by Thomas Hershewe, Zoe Kava, and Brian Schaffner

Conservatives are happier and have better mental health than liberals, or at least that’s what surveys show. In a previous post, we concluded that conservatives rate their mental health higher than liberals, moderates, and the population as a whole; this mental health divide still persists even after controlling for a variety of other factors that may influence one’s mental health–like age, religion, marital status, and significant recent life events. At the same time, we wondered if conservatives were rating their mental health higher simply because they take the notion of “mental health” less seriously in the first place. Given stigma surrounding mental health, we suggested that conservatives may be dismissive of the term “mental health” and report a higher rating as a result. Thus, while conservatives appear to be happier than liberals, it is not clear whether this reflects a true difference, or is a result of how seriously each group takes the term “mental health.”

To test this possibility, we designed an experiment that would allow us to see whether conservatives were inflating their self-assessments when asked about their mental health on a survey. Using a 2023 Cooperative Elections Study team module that included interviews with 1,000 American adults, we included the same question that we analyzed in our previous post: “Would you say that in general your mental health is…” with five responses ranging from poor (which we assign a score of 0) to excellent (a score of 100). However, this time we only gave half of the sample that version of the question while the other half saw the identical question except exchanging the term “mental health” for “overall mood”.

Mood and mental health both encompass one’s emotional, psychological, and overall well-being. Research finds that the two are positively related: having a good mood is strongly associated with having better mental health. Commonly, mental health examinations ask about one’s mood, among other factors that might relate to mental health such as how someone is thinking, sleeping, or eating. While the concept of mental health is broader than mood, for our purposes we believe both terms provide a reflection of a respondent’s general mental well-being.

When we ask respondents to rate their mental health, the average conservative falls slightly below the “very good” point in the scale with a score of about 70 out of 100. For comparison, liberals, moderates, and the sample as a whole all report mental health ratings just above “good” with scores ranging from 60-65. In other words, there is about a 10 percentage point gap between how conservatives and liberals rate their mental health. About two-thirds of conservatives say that they have “excellent” or “very good” mental health, while the same is true for just 53% of liberals.

Conversely, when asking about overall mood, liberals and conservatives report almost identical ratings – also just above “good” at around 61 out of 100. With the mood term, the percentage of conservatives selecting the “excellent” or “very good” category drops considerably, to just 48%, comparable to the share of liberals selecting those two categories (52%).

Mental health and mood are not perfect synonyms. However, if conservatives were genuinely happier than liberals then we would expect them to also report higher ratings for their overall mood. Notably, only conservatives produce answers that are significantly different when the mood language is used rather than the mental health terminology. Liberals and moderates have very similar average ratings in responses to the question when it was about overall mood rather than mental health.

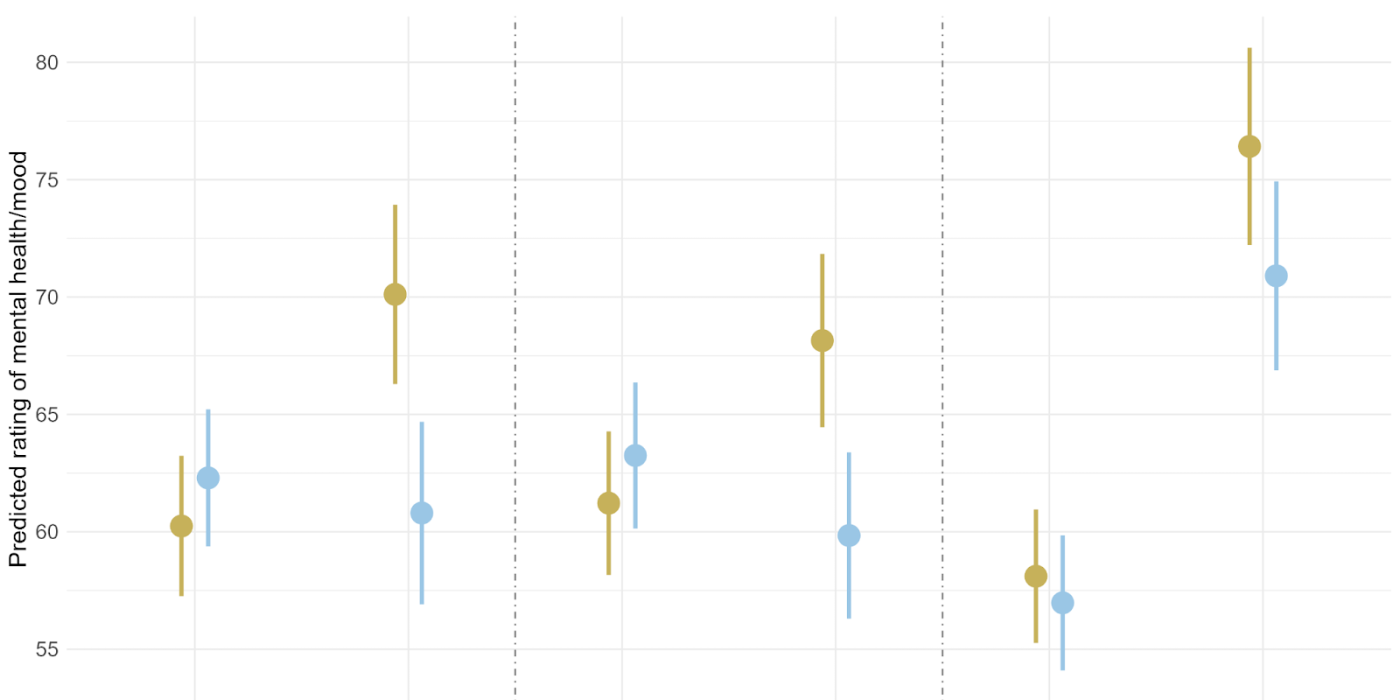

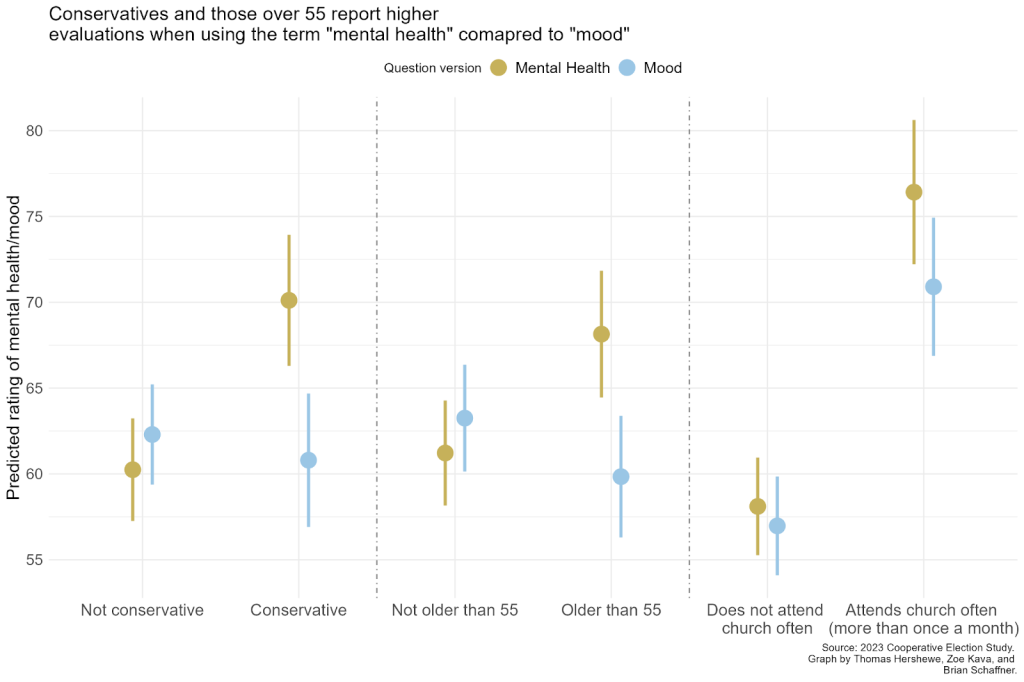

So why do conservatives respond differently to the language about overall mood? It may not be about conservatism per se. After all, there are other strong predictors of positive mental health ratings which we showed in our previous work; two of the strongest were old age and church attendance. Both of these factors are correlated with conservatism, so it may be the case that it is actually just that older people or frequent church attenders respond differently to the overall mood term compared to the mental health terminology. To test this possibility, we estimated a regression model allowing us to simultaneously test each of these three explanations – that responding differently to the mood terminology is about conservatism, old age, or frequent church attendance.

Even controlling for old age and church attendance, it is clear that conservatives are rating their mental health more positively than their mood – and this is not the case for non-conservatives. In fact, there is basically no difference in how non-conservatives rate their mental health versus their mood. Furthermore, conservatives rate their mood about the same as non-conservatives do. It is only when the term “mental health” is used that we see a significant gap emerge.

Sensitivity to the wording of the question is not just limited to conservatism; the wording change has a similar effect on those over the age of 55. This is not surprising since there is also stigma and misunderstanding surrounding the term “mental health” in older populations. But our model indicates that conservatives rate their mood lower than their mental health even after controlling for age. Interestingly, we do not see a similar pattern for frequent church attenders. People who attend church frequently rate their mental health more positively than those who do not, but these frequent church attenders also rate their mood higher as well. The positive effect of church attendance is robust to the terminology used in the question.

So, do conservatives have better mental health than liberals? It would appear not. Something else is going on. The stigma surrounding mental health among conservatives and older citizens is likely inflating these groups’ evaluations of their own mental health. Conservatives and those over the age of 55 report significantly more positive evaluations when asked about their mental health compared to their overall mood.

Older people may hold negative views about mental health brought about by stigmas that existed when they were growing up. Older generations grew up with less mental health awareness, and oftentimes mental illnesses were looked down upon. Conservatives may also view mental illness as a sign of weakness. One study found that conservatives were more likely to hold stigmatized views of people with mental illnesses. Thus, in describing their own mental health, conservatives might want to reinforce this separation between themselves and those with mental illnesses. When the prevailing narrative among one’s community or social network portrays mental health struggles as indicative of weakness rather than something that needs to be helped, it makes sense that older people and conservatives would want to downplay their own mental health struggles. Rather than reflect a genuine difference, it appears that the ideological “mental health gap” is driven, at least in part if not entirely, by stigma surrounding the term among those on the right.