly targeted hospitals.[xi]

The LTTE’s numbers were estimated in September 2008 at 20,000, and by the final stages of the war were suspected to have fallen to 5,000.[xii] They exposed the population under its control to further violence by restricting their ability to flee the government onslaught, deploying weaponry near or in civilian sites, and by using civilians as a human buffer against government forces. The UN Panel of Experts reports that the LTTE shot point blank at civilians attempting to flee its areas from February 2009 until the end of conflict

After the conflict ended, the government committed further abuses against the surviving Tamil population: housing them in massively overcrowded camps, screening suspected Tamil without transparency, torturing and summarily executing some suspected LTTE members, raping women and obstructing the delivery of aid. Decreasing the capacity of outside organizations to document civilian fatalities and purposefully misstating the number of displaced and killed people was part of the government’s campaign. The government’s enormously inaccurate estimates of the IDPs—for example, stating there were 10,000 when the UN estimated 127,177 trapped at the end of April–led to the delivery of a fraction of the supplies required to tend to the population.

Timeline of key events in the final offensive Unless otherwise noted, this timeline draws on the narrative produced in the UNIRP 2012.

Late summer 2008: The SLA approached LTTE headquarters in Kilinochchi, which was also the UN headquarters.

8 Sept 2008: The government announced it cannot guarantee safety of internationals in the Vanni. The UN headquarters moved to Vavuniya outside the conflict zone, with around 320 INGOs and national staff staying.

October 4 – November 21: Ten UN convoys with humanitarian supplies entered area.[xiii]

2 January 2009: The government advanced and captured Kilinochchi; it encouraged the LTTE to surrender.

16 January: The eleventh and last UN humanitarian convoy entered the Wanni.

20 January: The government declared ‘No Fire Zones’ (NFZ) and began a push to capture Puthukkudiyiruppu (PTK area, outside of the NFZ).

21 January: Most UN staff left the PTK area for Vavuniya, but the LTTE refused to allow nationals to leave. Two UN representatives decided to stay. The government declared a 35-square kilometer area to be a ‘safe zone’ for civilians, dropped fliers telling civilians to go there, and then repeatedly fired shells into the area. As a UN report noted: “two –thirds of civilians injured and killed…were…in the safe zones.”[xiv]

19 – 24 January 2009: SLA fired repeatedly into the NFZ.

29 January 2009: The two remaining UN staff left, and the LTTE refused to let them evacuate the 86 dependents of their 17 national staff, many of whom then opted to stay with their families.[xv]

February: The LTTE commenced a policy of shooting civilians attempting to flee.

February: According to UN Internal Review Panel, not until this month did the UN have any systematic capacity to record fatalities, the COG was created and used a standard of three sources to verify deaths.[xvi]

4 February: The SLA shelled a hospital in PTK, a strategic stronghold for the LTTE.

6 February: The SLA shelled continuously within NFZ area; where estimates suggest between 300,000 and 330,000 civilians had sought safety.

Feb – May: The SLA shelled other hospitals

February – May: The ICRC attempted evacuations and delivery of aid to besieged civilians by sea, but the government obstructed their effort. Nonetheless, it is estimated at 14,000 people were able to flee by sea.

Early April: The LTTE retreated to a coastal strip amidst heavy government shelling. Around 100,000 civilians fled, in addition to 70,000 who had already exited, leaving an estimated 130,000 civilians inside the war zone. The government claimed only 10,000 civilians remained. The LTTE increased its efforts to force them to stay in its areas of control and sent soldiers to certain death rather than surrender.

Early May: The LTTE leadership tried to negotiate surrender through the UN, but the government rejected a UN presence at a surrender site.[xvii]

13 – 18 May: “Shells rained down everywhere and bullets whizzed through the air. Many died and were buried under their bunkers or shelters, without their deaths being recorded.”[xviii]

16 – 19 May: The surviving civilians made their way out of the war zone, where the dead and wounded lay everywhere.

18 May 2009: The LTTE leadership and their dependents (estimated to be a group of 300 persons) were in regular touch with international actors (UN, Norway, US, UK, ICRC among others[xix] to try to negotiate surrender. The government instructed them to walk out slowly under a white flag, which they did. Shortly afterwards, the BBC and other media reported that the group had been shot dead.

19 May: The government showed bodies of the dead LTTE leaders: Charles Anthony, Nadesan, and Pulidevan.

May – June 2009: IDPs in government run camps reached a peak of 282,000, with some 250,000 in Menik Farm.[xx]

22 January 2010: Roughly 160,000 IDPs returned to their homes since August and by November 2010, according to the UN RC, 80% of the IDPs had returned.[xxi]

Fatalities

Civilians were killed in several ways during this final offensive: a small number were killed during the in targeting of the LTTE’s network across the country (outside the war zone); extensive killing of civilians caught within the ever-decreasing area of the war zone, largely by government shelling, but also as the LTTE used them as shields; and in the IDPs camps at various stages during the conflict and after it ended. The numbers here, as in most cases, are hotly disputed.

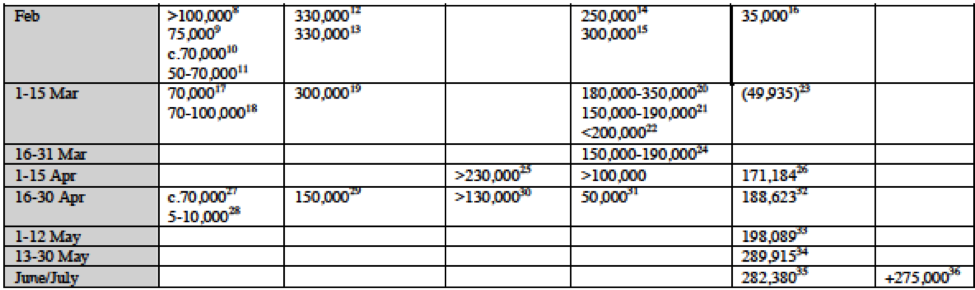

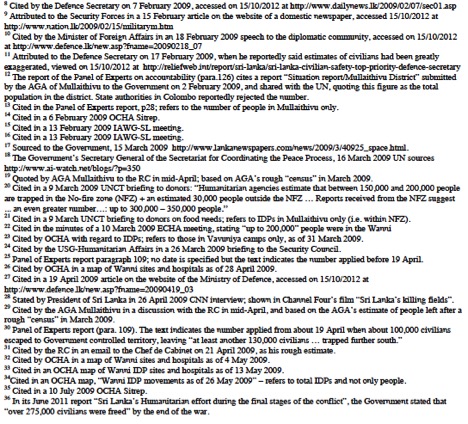

The below chart, while not at all comprehensive in terms of the total number of civilian deaths, gives an indication of the rapid escalation of killing during this final period.

The UN Panel reviewing the conflict cites multiple reasons why the given estimates of the dead are not authoritative:

- Number of people in the conflict zone is contested. The UN suggests it was as high as 330,000;

- Lack of an accurate count of those who fled Vanni, due to government’s lack of transparency;

- Lack of certainty regarding the number of LTTE combatants, complicated by their use of forced conscription and child soldiers;

- The fact that many civilians were buried where they fell, their deaths never registered.

To these difficulties, the UNIRP also adds that before the war the LTTE had an interest in inflating population figures, as the number directly related to their ability to stake political claims and access humanitarian aid; there was considerable displacement throughout the period; there were wide ranges of numbers put forward, including from the government who revised their figures multiple times.[xxii]

Nonetheless, the UN Panel of Experts summarizes the best information about fatalities that they could find. They argue that 75,000 people were killed, based on subtracting those from the number of people thought to be in the zone (330,000) from those who were known to have fled the NFZ area (290,000), plus 35,000 from earlier period of the conflict.[xxiii] The UN Country Team was able to directly document 7,721 killed and 18,479 wounded from August 2008 – 13 May 2009. After this point, they no longer had access to information that met their standard of proof–verified across three sources — and they halted counting before the final push when the numbers likely increased exponentially.

Limited surveys in the post-conflict context (unspecified), citing “credible sources” estimate “up to 40,000” civilian deaths.[xxiv]A SRI Lankan NGO, the University Teachers for Human Rights, issued a report arguing that, measuring the numbers of IDPs against what was known about the size of the affected population, a minimum of 40,000 people went missing or died.[xxv] The UNIRP also cites a report submitted to the LLRC [SL Government sponsored report, ‘Lessons Learned and Reconciliation Commission’] by Government Agents in Killinochchi and Mullaithivu that puts forward a number of 46,679 people unaccounted for, based on population estimated at 429,059 in October 2008.[xxvi]

These numbers do not include deaths outside the conflict zone or after the end of the conflict during the ‘screening process’ or due to conditions inside the IDP camps. These camps were woefully inadequate to the needs of the population. Additionally, there were widespread reports of rape and sexual violence in the camps by government and government-affiliated forces.

As numbers reported in the UN IRP[xxvii] make clear (chart below) differences between the estimated size of the original population in the targeted area, versus the number of IDPs who emerged from the area, leave considerable questions about the total number of people killed.

Sources, as noted by the UN IRP 2012, Annex II, 38 – 39.

Endings:

The civilian fatalities ended finally with the government’s military defeat of the LTTE and the eventual release of most people from the IDPs camps (with significant numbers leaving August 2009 – Jan 2010), in addition to the easing of restrictions on those who remained. International protests may have impacted the decisions related to conditions in the camps. However, as the UN Independent Inquiry makes clear, the UN failed its responsibilities to protect civilians from the greatest harm during the conflict and the SL government was effective at silencing or sidelining non-governmental human rights actors, and had achieved sufficient cohesion amongst world powers in support of their offensive to avoid the scrutiny warranted by the level of violence they unleashed against civilians.

Coding

We code this case as ending ‘as planned’ by the primary perpetrators who were then able to normalize conditions. We also code for a nonstate actor, the LTTE, as a secondary perpetrator of violence against civilians.

Works Cited

Brun, Catherine and Nicholas Van Hear. 2012. “Between the local and the diasporic: the shifting centre of gravity in war-torn Sri Lanka’s transnational politics”, Contemporary South Asia, 20:1, 61-75

Höglund, Kristin and Marcus Wennerström. 2015. “When the going gets tough…Monitoring Missions and a Changing Conflict Environment in Sri Lanka, 2002 – 2008.” Small Wars and Insurgencies 26:5, 836 – 860.

Uyangoda, J. 2015. “The LTTE and Tamil insurgency in Sri Lanka: political/cultural grievance, unsuccessful negotiations and organizational evolution” in Ethnic Subnationalist Insurgencies in South Asia: Identities, Interests and Challenges to State Authority, ed Jugdep S. Chima (London: Routledge, 2015),

United Nations Secretary General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka (UN PoE). 2011. “Report.” United Nations, 31 March. Available: http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/Sri_Lanka/POE_Report_Full.pdf Accessed January 13, 2017.

United Nations Secretary General’s Internal Review Panel on United Nations Action in Sri Lanka (UN IRP). 2012. “Report.” United Nations, November. Available at: http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/Sri_Lanka/The_Internal_Review_Panel_report_on_Sri_Lanka.pdf Accessed January 13, 2017.

University Teachers for Human Rights (JAFFNA). 2009. “Let Them Speak: Truth About Sri Lankas’ Victims of War.” Special Report No. 34, 13 December. Available at: http://www.uthr.org/SpecialReports/Special%20rep34/Special_Report_34%20Full.pdf Accessed January 13, 2017.

Notes

[i] Census of 1981, as cited by Uyangoda 2015, 102.

[ii] The 2011 UN Working Group on Disappearances ranked Sri Lanka as second-highest country in terms of disappearances, which continued into the 2000s although at lower rates (UNIRP 2012, Annex III, 42).

[iii] Uyangoda 2015, 111.

[iv] The SLMM formally ended only in 2008 with the return to full-fledged war. Höglund and Wennerström 2015, 838.

[v] Höglund and Wennerström 2015, 843.

[vi] Brun and Van Hear 2012, 65.

[vii] Uyangoda 2015, 118.

[viii] Uyangoda 2015, 115.

[ix] UN PoE 2011, 15.

[x] UNPoE 2011, ii.

[xi] UN PoE 2011, 11.

[xii] UN PoE 2011, 18.

[xiii] UNIRP 2012, Annex III, 53 – 56.

[xiv] UNIRP 2012, Annex III, 69.

[xv] UNIRP 2012, Annex III, 59.

[xvi] UNIRP 2012, 19.

[xvii] UNIRP 2012, 21.

[xviii] UN PoE, 2011, 35.

[xix] UN PoE 2011, 47 – 48.

[xx] UNIRP 2012, Annex III, 90.

[xxi] UNIRP 2012, Annex III, 91.

[xxii] UNIRP 2012, Annex II, 37.

[xxiii] UN PoE 2011, 40.

[xxiv] UN PoE 2011, 41.

[xxv] University Teachers for Human Rights (JAFFNA) 2009, 303.

[xxvi] UNIRP 2012, Annex II, 38.

[xxvii] UNIRP 2012, Annex II, 38 – 39.