Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

The Vietnam War began in 1959-60, as an insurgency of Communist forces in South Vietnam, the Vietcong, against the government of South Vietnam. Although the United States supported the leadership of the South, advising President Ngo Dinh Diem as well as supplying military and financial aid, the scope of American involvement was relatively limited at this point. As the Southern government teetered towards on the verge of collapse, the U.S. intervened on its behalf, increasing its support over time, with massive commitment starting in 1965.

U.S. support changed fundamentally following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident (July 1964), where US military sources claimed they had been fired on by North Vietnamese torpedoes—claims later contradicted when previously classified materials were leaked to the public.[i] Prior to the Gulf of Tonkin, most civilian deaths were the result of attempts by governments in the North and South to consolidate power in a newly divided Vietnam.[ii]

In response to the alleged events in the Gulf of Tonkin, Congress gave a blank check to Pres. Johnson, allowing the administration to go on the offensive and “bring the war north.”[iii] The war involved regular armed forces of South Vietnam and the U.S. against the North Vietnamese Army and the Vietcong. American escalation included increasing the number of troops, mounting significant offensives and deploying large-scale aerial bombardment including use of napalm over both North and South Vietnam.[iv] This military activity led to an increased number of civilian deaths. Violence escalated between 1965 and 1975, peaked in 1968 and then decreased until 1973 when a cease-fire was signed between Hanoi and the United States. Civil war continued until 1975, when North Vietnam defeated the South, taking the capital Saigon in April 1975.

Atrocities

The war had few regular battles and no fixed front lines, but rather occurred in hundreds of small, geographically defuse actions designed to assert control of villages and their populations. Stathis Kalyvas and Matthew Kocher[v] argue that violence against civilians during the conflict was both selective (that is, targeted at the individual level) and indiscriminate (a result of widespread bombing or other attacks). They note that the Vietcong had established strong intelligence networks in the South and tended to target individuals, with the goal of “eliminating opponents and intimidating neutrals.”[vi] They further note that “while selective, Vietcong violence was also massive,” drawing on Lowy’s numbers to estimate that the Vietcong assassinated 36,725 persons.[vii]

The US and South Vietnamese bombing sorties, they note, tended to occur in Vietcong strongholds. On the ground, U.S. General Westmoreland pursued a war that sought to inflict as many casualties as possible on the DRV and Vietcong forces. As part of this strategy, American and ARVN forces carried out search and destroy missions in an effort to clear villages of guerilla fighters. As the name indicates, this was highly destructive policy with the sole goal to “find, fix, fight and destroy” enemy forces. While effective at clearing villages, the success was only temporary. Once American forces moved out, communist forces could easily reclaim the previously cleared village.[viii] Because these tactics seemed to be yielding high enemy deaths, Washington continued to support the war of attrition and statistics of enemy dead were accepted and reported to the public without much question.

United States Military Personnel in Vietnam[ix]

| 1965 | 184,000 |

| 1966 | 389,000 |

| 1967 | 463,000 |

| 1968 | 495,000 |

In addition to a dramatic increase in U.S. personnel and ground troops illustrated above, the United States began launching offensive air raids on North Vietnam.[x] The first of these air campaigns, Rolling Thunder, was waged between March 2, 1965 and October 31, 1968. The primary objectives of Rolling Thunder were to end the infiltration of men and supplies into South Vietnam and force Hanoi to peace negotiations.[xi] Military, industrial, and civilian targets were hit as Rolling Thunder moved further north. In an effort to maximize the destruction of the air war, American officials also lifted the restrictions on the type of weapons used in the air war. Beginning in the fall of 1965, the U.S. used napalm, white phosphorus and cluster bombs.[xii] Even with this unquestionable technological superiority, the United States was not making the progress it had been promising the public.

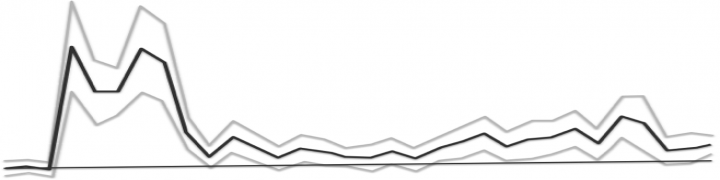

The disconnect between the reported success and actual progress of the war of attrition became painfully clear to the American public in January 1968 when communist forces launched a coordinated, national attack: the Tet Offensive. Since 1964 Americans had been promised a swift victory in Vietnam and the statistics from Westmoreland’s war of attrition had largely supported that premise. Yet, the Tet Offensive, despite resulting in heavy Vietcong casualties, illustrated that the Vietcong remained strong and able to coordinate a sophisticated, national attack.[xiii] In many ways the Tet Offensive signaled a turning point in America’s war in Vietnam, as 1968 and 1969 were the peak years of American in activity in Vietnam. In this two-year period, the U.S. had the largest number of troops on the ground. Furthermore, the data on civilian causalities illustrate that 1968 experienced the highest casualty rates.

Richard Nixon was elected in the fall 1968, in large part due to his promises of peace and the withdrawal of American forces from Vietnam. Efforts to meet this objective began in 1969 with the introduction of Vietnamization, in which ARVN forces would gradually take over ground military operations as American forces left the country. While the Nixon administration successfully began decreasing the number of troops, this should not be understood as a de-escalation of the war effort. Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger insisted that the war needed to be expanded before it could end and increased bombing of neighboring Cambodia and Laos.[xiv] Under this “madmen” policy, Nixon wanted to send 150,000 American ground forces into Cambodia, however, an increasingly hostile American public resulted in increased Congressional restrictions on troops involvement.

Nixon’s Vietnamization was demonstrated to be a failure in March 30, 1972 after a NLF tanks crossed the DMZ and easily swept by ARVN forces. In the face of the inability of ARVN to successfully deter NLF forces, coupled with increasing restrictions on American troop activity, the Nixon administration increased bombing of North Vietnam.[xv] Three different bombing campaigns followed in an effort to cripple the North’s effort and force them to the negotiating table. The first, Freedom Trail (April 1972), targeted civilian vulnerabilities and did little to coerce Hanoi. However, the next two campaigns were more successful. Linebacker I (5/1072) and Linebacker II (10/18/72-10/29/72) largely concentrated on Hanoi’s military capabilities and were important in reinvigorating peace talks between Hanoi and Washington.[xvi] Support for the conflict withered in the US as even positive momentum did not seem to create conditions for victory. A 1972 report by the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee noted, the war was not only “far from won, but far from over.”[xvii]

Fatalities: 1965-1975

The number of civilian deaths in the peak years of American involvement continues to be a highly contentious and politicized topic. To complicate matters further, reliable data is extremely difficult to find and scholars have often had to employ rather creative methods in order to calculate civilian deaths. It is therefore useful to outline some of the more important studies, before analyzing and coding the dynamics of violence in this period.

Charles Hirschman, Samuel Preston, and Vu Manh Loi’s “Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate.”

- “Absolute estimate” 1,050,000 war-related deaths, from 1965-1965

- 791,000 to 1,141,000 estimated war deaths between 1965-1975

- Midpoint of 966,000 +/- 175,000[xviii]

Hischman, Preston, and Loi’s impressive study represents one of the most creative and recent quantitative studies of Vietnamese deaths between 1965 and 1975. In a self-proclaimed “modern demography” the authors analyze the 1991 Vietnam Life History Survey (VLHS) to determine war-related mortality during the peak of violence. The VLHS was a small sample survey conducted in four representative locations in Vietnam that included questions regarding the survival status of parents and siblings, as well as the birthdates, year of death, and cause of death of parents and sibling.[xix] After evaluating the quality of the VLHS, Hirschman et al use the data to assess the American War’s impact on Vietnamese mortality.

“Estimates of Vietnamese war-related deaths, ages 15 and older, by age and sex, 1965-75”[xx]

|

Age & Sex |

All Deaths(1)

(Death rates per 1000)* |

Non-War deaths(2)

(Death rates per 1000) |

Ratio (3)

(3)=(2)/(1) |

Population 1970* (4) | Annual War Deaths (5) | Estimated Deaths

1965-1975 (6)=(5)x11 |

| Men | ||||||

| 15-29 | 10.9 | 1.5 | 7.11 | 4,681,000 | 43,861 | 482, 471 |

| 30-44 | 7.2 | 2.9 | 2.46 | 3,124,000 | 13,315 | 146, 469 |

| 45-59 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 1.17 | 2,234,000 | 2,410 | 26,510 |

| 60+ | 31.7 | 31.7 | 1.00 | 1,232,000 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 10.9 | 5.5 | 1.99 | 11,271,000 | 59,586 | 655, 440 |

| Women | ||||||

| 15-29 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.39 | 5,045,000 | 1,624 | 17,868 |

| 30-44 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 1.35 | 3,721,000 | 4,156 | 45, 718 |

| 45-59 | 8.8 | 6.8 | 1.29 | 2,376,000 | 4,755 | 52, 301 |

| 60+ | 36.1 | 34.6 | 1.04 | 1,600,000 | 2,471 | 27, 183 |

| Total | 6.4 | 5.4 | 1.19 | 12, 742,000 | 13,006 | 143, 070 |

*From the adjusted VLHS data on siblings and parents. **From United Nations 1994: 834

On the basis of the VLHS data, Hirschman and his team estimate that 655,000 men, 143,000 females, and 84,000 children were killed as a result of the American War for a total of 882,000 war deaths.[xxi] However, as the authors point out, this estimate is potentially low because the VLHS weighed urban and rural death rates equally. Vietnam’s population was 80 percent rural and 20 percent urban and when the data is adjusted for this, the number of war-deaths increases by 19 percent to give a total of 1,050,000. Using the range created by the differing weighing schemes, the authors add the standard deviation of 91,000, to give the final range of 791,000 to 1,141,000.[xxii]

For the purposes of this report, Hirschman’s study is useful because it provides a thorough demographic analysis of potential war deaths in the American War. Unlike many other studies of this period, Hirschman and his team are not concerned with the political motivations or impacts of American involvement in Vietnam. Instead, they offer a plausible estimate of the human cost of the war based on new sources and careful demography.

Unfortunately, their estimate does not differentiate civilian from military deaths, nor make any indication of how the death occurred (as a result of ARVN, US, or DRV action). However, it does offer a useful starting point for assessing Vietnamese loses in the peak years of their long war for independence.

Guenter Lewy’s America in Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

- 250,000 South Vietnamese civilian killed as a result of military operations

- 39,000 civilians “assassinated” by communist forces

- 65,000 North Vietnamese civilians killed by American bombing[xxiii]

Lewy’s book represents one of the earliest scholarly efforts to account for the number of Vietnamese killed during American military action in Vietnam. Published in 1978, Lewy’s estimates are largely based on figures provided by the U.S. Department Defense and have been increasingly questioned as new data comes to light. For instance, the figure of 65,000 North Vietnamese civilians killed by American bombings between 1965 and 1975 is based on the U.S. National Security Council estimate that 52,000 North Vietnamese civilians were killed as a result of American airstrikes form 1965-1969.[xxiv] Although American airstrikes continued, especially in the South, after 1969 they tended to occur further away from population centers and hit regions in Cambodia and Laos with greater frequency, making it extremely difficult if not impossible to determine an accurate number of Vietnamese killed as a result.[xxv] Because many of the figures Lewy provides are extrapolations based on estimates from American officials and government councils, one must keep in mind that he was working with incomplete data.

That being said, Lewy’s estimate of 1.2 million total Vietnamese losses in this period is not drastically different from the figures later advanced by Hirschman, Preston, and Loi. Furthermore, unlike many scholars Lewy attempts to differentiate the type of civilian death based on region and potential perpetrator, which is helpful as we seek to analyze the political and military climate that surrounded peak years of violence.

Thomas C. Thayer, War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam (Boulder: Westview Press, 1985).

Thayer’s account takes yet another approach to evaluating civilian causalities in the American War by analyzing hospital admission data compiled from participating South Vietnamese and American military hospitals. He largely combines this somewhat simple reconstruction of data with estimates of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Refugees and Escapes findings, offering a more robust estimate of civilian casualties during American involvement in Vietnam.[xxvi] Thayer’s account is particularly useful for the purposes of this study, because he attempts to provide a yearly breakdown of civilian casualties.

Recognizing the obvious shortcomings of this dataset, Thayer concludes that there were over one million civilian casualties in the South alone by the end of American involvement. In this case, a casualty is used to denote any war-related injuries and Thayer places a more conservative estimate of approximately 200,000 civilian deaths in South Vietnam during this period.

“Civilian War Causalities”[xxvii] *from Senate findings

| Year | GVN Hospitals | U.S. Military Hospitals | Total |

| 1967 | 46,783 | 1,951 | 48,734 |

| 1968 | 76,702 | 7,790 | 84,492 |

| 1969 | 59,223 | 8,544 | 67,767 |

| 1970 | 46,247 | 4,6355 | 50,882 |

| 1971 | 38,318 | 1,077 | 39,395 |

As Thayer is clear to point out, the above figures do not include civilian casualties in the North, those never admitted to hospitals, or those admitted to institutions run by private charities or religious organizations.[xxviii] In an effort to move beyond the raw hospital data Thayer explores different government accounts and investigations that attempt to include unreported civilian casualties. While there are several different methods used to yield a more complete estimate, Thayer maintains that the most plausible estimates range from 1,225,000 to 1,350,000 civilian casualties.[xxix].

Thayer presents two different estimates on civilian deaths, one based USAID’s Public Health Division reports and supported by military casualty data, and the other advanced by the U.S. Senate Subcommittee. The first estimate contends that hospital admissions data only accounts for half of all wounded Vietnamese civilians and uses a process of complicated and seemingly random calculations to yield a total of 195,000 South Vietnamese civilians deaths. The Senate Subcommittee, on the other hand, estimates a much higher civilian death count of 415,000.[xxx] Unfortunately, Thayer does not provide a discussion of how the committee reached that figure, and it is difficult to independently verify the calculated figures.

The last important addition that Thayer’s research makes is his effort to differentiate the perpetrators of violence in this period. Once again taking a more narrow window of time, Thayer analyzes they types of injuries reported in hospital admission from 1967 to 1970.

Shelling and Bombing as a Cause of Civil Casualties[xxxi]

| Year | Mine & Mortar | Gun/Grenade | Shelling & Bombing | Total |

| 1967 | 15,235 | 9,785 | 18,811 | 43,849 |

| 1968 | 31,244 | 15,107 | 28,052 | 74,403 |

| 1969 | 24, 648 | 11,814 | 16,183 | 52,645 |

| 1970 | 22,049 | 7,650 | 8,697 | 38,306 |

In his report Thayer makes the admittedly crude argument that injures from mines and mortars were largely inflicted by the communists, those from guns and grenades could be from other sides, while bombing and artillery related injuries and death were the result of the “allies” (US, ARVN, third nation forces). Although recognizing that Americans were responsible for a large portion of civilian deaths, Thayer is adamant the ratio of American responsibility is not as high as many expect and in fact decreased as the war winds down.[xxxii] This trend makes sense, as the United States began withdrawing troops in 1971 and increasingly bombed areas further away from population centers and as discussed above.

Endings

As the war dragged on, several factors crystallized American opposition to the war: the massacre at My Lai (1969) where up to 500 civilians were killed by US forces; expansion of the war to Cambodia (1970); and leak of the Pentagon papers (1971) revealing considerable discrepancies between government actions and public statements. As a result of increasing American public pressure on the U.S. and military pressure on the North, the parties to the conflict began negotiations that resulted in the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973, which governed U.S. withdrawal. Fighting continued between Vietnamese forces, with North Vietnamese forces gaining ground. They took the capitol, Saigon, on April 30, 1975, marking the definitive end to the war and the period of mass atrocities.

Coding

We coded this case as ending when domestic insurgents and North Vietnam defeated South Vietnamese and U.S. forces; hence we also code for a withdrawal of international forces. To account for the targeting of civilians on all sides, we code for multiple victim groups.

Works Cited

Gibson, James William. 1986. The Perfect War: Technowar in Vietnam. Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press.

Hirschman, Charles, and Samuel Preston, and Vu Manh Loi. 1995. “Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A new Estimate.” Population and Development Review, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Dec): 783-812.

Kalyvas, Stathis N. and Matthew Adam Kocher. 2009. “The Dynamics of Violence in Vietnam: An Analysis of the Hamlet Evalusation System (HES)” Journal of Peace Research 46:3, 335 – 355.

Kolko, Gabriel. 1985. Anatomy of a War: Vietnam, the United States and the Modern Historical Experience. New York: The New Press.

Pape, Robert Jr. 1990. “Coercive Air Power in the Vietnam War,” International Security, 15:2, 104-05.

Lewey, Guenter. 1985. American in Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sorley, Lewis. 1999. A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam. New York: Harcourt.

Thayer, Thomas C. 1985. War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Young, Marilyn B. 1991. The Vietnam Wars: 1945-1990. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Notes

[i] There were two incidents, in August 1964 in the Gulf of Tonkin. The first occurred on August 2, 1965 when apparently the US fired first on a North Vietnamese ship as it appeared to be approaching and the Vietnamese ship returned fire; the fact that the US fired first was not made public. The second incident was on August 4, when a US ship claimed that it encountered a North Vietnamese ship and fired on it.

[ii] Young 1991, 50, 57.

[iii] Young 1991, 117, 122.

[iv] Kolko 1985, 147, 167; and Young 1991, 129.

[v] Kalyvas and Kocher 2009.

[vi] Kalyvas and Kocher 2009, 338.

[vii] Kalyvas and Kocher, 2009, 338. The numbers they draw are on from Lowy 1978, 454.

[viii] Young 1991, 162.

[ix] Gibson 1986, 95.

[x] Kolko 1985, 164-67.

[xi] Pape 1990.

[xii] Young 1991, 129.

[xiii] Gibson 1986, 164-68.

[xiv] Young 1991, 235-45.

[xv] Young 1991, 269.

[xvi] Pape 1990, 105.

[xvii] Quoted in Sorley 1999, 170.

[xviii] Hirschman, Preston, and Loi 1995, 807.

[xix] Hirschman, Preston, and Loi 1995, 784.

[xx] Hirschman, Preston, and Loi 1995, 805.

[xxi] The data/calculations for child deaths were not shown in this article.

[xxii] Hirschman, Preston, and Loi 1995, 807.

[xxiii] Lewy 1985, 450-453.

[xxiv] Hirschman, Preston, and Loi 1995, 791.

[xxv] Thayer 1985, 131-33, and Young 1991, 235-51.

[xxvi] Thayer 1985, 127-29.

[xxvii] Thayer 1985, 126.

[xxviii] Thayer 1985, 125-26.

[xxix] Thayer 1985, 128.

[xxx] Thayer 1985, 128-29.

[xxxi] Thayer 1985, 130.

[xxxii] Thayer 1985, 129.