Introduction | Atrocities | Fatalities | Ending | Coding | Works Cited | Notes

Introduction

By the 1970s, El Salvador’s government, ruled since 1948 by a series of military presidents, faced both internal armed and political opposition. The contestation between the government and the armed opposition escalated to civil war from 1979 – 1992. We focus on two periods of the conflict that resulted in the highest levels of violence against civilians: 1979 – 1981, which can be characterized as indiscriminate, state-sponsored violence; and 1981 – 1984, a period of increasingly conventional war, when the numbers of civilians killed began to decline but remained above the threshold for this study.

Atrocities

On October 15, 1979, a coup by moderate military officers ousted dictator Carlos Humberto Romero and formed the Revolutionary Junta Government (JRG).[i] Among the arguments for the coup were issues of more equitable development, human rights and democratization, and initially the new regime included several civilians. However, shortly afterwards, right-wing elements within the military and security forces began asserting power. What followed was a systematic campaign of government terror against all governmental opposition (political and armed), which included death-squads and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, particularly in rural areas.

Among the most notable incidents of this phase was the assassination of human rights advocate Monsignor Oscar Romero, who was shot dead by a sniper while conducting mass in March 1980. During his funeral, a bomb was set off. State armed forces responded by opening fire on the assembled crowd, killing approximately 30 people and wounding 200 more. Major Roberto D’Aubisson, who was strongly implicated in organizing and financing the death squads responsible for assassinating Romero, was arrested but soon released by the government. In the Fall of 1980, the primary leftist guerrilla groups joined to form the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN).[ii]

The government’s counter-insurgency operations subjected the rural civilian population to indiscriminate violence, mass displacement, and death squads. There were many incidents of dumping of bodies in mass graves, including several well-documented massacres of unarmed peasants in 1981 and 1982.[iii] The state’s use of indiscriminate violence fueled the guerrilla insurgency, whose capacity grew to rival that of the military. The country entered a full-blown civil war between the FMLN and the military regime.[iv]

The government of El Salvador lost ground militarily. At the same time, it began to lose American support, as the U.S. Congress imposed restrictions on direct military aid due to the country’s human rights record. In December 1983, U.S. President Ronald Reagan , sent US Vice-President Bush to El Salvador and warning of more decreases in US aid if murders continued and death squad leaders were left unpunished.[v] Subsequently the activities of the death squads and major rural massacres declined, although there is some discrepancy in the data on precisely when the decline begins.[vi] Further, the country’s first democratic election in several decades were held in 1984, with centrist Jose Napoleon Duarte who had promised to usher in political and socioeconomic reforms, winning the presidency — the first civilian President in over 50 years.

During the period 1984 – 1985, the war shifted from a more conventional confrontation between well-matched sides, to the government increasingly winning the direct confrontations and the FMLN increasingly adopting guerrilla tactics.[vii] Due to continuing violence, the number of Salvadoran refugees and IDPs rose to 1.5 million by 1984. During this period, the killing of civilians remained high with estimates in the thousands per year (see below) amidst a wide range of other human rights abuses.

However, following the 1984 election, US Congress approved a massive increase in military support to El Salvador. With this aid, following a lull in bombing during early 1984,[viii] the military’s position steadily improved. In the second half of 1984, as US support amped up, the government was able to diminish the threat posed by FMLN in direct confrontations. The FMLN shifted its campaigns to destroying economic targets, deploying landmines, and murdering and hostage-taking of government officials. The government conducted aerial bombing campaigns to drive civilians away from sections of the country controlled by guerrilla groups. These bombing campaigns, while often indiscriminate and at times specifically targeted civilians, began to drop off by the year’s end.[ix] By 1985, the insurgents returned to more classic guerrilla techniques: limited attacks against economic and military facilities, mines, booby traps and sniping.[x] While many described the war as reaching a stalemate during the later 1980s, the lethal impact for civilians was reduced as the patterns of conflict shifted.

A final spike in violence occurred in relation to the FMLN’s offensive in the capital, San Salvador, and several major cities on November 11, 1989. This action and the government’s response cost approximately 2,000 lives over the subsequent months. A state of emergency was declared and against this backdrop army units dragged from their beds and gratuitously murdered six Jesuit priests and their housekeeper and her 15-year old daughter. This shocked the international community, including the US government, which cut military aid in 1990.

The horror of this incident coincided with several other factors to increase the push for a mediated peace process: the parties accepted that they were not capable of a definitive military victory. Further, the end of the Cold War reduced outside support for military solutions (including U.S. support for the government), and momentum shifted towards political moderation on both sides in El Salvador.[xi] Together, these factors enabled a UN-mediated peace negotiation process to take place.[xii] A ceasefire was called on December 31, 1991, and on January 16, 1992, the final peace accords were signed in Mexico City, putting an end to the 12-year conflict. The FMLN transitioned into a legitimate political party and a general amnesty law was signed in 1993.[xiii]

A Truth Commission (TC) was established in July 1992[xiv], and found that 85% of “serious acts of violence” were attributed to the state. Over 60% of these incidents concerned extrajudicial executions, over 25% concerned enforced disappearances, and over 20% included complaints of torture.[xv] Over 75% of the serious acts of state violence reported to the TC took place during 1980-1984. The violence was less indiscriminate in urban areas during all years, and in rural areas after 1983. 95% of complaints to the TC concerned incidents in rural areas and 5% per cent concerned incidents in more urban areas.[xvi] Although violence generally declined after 1983, and multiple sources of data agree on a decrease in lethal violence by 1985, a later smaller yet still significant spike occurred in 1989.[xvii]

Violence attributed to the FMLN occurred mainly in conflict zones where the FMLN had firm military control. Nearly half the complaints against FMLN concern deaths, mostly extrajudicial executions. The rest relate to enforced disappearances and forcible recruitment.[xviii] As government violence began to drop off after 1983, civilian deaths caused by guerrilla forces increased in the second half of the 1980s, but at no pointed approximated the scale of government killing. This is in part the result of guerrilla tactics that shifted towards heavier use of mines in 1985 and 1986. Civilian deaths caused by guerrilla landmines increased throughout the second half of the 1980s and were in the double or triple digits.[xix]

Fatalities

Commonly cited overall civilian death estimates for the duration of the civil war range from 30,000 –70,000. Stanley estimates 50,000 civilians killed between 1978 and 1991, with 42,171 killed during the peak years of 1978-1983.[xx] In 1988, the OAS estimated 60,000 people had been killed,[xxi] and in 1990 increased this toll to 63,000.[xxii] While the OAS generally reports on civilian rather than combatant deaths, it is not explicitly stated whether these figures include only civilian deaths, or civilian and combatant.

Much of the best data on civilian deaths during the atrocity period was recorded by religious and human rights organizations working in El Salvador, including Tutela Legal and Socorro Juridico Cristiano, whose numbers place the number of civilian deaths closer to 50,000.[xxiii] However, given the significant difficulty of documenting deaths that occurred in rural areas, where the majority of killing occurred, the higher estimates are not unreasonable. However, it is also possible that the numbers of civilian deaths recorded by human rights and religious organizations do not in fact, reflect only civilians, and that some guerrillas are included in these larger figures.

1980: Credible numbers of civilian deaths for this year range from 9,826 from the Center for Documentation and Information[xxiv] to close to 12,000.

1981: Estimates ranging from 12,501(Christian Legal Aid)[xxv] to 16,266 as recorded by the Human Rights Commission of El Salvador.[xxvi]

1982: Civilians were killed at a rate of 300 to 500 people per month in 1982.[xxvii] The lowest figure is 2,330 civilians (US embassy). The Archbishop Oscar Romero Christian Legal Aid Office reported 5,962 civilian deaths, with 3,059 political murders occurring in the first eight months of the year, and nearly all of these murders the result of action by Government agents against civilians not involved in military combat. According to Socorro Juridico Cristiano,[xxviii] there were over 5,000 deaths this year.

1983: Monsignor Gregorio Rosas Chavez reported 6,096 deaths: 4,700 people killed by army and death squads, and 1,300 members of the armed forces killed.[xxix] Over 5,000 civilians according to Socorro Juridico Cristiano.[xxx] According to Tutela Legal,[xxxi] 5,209 civilians were killed and another 578 unresolved abductions.

1984: 1,965 in first eight months of 1984, according to Legal Aid.[xxxii]

1985: approx. 2,000 according to the TRC. 1,655 non-combatant civilian deaths according to Christian Legal Aid.[xxxiii]

1986: In a six month period from January to June 1986, the Organization of American States (OAS) reported 36 civilian death caused by armed forces, 2 killed during military operations, 3 killed during bombardments, 36 killed by mines, 24 killed by death squads and 52 civilians arrested and missing, for a total of 101 killed and 52 missing.[xxxiv]

1987: The OAS reported 24 political murders attributed to death squads, 60 deaths caused by government armed forces, and 29 deaths perpetrated by guerillas.[xxxv]

1988: Reported resumption of mass executions and death squad killings. Death squad killings averaged 8 people murdered per month. More than 150 people were believed to have been killed by mines.[xxxvi] OAS reported 32 political murders attributed to death squads, 48 deaths caused by government armed forces, and 19 deaths perpetrated by guerillas.

1989: FMLN launched their largest offensive of the conflict. FMLN sheltered in civilian and urban areas, prompting indiscriminate aerial bombardment of these areas by the government. The government stepped up arrests, torture, disappearance, and murder of non-combatants in this period. According to the TRC, civilian deaths likely numbered in the hundreds.[xxxvii] The OAS reports heavy bombing of the civilian population, with 2,400 deaths in November and December alone, alongside systematic acts of intimidation and detention and a marked increase in torture. While OAS does not explicitly state whether this death toll includes combatants, all specific examples of violence given in the report are of civilian deaths.[xxxviii] This larger figure is supported by the Salvadoran Human Rights Commission, which reported 2,868 civilians were killed between May of 1989 and May of 1990.[xxxix]

1990: 852 deaths (unknown how many were guerilla and how many were civilians).[xl]

Summarizing the above figures, nearly 40,000 civilian deaths were specifically reported and recorded by religious and human rights agencies between 1980 and 1985, with a slightly larger number killed in the longer period of instability. We nonetheless include this case, given potential gaps in the data and our preference to err on the side of inclusion.

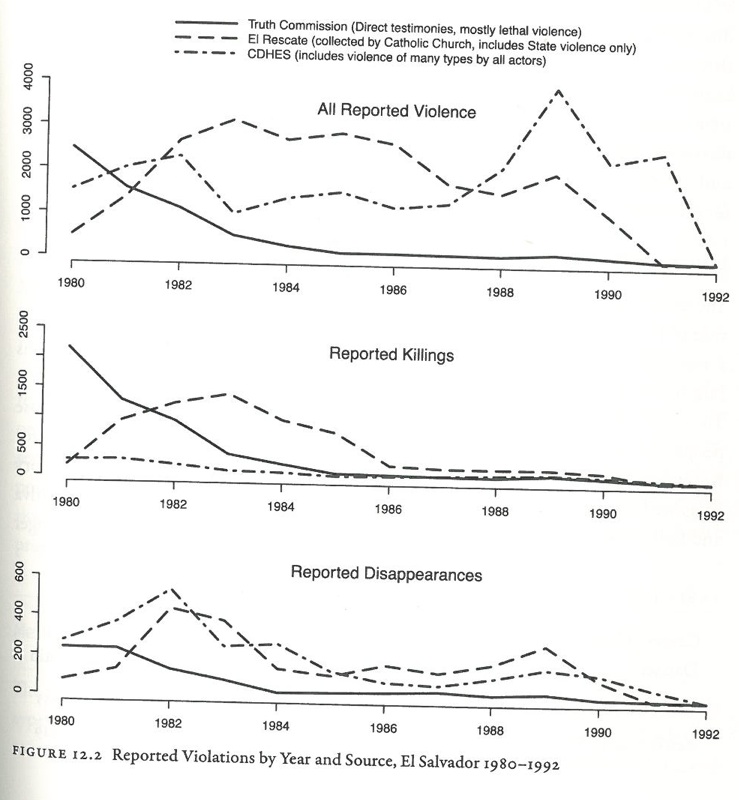

A comparative study of three sources of conflict data, the UN-sponsored Truth Commission, non-governmental Human Rights Commission of El Salvador (CDHES), and the NGO El Rescate (sources from Catholic Church, only include state violence, not insurgent) finds remarkably different pictures emerge from the different data sets.[xli] When the authors of the study disaggregated killing from all reported violence, the disparities lessen a little; clearly all three sources agree that lethal violence was highest at the beginning of the conflict. However, there remain differences in dating both the peak of the spike and the timing of the decline. We therefore accept as the end date 1985—this is the point at which there is agreement that killing (and disappearances, often result in killing) declined precipitously. Further, by the albeit extremely incomplete annual totals we were able to document, above, it also seems to mark a shift from figures in the thousands to figures just over 100, a decline of significant scale. We note, however, that other forms of violence continued and spiked at later points in the conflict.

Chart from: Kruger, Jule, Patrick Ball, Megan E. Price, and Amelia Hoover Green. 2014. “It Doesn’t Add Up: Methodological and Policy Implications of Conflicting Causality Data” in Counting Civilian Casualties: An Introduction to Recording and Estimating Nonmilitary Deaths in Conflict, eds. Taylor B. Seybolt, Jay D. Aronson, and Baruch Fischhoff (Oxford University Press, 257.

Ending

We mark the end of the atrocities period in 1985. The decrease in civilian deaths appears to be partly the result of international pressure (mostly from the U.S.) to curb violence against civilians, especially the government’s use of death squads,, and partly due to patterns in the armed conflict which ultimately resulted in the government winning an incomplete victory in the conventional warfare, before the insurgents shifted to limited, asymmetrical guerrilla warfare.

The guerrilla conflict continued for some years thereafter until a mediated peace process engaged all actors. As Maragarita S. Studemeister summarizes:

Under the auspices of the United Nations, twenty months of negotiations and a series of partial settlements between the government of El Salvador and the rebel Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) culminated January 16, 1992 in the signing of the Chapultepec Peace Accords in Mexico City. The implementation of the accords initiated a transition from war to peace and profoundly transformed political life in El Salvador.[xlii]

Coding

We coded this case as ending through strategic shift away from directly targeting civilians, influenced by both international and domestic actors. We included the leadership change that resulted from the 1984 elections

Works Cited

Bonnier, Raymond . 1982. “Reagan’s Salvador Rights Report: The Balance Sheet,” The New York Times, February 26.

Byrne, Hugh. 1996. El Salvador’s Civil War: A Study of Revolution. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 1990. El Salvador Armed Forces: Human Rights Abuses, 1 December. Accessed 23 April. Available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6a80d14.html

Commission on the Truth for El Salvador. 1993. “From Madness to Hope: the 12-year war in El Salvador: Report of the Commission on the Truth for El Salvador.” March 15. Available at: http://www.usip.org/publications/truth-commission-el-salvador

Kruger, Julie, Patrick Ball, Megan E. Price, and Amelia Hoover Green. 2014. “It Doesn’t Add Up: Methodological and Policy Implications of Conflicting Causality Data” in Counting Civilian Casualties: An Introduction to Recording and Estimating Nonmilitary Deaths in Conflict, eds. Taylor B. Seybolt, Jay D. Aronson, and Baruch Fischhoff (Oxford University Press). 247 – 264, 257.

Montgomery, Tommie Sue. 1995. Revolution in El Salvador: From Civil Strife to Civil Peace, 2nd ed. Boulder: Westview Press.

OAS-IACHR. 1986. “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1985-1986.” 26 September. Available at: http://www.cidh.org/annualrep/85.86eng/toc.htm

OAS-IACHR. 1988. “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1987-1988.”16 September. Available at: http://www.cidh.org/annualrep/87.88eng/TOC.htm

OAS-IACHR. 1990. “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1989-1990”. 17 May. Available at: http://www.cidh.org/annualrep/89.90eng/TOC.htm

Peceny, Mark and William D. Stanley. 2010. “Counterinsurgency in El Salvador.” Politics & Society 38(1): 67 – 94.

Stanley, William. 1996. The Protection Racket State: Elite Politics, Military Extortion, and Civil War in El Salvador. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

ed. Studemeister, Margarita S. 2001. “El Salvador Implementation of the Peace Accords,” USIP: Peaceworks No. 38. January. Available at: https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/pwks38.pdf

Notes

[i] Montgomery 1995, 75.

[ii] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993, 29.

[iii] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993, 27.

[iv] Byrne, El Salvador’s Civil War, 69.

[v] “Report of the UN Truth Commission on El Salvador,” 31.

[vi] Montgomery 1995, 177.

[vii] Peceny and Stanley 2010.

[viii] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993

[ix] Peceny and Staney, 81.

[x] Peceny and Stanley, 80.

[xi] Stanley, 240-242 and 252-253.

[xii] Ibid., 39.

[xiii] Montgomery 1995, 225.

[xiv] The TC’s mandate was to document violence beginning in 1980, which is troubling, considering how high the spike is in 1980. It begs the question of whether this accurately describes a sudden, enormous spike of violence in 1980, or how much violence occurred before this date.

[xv] Ibid., 43.

[xvi] Ibid., 44.

[xvii] OAS-IACHR, “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1989-1990”.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] America’s Watch, 64-65.

[xx] Stanley, 1 and 3.

[xxi] OAS-IACHR, “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1987-1988.”

[xxii] OAS-IACHR, “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1989-1990.”

[xxiii] William Stanley, The Protection Racket State: Elite Politics, Military Extortion, and Civil War in El Salvador (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1996), 281.

[xxiv] Bonnier.

[xxv] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993, 30.

[xxvi] Bonnier.

[xxvii] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993, 202.

[xxviii] Stanley, 281.

[xxix] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993,34.

[xxx] Stanley, 281.

[xxxi] Stanley, 64.

[xxxii] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993, 35.

[xxxiii] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993, 36.

[xxxiv] OAS-IACHR, “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1985-1986.”

[xxxv] OAS-IACHR, “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1987-1988.”

[xxxvi] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993, 38.

[xxxvii] Commission on the Truth for El Salvador 1993, 39.

[xxxviii] OAS-IACHR, “Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1989-1990”.

[xxxix] Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, El Salvador Armed Forces: Human Rights Abuses, 1 December 1990. Accessed 23 April 2015. Available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6a80d14.html

[xl] “Report of the UN Truth Commission on El Salvador,” 30 – 40. All figures and terminology taken directly from the report, which does not use consistently disaggregate civilians, guerilla and state armed forces deaths, nor define the difference, if any, between “deaths” and “political murders.”

[xli] Kruger, Jule, Patrick Ball, Megan E. Price, and Amelia Hoover Green. 2014. “It Doesn’t Add Up: Methodological and Policy Implications of Conflicting Causality Data” in Counting Civilian Casualties: An Introduction to Recording and Estimating Nonmilitary Deaths in Conflict, eds. Taylor B. Seybolt, Jay D. Aronson, and Baruch Fischhoff (Oxford University Press). 247 – 264, 257.

[xlii]ed. Studemeister, Margarita S. 2001. “El Salvador Implementation of the Peace Accords,” USIP: Peaceworks No. 38. January 2001, 5.