Adapted from “Iraq: atrocity as political capital” by Fanar Haddad in How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq, ed Bridget Conley (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

Perhaps the most consistent feature of Iraq’s dense history of atrocities is the lack of closure: underlying issues fester, justice is denied, grievances mount and the memory of much of what actually transpired is consigned to oral histories and the silent testimony of mass graves. This lack of closure rendered even the country’s recent chance for an ‘ending’—the decline of mass atrocities after 2007—ephemeral: violence subsided but the underlying drivers of conflict remained unaddressed; rather than an ending, the drop in violence proved to be yet another signpost along a drawn-out continuum of conflict.

The legacy of authoritarianism, economic collapse, political dysfunction, social fragmentation and international isolation that the Ba’athist state bequeathed to the new Iraq held all the preconditions for political failure and none of the preconditions for a successful transition to a more benevolent political order. Making matters worse was the questionable way in which regime change was enacted: an illegal invasion that delegitimized the new Iraq, proving extremely divisive both in Iraq and internationally. The incompetence of the occupation and Iraq’s new political classes ensured that the destruction of the state would not be followed by the rebuilding of a functional alternative. Furthermore, the political forces that were ultimately empowered by regime change were inescapably rooted in the prism of identity politics thereby ensuring that Iraq’s social divisions, already strained by years of authoritarianism, economic collapse and accumulated grievances, would become inflamed through political relevance.

In effect, regime change was a turning point in a much longer conflict: it saw the triumph and empowerment of the Shi’a-centric and Kurdish-centric opposition over the pre-2003 state. In many ways, the years after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein have been about the effort to build a Shi’a-centric order in Arab Iraq and the violent rejection that this has produced among Iraqi Sunnis. Hence, the violence can be viewed as the continuation of a single conflict—which perhaps explains the zero-sum nature that Iraqi political discord has often assumed. As one recent study argues, ethno-sectarian entrenchment was not unknown in pre-2003 Iraq; however, the virulent strain of identity politics that so characterised Iraq after regime change was something different

At heart, political violence and socio-political division in post-2003 Iraq have revolved around the issue of state legitimacy in a context of poor governance and failing politics. Both Shi’a and Sunni politicians have supported violent non-state actors—except that in the case of the former, these actors have been aligned with, or at least were not in opposition to, the state. In the case of the latter, these have been anti-state actors. This unfortunate equation reflects the broader divide over views of the legitimacy of the post-2003 order and leads to a vicious cycle that shows no sign of abating: anti-state sentiment among Sunnis feeds into anti-state insurgency that then nourishes the discriminatory, heavy-handed, and sect-centric aspects of post-2003 governance, thereby exacerbating anti-state sentiment among Sunnis by again validating widespread Sunni grievances (real or perceived).

Atrocities (2003-2009)

The drivers of division described thus far must be taken into account when considering the drivers of violence and Iraq’s descent into civil war, which is consistently characterized by violence against civilians. Division need not be synonymous with violence, nor civil war with atrocities, but given the conditions that prevailed in Iraq in the early post-war period it is unsurprising that violence and division were amplified in mutually reinforcing ways. The invasion of Iraq was accompanied by a total breakdown of law, order, governance and authority. There was no restraining force or guiding principle in the early days of the new Iraq. Consequently, the space emerged for all manner of groups to organise and assert their will: from new political parties to civil society organisations to militias to insurgent groups and criminal organisations.[i] As already mentioned the new political order was itself divisive in that it politicised ethno-sectarian identities and empowered polarising figures and organisations. All of this was facilitated and supported by the presence of a no less divisive occupation force.

As a result, anti-occupation and anti-state violence became intertwined. Given the perceived sense of Shi’a ownership of the new order, there was a distinctly sectarian flavour to the violence from a very early stage. In many ways, with time, it became increasingly difficult to clearly delineate the logic of attacking the US-led occupation, the new state or the Shi’as. In parallel, the lines separating fighting for the state, fighting terror, and attacking Sunnis also became more ambiguous over time. Almost immediately after the fall of the regime score settling and violence, political and/or criminal, became a feature of the new Iraq. It is worth noting that Shi’a militants, many of whom were affiliated with the newly empowered political elite operated from the earliest days of the new order with their assassination squads targeting Ba’ath sympathisers and former Ba’athists. A profound sense of insecurity amongst Sunnis and Shi’as at both the elite and at the mass level created a classic security dilemma, whereby mutual fear led to increased group mobilization—both in the sense of armed mobilization and in the mobilization of group identity.

The violence in 2006 and 2007 included some internal variation, but spanned most of the Arab Iraqi geography. Not all forms of violence followed the logic of the Sunni-Shia schism: for instance, intra-Shia violence (eg Karbala in 2008 and Basra 2007); the fight against Al Qaeda (eg Anbar & Diyala, 2007); the fight against the US (eg Anbar, Baghdad) and inter-militia violence (Baghdad 2006-2008, Basra 2007). Further, Sunni anti-US insurgent activity declined at the time that Shi’a anti-US insurgents gained momentum.

By the time Iraq’s first elected government was formed in 2006, the state was composed of competing forces many of which actively participated in the ever-escalating violence. Most notoriously the Ministry of the Interior came to play a prominent role in the civil war in Baghdad and beyond particularly after the elections of 2005 and the granting of the Ministry to the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq whose paramilitary wing, the Badr Corps, were now able to operate with impunity from the Ministry. Sources describe the emergence of a parallel chain of command reporting to Badr affiliated cadres and who held sway over the formal hierarchy within the Ministry. In effect what emerged was a shadow Ministry within the Ministry of Interior: above the formal ministerial structure there existed a sect-centric militia-led force that was leading the fight against anti-state militants and their support networks.

A similar pattern developed across the various organs of the state, in effect halting whatever efforts existed to build the state’s governing capacity. An enduring result of this dynamic was the institutionalization of violence and narrow group interests. This resulted in a pronounced state of fragmentation across the state and within state organs. For example, intelligence officers complained that they had to contend with party and militia-affiliated intelligence networks whose information and recommendations often took precedence over ostensibly national intelligence organs.[ii] Furthermore, promotions, assignments and rotations were subject to intense political interference, thereby hampering institutional effectiveness. A member of Baghdad’s Provincial Council described competing criminal, militant and political networks within single institutions in 2006-2007:

There were instances of real criminality [referring to extortion and strong-arm tactics for financial gain] and some unbelievable methods of killing that were happening within institutions. You may be surprised to hear that the civil war [also] happened within the institutions: people disappeared not [only] outside on the streets; many people were abducted from their offices for sectarian reasons using official orders and official channels… So sectarianism was bigger than just this one is Sunni and that one is Shi’a: it affected the state’s infrastructure and institutions. Gangs! It was gangs![iii]

The Councilman’s recollections highlight an important point: while much of the violence was undeniably sect-coded, various other armed groups competed within and across sectarian lines, and within and against the state for a greater share of its power and resources.[iv] This dynamic has continued in one form or another, highlighting the fact that the system that emerged in Iraq was shaped by conditions of civil war: opacity, diffusion of power, dysfunction and kleptocracy. This has been both a symptom and a cause of the failure of the post-2003 state-building project. It has allowed for the proliferation of armed groups and the perpetuation of violence. Ultimately, no other factor oiled the cycle of violence more than state weakness and fragmentation.

The Iraqi state lacked the capacity to enforce a victor’s peace and Iraqi politics were too fractious and dysfunctional to enact a meaningful reconciliation process. Indeed, it can be argued that political violence, like many other ills afflicting contemporary Iraq such as identity politics or corruption, was not an anomaly but a defining characteristic of the current order. As argued by Charles Tripp:

“violence in Iraq has now become a central part of the practice of power, both by the government and by certain non-governmental agencies, some of them bitterly opposed to, but others enmeshed in webs of government practice.”[v]

Indeed, what Tripp referred to as the ‘grammar of violence’ continued to inform political bargaining at the elite level and dictated state response to political conflict.[vi] One even suspects that political violence in the new Iraq has become so entrenched and so banal that government policy deals with it much the same way as unemployment is dealt with elsewhere in the world: as something to be managed and contained rather than something that needs eradication.

Fatalities

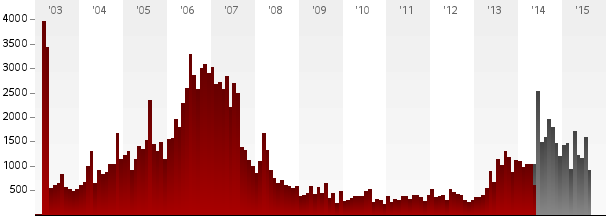

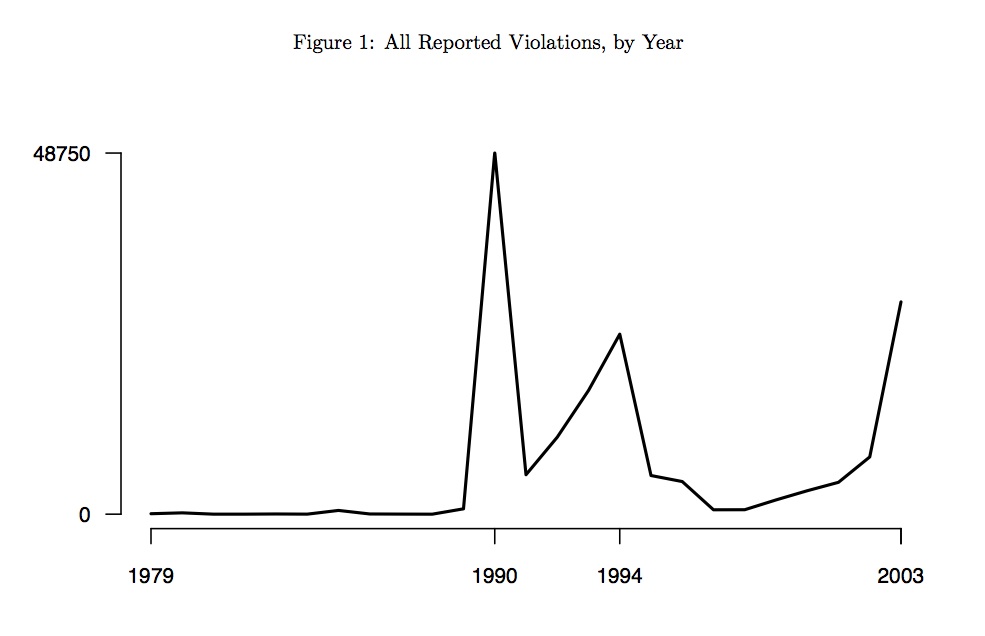

Statistics taken from Iraq Body Count[vii] demonstrate that only 2010 – 2011 represent a decline such as fits the parameters of this project, and even then, they only just fit:

Beginning in late 2007 and early 2008 Iraq seemed to have achieved a decline in mass violence and looked like it was set on a more positive trajectory. By any measure, a drop of monthly deaths from highs of over 3,000 killed in July 2006 to just over 600 deaths two years later in July 2008 was a positive achievement. Indeed the average monthly violent death toll continued to hover around 300 until 2013 (Iraq Body Count).

Endings

The drivers behind the reduction in violence beginning in late 2007 have been the subject of much research, particularly on the question of whether or not the United States’ military ‘Surge’ policy was the primary cause. Broadly speaking, there is consensus that no single factor, Surge or otherwise, can be solely credited with the security improvement in 2007-2008 that generally lasted until 2013. A number of interrelated and interdependent factors, difficult to recreate individually, let alone in tandem, combined to create what at the time seemed like a possible ending. Various scholars have suggested a combination of the following: the military losses of Sunni militants to the state and Shi’a militias; the extra U.S. troops and reorientation of U.S. counterinsurgency policy afforded by the Surge; the Awakening movement; sectarian cleansing; the ‘freeze’ or standing down of the Mahdi Army (one of the most prominent and destabilising forces in the violence of 2006-2007); and finally the growing strength and confidence of the state and the Iraqi security forces. The multiplicity of factors in part reflects the multiplicity of conflicts and drivers of conflict by early 2007: sectarian violence; anti-state violence; anti-occupation violence; intra-Shi’a violence; intra-Sunni violence; external subversion; criminality and weak state institutions.

Clearly, no single driver can account for the drop in violence in 2007. All of the factors discussed here worked interdependently and all were essential to the success of each other. The loss of the civil war incentivised Sunni political and insurgent forces to negotiate and work with the Americans and with the Iraqi government. This was a key driver behind the rise of the Awakening. In turn the Awakening was facilitated by the Surge, and conversely it ensured the Surge’s effectiveness, which in turn provided the opening for the state to focus on consolidating gains and building capacity. The resulting improvements in security led to the isolation of and eventual freeze on Mahdi Army activities. Ultimately this worked towards enhancing the state’s legitimacy and broadened popular acceptance (begrudging or otherwise) of the post-2003 order.

These were the factors that, beginning in mid- to late 2007, led to the decline in mass violence and mass atrocities. They were a product of the socio-political moment, and are, as such, impossible to replicate– something that is particularly unfortunate given Iraq’s renewed and urgent need for an end to mass atrocities. These factors do not provide a formula for ending, but rather describe a political opening that was not seized.

The years 2007-2013 saw a lull in violence and a relative stabilisation of the state that afforded Iraq a real opportunity for political progress. This was squandered as a result of several factors: the controversial elections of 2010, the withdrawal of U.S. forces and the highly corrosive politics of Nuri al Maliki’s second government (2010-2014). More fundamentally, however, the lull in violence was not accompanied by a political effort to address the underlying roots of conflict.

The years 2008-2013 were the new Iraq’s most promising, yet these were also the years in which the modest gains of 2007-2008 were ultimately reversed. The moment created by the Awakening movement, the tentative–albeit begrudging–Sunni acceptance of the new Iraq’s political realities, the waning of sectarian entrenchment, and, ultimately, the drop in mass violence in 2007, began to vanish. By 2013 what little progress had been made on these fronts had been reversed and the clash between Shi’a-centric state building and Sunni rejection was as relevant as ever. Sunni political participation was undermined by the elections of 2010, the ineffectiveness of Sunni political leadership, the centralising and increasingly autocratic second government of Nuri al Maliki and particularly his targeting of top Sunni leaders in 2011-2013. Militant networks were still active and steadily gaining ground with every year of political failure that passed. In fact it was in these years that the Islamic State of Iraq was able to reconstitute itself and expand its operations before entering the Syrian arena and eventually launching its audacious sweep across vast swathes of Iraq in the summer of 2014 under its new banner of the Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham – soon to be rebranded into the Islamic State. With hindsight, it would seem that the return to mass violence was the unavoidable concomitant of the unsustainability of the Iraqi political order in the years 2010-2014.

Coding

This was a very difficult case to code. In the end, we decided that the dynamic of decline in violence was best captured by a process of strategic shifts, under the influence of moderating forces both from domestic and international actors. The decline coincided with the partial withdrawal of international forces, but it appears that the U.S. drawdown was a response to the decline in violence rather than a cause for it. Nonetheless we code for withdrawal. We also coded for multiple victim groups and note that the actor who initiated the period of atrocities, the U.S., was the not the primary perpetrator of mass atrocities. While assigning responsibility for violence in this case is often difficult, it appears that non-state actors (on multiple sides) were the primary perpetrators.

Recognizing that others may dispute our analysis, we also provide a secondary coding of defeat, to capture the military dynamics whereby the surge of US and Sunni armed actors gained advantage over Shi’ite forces.

Works Cited

Boyle, Michael J. 2009. Bargaining, Fear and Denial: Explaining violence Against Civilians in Iraq 2004 – 2007.” Terrorism and Political Violence 21: 261 – 287.

Haddad, Fanar. 2016. “Iraq: atrocity as political capital.” How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq. ed Bridget Conley-Zilkic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Iraq Body Count. 2016. “Documented Civilian Deaths from Violence.” Available at: https://www.iraqbodycount.org/database/ Accessed July 1, 2016.

al Jaza’iri, Zuhair. 2009. Harb al ‘Ajiz. Beirut: Al-Saqi.

Rayburn, Joel. 2014. Iraq After America: Strongmen, Sectarians, Resistance. Stanford: Hoover Institute Press.

Tripp, Charles. 2007. “Militias, Vigilantes, Death Squads: Charles Tripp on the Grammar of Violence in Iraq.” London Review of Books 29:2, 30 – 34.

Notes

[i] al Jaza’iri 2009.

[ii] Haddad 2016, 190.

[iii] Haddad 2016, 190.

[iv] Boyle 2009, 268.

[v] Quoted in Haddad 2016, 191.

[vi] Tripp 2007.

[vii] Iraq Body Count 2016.