Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

In the aftermath of World War I, the 1919 May Fourth Movement resulted in heady national discussions about China’s weakness in a world of superpowered modern giants.[i] Moscow’s Communist International gave birth to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921, which embraced Marxism as a means of creating a stronger China.[ii] While the Soviet Union encouraged the CCP to join its sponsored Nationalist Party (KMT), the KMT turned on the CCP in 1927 as it physically and politically unified China, under authoritarian rule.[iii] Forced to flee, the CCP reconfigured itself into a rural, peasant- oriented revolutionary force, deploying guerrilla tactics.

While the KMT was preoccupied with the incredibly destructive Sino-Japanese War, internal dissent grew against the KMT when it failed to adequately resist the Japanese offensive, and in response to aggressive and exploitative KMT policies (both administrative and fiscal) such as adding taxes, monopolies and levies, while refusing to reform systems of local administration, communication, and credit.[iv] Japan was only finally defeated with the end of World War II in 1945.

The Chinese Civil War began in 1946, culminating in the victory of the CCP over the KMT in 1950, and was followed by a period of regime consolidation which ended with the initiation of the Great Leap Forward campaign in 1957. As the CCP captured territories during the Chinese Civil War, they immediately began enacting land reform, believed to be a crucial part of communist land collectivization.[v] The impoverishment of rural societies in parts of China coupled with the wartime dislocation and destruction also provided the CCP with a conducive ‘social laboratory for land reform’.[vi]

However, these new restrictive campaigns led to the collapse of traditional communal and interpersonal relationships.[vii] CCP work teams divided the local peasantry into class based categories, and initiated violence against those believed to be landlords or bourgeoisie by means of ritualistic public “struggle meetings.” These struggle meetings, and other means of exacerbating class conflict within villages, sometimes produced mob violence and collective killings.

Atrocities, 1947 – 1953

Several dynamics contributed to widespread use of violence between 1947 and 1953. The CCP embarked on a program of regime consolidation, simultaneously using paternalist policies towards those that the CCP deemed to be within the ‘revolutionary fold’, and terror against those deemed as opponents of the revolution. State coercion was used to implement both sets of policies, with ‘drives’ or social movements intended to mobilize popular support for these initiatives of regime consolidation and more generally, for the CCP.[viii]

Each of these initiatives targeted a particular social group, isolating it from the rest of society, eliminating ‘undesirable’ section of it, and reintegrating it into Chinese society on the terms of the CCP. The land reform campaign targeted landlords; the ‘Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries’ targeted counterrevolutionaries; the ‘Three-Antis Campaign’ targeted corrupt bureaucrats; and the ‘Five Antis Campaign’ targeted capitalists and private entrepreneurs. [ix] It is worth noting that although these campaigns were distinct in terms of intent, that is, in terms of the category of population targeted by the CCP-State as being key political, social or economic competitors, there were spatial and temporal overlaps.[x] Further, with the backdrop of the Korean War (1950 – 1953), capital punishment was used by the CCP explicitly as a tool of mass mobilization and state building.[xi]

CCP land reform began first in Northern China, where the CCP had its power base. Northern China had been badly affected by the ecological degradation during WWII, and speculative land dealings had become rampant in the period immediately following the war’s end.[xii] There seems to have been some support for land reform among peasantry in the North (especially among peasants who viewed exploitation and injustice as having increased during the war), but in many areas, the majority of peasants remained ambivalent.[xiii]

The more commercialized countryside in parts of Southern China followed a slightly different pattern. While some research suggests that initially, there were landlords and ‘bourgeoisie’ and certainly, ‘local strongmen’ amongst the Chinese peasantry, they were more prevalent in the north. In the South, the CCP found that categories of bourgeoisie, landlord and peasant did not apply as cleanly, and consequently, CCP authorization for local officials to use violence as part of seizing and consolidating power resulted in often-arbitrary executions between 1947 to 1952.[xiv]

Pushback by the rural peasantry occasionally escalated into guerrilla warfare, killing communist work teams and deeply alarming Mao. Other villages peacefully resisted the violence by pretending to have already purged their landlords and bourgeoisie before work teams arrived. Within the CCP there was disagreement as to the effect of the land reform – some conceded that the strategy had led to too many deaths (in turn, alienating the populace), whereas others argued that the terror had ‘pacified’ the countryside.[xv]

In December 1950, a few months after the official founding of the People’s Republic of China, the CCP began focusing on the liquidation of counter-revolutionaries, the “Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries,” which was preceded by action against various lay-Buddhist sects, such as the Unity sect, which the CCP classified as ‘attacks on secret societies and superstitious sects’.[xvi] Mao dictated quotas of the number of people to be killed per province based on arbitrary assumptions of how many counter-revolutionaries were thought to reside in each province. The amount of killings was sometimes pushed past the quotas by local administrators who saw the counter-revolutionary extermination program as a means to eliminate all potential political rivals.[xvii]

Violence narrowed during the “Three Antis Campaign” from October 1951 to June 1952 as the CCP attempted to end the three evils of corruption, waste, and bureaucracy. Mao once again handed down quotas for the number of people to be executed. So-called “Tiger-Hunting Teams” used the techniques of the land reform campaign to target and isolate victims. The Campaign then refocused on the private sector, targeting the five evils of bribery, theft of state property, tax evasion, cheating on government contracts, and stealing state economic information as part of the new “Five Antis Campaign.” However these campaigns used the tools of ‘mass criticism, thought reform, internal exile, loss of positions and lengthy jail sentences’ rather than capital punishment.[xviii]

By the end of the Korean War in 1953, the CCP had returned the Chinese economy to stability from its earlier free fall under the KMT, and initiated its first Soviet-style Five-Year Plan of rapid industrialization. While the Plan was an astonishing economic success, Mao was still displeased with the amount of progress made, and, in 1957, created the Hundred Flowers Campaign, encouraging criticism of the CCP. After only a month, more than three hundred thousand were then punished for their critiques.[xix]

On the whole, the People’s War of Liberation can be characterized as a top-down Party-State campaign, consistently executed at the national, provincial, and local levels, specifically aimed at the creation of a vertically integrated, centralized state and the establishment of socialism in China.

With Mao having thus demonstrated and consolidated his political power, party leaders were no longer willing to stop him from implementing his vision of a fully communist China by means of his most massive collectivization and industrialization campaign yet: the Great Leap Forward (1958 – 1961, discussed in a separate case study).[xx]

Fatalities

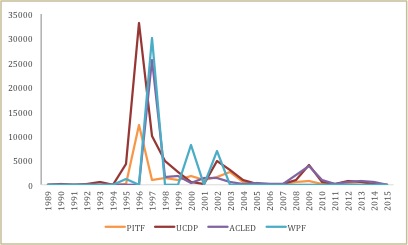

Research suggests a rough estimate of 3.5 million fatalities.

The collection of statistics in the early years of the campaign was inconsistent and categories of classification were ambiguous. In sub-urban areas or peri-urban spaces, targets of the land reform campaign and the Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries may have been lumped together, and therefore reported to different bureaucratic apparatus – for example, south of the Yangtze, where these campaigns ran concurrently, and may also have included ‘local bullies’ who were targets for both campaigns.[xxi]

Land reform campaign (1947- 1952): Some authors estimate this figure to be in the range of roughly 1.5 – 2 million.[xxii]

Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries (1950 – 1953): Roughly 2 million.[xxiii]

Together, the casualties in the two campaigns may have ranged between a low estimate of one million to a high estimate of five million (where people were either sentenced to death by the state or killed in the highly charged atmosphere of public accusations).[xxiv] Kuisong reports that the low state estimate of 700,000 people killed comes from a report submitted by Xu Zirong, Deputy Public Security Minister, in January 1954, which states that 712,000 people were killed.[xxv] The CCP congress in September 1956 mentioned that 800,000 were killed in the violence, while Bo Yibo (then a member of China’s State Planning Commission) mentioned that 2 million people had been killed, in a work report in 1952. [xxvi] Domes himself estimated that 3 million were killed between these two campaigns.[xxvii]

Three Antis and Five Antis campaign (1951 – 1952): Uncertain; fatalities seem to have been low, as other tools of punishment were preferred.

Endings

Each campaign’s atrocities ended under unique circumstances. In general, if the successive waves of campaigns are understood as an effort at regime consolidation, then after the end of the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, there was no further need for the CCP to use violence and coercion in ways similar to the former campaigns.

Land requisitioning and reform ended with the completion of the campaign: all land had been apportioned and all villages had been targeted and purged by CCP work teams. The matter would be taken up once more with gradual attempts at collectivization beginning in 1953, eventually leading to the Socialist High Tide and the Great Leap Forward. However, reactions to land reform may have led to further violence during the Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries. The Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries deescalated as the government recognized that the campaigns’ killings had accelerated past its quotas. Around mid-April 1951, provincial officials, fearing the emergence of guerrilla counter-revolutionaries as had occurred during the land reform campaign, attempted to suspend the campaigns.

Instead, killings accelerated as local officials worked to kill as many people as possible before they would be forced to stop. An alarmed Mao called a national public security conference in May of 1951 to begin deescalating the campaign, and issued specific criteria for executions.[xxviii] The central government’s concern may have been in reaction to the acquisition of the power to kill by local officials, as opposed to its centralization in the state. However, the Campaign continued for years after, with the occasional flare-up of executions of counter-revolutionaries occurring from time to time from late 1951 to mid-1952. Reports of campaign-related persecution persisted into 1953. However, the requirement of approval for executions from higher-up in the Party-State hierarchy prevented the outbreak of the same kind of intensity of violence.

The focus on the new anti-corruption Three/Five Antis Campaigns also resulted in a drop in executions.[xxix] While its methods continued to cause social and economic chaos, it did not contain the same kind of systems of mass killing such as land reform’s work crews and the Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries’ killing quotas. Mao was more concerned, as always, with class struggle, and the Anti Campaign not only pushed the capitalists out of the country, but also allowed the state to assume control of their wealth and enterprises.[xxx]

In the years after the most intense campaigns of the War of Liberation, he worked to push agricultural collectivization via the Socialist High Tide campaign, improve the Party via the Hundred Flowers Campaign, and persecute critique via the Anti-Rightist Campaign. While persecution continued, Mao and the Party seemed content to simply push dissenters into labor camps rather than engage in the kind of mass killing that characterized the beginnings of the War of Liberation.

Coding

This is one of our rare cases where the violence was carried out as planned, but where the primary perpetrator began the atrocity period as a non-state actor, but continued to commit atrocities after it had gained power. The primary cause of ending was that the Communist regime deemed it had sufficiently established control and implemented policies to decrease violence thereafter. We also code for popular violence, to account for the involvement of average Chinese villagers in the perpetration of violence at certain phases.

Works Cited

Dikötter, Frank. 2013. The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-57. New York: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Domes, Jurgen. 1973. The Internal Politics of China, 1949-1972. New York: Praeger.

Hung, Chang-tai. 2010. “The Anti-Unity Sect Campaign and Mass Mobilization in the Early People’s Republic of China.” The China Quarterly 202: 400-420.

Hutchings, Graham. 2001. Modern China: A Guide to a Century of Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Kuisong, Yang. 2008. “”Reconsidering the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries.” .” The China Quarterly 193 (2008): 102-121 n. pag.

Lieberthal, Kenneth. 1980. Revolution and Tradition in Tientsin, 1949-1952. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Miao, Michelle. 2013. “Capital punishment in China: A populist instrument of social governance,” Theoretical Criminology 17(2): 233-250.

Muscolino, Micah. 2015. The Ecology of War in China: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938-1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ning, Zhang. 2008. “The political origins of death penalty exceptionalism: Mao Zedong and the practice of capital punishment in contemporary China.” Punishment and Society 10(2): 117-136.

Schoppa, R. Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia University Press.

Strauss, Julia. 2002. “Paternalist Terror: The Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries and Regime Consolidation in the People’s Republic of China, 1950-53.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 44(1): 80-105.

Strauss, Julia . 2006. “Morality, Coercion and State Building by Campaign in the Early PRC: Regime Consolidation and After, 1949-1956,” The China Quarterly 188.

Strauss, Julia. 2006. “Morality, Coercion and State Building by Campaign in the Early PRC: Regime Consolidation and After, 1949-1956,” The China Quarterly 188: 891-912.

Walker, Richard L. 1955. China under Communism: The First Five Years. New Haven: Yale University press.

Westad, Odd Arne. 2003. Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946-1950. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Notes

[i] Hutchings 2001, 306.

[ii] Hutchings 2001, 65.

[iii] Hutchings 2001, 256.

[iv] Westad 2003, 12.

[v] Schoppa 2000, 107.

[vi] Westad 2003, 7.

[vii] Schoppa 2000, 107.

[viii] Walker 1955, 77.

[ix] Strauss 2002, 81.

[x] Strauss 2006, 900.

[xi] “Over 30,000 people attended an ‘accusation rally’ held at a sports stadium in Shenyang while approximately 1.12 million people listened to its live radio broadcast. Another 30,000 participated in an ‘accusation rally’ in Guangzhou, while over 70,000 people listened to its radio broadcast; and over 10,000 people attended a similar sentencing rally in Shanghai, while nearly 3 million listened to the radio broadcast.” See Miao 2013, 235-6 and Ning 2008.

[xii] Muscolino 2015.

[xiii] Westad 2003, 107-108.

[xiv] Strauss 2006, 902.

[xv] Westad 2003, 128-135.

[xvi] Hung 2010, 400.

[xvii] Kuisong 2008, 115.

[xviii] Strauss 2006, 902.

[xix] Schoppa 2000, 110.

[xx] Dikötter, The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-57, 295.

[xxi] Strauss, “Morality, Coercion and State Building,” 901.

[xxii] Dikötter 2013, 83.

[xxiii] Dikötter 2013, 100.

[xxiv] Strauss 2006, 901. See also Lieberthal 1980, 108.

[xxv] Kuisong 2008, 120.

[xxvi] Cited in Domes 1973, 52.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Kuisong 2008, 117-8.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Dikötter 2013, 165-166.