Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

A former Portuguese colony, East Timor (now Timor-Leste) is located on the Eastern half of the island of Timor (the western half became a part of Indonesia immediately following independence). The 1974 revolution in Portugal signaled the end of Portuguese colonial power, and immediately thereafter in 1975, pro-independence party the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin), with the support of a majority of the former colonial Timorese army, defeated a coup attempt led by Indonesia-leaning party UDT. Indonesia began military attacks from across the border in West Timor. Fretilin unilaterally declared independence on 28 November 1975. Indonesia, citing concerns about Fretilin’s left-leaning politics, invaded on December 7, 1975.

Atrocities

The first days of the invasion were characterized by targeted executions of Fretilin leaders and their families, indiscriminate killing, rape, torture, public executions in the capital Dili and in small towns. Despite Indonesia’s superior military and naval strength of 15-20,000 troops, the Timorese army (estimated at 2,500 professional soldiers and around 7,000 trained civilians) managed to resist to the Indonesian efforts to subdue the area.

The Fretilin leadership fled to the interior with many civilians and prisoners from the parties that had collaborated with the Indonesian military (eventually conducted massacres of these prisoners). Generally, civilian populations (possibly as many as 300,000) were beyond the reach of the Indonesian military who controlled the capital and towns for most of 1976, eventually able to organize farming, basic health care and education. By this point, Fretilin decided on a strategy of semi guerrilla resistance by its armed wing Falintil, supported logistically by the civilian population in the ‘liberation zones’ established in the interior. The continued survival of Fretilin as a political and military force capable of preventing Indonesia from exercising control over the whole territory clearly reflected number of aspects of the movement’s strength and popularity as it was built up before December 1975. However, as attacks from Indonesian forces intensified and food supplies disrupted, civilian deaths from hunger, shelling and disease began to rise dramatically. Many civilians wanted to surrender but were prevented from doing so.

Indonesia launched a new military offensive, preceded by a substantial troop build-up and acquisition of new military equipment (including from US and UK). Employing aerial strafing/bombing and ground attacks, the military overpowered one Fretilin base after the other as well as systematically destroying livestock and food sources, forcing Fretilin and civilians further into the interior. With so many civilians to protect, Falintil was constrained from mounting effective counter-offensives. In late 1978, the last Fretilin stronghold at Mount Matebian fell; Fretilin changed policy and allowed civilians to surrender while Fretilin/Falintil continued its guerrilla warfare. The rest of Fretilin leaders and followers were pursued, captured and killed; by March 1979 the military operation was disbanded and the Indonesian military declared East Timor “pacified”. Between 300,000 and 400,000 displaced people came under Indonesian control between early 1977 and early 1979.

Fatalities

According to a study by the Commissao de Acolhimento, Verdade e Reconciliacao (CAVR) and Human Rights Data Group (HRDAG), drawing on more than 8000 victim-statements, a graveyard census, and retrospective Mortality Survey of 1,396 randomly selected household, a minimum conflict-related civilian death toll for East Timor in the period 1974-1999 is 102,800 (+/-12,000).[i]

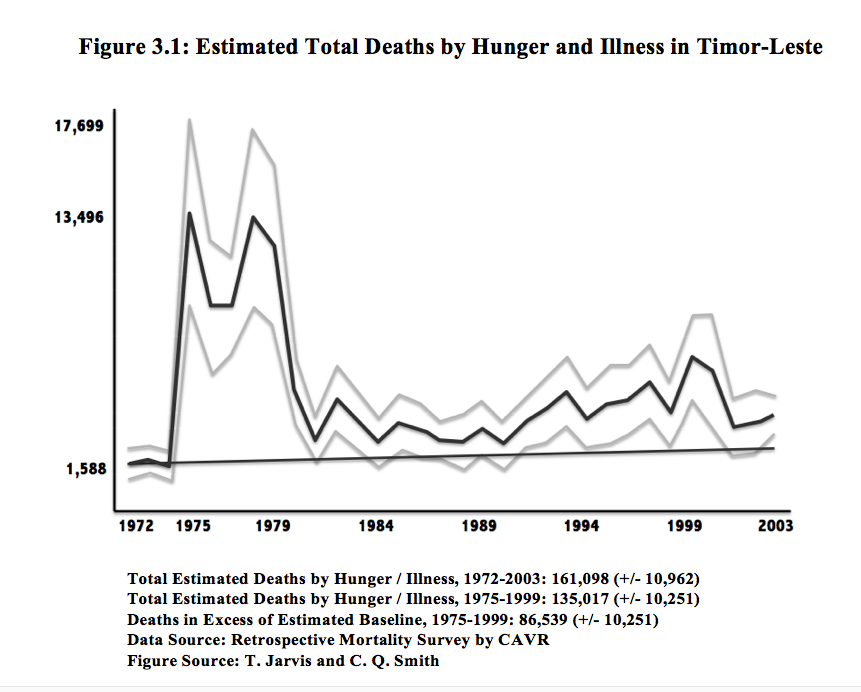

The estimate can be further broken down: (1) an estimate 18,600 total killings (+/-1000) using multiple systems estimation techniques and (ii) an estimate of 84,200 (+/- 11,000) deaths due to hunger and illness. The number of deaths attributed to “hunger or illness” rises to its highest levels during the immediate post-invasion period, 1975-1980. Whereas 1999 marked the high point for estimated killings 2,634 (+/-626). Significant for our study is not only the toll, but also its temporal concentration: CAVR/HRDAG chart an enormous spike in mortality between 1975 – 1980.[ii]

Figure from C.Q. Smith 2016, 90.

Robert Cribb a scholar who specializes on Indonesia, argues that a best estimate number (opposed to the above, which is best minimum) may place the figure for killing in East Timor between 1975 – 1980 around 50,000, although he also suggests a range of 30,000 – 80,000.[iii] Further, he argues that among the estimated 50,000 who died of malnutrition and disease wrought by the conditions of life, that a “significant portion of the rural population was shifted into strategic villages, in other words concentration camps where they could be isolated from Freitlin guerillas…”[iv] In December 1978, these camps held 268,644 or 318,921 persons in 15 different centers, under conditions that enabled the spread of disease, included forced labor, and limited food supplies.[v]

Endings

Significant incidents of killing occurred after 1980, including the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre of 271 protesting civilians. Nonetheless, we mark the decline of widespread killing and increased mortality as fits our study in 1980, given the range of data referenced above. Historical analysis suggests that the Indonesian military aimed to normalize the situation slightly earlier, in 1979.

Coding

We coded this ending as planned through a process of normalization.

Postscript

After many years of isolation from foreign visitors, a visit from then President Suharto “opened up” East Timor in 1988. The resistance re-mobilized and public acts of pro-independence (including during a visit by Pope John Paul II in 1989) internationalized the issue.

With the fall of Indonesian President Suharto after 31 years, the new Indonesian president B.J. Habibie allowed a referendum on East Timor’s status to take place in 1999. The ballot was marked intimidation and violence by Timorese militia widely believed to be organized by the Indonesian military, with estimated fatalities at least 2,000 deaths, the internal displacement of about 200,000 people and the destruction of 60-80% of private and public infrastructure. The violence ended as Indonesia’s new civilian leadership leveraged moderating control over the military—under considerable international pressure from allies the US and Australia, and from a UN mission on the ground—to end further repression and enable independence to move forward. An Australian peacekeeping force was subsequently sent to help stabilize the situation.

Works Cited

Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation (CAVR). 2005. “Conflict-Related Deaths in Timor-Leste 1974 – 1999” The Findings of the CAVR Report Chega!” Available at http://www.cavr-timorleste.org/updateFiles/english/CONFLICT-RELATED%20DEATHS.pdf

Cribb, Robert. 2001. “How Many Deaths?: Problems in Statistics of Massacre in Indonesia (1965 -1966) and East Timor (1975 – 1980), in Violence in Indonesia. ed ingrid Wessell and Georgia Wimhofer. Germany: Abera Verlag Markus Voss, 82 – 98,

Kiernan, Ben. 2003. “The Demography of Genocide in Southeast Asia: The death tolls in Cambodia, 1975 – 1979, and East Timor, 1975 – 1980” Critical Asian Studies 35:4, 585-597.

Smith, Claire Q. 2016. “Indonesia: Two similar civil wars, two different endings” in ed. Conley-Zilkic, Bridget. How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, The Sudans, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Klinken, Gerry .2012. “Death by deprivation in East Timor, 1975 – 1980” at http://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2012/04/17/death-by-deprivation-in-east-timor-1975-1980/ Accessed May 27, 2015.

Notes

[i] CAVR The report further notes that while the report includes 1975 conflict-related data, that data from this period “was not concise enough to make an explicit estimate about the civil war death toll” (2).

[ii] Van Klinken, 2012.

[iii] Cribb 2001, 94; and Kiernan 2003.

[iv] Cribb 2001, 89.

[v] Cribb, 89-90.