U.S. Bombing & Civil War | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending

Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction: U.S. Bombing & Civil War

Between 1965 and 1973, the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia aggravated and radicalized internal Cambodian political disputes. These disputes readily became armed contests characterized by shifting alliances, regional struggles for dominance (including the US, Soviet Union, China and Vietnam), and Cambodian efforts to assert different varieties of militant nationalism (whether royalist, communist or otherwise). The result for civilians was devastating.

Atrocities 1965 – 1973

In 1965, Cambodia officially cut ties with the U.S., as Prince Sihanouk, the country’s head of state, tried, in his words, to maintain the country’s neutrality regarding the war in Vietnam. Nonetheless, his policies allowed Vietnamese communists to use border areas and the port of Sihanoukville. The U.S., under Lyndon Johnson’s administration, responded with targeted bombing of military installations and occasional attacks on Cambodian villages by South Vietnamese and American forces. Between 1965 and 1969, the U.S. bombed 83 sites in Cambodia. The pace of bombing increased in 1969, as U.S. B-52 carpet-bombing began, in support of the slow pullout of U.S. troops from Vietnam. Bombers targeted mobile headquarters of the South Vietnamese “Viet Cong” and the North Vietnamese Army in the Cambodian jungle.[i]

In March 1970, a coup was launched against Prince Sihanouk resulting in a new government with Lon Nol at the helm. The coup government made a drastic change in Cambodian policies, deciding to counter the North Vietnamese, in support of the South Vietnamese and U.S. forces. In May 1970, the US and South Vietnamese launched an offensive into Cambodia, with the aim of cutting off North Vietnamese supply routes. The Vietnamese Communists widened and intensified their actions in Cambodia as well, working with insurgent Cambodian communists.[ii] After the U.S. ground invasion failed to root out the Vietnamese communists, in December 1970, Nixon instructed his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to order the Air Force to ignore restrictions limiting U.S. attacks to within 30 miles of the Vietnamese border, expanding the bombing areas. However, extensive bombing forced the Vietnamese communists further west and deeper into Cambodia, and ultimately radicalized Cambodian citizens against the government

An alliance of royalist, Cambodian and regional communist forces fought against the Lon Nol government, US and South Vietnamese forces, and, despite many internal rifts, expanded their areas of control quickly. By 1971, writes Kiernan, the Lon Nol government was secure only in the towns and their outskirts.[iii] As the allied Communist forces gained control of territory, the Communist Party of Cambodia (CPK) attempted to win over the Khmer soldiers fighting with the Vietnamese and to expel the Vietnamese forces. In some places, this effort resulted in heavy fighting between ostensible allies.[iv] As peace talks began in Paris, the CPK adamantly refused to participate in a negotiated solution.[v]

The final phase of the U.S. bombing campaign, from January to August 1973, aimed to halt the rapid advance of the Khmer Rouge on Phnom Penh, in response, the U.S. military escalated air raids that spring and summer with an unprecedented B-52 bombardment campaign that focused on the heavily populated areas around Phnom Penh, but which affected almost the entire country. The sum effect was that while the take-over of Phnom Penh was delayed, hard-liners within the CPK were strengthened, the populace further turned against the Lon Nol government, and the Communists’ recruitment efforts were facilitated.[vi]

After the U.S. bombing campaign ended in 1973, the civil war continued with the Communist forces making steady progress, despite fighting within their ranks and between groups.

Fatalities

Our research indicted a rough low estimate of 250,000 people during this period.

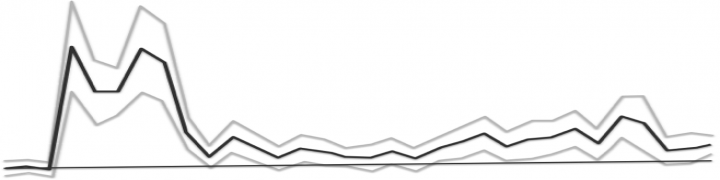

Fatalities from U.S. bombing were concentrated during the period in which U.S. President Richard Nixon’s administration carpet-bombed eastern Cambodia from 1969 to 1973, although bombings and incursions into Cambodia by the U.S. began in 1965 under President Lyndon B. Johnson and ended in 1975 under President Gerald Ford. More than 10 percent of the U.S. bombing was indiscriminate.

Former National Security Adviser than Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, an architect of US policy in Indochina, states in his book Ending the Vietnam War that the Historical Office of the U.S. Secretary of Defense gave him an estimate of 50,000 deaths in Cambodia due to the bombings from 1969-1973. The U.S. government released new information about the extent of the bombing campaign in 2000, leaving Owen and Kiernan to argue that the new evidence released by the U.S. government in 2000 support higher estimates.[vii] On the higher end of estimates, journalist Elizabeth Becker writes that “officially, more than half a million Cambodians died on the Lon Nol side of the war; another 600,000 were said to have died in the Khmer Rouge zones.”[viii] However, it is not clear how these numbers were calculated or whether they disaggregate civilian and soldier deaths. Others’ attempts to verify the numbers suggest a lower number. Demographer Patrick Heuveline[ix] has produced evidence suggesting a range of 150,000 to 300,000 violent deaths from 1970 to 1975.

In an article reviewing different sources about civilian deaths during the civil war, Bruce Sharp[x] argues that the total number is likely to be around 250,000 violent deaths. He argues that several factors support this range: 1) Interviews with survivors after the Khmer Rouge period who discussed when and how their family members were killed; 2) research by social scientists Steven Heder and May Ebihara, both of whom (separately) conducted extensive interviews with Cambodians; 3) adding information about the geography of conflict and variations in the intensity of the conflict; and 4) application of insights from documentation of the Vietnam War.

Sharp addresses some reasons why discrepancies may appear in various interview-based sources. First, there may be different perceptions about what is a “war-related” death that would inhibit assessment of increased mortality. Second, deaths calculated in relation to reporting by family members requires that a family member survive and bombs would have high clustering of mortality, potentially killing entire families. Third, the areas heavily targeted by the U.S. bombing campaign were subsequently heavily targeted by the Khmer Rouge, again, potentially leaving a gap in reporting if no family members survived.

Endings

US bombing of Cambodia came to a halt in August of 1973 when the US Congress legislated its conclusion, following the signing of a peace agreement between the US and North Vietnamese. The Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol armies continued to fight for two more years until 1975 when Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge.

On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh and declared Day Zero, ousting the military regime and emptying the cities. The defeat of Lon Nol forces precipitated an end to civil war deaths, but the beginning of the Khmer Rouge’s purge of perceived enemies. The civil war ended when the Khmer Rouge decisively won, an “end” that served only as prelude to a more intensive period of targeting civilians (detailed in a separate case study).

Coding

This case is coded as ending by strategic shift, when the U.S., under Congressional pressure, halted its bombing campaign. We note both international and domestic factors as influencing shift, given the importance of the peace agreement with Vietnam. In this case, the ending of the bombing campaign, noted as a withdrawal of international armed forces, was the most significant factor in the decline in civilian deaths. This case was immediately followed by a new one, during which the Khmer Rouge was the primary perpetrator.

Works Cited

Banister, Judith and Paige Johnson. 1993.”After the Nightmare: The Population of Cambodia,” in Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: The Khmer Rouge, the United Nations and the International Community, ed. Ben Kiernan. New Haven, CT: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies.

Becker, Elizabeth. 1986. When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution. New York: Public Affairs.

Chandler, David. 2008. A History of Cambodia, 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2008.

Etcheson Craig. 1984. The Rise and Demise of Democratic Kampuchea. Boulder, CO: Westview/Pinter.

Etcheson, Craig. 1999. “‘The Number’: Quantifying Crimes Against Humanity in Cambodia.” Mass Graves Study, Documentation Center of Cambodia.

Gottesman, Evan. 2003. After The Khmer Rouge: Inside the Politics of Nation Building. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Heuveline, Patrick. 1998. “’Between one ad three million’: Towards the demographic reconstruction of a decade of Cambodian history (1970 – 1979).” Population Studies 52: 49–65.

Hinton, Alexandar Laban. 2009. “Truth, Representation and the Politics of Memory after Genocide” in People of Virtue: Reconfiguring Religion, Power and Moral Order in Cambodia Today. ed. Alexandra Kent & David Chandler. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

Hinton, Alexandar Laban. 2005. Why did they Kill?: Cambodia in the Shadow of Genocide. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Kiernan, Ben. 1985. How Pol Pot Came to Power : A History of Communism in Kampuchea, 1930 – 1975. London: Verso.

Kiernan, Ben. 2008. The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79, 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kiernan,Ben. 2009. “The Cambodian Genocide” in Century of Genocide, ed. Samuel Totten and William Parsons. Third Edition. New York: Routledge, 340 – 373.

Owen, Taylor and Ben Kiernan. 2006. “Bombs over Cambodia. The Walrus, October 2006, 62 – 69.

“Report of the Research Committee on Pol Pot’s Genocidal Regime.” 1983. Phnom Penh, Cambodia, July 25. http://gsp.yale.edu/report-cambodian-genocide-program-1997-1999.

Sharp, Bruce. “Counting Hell” Available at: http://www.mekong.net/cambodia/deaths.htm Accessed May 26, 2015.

Sliwinski, Marek. 1995. Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: un analyse démographique. Paris: Editions L’Harmattan.

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. 1980. “Kampuchea: A Demographic Catastrophe.” Washington, DC, January 17.

Vickery, Michael. 1984. Cambodia 1975 – 1982. Boston, MA: South End Press.

Notes

[i] Owen and Kiernan 2006, 67.

[ii] Kiernan 1985, 305.

[iii] Kiernan 1985, 322.

[iv] Kiernan 1985, 342.

[v] Kiernan 1985, 343.

[vi] Etcheson. 1984, 119.

[vii] Owen and Kiernan 2006, 67.

[viii]Becker 1986, 170.

[ix] Heuveline 1998.

[x] Sharp.