Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

Following the protracted struggle against French rule (see our case study of the war of independence), diverging visions of Algeria’s national identity competed for dominance in the newly independent state. The National Liberation Front (FLN), the secular coalition that had led the independence movement, dominated the government, but after decades of one-party rule and against the rising influence of pan-Islamist ideas in the 1970s and 1980s, struggled to maintain its legitimacy.

In 1988, the price of oil dropped, sparking mass protests and riots by disenfranchised youth. Young Algerians called for the resignation of ruling elites who they felt had betrayed the promises and goals of independence.[i] The government initially resisted reform. Police cracked down on the protesters, killing and injuring several hundreds. However, after protracted internal debates, Algerian President Chadli chose the “Gorbachev gambit” by launching an ambitious political reform program, including a new constitution that ended the political monopoly of the FLN. More than thirty new political parties emerged, and the country entered its brief, ill-fated democratic experiment.

In January 1992, the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) overwhelmingly won the elections, with twice the number of votes than the ruling FLN. Rather than accepting the Islamists’ victory, the military promptly stepped in and cancelled parliamentary elections, banned the FIS and arrested its leaders. It created a temporary Higher State Council, chaired by FLN founder Mohamed Boudiaf, to administer the country. The government imposed a national state of emergency and used a combination of repression and attempted economic reforms to try to pacify the population. However, the official ban of the FIS gave rise to an Islamist insurgency, which launched a sustained campaign against the government. The military responded with brutality, leading the country to civil war.

Atrocities (1992-1998)

The Islamist insurgency that began in 1992 struggled to maintain a unified front, but its weaknesses were further exploited and exacerbated by the government’s tactics. Throughout the war, the identities and strategies of the various warring factions were shrouded in secrecy and confusion. As Salima Mellah argues, “this strategy of confusion, deliberately created and nurtured, gave the generals not only a great scope for action but also lead to the involvement of a great number of actors in the violence, contributing to ensure impunity for those really responsible.”[ii]

Violence began in 1992-3 with insurgent groups launching attacks against police officers and other security units associated with the state. By mid-1993, Islamists were able to consolidate control in a number of areas, from which they could launch further attacks. The escalation of the conflict in 1993 resulted in further targeting of civilians, particularly journalists and intellectuals who were deemed a threat to the Islamists’ agenda. The government responded by building up its security apparatus and creating pro-state militias in addition to the military and police.

The years 1994 – 1995 saw a marked increase in attacks on military and economic targets as well as violence against civilians. The Algerian military mounted an extensive campaign to “make fear change sides,” with the aim of eradicating the FIS and its affiliates.[iii] An NGO, Algeria Watch, argued that as anti-government forces increasingly held the upper hand, brutality shifted from targeted attacks to the broader goal of inciting terror in the population.[iv] The rebellion further splintered into loosely affiliated armed groups with no discernible central command[v]: including the Mouvement pour un État Islamique (MEI), Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA), Front Islamique du Djihad Armé (FIDA), the FIS-sponsored Armée Islamique du Salut (AIS), Ligue Islamique pour le Da’wa et le Djihad (LIDD), Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (GSPC) and Houmat Al-Da’wa al-Salafiyya (HDS), among others.

By 1994, clear ideological and tactical differences had emerged that broadly divided the rebellion into three main camps: The first camp, led by the AIS, presented itself as the armed wing of the FIS. As the most ideologically moderate of the insurgent groups, it did not seek to overthrow the state but aimed to induce reform and pressure the regime to legalize the FIS. The second camp, fronted by MEI and several other groups, aimed at overthrowing the regime and establishing an Islamic state. The third camp, typified by the GIA, was often referred to as the Algerian “Afghans,” as many of its leaders had fought against the Russians in Afghanistan.[vi] GIA was the most radical and ideologically opposed to the AIS, and sought to impose strict Salafi Islamic practice on the population.

The GIA was widely reported to have been infiltrated by state agents who tried to cause divisions within the Islamist camp.[vii] Analysts argue that the army’s manipulation of the GIA was a key factor preventing the development of a unified rebel front.[viii] Unlike the other armed groups, the GIA carried out indiscriminate attacks against civilians, abducted and killed foreigners, planted bombs in public spaces and committed massacres across the countryside.[ix] In 1995, the GIA declared all Algerians to be takfir, or apostates. Violence further escalated in late 1996, when the group massacred hundreds of families in the city of Madea, southwest of Algiers. A series of further massacres followed in July-September 1997 and December 1997-January 1998, in which hundreds of civilians were killed.[x]

The forces associated with the government included several militias that operated as death squads, such as the Organization of the Free Young Algerians (OJAL) and the Organization for the Safeguard of the Algerian Republic (OSRA). Its various tactics included aerial bombardment, napalm, raids and the arrest and torture of suspected insurgents. Most critical to the military’s success was its ability to pit the various rebel factions against one another. As mentioned above, this tactic successfully sparked intra-insurgency fighting, but it also resulted in a plethora of armed movements that were difficult to eradicate militarily or engage politically.[xi] Further complicating the patterns of violence was the government’s support for local defense groups against the Islamists beginning in 1996. This practice unleashed violence at a local level, which often developed a dynamic of its own. Between 1993 and 1997, ca. 1.5 million Algerians were forced to flee their villages.[xii]

The GIA massacres of 1997-1998 precipitated the AIS’s decision to end its armed campaign and negotiate with the government. However, a truce signed on September 21, 1997 proved difficult to implement. The FIS/AIS at this stage of the conflict had limited control over the various groups operating in the country, and many militants refused to comply. Between July and August 1997, and December 1997 and January 1998, hundreds of civilians died in massacres in villages surrounding Algiers. On August 30, 1997, for example, the New York Times reported the killing of 98 civilians in one village over the course of a single night.[xiii] Algerian security forces were often considered responsible for the killings, though the government blamed Islamist forces.[xiv] While the number of fatalities decreased in 1998, violence remained high throughout the year. The first significant decline occurred in 1999, although it certainly did not herald an end to violence.[xv]

Fatalities

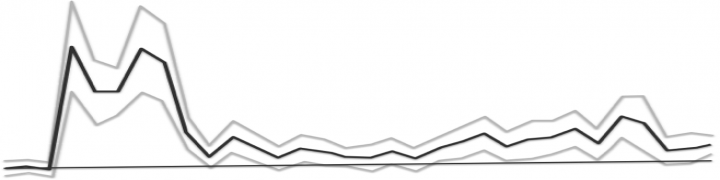

The total death toll of the conflict to this day remains a controversial issue. It is clear that the bulk of the violence occurred between 1992 and 1998, although the civil war continued at a lower level in subsequent years. The most frequently cited death toll is 150,000 up to 1998. This estimate was generated by the Algerian government, which has not made its data sources available. In a speech in Crans-Montana on June 26, 1999, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika initially cited a total of 100,000 people killed (before then, the official death toll had been under 26,000).[xvi] In a second speech on 25 February 2005, Bouteflika revised this estimate and referred to 150,000 fatalities. National human rights organizations such as LAADH argue that the number is likely to have been even greater, potentially exceeding 200,000.[xvii] Similarly, the MAOL (Algerian Movement of Free Officers) in May 1999 reported a total of 173,000 people killed.[xviii]

The actual number of civilian fatalities is likely to have been lower. Using newspaper reports to construct a database of spatially and temporarily disaggregated violent events between 1992 and 2005, Hagelstein arrives at a total of 44,000 fatalities (26,000 killed and 18,000 disappeared). He argues that the government estimate implies a death toll of 850 per month until the end of 1996 and 2,500 per month in 1997-98. Comparing these numbers to his own event data, he notes that for the official figures to hold, 120 out of 140 events between 1994 – 1996, and 400 of 450 between 1997- 1998, would have had to be unreported.[xix]

Algeria Watch does not provide a specific estimate, but notes that Gen. Rachid Laali, head of the Directorate for Documentation and External Security in Algeria, also estimated that 48,000 people had been killed, among them 24,000 civilians. Hugh Roberts (2003) reports a total of 35,000 people killed in the conflict up until 1996, and notes that the majority of fatalities occurred beginning in 1994. However, he does not report the source for this estimate, and this number excludes the phase of heightened violence between 1996 and 1998.[xx] Laitin and Fearon suggest that 10,000 to 30,000 Algerians were killed between January 1992 and October 1994, and 80,000 by the end of the decade. The authors also do not provide a source, nor do they differentiate between civilian and battle deaths.[xxi]

Endings

A number of factors facilitated the decline in violence in the late 1990s. The GIA’s radicalization, stoked by the military, triggered internal divisions among the insurgents. Violence increasingly erupted between the various rebel groups and morphed into predatory behavior that resembled indiscriminate banditry rather than a coherent military campaign. The massacres of civilians by the GIA in 1997 and 1998 helped prompt the AIS’s decision to end its military campaign, alienated civilians and accelerated the breakup of the GIA as groups.[xxii] Even Al Qaeda withdrew its support for the group because it disagreed with the GIA’s position that an entire civilian population could be labeled apostate. As a result, the GIA fragmented into several smaller groups, which subsequently disavowed direct civilian targeting.

Negotiations between the government and more moderate armed groups further helped reduce violence. In September 1997, the AIS announced that it had secretly negotiated a ceasefire with the military. However, this agreement did not result in an immediate end to hostilities (particularly due to the GIA’s ongoing fighting) or a national peace and reconciliation process, given that the FIS/AIS no longer had control over the multiple armed groups involved in the rebellion.

The international community only played a limited role during the conflict, even though the Algerian government in 1997 and 1998 faced increasing international condemnation for its failure to protect civilians.[xxiii] However, neither the European Union nor the UN took action. A UN delegation visited the country in 1998, but its report was criticized for its conciliatory attitude towards the Algerian government and lack of investigation into the massacres.[xxiv]

Abdelaziz Bouteflika won the elections in April 1999, after all of the other candidates had withdrawn. He promptly announced his commitment to striking a substantive deal with the Islamists. In July 1999, he introduced in the National People’s Assembly the Civil Harmony Law, which granted amnesty to those Islamists who renounced violence (except in the case of serious crimes, though de facto amnesty was granted indiscriminately). The accommodation with the Islamists did reduce overall levels violence, as the AIS and other groups disbanded in 2000. However, the government never initiated a comprehensive truth-telling or investigative process, particularly regarding the purported role of government forces in civilian massacres and human rights abuses.[xxv] Violence continued to fluctuate in subsequent years but did return to the levels witnessed in the 1990s.

We coded this case as ending through a strategic shift; there was no clear-cut military defeat, but violence decreased as various actors made political accommodations. The primary forces for moderation were domestic. We note that Bouteflika’s election into office coincided with the decline, hence, have coded this case as coinciding with a leadership change. We further coded this case as one in which the initiator of violence, in this case the government crackdown following elections, was the not the worst, but instead we identify the range of non-state actors in opposition to the government as the primary perpetrators.

Hafez, Mohammed M. 2000. “Armed Islamist Movements and Political Violence in Algeria.” Middle East Journal 54:4, 572 – 591.

Hagelstein, Roman. 1998. “Explaining the Violence Pattern of the Algerian Civil War,” HiCN Working Paper 43, Households in Conflict Network, Institute for Development Studies, March. Available at: http://www.hicn.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/wp43.pdf Accessed January 30, 2017.

International Crisis Group. 2004. “Islamism, Violence and Reform in Algeria: Turning the Page,” ICG Middle East Report Nr. 29, Cairo/Brussels, 30 July. Available at: https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/29-islamism-violence-and-reform-in-algeria-turning-the-page.pdf Accessed January 30, 2017.

Laitin, David and James Fearon. 2006. “Algeria,” Country Narrative, Ethnicity, Insurgency and Civil War project, Available at: http://web.stanford.edu/group/ethnic/Random%20Narratives/AlgeriaRN2.4.pdf Accessed January 30, 2017.

Martinez, Luis. 2004. “Why the Violence in Algeria,” Journal of North African Studies 9:2, 14 – 27.

Mellah, Salima. 2004. “The Massacres in Algeria, 1992 – 2004,” Algeria Watch, May. Available at: http://www.algeria-watch.org/pdf/pdf_en/massacres_algeria.pdf Accessed January 30, 2017.

Roberts, Hugh. 2003. The Battlefield Algeria, 1998-2002: Studies in a Broken Polity. London: Verso.

Tlemcani, Rachid. 2008. “Algeria Under Bouteflika: Civil Strife and National Reconciliation,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February. Available at: http://carnegie-mec.org/2008/03/10/algeria-under-bouteflika-civil-strife-and-national-reconciliation-pub-19976 Accessed January 30, 2017.

Whitney, Craig R. 1997. “98 Die in One of Algerian Civil War’s Worst Massacres,” The New York Times, August 30.

Notes

[i] Tlemcani 2008.

[ii] Mellah 2004, 4.

[iii] Tlemcani 2008, 4.

[iv] Mellah 2004.

[v] Tlemcani 2008, 4.

[vi] International Crisis Group 2004, 10.

[vii] Mellah 2004, 15.

[viii] International Crisis Group 2004, 11.

[ix] International Crisis Group 2004, 11.

[x] International Crisis Group 2004, 13.

[xi] International Crisis Group 2004, 11.

[xii] Martinez 2004, 20.

[xiii] Whitney 1997.

[xiv] Tlemcani 2008, 5.

[xv] Mellah 2004, 17-19.

[xvi] Hagelstein 1998, 16.

[xvii] Mellah 2004, 4.

[xviii] Mellah 2004, 4.

[xix] Hagelstein 1998, 16-17.

[xx] Roberts 2003, 160.

[xxi] Laitin and Fearon 2006.

[xxii] Hafez 2000.

[xxiii] Tlemcani 2008, 5.

[xxiv] Mellah 2004, 46.

[xxv] Tlemcani 2008, 5.