Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

Categorized as a low-intensity, intra-state conflict, the Mozambican Civil War is notorious for the scale of human suffering and lives lost over its fifteen-year duration. Just two years after ushering in independence from Portugal, Mozambique’s liberation movement, the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO), encountered resistance from the armed rebel group Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO). Initially backed by the Rhodesian Central Intelligence and the South African Military Intelligence Directorate, RENAMO’s first recruits consisted of dissident elites that splintered from FRELIMO in protest of its increasingly stringent socialist policies for development. Their grievances chiefly arose from the government’s policy of persecution of those that had benefitted under the Portuguese colonial regime, as well its legislation declaring all political opposition illegal.[i] As the conflict evolved, RENAMO’s guerrilla offensive came to be defined by forced recruitment, systematic acts of violence against Mozambican civilians, and a pillage economy. Interviews with civilians indicate that RENAMO was responsible for over 80% of violent incidents through the war.[ii]

Atrocities

Beginning in 1976, the conflict was waged by a small force of mostly voluntary RENAMO soldiers in the border regions of Gaza and Manica. By 1981, however, the dynamics quickly began to change after the fall of the Rhodesian government.[iii] Most significantly, RENAMO’s inward expansion into Mozambique required rapid recruitment, achieved overwhelmingly by the forced conscription of unwilling civilians.[iv] Levels of violence against civilians began to steadily escalate, reaching peak intensity by 1989.[v] Direct killing of civilians, along with a myriad of human rights violations, manifested in murders, routine brutality, and large-scale massacres. In addition to using indiscriminate violence during military operations, RENAMO leveraged terror to enforce control over new recruits and the local population. New recruits were coerced to murder their family members, while other common acts ranged from facial and bodily mutilation to the use of land mines and burning people alive.[vi] Forced relocation to “control areas” occurred frequently, usually following abduction from government-held areas.[vii] Massacres of six or more individuals characterized more than 40% of all recorded attacks.[viii] The largest massacre in the war took place in the southern village of Homoine in 1987, with a death toll of 424.[ix]

RENAMO’s resort to widespread violence was a critical aspect of its two-pronged strategy to cause government collapse through the meticulous destruction of infrastructure and the calculated humiliation of FRELIMO.[x] Under Afonso Dhlakama’s leadership, RENAMO sought to weaken the government to the point of surrender or negotiation of a power-sharing agreement.[xi] To this end, RENAMO engaged in scorched-earth tactics targeting all government-provided or enabled services; it is estimated that 40% of Mozambique’s agricultural, communications, and administration infrastructure was destroyed,[xii] as was 46% of the country’s health services, with horrific implications for total war-related deaths.[xiii] In addition to facilitating coercive recruitment, violence proved to be an effective means of inspiring compliance and extracting food, resources, and intelligence about FRELIMO from local populations. These acts of terror and the destruction of government and civilian property communicated to civilians that the FRELIMO government could not adequately provide for their protection.

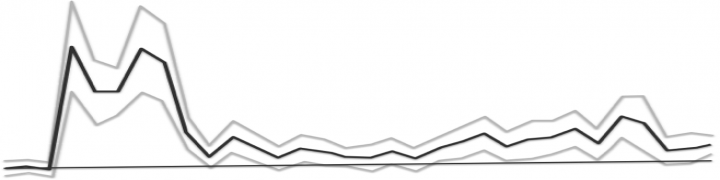

While the character and tactics of violence remained constant over time, the timing and regional patterns of RENAMO’s perpetration of violence directly corresponded to its relative position of power in the conflict. To counter low popular support and weak control in the southern provinces,[xiv] RENAMO launched nearly double the number of attacks as compared to the center and north.[xv] The south also experienced a higher intensity of massacres, claiming over 70% of incidents with more than fifteen victims.[xvi] Overall levels of violence sharply increased after RENAMO reached a military stalemate with FRELIMO in 1986.[xvii] The high-profile massacres at Homoine, Taninga, and Mandlakazi all took place in 1987, with a conservative estimate of 1,668 direct killings taking place between 1987 and 1992.[xviii]

Fatalities

Estimates of total civilian deaths during the civil war vary widely, ranging from 700[xix] to 100,000[xx] direct killings and from 600,000[xxi] to 1 million[xxii] war-related deaths overall. Conservative estimates rely solely on verified primary sources, such as media reports and personal interviews, whereas higher estimates tend to arise from the extrapolation of location-specific data to the broader country population. The higher estimates on total war-related deaths are usually derived from UNICEF and other international agencies.

Analysis of direct civilian killings reveals several findings. First, the most commonly cited number provided for intentional, RENAMO-perpetrated civilian deaths is 100,000. This estimate traces back to the so-called “Gersony Report,” commissioned by the U.S. State Department in 1988.[xxiii] After years of low media coverage and unconfirmed rumors regarding the brutality of RENAMO, the researcher Robert Gersony conducted a formal investigation into the nature and extent of the civil war’s fatalities. In interviews with approximately 170 refugee families randomly selected within the refugee camps, Gersony gathered that they had collectively witnessed the murder of 600 unarmed civilians. Assuming his sample to be representative, Gersony then extrapolated this estimate to the rest of the population and reached an estimate of 100,000 killed by 1988. His projection method, which did not rely on a random sample of the entire country, has been criticized by some as statistically unreliable. Further, his report came at a moment when the United States was re-evaluating its covert support for RENAMO, and his fatality estimates were a “tool in bureaucratic infighting” between anti-communist and constructive engagement advocates.[xxiv]

Despite the Gersony Report’s caveats, the researcher William Minter concludes in his analysis of RENAMO-perpetrated violence that Gersony’s findings align with those of numerous journalists, relief workers, and anthropologists. Drawing on the work of Kenneth Wilson, Otto Roesch, and Christian Geffray, as well as his own field work, Minter argues that the massive scale and brutal, coercive nature of RENAMO’s violence is well-documented. While Minter remains skeptical of Gersony’s 100,000 range, he demonstrates that all adult civilians and ex-combatants interviewed in each study consistently tell the same story of indiscriminate violence.[xxv]

With the aim of establishing a more accurate account of direct violence against civilians, Jeremy Weinstein and others have constructed new databases based strictly on press sources and eyewitness accounts. Weinstein and Francisco recorded 829 civilians killed from 1976-1994, with 692 attributed to Renamo;[xxvi] comparable databases estimate 1,668 civilians killed between 1987 and 1991[xxvii] and 1,400 killed between 1989 and 1992. While key events such as the massacre at Homoine are noted across numerous sources, other large-scale incidents are observed inconsistently. A highway massacre of 278 people in 1987, for example, is included in a 1992 report by Africa Watch,[xxviii] but it is not reported in the KOSVED conflict project.[xxix] One source records 1,000 killed in 1991,[xxx] while another reports 525.[xxxi] Such inconsistency reinforces the difficulty of ascertaining the true scale of atrocities in Mozambique.

A final aspect of consideration is an assessment of civilian deaths from famine and disease while living in RENAMO-controlled areas. Figures such as UNICEF’s estimate of 600,000 war-related deaths correlate to two waves of severe famine that were induced by the civil war. Both RENAMO and FRELIMO practiced policies of forced relocation into fortified villages, ostensibly to protect civilians; in practice, large-scale relocation, accompanied by poor agricultural planning and restrictions on freedom of movement and trade, led to famine as a direct consequence.[xxxii] Given the limited capacity to cultivate food and RENAMO’s extraction of food resources, the majority of famine deaths occurred in RENAMO-held areas. Starvation was not by design, but it inevitably resulted from RENAMO’s policies to ensure population control.

In conclusion, the discrepancies in comprehensive, reliable data calls an updated estimate of total civilians killed into question. It is reasonable to posit that up to 100,00 civilians were killed.

Endings

By 1989, Mozambique’s national resources had been decimated or rendered useless as a consequence of the war’s destruction, multiple droughts, and on-going famine. With next to nothing left to support their operations, both RENAMO and FRELIMO became increasingly dependent on the material and financial capital funneled to them by external backers. It was the support derived from external intervention—a function of Cold War and apartheid politics—that propped up the two warring parties throughout the late 1980s and thus lengthened the duration of the conflict.[xxxiii] The turning point arrived when South African and covert American aid to RENAMO was curtailed after 1988, while Soviet, East German, and Zimbabwean assistance to FRELIMO tapered off between 1989 and 1991. These changes in regional and international support, coupled with new financial incentives and multi-lateral diplomatic initiatives, compelled RENAMO to gradually re-evaluate the cost of violence.

With the withdrawal of foreign funding, FRELIMO was the first to recognize that a military solution was no longer viable and initiated the first round of peace talks with RENAMO in 1989. FRELIMO further approved a new constitution permitting multi-party elections in 1990, signifying a drastic change in policy that appealed to RENAMO’s demand for, at minimum, a power-sharing agreement. Yet even as peace talks formalized[xxxiv] and progressed over the next two years with the facilitation of numerous diplomatic partners, RENAMO’s violent tactics continued. In July 1991, for example, 50 civilians were killed in the town of Lalua.[xxxv] Other estimates cite over fifty violations of an initial ceasefire agreement, with 445 civilian deaths between January and October 1991[xxxvi] and up to 1,000 over the course of the year.[xxxvii] The reasoning behind RENAMO’s stalling is not explicit, but the emerging role of financial payments in exchange for compliance in the peace process suggests that RENAMO leveraged its position to extract resources for as long as it could manage.[xxxviii]

From the beginning of the peace talks, “Tiny” Rowland, the CEO of a British-owned agricultural company in Mozambique, supplied unlimited funds to shuttle RENAMO to Rome and grease the wheels of negotiation. In addition to developing a trusted, personal relationship with Dhlakama, Rowland purchased RENAMO’s cooperation with $3 million in 1991 and $6 million in 1992.[xxxix] Likewise, the Italian government, as the host of the RENAMO and FRELIMO delegations in Rome, spent $20 million to accelerate the peace process, the majority of which was directed at RENAMO in payments and extravagant gifts. To illustrate this point, one Italian official related that “Dhlakama wanted a satellite telephone. We…made it clear that he would get it in return for signing one of the protocols. He came back several times to have a look at [the phone] before deciding to sign.”[xl] RENAMO had already practiced extortion extensively throughout the war, negotiating protection payments from private companies and the Malawi government. The peace process provided another avenue for such opportunistic behavior.

RENAMO’s continued use of violence lent credence to its threats to boycott the talks if its political and financial demands were not met. After 27 months of negotiations, however, a permanent ceasefire was established with the signing of the General Peace Accords on October 4, 1992. While Rowland and the Italian government are lauded for their role in ending the war, it is speculated that the financial payments may have actually served to delay peace at a cost to civilian life. In the absence of this cash flow, it is unlikely that RENAMO could have continued to operate given the dearth of resources on-the-ground.

Coding

We coded this case as ending primarily through strategic shift, with the withdrawal of international support for sides of the conflict, increasing stalemate in the armed conflict, and the influence of both domestic and international moderating forces. We further note that a nonstate actor was the primary perpetrator of atrocities.

Works Cited

Africa Watch. 1992. “Conspicuous Destruction: War, Famine and the Reform Process in Mozambique.” New York: Human Rights Watch, July.

DeRouen, Karl R. and Heo, Uk. 2007. Civil Wars of the World: Major Conflict Since World War II, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO.

Eck, Kristine and Lisa Hultman. 2007. “Violence Against Civilians in War,” Journal of Peace Research 44:2. Data available at http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/datasets/ucdp_one-sided_violence_dataset/.

Finnegan, William. 1992. A Complicated War: the Harrowing of Mozambique. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Gersony, Robert. 1988. “Summary of Mozambican Refugee Accounts of Principally Conflict-Related Experience in Mozambique,” Bureau for Refugee Programs, U.S. Department of State.

Leitenberg, Milton. 2006. “Deaths in Wars and Conflicts in the 20th Century,” Occasional Paper #29, Cornell University Peace Studies Program.

Minter, William. 1994. Apartheid’s Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique, London: Zed Books Ltd.

Patricio, Hipolito. 1991. “Mozambican Democracy Depends on Peace,” The Seattle Times, 12 September.

Rugumamu, Severine and Dr. Osman Gbla. 2003. “Studies in Reconstruction and Capacity Building in Post-Conflict Countries in Africa: Some Lessons of Experience from Mozambique,” The African Capacity Building Foundation.

Schneider, Gerald and Margit Bussmann. 2013. “Accounting for the Dynamics of One-Sided Violence: Introducing KOSVED,” Journal of Peace Research 50:5. Data available at http://www.polver.uni-konstanz.de/en/gschneider/research/kosved/.

Vines, Alex. 1998. “The Business of Peace: ‘Tiny’ Rowland, financial incentives and the Mozambican settlement.”Accord, Issue 3, 66 – 74.

Weinstein, Jeremy M. and Laudemiro Francisco. 2005. “The Civil War in Mozambique,” in Understanding Civil War, Volume 1, ed. By Paul Collier and Nicholas Sambanis, Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Notes

[i] Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 163-164.

[ii] Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 182.

[iii] With the fall of the white Rhodesian government, all financial, material, and intelligence support was terminated.

[iv] Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 165 and 170-171; Minter 1994, 174-175.

[v] Minter 1994, 49.

[vi] DeRouen and Uk 2007.

[vii] Gersony 1988, 18.

[viii] Weinstein 2005, 183

[ix] Africa Watch 1992, 191.

[x] Africa Watch 1992, 56.

[xi] Finnegan 1992.

[xii] Minter 1994, 192-193.

[xiii] Rugumamu and Gbla 2003, 10.

[xiv] Stathis Kalyvas, cited in Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 184-185.

[xv] Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 183.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid., 181-182.

[xviii] Schneider and Bussmann 2013.

[xix] Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 182.

[xx] Gersony 1988, 39.

[xxi] Africa Watch 1992, 41.

[xxii] Leitenberg 2006, 15.

[xxiii] Gersony1988.

[xxiv] Minter 1994, 266.

[xxv] Minter 1994, 206-216.

[xxvi] Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 182.

[xxvii] Schneider and Bussmann 2013.

[xxviii] Africa Watch 1992, 42.

[xxix] Schneider and Bussmann 2013.

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] Eck and Hultman 2007.

[xxxii] Africa Watch 1992, 114.

[xxxiii] Rugumamu and Gbla 2003, 24; Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 180-181; Minter 1994, 156-159.

[xxxiv] Formal peace talks began in Rome in July 1990. The first round of peace talks took place in August 1989 in Nairobi.

[xxxv] Patricio 1991.

[xxxvi] Africa Watch 1992, 37.

[xxxvii] Schneider and Bussmann 2013.

[xxxviii] Vines 1998, 74; Weinstein and Francisco 2005, 173-174.

[xxxix] Vines 1998, 73.

[xl] Ibid.