Home > Off the Charts > Big Tech’s Opportunity for Inclusive Growth

Big Tech’s Opportunity for Inclusive Growth

The work from home experiences from the pandemic could serve as a catalyst for the tech industry to narrow its large disparities in geographic and demographic diversity, if it chooses to take those lessons to heart.

Summary

Pandemic-induced work-from-home policies—now slated to be in place for most of 2021, if not indefinitely—could serve as a catalyst for the tech industry to narrow its growing regional and demographic disparity; allowing more cities and demographics to contribute to and prosper from the industry’s economic growth potential. We examined this issue using metrics such as digital readiness, cost of living, and diversity of tech talent pools for a group of states and major cities in the US to assess whether pandemic-induced work-from-home policies could offer the industry an inclusive path to growth.

Key Observations and Insights

When we think of tech hubs in America, the usual suspects come to mind: San Francisco, San Diego, San Jose, Seattle, and Boston—90% percent of the tech job growth between 2005 and 2017 was concentrated in just these five cities. This extreme geographic clustering of high-wage jobs has led to problems such as soaring home prices and the concentration of college-educated tech talent in a handful of “superstar” cities. Further, the well-documented prevalence in the US tech sector of homophily and a reliance on personal relationships and “culture fit” to grant access and work opportunities creates self-perpetuating network effects that weigh heavily against under-represented groups such as women, Black people, and Latinx people.

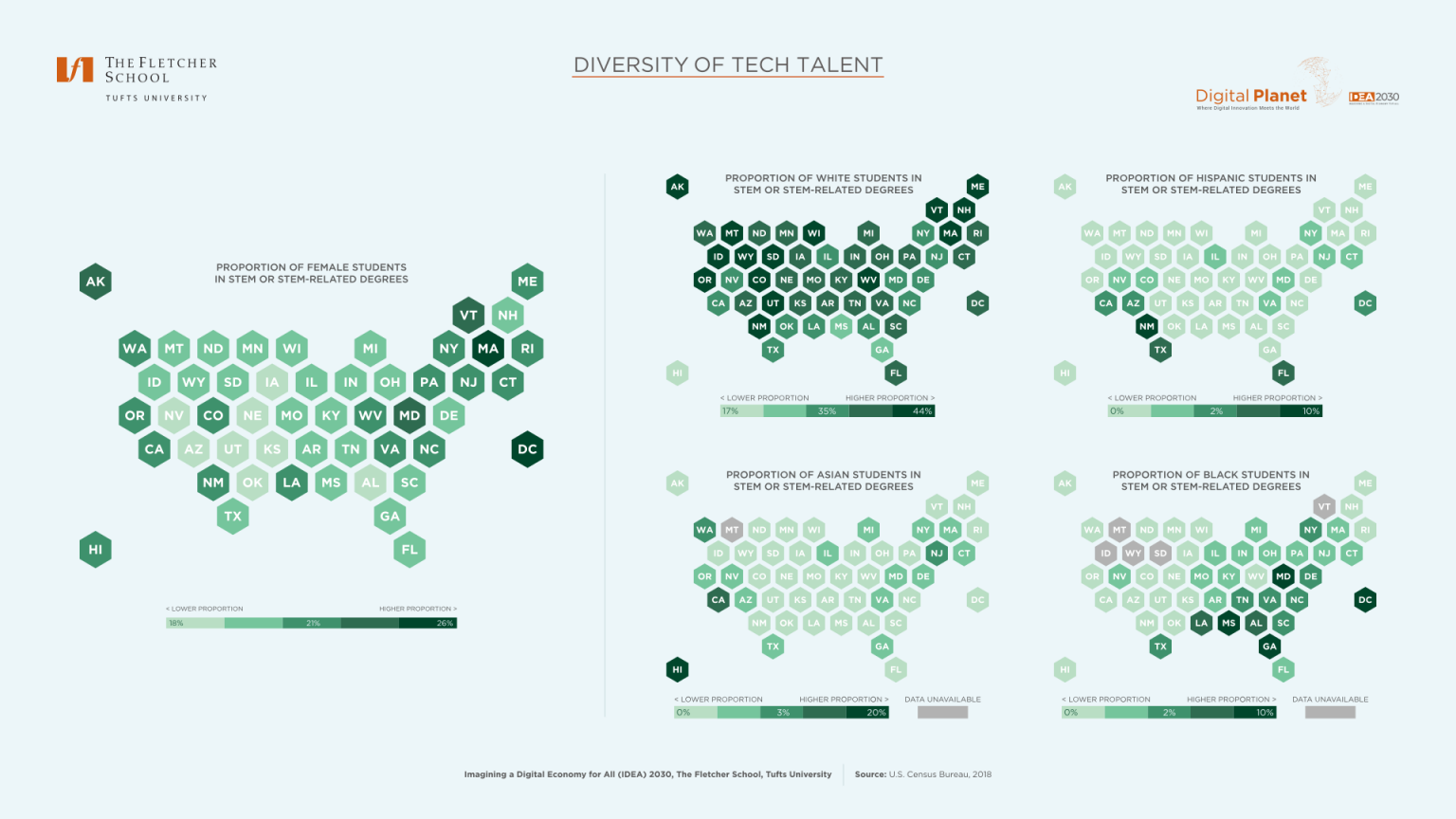

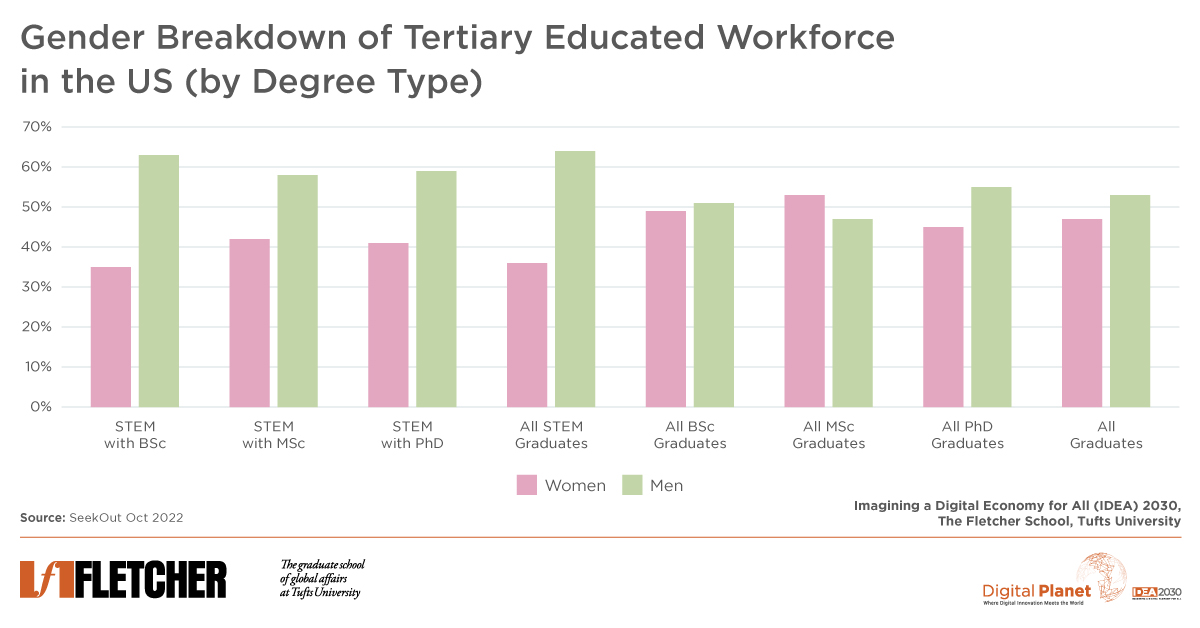

In this analysis, we looked at the diversity of tech talent (i.e., the proportion of students pursuing STEM or STEM-related degrees, broken down by race, ethnicity, and gender) across the United States. Using this data, we computed a Tech Talent Diversity Score, which ranked states by their likelihood to house higher proportions of minority (Black, Hispanic, or female) students pursuing STEM or STEM-related degrees (i.e., a degree that is considered a prerequisite to land a tech job).

We first examine the tech industry’s size, cost of living, Tech Talent Diversity Score, and digital infrastructure capabilities and access on a state level, in order to understand opportunities that could broaden the tech industry’s geographic and demographic scope. After the state-level analysis, we did a similar analysis for a selected number of major cities to highlight the cities that could become the next inclusive tech hubs.

Demographic Breakdown of Tech Talent Diversity

The diversity of students pursuing STEM or STEM-related degrees is not consistent across the country, varying substantially depending on students’ race or ethnicity, and moderately based on their gender. California, New Mexico, Texas, and Florida have a higher representation of Hispanic students in STEM, while Maryland, Mississippi, Georgia, and the District of Columbia house the highest proportions of Black students pursuing STEM degrees (both in absolute and relative terms).

There are two disparate factors simultaneously at play that are exacerbating the diversity gap:

- Most of the tech industry’s growth is happening disproportionately in states like Washington (primarily in Seattle), Massachusetts (primarily in Boston), and California (primarily in San Francisco), where the presence of minority STEM students is relatively scarce.

- Black and Hispanic workers are vastly overrepresented in low-tech occupations and underrepresented in digital, high-tech, higher-pay occupations.

Pandemic-induced work-from-home policies—now slated to be in place for most of 2021 (if not indefinitely)—could serve as a catalyst for the tech industry to narrow these regional and demographic disparities. Tech companies now have the opportunity to be deliberate in their regional de-concentration, given that remote work is proving to be an acceptable norm. Such a shift could allow more cities and demographics to contribute to and prosper from the tech industry’s economic growth.

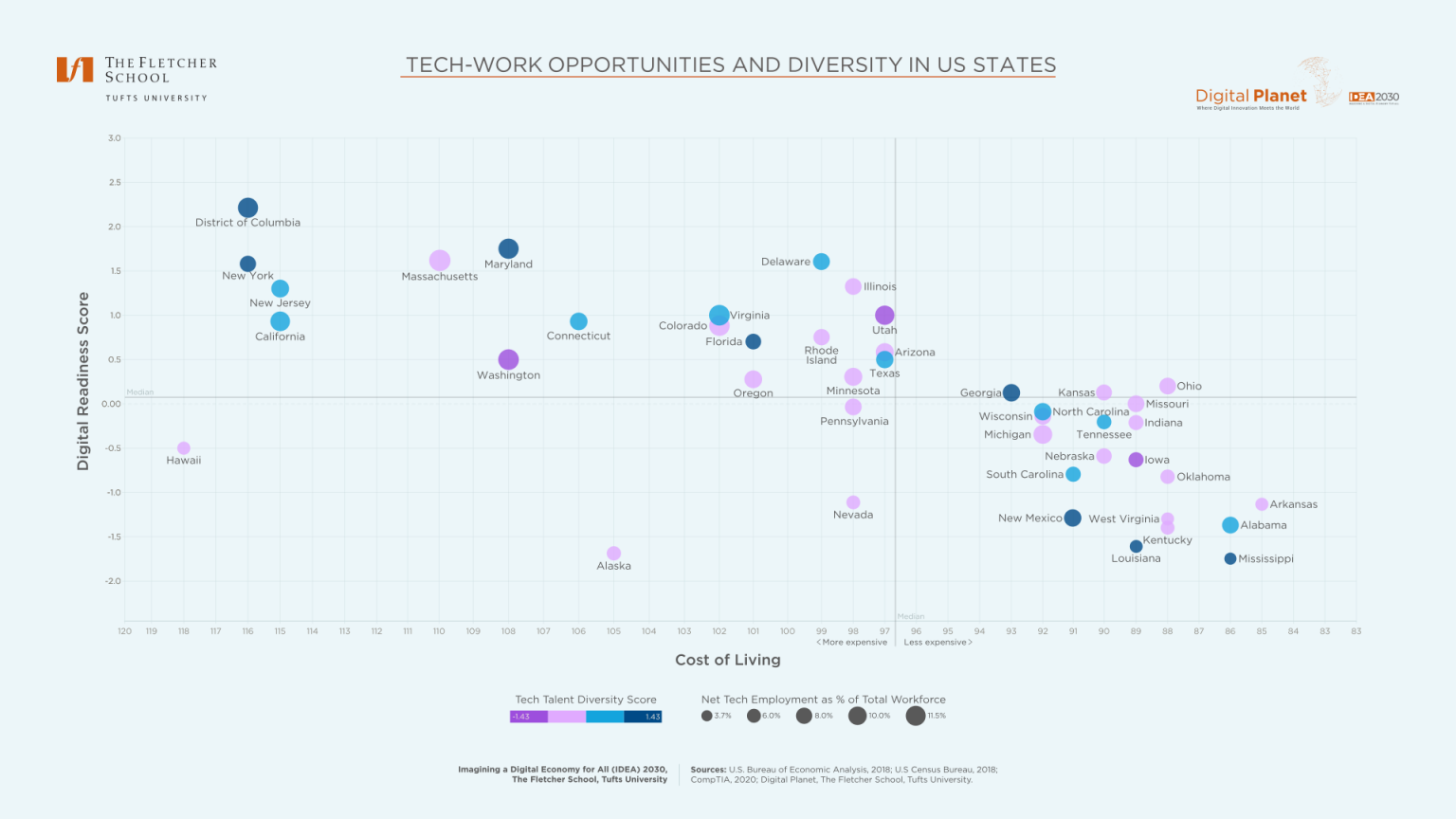

Superior Digital Infrastructure in Tech Hubs Justifies their Higher Costs of Living

While the goal of fostering tech hubs and startup ecosystems beyond the current handful of states is crucial, the feasibility of a tech hub expansion to states outside Washington, California, New York, and Massachusetts remains difficult. Many states simply do not have the necessary digital infrastructure to support a thriving tech industry. A comparison of states’ digital readiness with their costs of living reveals an interesting pattern (R2: 0.45; p-value: <.0001): states (except for Hawaii, Alaska, and Nevada) that ranked above average on their digital readiness scores also fell on the higher side of the US Economic Bureau’s cost of living (purchasing power parity) score. Similarly, affordable states with lower costs of living consistently fell below the mark on their digital readiness.

However, compared to Washington or Massachusetts—prominent tech hub states in the country—states like Georgia, Texas, Virginia, Connecticut, Maryland, and Delaware are more digitally ready, more diverse, and the lower cost of living makes it more cost effective for employees and employers, making them a core set of “target states,” representing an untapped opportunity for technology companies to establish offices and recruit the abundantly diverse pool of in-state talent.

In the medium term, with remote-work becoming normalized and a stated preference for many workers, the time may be ripe for a regional deconcentration of the tech industry—ideally across the heartland—through explicit policy interventions. A tech-era renovation of the growth pole strategy of the 1960s—focused on investing in the digital infrastructure of overlooked regions—could spur economic activity and raise wellbeing across a number of cities outside of the major tech hubs.

In the immediate term, if tech companies choose to be intentional, and not just aspirational, about diversity in their hiring practices, then the new remote work trends imposed by the pandemic present an opportunity for them to seek out geographically dispersed and minority STEM students and hire, train, and onboard them remotely. Pandemic-induced remote hiring processes have the potential to build economic and social welfare in at least two ways:

- By enabling tech talent to partake in the industry while staying closer to their home communities, the tech centers can potentially be more dispersed—increasing the share of metro areas that can benefit from the tech industry’s economic growth potential;

- By using the flexibility of remote hiring to reach out to minority talent, the industry can move towards being less demographically clustered, allowing minority talent to make inroads into the insofar exclusive tech networks (kickstarting the process of building representative tech networks in the country).

Looking Beyond States to Find Promising, Digitally Superior, and Affordable Cities

Another trend brought in by pandemic-induced remote working has been the relocation of current tech employees to less dense and more affordable cities. While cities outside of the major tech hubs continued to miss out on the dynamism brought in by the tech industry networks, the likes of San Francisco and Boston became increasingly unaffordable and crowded: a trend which could now be shifting.

While these relocations might only be temporary, this phenomenon could begin to foster a network of tech workers in cities outside the top 5 or 10 of the current tech hotspot cities. Startup events, networking opportunities, aspiring students and tech workers, as well as the presence of investors and entrepreneurs, are important contributors to a city’s ability to capture the interest of and nurture a tech ecosystem.

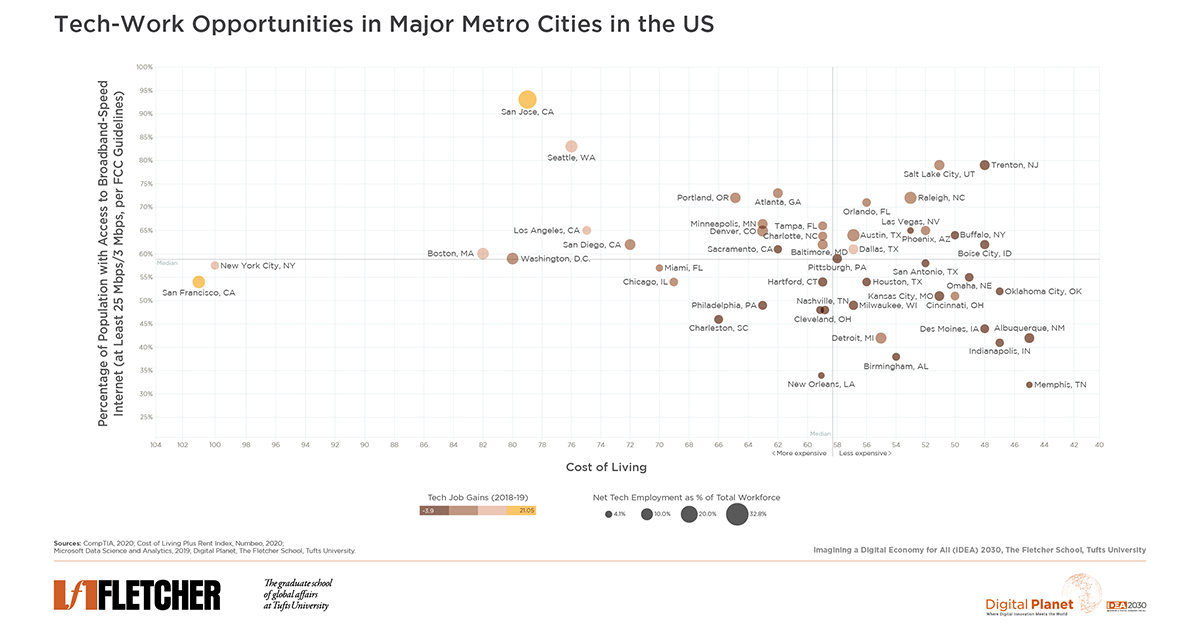

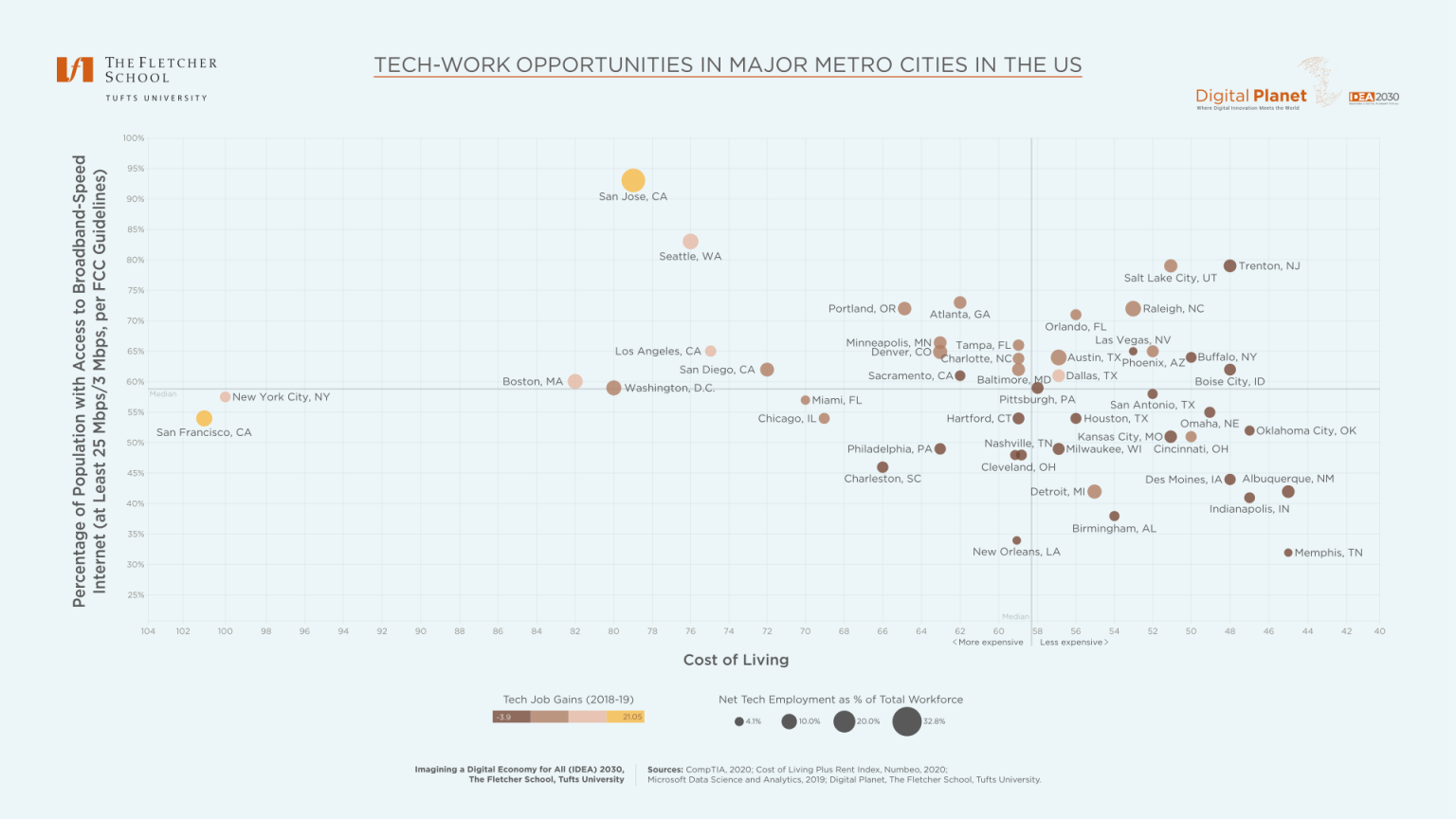

The chart below looks at broadband access (at FCC-recommended levels) in major US cities, compared to their cost of living. Many cities across the country are thriving in contrast to their states’ overall trends in terms of digital infrastructure and the presence of minority tech talent (as seen in the earlier chart above).

Cities like Salt Lake City, Trenton, Raleigh, Orlando, Buffalo, Boise City, Charlotte, Dallas, Austin, Atlanta, and Phoenix are all well positioned to support the digital needs of tech workers while allowing them to live in affordable spaces. These cities rank higher than tech hubs like San Francisco, New York City, San Diego, Los Angeles, and Boston when it comes to greater access to FCC-approved levels of broadband access among their populations. Furthermore, from a cost of living perspective, they are almost 30% to 40% less expensive than cities like Boston, and almost 50% cheaper than cities like San Francisco and New York City.

Pandemic-induced work from home policies have enabled tech workers based in expensive cities like San Francisco to look for succor in affordable, less dense cities with good quality digital infrastructure. Moving from San Francisco or San Diego to Sacramento, or moving from New York City to Trenton, or even from Tampa to Orlando provides an opportunity for tech workers to reside in spacious, inexpensive, and equally (if not better) digitally connected cities. It’s time for tech employers to follow the migratory instincts of their employees, and seek out more geographically diverse talent pools. Technology companies desirous of improving the diversity of their workforce would do well to let go of the geographic constraints tying them to a handful of “superstar” cities and decluster their recruitment strategy to reach a more diverse talent pool dispersed across the nation. Research shows that “for every job created in the high-tech sector, another 4.3 jobs emerge over time in the local economy;” de-clustering of the tech-sector could help generate inclusive growth dividends across the country.

Research Methodology

Index compilation methodology for scores follows the guidelines laid out by the OECD in their gold-standard Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators. Weights for the indicators, clusters, and component hierarchy were assigned according to expert input under a budget allocation process (BAP).

Digital Readiness Score

While only part of any economy’s work can be done remotely, Digital Planet examined the 50 states’ “digital reflex” by compiling a Digital Readiness Score for each state plus the District of Columbia. The Digital Readiness Scores are constructed using two indices:

- Work from Home Readiness; and

- Inclusive Internet and Digital Public Services

Work from Home Readiness

In a post-pandemic world, remote working could become the new norm for many people. Realizing that not everyone can work from home, the Work from Home Readiness Index was developed using a range of indicators to assess the extent to which each state’s selected labor force could work from home. Some key measures include the state’s proportion of essential workers, access to technology devices at home, estimated share of the labor force that can work remotely, percent of the population that holds a bachelor’s degree or higher, unemployment claims since March 1, 2020, and the size of the information and services industry. Please refer to the datasheet for a full breakdown of indicator inputs, sources, and weights.

Inclusive Internet and Digital Public Services

While the capacity to work from home is more important than ever, citizens must also be able to access these services reliably, with affordable, and inclusive internet. Broadband coverage, quality, and equity are important prerequisites for remote work. We captured inclusive and affordable internet using BroadbandNow’s research studies and census data from the American Community Survey. Additionally, our inclusive digital public services measure examines how states utilize technology to serve their communities during COVID-19, and factors in qualitative indicators such as the quality of COVID-19 data reporting between March and May, technology development as a priority to state officials, and municipal broadband roadblocks and restrictions. Please refer to the datasheet for a full breakdown of indicator inputs, sources, and weights.

With an unprecedented global pandemic prompting a marked reliance on digital services while workplaces, schools, and government offices remain closed, states which score higher on this axis are presumed to be better equipped to move to online channels during the crisis.

Tech Talent Diversity Score

The Tech Talent Diversity Score looked at the proportion of Black, Hispanic, and female students pursuing STEM or STEM-related degrees as a proportion of the total population of Black, Hispanic, or female students in each state, including the District of Columbia.

Using US Census Bureau data from 2018, we compiled each state’s normalized STEM degree representation across Black, Hispanic, and female students combined the three values—weighted equally. The score is an estimate of how many minority students are pursuing STEM or STEM-related degrees across each state so that if a tech company were to try and maximize its chances of hiring a minority tech worker, which are the states that can provide a diverse pipeline of tech talent.

Population with Access to Broadband

The proportion of people in a corresponding county that use the internet at broadband speeds, as of November 2019, was obtained from Microsoft Data Science and Analytics. Broadband speed as defined by the FCC is at least 25 Mbps/3 Mbps.

A note on missing data: North Dakota, New Hampshire, Maine, Wyoming, Idaho, Vermont, Montana, and South Dakota are missing from the chart titled ‘Tech-Work Opportunities and Diversity in US States’ due to lack of available data on their cost of living index (obtained from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2018).

All data and sources are available here.

Digital Planet Graduate Analysts Patrick Béliard, Malavika Krishnan and Devyani Singh worked on this analysis under the guidance of Bhaskar Chakravorti, Ravi Shankar Chaturvedi, Christina Filipovic, and Joy Zhang at Digital Planet, The Fletcher School, Tufts University.

This research is a part of the IDEA 2030 initiative, made possible by the generous support from the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth.