This case study is an adaptation of “Sudan: Patterns of violence and imperfect endings” by Alex de Waal in How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Iraq, ed Bridget Conley (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

The first Sudanese Civil War, also known as the Anyanya Rebellion (1955-1972) was concluded through a negotiated settlement that provided the South a significant degree of autonomy. However, in 1983 President Nimeiri undertook several decisions that abrogated key terms of the agreement, including imposing Shari’a Law across the entire country and abolishing the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region. In response, southern rebels, known during this conflict as the Southern Peoples Liberation Army (SPLA) took up arms against the state.

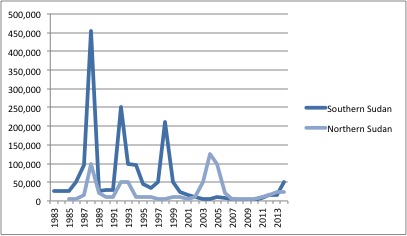

The second Sudanese civil war lasted from 1985 through 2005, and was fought primarily between forces aligned with the northern, Khartoum-based government against those aligned with the southern-based rebels, and within the southern rebel movement. Included in this study is also a government offensive against the Nuba Mountains, which is part of the North. The conflict ended with a peace agreement, mediated by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) in East Africa, and supported by the region and wider international community. Throughout, the conflict was marked by violence against civilians, which caused the deaths of a rough estimates of 1 – 2 million civilians, many of them a result of starvation and disease. The chart, below, captures the overall pattern of conflict intensity. However, it is not possible, given the paucity of data, to more accurately break down the numbers by annual or incident-specific tolls, nor by direct killing versus death caused by the general conflict conditions. Best estimates suggest that as the long-standing conflict was winding down—with fatalities likely falling below 5,000 a year by 2004—it overlapped with the beginning of another conflict, this time in the western area of Darfur (2003 – 2005) [treated in this study as a separate case].

Below, we introduce the most significant spike of lethal violence from the conflict.

Atrocities

Figure 1: War-related deaths in Sudan 1983-2014

Source: Alex de Waal (2016), estimates of total civilian deaths related to conflict in southern Sudan 1983-98 from Burr 1998; for Darfur from CRED 2005.

Below we introduce several of the factors that contributed to the spikes of violence over the course of the conflict.

1980s

Militia Raids

From the beginning of the war (1985), the Government of Sudan mounted counter-insurgency “on the cheap” through tribal militia.[i] The unstated rationale for this was the parlous condition of government finances throughout the 1980s.[ii] The earliest militia included southern Sudanese “friendly forces,” which carried out widespread killings, mainly of ethnic Dinka civilians and SPLA recruits.[iii] The most notorious militia were drawn from the Arab groups who lived on the northern side of the internal north-south boundary, which practiced a scorched earth policy, destroying communities suspected to support the SPLA, and rewarding themselves by stealing cattle and looting whatever else they could find. Commonly known as murahaliin (“nomads”), these militia killed, plundered, burned and raped their way through a huge swathe of southern Sudan from 1985 to 1989.[iv] They also abducted thousands of women and children into servitude and created a famine of exceptional severity among the displaced.[v]

In 1987, when the militia unexpectedly encountered a large SPLA unit and suffered many fatalities, they took reprisals on displaced civilians in the south-eastern Darfur town of ed Da’ien, killing more than one thousand, many by burning alive inside railway wagons.[vi] Large-scale killing and displacement reached a peak in 1988. This episode of mass atrocities began to subside when the areas accessible to the militia had been thoroughly ravaged, and because SPLA units penetrated the area and could now challenge the army.

Less well documented during this time period are the Wau massacres (1986-87) and mass executions in Kadugli (1988).

The dry season of 1989 witnessed reduced raids.[vii] Political factors also contributed to this incomplete ending. One element was local. The tribal leadership of the Baggara Arabs prevailed upon their kinsmen who were commanding the militia, that they should reduce the violence, on the grounds that they would need at some point to live together with the Dinka as neighbors. During 1990-94 there were a number of local truces that included setting up seven cross-border “peace markets” and some cooperation in finding and returning abducted children. At a national level, the army’s General Headquarters was opposed to the war in general and the militia strategy in particular, and pressed the government to rein in the militia and to engage in peace talks. As a compromise, the government formalized the militia into the Popular Defense Forces (PDF), putting them on salaries and within the command and control structure of the army. The more consolidated control mechanisms limited the license for atrocities that served no military purpose, and the level of raiding by the Murahaliin never again reached the same levels as 1985-89.

Finally there was an international dimension. While the war did not spark international outrage, and the first reports by human rights organizations were published in 1989[viii] and 1990[ix] the humanitarian disaster did belatedly generate a response. Journalists visited the displaced camps in the summer of 1988, alongside aid workers. Meanwhile, aid workers reported on death rates in the camps that were higher, by an order of magnitude, than those recorded in other famines of the 1980s. The fact that internationally-donated aid had stood untouched in railway wagons for over a year, just yards from a camp where children were starving to death, caused outrage. This generated pressure on the government to allow relief to reach the famine victims, and in time led to the launch of Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) in January 1989. The presence of aid workers made it impossible for the slaughter to continue in secret.

1990s

War within the South

The SPLA relied on support from the Ethiopia, which failed beginning in May 1991, when insurgents defeated the Ethiopian government headed by Mengistu Haile Mariam. Shortly thereafter, in August 1991, the SPLA began to collapse when three senior SPLA commanders, Riek Machar, Lam Akol and Gordon Kong, based in the town of Nasir, declared that they had overthrown Garang. Their platform was that the SPLA had been run in a dictatorial and incompetent manner. They did not intend an ethnic coup, but they did not succeed in obtaining the timely support of key Dinka commanders who sympathized their position, and within days the split degenerated into a confrontation between the rebellious “Nasir Faction,” mainly ethnic Nuer and Shilluk, and the mainstream “Torit Faction” led by Garang, retaining the loyalty of the Dinka, and named for his headquarters. An attempt by Riek Machar to march on Torit turned into an exercise in mobilizing a Nuer tribal force, popularly known as the White Army, which got as far as Garang’s home town of Bor, in Jonglei, where they massacred 2,000 civilians on 15 November 1991. This was the signature atrocity of a period of internecine killings that continued throughout the decade. But, as indicated above, it was different mainly in visibility rather than scale to what had gone before.

The period of the most intense reciprocal ethnic killings came to an end in 1994, through a political process of internal reconciliation. Under pressure from commanders, chiefs, religious leaders and a wide array of southern Sudanese, in the country and abroad, the SPLA leaders were pushed to reconcile. This culminated in early 1994 in the SPLM’s first convention, at which delegates welcomed back dissenters and adopted a programme of institution-building and democratization.[x] Garang subsequently circumvented or subverted most of the decisions of the convention, but it nonetheless served a purpose of creating a forum in which southern Sudanese could meet, legitimizing discussions outside the tight control of the commander-in-chief, and reducing internal violence. It took some years for the key mutinous commanders to return to the fold, and other discontented commanders mutinied in the meantime—leading to a particularly vicious round of killing and starvation in 1998—but the worst of the mass atrocities were over.

The Nuba Mountains: 1991 – 1992

The government of Sudan blocked outside access to South Kordofan (part of northern Sudan) in 1991, and in 1992 the government began its declared jihad against the Nuba in the Nuba Mountains, which included both a major offensive against the SPLA, and a genocidal and ethnocidal campaign against the Nuba. The Nuba are an ethnically diverse group, with religious practices ranging from Muslim to Christian to indigenous.

International mujahideen trained local fighters for the jihad and a fatwa was issued in support of the cause. Although the governor of South Kordofan declared the jihad, it was supported by President Omar al-Bashir, and conceived within the Arab and Islamic Bureau headed by Hassan al-Turabi. The purposes of the jihad were threefold: social transformation of the Nuba, counterinsurgency, and land grab. The social transformation aimed to Islamicize the Nuba and eradicate un-Islamic practices. This aim ignored the fact that many of the Nuba were Muslim. To address this inconsistency, the fatwa issued declared Nuba Muslims to be apostates.

The genocidal-jihadist policy included destruction of villages by ground forces and air power, death squads targeting local leaders, disappearances of local intellectuals, mass rape designed to change the next generation of Nuba society, famine, and the relocation of the Nuba to “peace camps.” By 1992, the government had relocated over 160,000 people, with plans to resettle 500,000 more.

The establishment of peace camps is perhaps the signature of this campaign; the Nuba were relocated to areas of Northern Kordofan, where it was expected they would serve as laborers. According to Komey, the sociocultural transformation that took place in the peace camps included the banning of indigenous religious practices, education which portrayed the Nuba as inferior to Arab culture, and manipulation of Nuba leaders through economic incentives.

The ending was related to three primary factors. First, lack of consensus was found at all levels within the Sudanese government and allied fighters. Vice President Zubeir was an opponent to the campaign, and Hassan al-Turabi never signed on to the fatwa that was issued for the jihad. Additionally, some of the foreign fighters refused to fight when the realized that some of the Nuba were Muslim. Second, Sudanese communities were appalled at the conditions in which the Nuba were living when they saw the displaced Nuba in Northern Kordofan. Communities took it upon themselves to deliver food and medicine, and expressed their dissatisfaction with the conditions, contributing to the retreat of the militants. Third, resistance was perhaps the most decisive factor. The Nuba supported the SPLA troops, and the fighters fought hard against the opposition. In 1992, the SPLA was able to slow down the advance of government troops, and in May the government falsely declared they had won Tullishi Mountain and withdrew.

War continued, though was intermittent, and the parties fought each other to a standstill. A ceasefire was signed in 2002, brokered by the U.S. and Switzerland.

Oilfields

In 1997, as the government made a major effort to control the oil-producing areas,[xi] violence returned to the areas that along the borders between Sudan and southern Sudan. The government’s main tool for consolidating control over the area was renting the allegiance of local leaders so that military activities were undertaken under the command of local men.[xii] Hundreds of fighters were killed in battles and hundreds more civilians killed in massacres, and by 2001 more than 200,000 people were displaced.[xiii] It was an anarchic conflict, organized around loyalty payments to militia.

After the majority of the local militia commanders defected and made alliances with the SPLA in 1999-2000, the government strategy changed to one of dispatching its own forces and northern militia to clear the oil producing areas, leading to the deaths of many thousands and the displacement of a further 130,000.[xiv] This phase of the conflict was polarized, targeted and systematic, which distinguishes it from most other large military offensives in Sudan. However, estimates for total fatalities do not match those of other major episodes of mass atrocity.

The atrocities in Upper Nile subsided when the government had achieved its immediate military objectives, which were securing the area for oil production. However, the SPLA’s military threats to the oil producing areas ended only with the peace negotiations that brought an end to the civil war itself, and it was only during the period of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that displaced people were able to return home in relative security.

Fatalities

The number of deaths caused by the war between southern-based insurgents, the Sudan Peoples Liberation Army and the government of Sudan (1983 – 2005) is almost ubiquitously cited as 2.5 million people. The number stems primarily from the work of Millard Burr, a consultant for the U.S. Committee for Refugees. According to his testimony before U.S. Congress, his first ‘working paper’ documenting war related deaths between 1983 and 1993 was produced following comprehensive analysis of efforts to document the patterns of violence in the country:

After sifting through hundreds of documents and thousands of news reports, and after collecting hundreds of data points, I concluded that during the decade, at least 1.3 million Southern Sudanese died as a result of war-related causes and government neglect.[xv]

Burr published a second working document in 1998,[xvi] following similar methodology, and adding information about government aerial assaults, and attacks on the Nuba Mountains, in Equatoria, Upper Nile and Bahr al-Ghazal, which, he wrote, ‘suggests that no fewer than 600,000 people have lost their lives since 1993. Thus, no more than 1.9 million southern Sudanese and Nuba Mountains peoples have perished since the inception of the cataclysmic civil war that began in 1983’.

However, Burr’s estimation does not disaggregate those directly killed from those who died as a result of the humanitarian crisis created by the war. A very rough estimate of civilian fatalities would suggest a minimum of 100,000 civilian direct deaths caused by violence. The Sudanese government itself states that between May 1992 and February 1993, 60-70,000 Nuba were killed. Although exact figures are difficult to find, the website “Occasional Witness” puts war-related deaths of the Nuba alone between 100-200,000. The number of dead from other periods of heightened violence, like the Bor Massacre are sometimes documented, but mostly, the numbers for this conflict are very rough.

Endings

Sudan and now South Sudan have experienced decades of armed conflict with devastating impact on the civilian populations. Each phase of fighting has ended through mediation, followed by a short period of quiet, and then a new round of fighting, displacement and death. The “endings” in 2005, of the conflict between the north and south ended through heavily internationalized mediation.

Alex de Waal describes this pattern of escalation and reduction:

Mass atrocities in Sudan have no clear endings. The country’s protracted civil wars have been punctuated by major military campaigns that involve large-scale killings and war crimes perpetrated by regular and irregular forces. Four times over the last thirty years, operations of this kind have killed tens of thousands of civilians, and caused hundreds of thousands to die from displacement, hunger and disease. Each episode of mass atrocity occurs for different reasons, including fear-driven counter-insurgency, ideological ambition, and clearing areas to seize their resources, but they resemble one another in their pattern of ethnically-targeted destruction of civilian communities. These episodes do not end clearly or decisively. Rather, killings diminish as the pattern of violence changes from a bipolar confrontation to fragmented or anarchic conflict. This is related to the way in which Sudan’s wars end neither in outright victories nor durable peace settlements, but rather in political realignments that reconfigure and may reduce violence. Sudanese live under the constant threat that war and mass atrocity may flare up again.

[…]

Large-scale killings come to an end when the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) have achieved immediate military goals, but do not sustain the effort to decisive victory. The reasons for that inability include: (a) internal dissension among the ruling elite; (b) resistance from local rebels; and (c) resource and organizational constraints on sustaining a campaign. The immediate outcome is not a definitive ‘ending’, but a different pattern of violence, less polarized and more ‘anarchic,’ less intense but perhaps more widely spread. Irrespective of the rationale for initiating the violence, the patterns of (incomplete) endings are similar.

Coding

We code the mass atrocities in South Sudan as ending through strategic shift, due to moderation within domestic actors, under international pressure to negotiate an end to the conflict. The war produced no clear victor, hence we note that it had stalemated. We also code for multiple victim groups, to include those targeted by the government for various logics, as well as those killed during intra-southern violence. We further note that a non-state actor, various Southern-based groups and militias allied to the government, were secondary perpetrators of atrocities.

Works Cited

Africa Watch. 1990. Denying “the Honor of Living,” Sudan: A human rights disaster. London: Africa Watch.

African Rights. 1995. Facing Genocide: The Nuba of Sudan, London: African Rights.

African Rights. 1997. Food and Power in Sudan: A Critique of Humanitarianism. London: African Rights.

Amnesty International. 1989. “Sudan: Human rights violations in the context of civil war,” London.

Anonymous. 1987. “Sudan’s Secret Slaughter,” mimeo, 1987; Africa Watch1990

Burr, Millard. 1999. Testimony of J. Millard Burr, Consultant, U.S. Committee for Refugees on The Crisis Against Humanity in Sudan Before the Committee on International Relations, Subcommittee on International Operations and Human Rights, U.S. House of Representatives 27 May 1999. http://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/testimony-j-millard-burr-consultant-us-committee-refugees-crisis-against-humanity-sudan, accessed 15 September 2016.

Burr, Millard. 1998. Working Document II: Quantifying Genocide in Southern Sudan and the Nuba Mountains, 1983-1998, U.S. Committee for Refugees, December 1998, http://www.occasionalwitness.com/content/documents/Working_DocumentII.htm, accessed 15 September 2016.

Christian Aid. 2000. 2000. The Scorched Earth: Oil and war in Sudan. London: Christian Aid, October.

deGuzman, Diane. 2002. Depopulating Sudan’s Oil Regions, edited by Egbert G. Utretch: ECOS, May 14.

de Waal, Alex. 1987. “The Perception of Poverty and Famines.” International Journal of Moral and Social Studies 2: 3, 251–262.

de Waal, Alex . 1994. “Some Comments on Militias in Contemporary Sudan,” in Martin Daly and Ahmed al Sikainga (eds.) Civil War in the Sudan, London, British Academic Press.

de Waal, Alex. 2015. The real politics of the Horn of Africa: money, war and the business of power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

de Waal, Alex. 2016. in ed. Conley-Zilkic, Bridget. How Mass Atrocities End: Studies from Guatemala, Burundi, Indonesia, The Sudans, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Iraq. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS). 2001. Documentation on the Impact of Oil in Sudan. Utrecht: ECOS, May 29.

Human Rights Watch. 2003. Sudan, Oil and Human Rights. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Keen, David. 1994. The Benefits of Famine: A political economy of famine and relief in southwestern Sudan, 1983-1989, New Haven, Yale University Press.

Mahmoud, Ushari and Suleiman Baldo. 1987. “El Diein Massacre and Slavery in the Sudan,” Khartoum, mimeo.

Andrew Mawson, “Murahaleen Raids on the Dinka 1985-89,” Disasters, 15.2, 137-149, 1991. Mawson 1989

Patey, Luke. 2014. The New Kings of Crude: China, India, and the Global Struggle for Oil in Sudan and South Sudan. London: Hurst.

Rolandsen, Oystein H. 2005. Guerrilla Government: Political changes in the Southern Sudan during the 1990s, Uppsala, Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

Notes

[i] African Rights 1997.

[ii] de Waal 2015.

[iii] Anonymous 1987; Africa Watch 1990.

[iv] Amnesty International 1989.

[v] Keen 1994.

[vi] Mahmoud and Baldo 1987.

[vii] Mawson 1991.

[viii] Mawson 1989.

[ix] Africa Watch 1990.

[x] Rolandsen 2005.

[xi] Patey 2014.

[xii] Christian Aid 2000; European Coalition on Oil in Sudan 2001; Human Rights Watch 2003.

[xiii] Human Rights Watch 2003, 313-319.

[xiv] deGuzman 2002.

[xv] Burr 1999.

[xvi] Burr 1998.