Global Digital Inclusion: Progress to Parity Scorecard

Benchmarking 90 economies’ progress in closing the gender, rural-urban, and socioeconomic digital divide.

The Progress to Parity scorecard was updated in September 2022. The latest edition can be found here.

Summary

We present the Progress to Digital Parity Scorecard—an interactive scorecard that tracks the journey towards realizing the goal of a digital economy for everyone, everywhere. This new framework draws on and builds upon the methodology and approach outlined in our Digital Intelligence Index. Our Progress to Digital Parity research compares each of the 90 economies in our study to a truly inclusive digital economy for all—regardless of one’s gender, socioeconomic status, or geographic location. It will be our endeavor to update and refresh this scorecard periodically, as and when the underlying data sources are updated.

Introduction

According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), over 40% of the world’s population was not using the internet as of 2020. Building upon this reality, several studies have taken one step further in understanding the digital divide through additional lenses—such as gender, geographic location, and socioeconomic status—and unanimously agree that inequities in digital access worsen when comparing the typically excluded groups to their typically included and relatively privileged peers.

To enable policymakers and decision-makers to tackle the extant inequities in digital access, we built this scorecard measuring progress towards achieving digital parity between the typically excluded and typically included using three lenses: gender, rural-urban, and socioeconomic status for 90 economies. Using data comparing digital access and literacy across these groups from the World Bank’s Global Findex and GSMA Intelligence, we calculated digital access and literacy in each of the typically excluded groups relative to the typically included. As a result, an economy where only 20% of women are digitally engaged has full progress to gender digital parity if only 20% of men are digitally engaged. Conversely, 70% of women digitally engaged may be less inclusive if 90% or more men are digitally engaged.

To put context behind the state of digital inclusion in an economy, we then imagined a hypothetical fully inclusive digital economy—with perfect parity in digital access and usage between the rich and the poor, men and women, and the rural and urban populations—and used it as a benchmark against which we normalized individual countries’ relative digital parity. This gives policymakers and decision-makers a measure of the extent of digital parity or lack thereof across individual dimensions and a handy sense of the distance to the frontier.

It is important to note that, given our methodology, some countries score above 100% on a given measure. Scoring above 100% means that the typically excluded group has greater digital access and usage than the typically included group in that economy. This is apparent in a select few economies across the gender and rural digital parity measures, and only one economy in the socioeconomic measure: New Zealand.

Digital Inclusion: Progress to Parity

An interactive tool benchmarking 90 economies’ progress in closing the digital divide among three measures: gender, rural-urban, and socioeconomic.

Parity Reference Line

% Progress to Digital Parity

How to read the charts

Our Progress to Parity interactive and scatterplots below are colored by the percentage of each country’s population using the internet (Euromonitor, 2021). A country colored in dark red has the lowest percent of its population using the internet, whereas a country colored in dark green has the highest percent of its population using the internet.

Red-colored countries that approach 100% progress to digital parity have a low percentage of their population using the internet, but the population using the internet does so equitably in the cluster of interest. These countries would do well to expand access to digital technologies in an equitable manner among the excluded populations.

On the other hand, green-colored countries with lower progress to digital parity demonstrate a broad use of the internet by the populace, albeit at inequitable rates in a given measure. These countries risk further marginalization of the typically excluded group and concentration of the benefits from a connected society among the included majority.

Each of our three scatterplots are organized with the respective progress to digital parity measure (on the Y-axis) against an analog measure (on the X-axis) to compare the dynamics of digital inequity in our set of countries. For gender digital parity, we used men and women in the workforce; for rural-urban digital parity, we used the level of urbanization; and for socioeconomic digital parity, we used wealth inequality as our analog measures. The relationship between each respective analog and digital parity variable are positive; a lower value for the analog measure tends to pair with lower progress to digital parity, and vice-versa.

What is the relationship between digital and analog inclusivity across and within countries?

Explore the scatterplots below.

Gender Digital Inclusion: Progress to Parity

Performance in our progress to gender digital parity scatterplot is widely cultural. Countries in the Middle East & North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America & Caribbean, and South Asia underperform the global median, on net, while countries in Europe & Central Asia, North America, and East Asia & Pacific tend to outperform the global median.

Median Reference Line

Observations

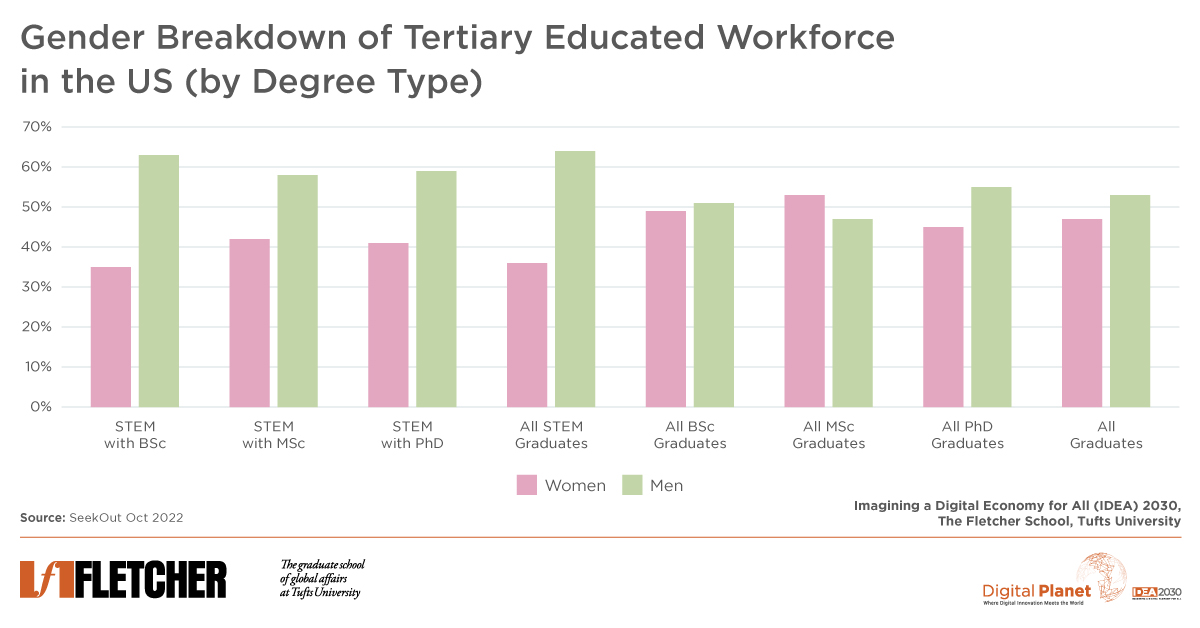

Our first scatterplot combines our progress to gender digital parity metric with a measure of workforce parity between men and women. Our X-axis takes the most recently available labor force participation rate data from each of the included economies, as measured by UNESCO. This tells us: for every man in the labor force in a country, what fraction of women are in the labor force?

The vast majority of economies fall into the bottom left and top right quadrants, as is to be expected; higher workforce parity between men and women tends to correlate with higher digital parity between men and women. Countries in the bottom left tend to be clustered in the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, and South America. Our exemplary sample of countries in the top right is made up primarily from countries in Europe and Central Asia, North America, and a select few East Asia & Pacific countries. The only sub-Saharan African country is Namibia, while the only Middle East & African country is Israel; each country cites equality for women as a right in their respective constitution and declarations of independence.

Country Spotlight: The Philippines

The Philippines, in the top left quadrant, serves as an interesting case study. The Philippines has been driving the changes in closing the gender gap on many fronts. According to the 2021 World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Gender Report, the Philippines is one of the few countries that has closed its gender gap in senior roles, and in professional and technical roles. Moreover, it was ranked in the top 20 on the WEF’s Global Gender Gap Index, right behind France, Costa Rica, and Spain. Regarding the use of digital money and financial services, the latest World Bank Findex data also suggests that in the Philippines, women use digital payments at a 14% higher rate than men, and women might have better savings behavior than men. Culturally, women are often in charge of the household finances, meaning it may be more likely for a woman to open a bank account in her name. In addition, owing to the country’s efforts to promote ICT training for women and its long history of skill training in the health sector, it should come as no surprise that the Philippines has over 100% progress to gender digital parity.

Despite high levels of financial inclusion of women in the country, the Philippines still lags its peers in gender equity in labor force participation. For every 100 men, only about 64 women participate in the workforce. The National Economic and Development Authority’s publication “Determinants of Female Labor Force Participation in the Philippines” finds that reasons for this low labor force participation rate are similar to the same stereotyped gender roles that relegate Filipino women to domestic roles, like managing household duties and related finances.

Implications for Action

Countries in the bottom left could improve their gender digital parity by first creating a level playing field in society for women across education, employment, social, and cultural fronts. These countries should start with equity for women in written law—where, according to the most recent Women, Business & Law report, many of these countries do not have women equal in written law— as a baseline to promoting all-encompassing parity. Second, countries with relatively even digital parity but uneven labor participation among men and women could focus on targeted trainings and education to increase female labor participation.

Lastly, countries that have high equality in labor force participation yet have low progress to gender digital parity should focus on ensuring equitable digital access and technology among women and men. Government-led programs such as low-cost courses on digital transformation competency development and free Wi-Fi for all that provides reliable internet access in public spaces (i.e. public schools, universities, parks and hospitals) could help bridge such gaps. In addition, given that our progress to gender digital parity measure includes many digital finance indicators (ratio of women to men using a bank account, for instance), this difference may reflect that men are disproportionately in control of the household’s finances.

Rural Digital Inclusion: Progress to Parity

Globally, people living in urban areas are nearly twice as likely to use internet than those in rural areas, with the gap widening in the developing world. Understanding the unique context of each country is key to closing the rural-urban digital divide.

Median Reference Line

Observations

To contextualize countries’ progress towards rural digital parity, we compared it against each country’s percent of population living in urban areas as of 2020. We anticipated that countries with a higher percentage of their populations living in urban areas were more likely to have above-median progress to rural digital parity, since there are relatively fewer rural people to reach with digital technologies in those countries. Additionally, urbanized economies tend to yield higher per-capita income, giving governments greater ability to build out digital infrastructure to reach its rural population. These economies lie in the top right quadrant of our scatterplot.

Our most intriguing success stories of progress to rural digital parity exist, therefore, in the top left quadrant. These economies have a large percentage of their populations in rural areas, yet the people in these rural areas access digital technologies at nearly the same rates as the average for the entire country.

Country Spotlight: Kenya and Uganda

The widespread use of mobile money may provide some explanation for why some countries find themselves in the top left quadrant. Kenya and Uganda offer up good case studies for other emerging markets hoping to close the urban-rural digital divide. In the past decade, mobile money services using no or low-internet bandwidth have proved to generate financial resilience and facilitate higher savings for less affluent rural households in the global south. Since Kenya launched M-Pesa in 2007, the text-message based money transferring service has reached more than 30 million customers across the globe. Kenya’s neighboring country, Uganda, has also succeeded after introducing the mobile money service in 2009. Besides being two of the early adopters, the Kenyan and Ugandan governments’ willingness to work with influential players in the sector (large mobile operators such as Vodafone’s Safaricom and MTN) coupled with “light touch” regulation propelled the use of mobile money among their citizens, across both urban and rural locations.

Implications for Action

Of the 600 million people worldwide living outside of mobile network coverage, 67% are in sub-Saharan Africa, and the percentage of unconnected is disproportionally higher in rural and far-reaching areas. Countries with a large rural population yet low digital parity could do well by investing in increasing digital infrastructure and hardware access for all the population. While digital transformation takes time, countries should explore low bandwidth options to help rural citizens come online. Programs such as M-Pesa and other text message-based financial services are adoption-worthy examples for countries intent on closing the rural-urban digital divide.

Meanwhile, highly urbanized economies that have relatively high shares of information and services industries should pay particular attention to the unevenness in digital access and literacy among their rural populations, making sure they are not falling further behind in access and literacy.

Socioeconomic Digital Inclusion: Progress to Parity

European economies (especially Scandinavian economies) are stalwarts for including the poorest in their economies; they provide a benchmark for economies striving for equal digital access between the rich and poor, through a robust marginal tax system combined with inclusive education that fosters equitable digital literacy.

Median Reference Line

Observations

Finally, to investigate the dynamics of our scores for progress to socioeconomic digital parity, we analyzed the latest Gini Coefficient estimates for our DII countries from the World Bank, a measure of the relative distribution of that country’s wealth. Countries with a higher percentage of income in the hands of a smaller percentage of the population have higher inequality, and thus a higher Gini coefficient. To yield consistency between our scatterplots, we inverted the Gini coefficient on the X-axis such that values on left side of the chart represent higher inequality, and values on the right side of the chart represent lower inequality.

The stalwarts of combined wealth equality and substantial progress to socioeconomic digital parity are primarily in Europe, especially in Scandinavia. One of the primary reasons for low readings of wealth inequality in this region is high marginal tax rates for wealthy individuals, approaching 70% for some countries. In turn, Scandinavian countries have much higher government revenues as a percent of GDP compared to the rest of the world: Denmark ranked first in the world with tax revenues totaling 34% of its nominal GDP in 2019. Scandinavian countries take those elevated tax revenues and invest in education for all (with Denmark, Norway and Sweden three of the top four high income countries in average government expenditure on education as a percent of GDP since 2008). As Jackman et. al find, a more robust education leads to higher digital literacy, rounding out Scandinavia’s elite ranking in our progress to socioeconomic digital parity scores.

Meanwhile, the bottom left quadrant has high income inequality and low progress to digital parity. Countries in this region are primarily clustered in South America, where relatively low average tax rates have propelled growth in the richest portions of the economies, and sub-Saharan Africa, where economic growth has been driven by sectors with low levels of lower-skilled labor.

Country Spotlight: The United States

Perhaps the most interesting story in our research of socioeconomic digital parity are the countries in the top left corner of the scatterplot, with high-income inequality yet above-median progress to socioeconomic digital parity. Of the countries in this quadrant, the only high-income country (as defined by the World Bank) is the United States. Despite its world-leading real Gross Domestic Product of approximately $19.7 trillion, 11.4% of the United States population were below the poverty line as of 2020. The United States’ 71.31% progress to socioeconomic digital parity underperforms its high-income peers’ median value of 85.67%.

This large low-income population, coupled with the United States’ abnormally high internet costs, is a large driver in the nearly 30 percentage-point gap between it and the perfect socioeconomic digital parity line. Alongside affordability, access to reliable internet is an issue; since the US has the second-largest surface area among high-income countries, providing all Americans with internet is a large challenge. Because rural America tends to have lower per capita income than urban America, this exacerbates the United States’ relatively low progress to socioeconomic digital parity.

Implications for Action

As demonstrated by Scandinavia, investment in accessible education for all is a gateway to creating a digitally literate society. These economies tend to leverage higher tax revenues from high marginal tax rates on the wealthy to even the playing field in digital access and literacy between the poor and rich in their societies.

As further explored in other ongoing research by Digital Planet, there is an inverse relationship between the growth rate of innovation and progress to socioeconomic digital parity in the top 1/3 of digitally advanced economies in our 90 Digital Intelligence Index economies. As such, policymakers for digitally advanced economies must find the right balance between policies focused on attracting risk capital into the technology sector—which tends to concentrate wealth among the relative few—and attracting and making investments into public goods, such as education and digital skills, to foster a more inclusive digital economy.

As the world begins to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, the digital divide is more likely than ever to widen inequality in income and socioeconomic wellbeing in and between countries, particularly in countries with lower progress to socioeconomic digital parity. Governments must actively invest in raising digital literacy and skills of all in order to counteract this trend. Evaluating New Zealand’s Digital Inclusion Blueprint, which prioritizes digital literacy among current non-users of technology, as a benchmark for action is a good place to start.

Research Methodology

The Progress to Digital Parity research builds upon methodology followed in the last iteration of the Digital Intelligence Index (DII). The 90 economies included in this comparison across the three areas of digital inclusion—gender, rural, and socioeconomic—are consistent with the economies evaluated in the DII.

The 16 indicators used in Progress to Digital Parity come from two sources—the World Bank’s Global Findex and GSMA Intelligence. Each indicator compares the typically excluded group (the poorest 40% for the socioeconomic cluster, women for the gender cluster, and the population living in rural areas for the rural cluster) to the privileged, generally more included group (the richest 60%, men, and the average of the country’s geography) in its respective cluster. The weight of each indicator within the three clusters is determined based on data quality, strength of collection methods, and centrality to the respective cluster. Any of the 90 economies that had missing data points for those 16 indicators were estimated using the methodology of the DII:

- Where any observations exist for a given economy and indicator, our estimation method first relies on Stineman interpolation to fill in missingness between observed datapoints. Next, NOCB (next observation carried backward) and LOCF (last observation carried forward) treatments are applied to fill in missingness outside observed data range.

- Where no observations exist for a given economy and indicator, our estimation method relies on recursive rounds of targeted mean imputation to fill in missing values, whereby missing values are estimated as the average of the sample observations of the most characteristically similar economies for the same year as the missing datapoint. Estimated data points are then given similar interpolation, NOCB, and LOCF treatments.

The parity line that countries are compared against has values for its indicators manually coded such that the poorest 40% has equal digital access to the richest 60%, women have equal digital access to men, and the rural population has equal digital access to the average population.

The fully estimated data for the 90 economies are grouped together with data for the parity line. Normalized values are then created for countries in each of the three clusters. For the final measure of percent of progress to digital parity, the country scores are compared to the parity line in that cluster. Readings below 100% progress to parity mean that the typically excluded group has lower digital access than the privileged group in that economy. Readings equal to 100% mean that the typically excluded group has equal digital access to the privileged group. Finally, readings above 100% mean that the typically excluded group has greater digital access than the privileged group in that economy. This is apparent in a select few economies across the Gender and Rural digital parity clusters, and only one economy in the Socioeconomic cluster: New Zealand.

Research methodology: Scatterplots

In order to contextualize the dynamics of parity between the typically excluded and typically privileged in our three measures, we plotted progress to digital parity against three analog variables. Two of these variables—the Gini coefficient for socioeconomic digital parity and percent of population living in urban areas – were stock data collected from the World Bank. However, we calculated the analog measure used for the gender digital parity scatterplot – female labor force participation parity. The labor force participation rate in a country measures the percentage of the working-age population (aged 15 or older) that is either working or actively searching for work. UNESCO disaggregates this data by gender. Using this disaggregated data, Digital Planet divided each country’s most recent female labor force participation rate by that country’s male labor force participation rate.

Quality Assurance

Throughout the imputation, weighting, standardizing, and aggregation processes, we adopted several quality assurance measures to ensure the validity and robustness of the Progress to Parity values. By deploying different statistical tools throughout the process, including data cleaning, variance analysis, regression analysis, and simulations, we stress-tested the values at multiple levels to produce the most comprehensive and robust numbers possible. Any economy’s scores that jumped out as outliers in the index in the QA process were rigorously checked to make sure that the data in that economy are accurate and robust. This mitigates the chances of systematic errors in the process.

Click here to download the interactive Progress to Digital Parity dataset.

This research is a part of the IDEA 2030 initiative, made possible by the generous support from the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth.