Home > Off the Charts > Delivering Public Services During COVID-19

Delivering Public Services During COVID-19

A Country-by-Country Analysis

The delivery of public services online requires two necessary conditions: the infrastructure — hardware and software — for governments to deliver public services digitally, and abundant availability of affordable internet access. We scored and arrayed 42 countries on these two aspects: (1) digital public services and (2) inclusive and affordable internet. Additionally, we wove in a snapshot of the stringency of government lockdown and social distancing mandates into this analysis. We picked April 8, 2020 — a moment in time shortly after global confirmed COVID-19 cases hit 1 million, and two days after British Prime Minister Boris Johnson went into intensive care — as a snapshot for this stringency measure because it was in many ways a key turning point for many countries. Since several countries in Europe began to ease lockdowns around mid-April, this date provides a view of many countries at their most “stringent” point in time.

Key Observations and Insights

A look at the scatter plots above shows a strong positive correlation between digital public services capabilities and inclusive and affordable internet. We examine a selection of countries across the diagonal from worst to best below.

While the Philippines has endeavored to provide government services via an online, one-stop portal by 2023, reports show that the country is behind schedule in implementing the necessary digital infrastructure. Combined with a distinct lack of inclusive and affordable internet access, the country’s citizens are unlikely to be able to access key public services during a period of lockdown. While limited online public services, such as requesting birth and death certificates, do exist under normal circumstances, these offices were closed during the Enhanced Community Quarantine for 48 days, leaving citizens without access to important documents they might need to get the ball rolling for other benefits. With the country’s decentralized system, bureaucratic red-tape, and nascent technology, effective public service delivery poses a challenge, particularly for the poor and marginalized.

India falls close to the middle in both digital public services and inclusive and affordable internet. The government’s 2009 rollout of Aadhaar, a digital biometric ID, has been crucial in ensuring that 1.2 billion citizens retain access to benefits during lockdown. The JAM trinity, incorporating low-cost bank accounts with Aadhaar and mobile numbers, has facilitated the delivery of public services such as food, subsidies, and direct benefit transfers straight into the hands of those who need it. A centralized National Government Services Portal allows for online tax filing and obtaining a driver’s license, while the mobile app UMANG provides a single platform to access India’s e-Gov services. However, India still has significant room to grow with just 40% of the population holding an internet subscription. Reducing the digital divide therefore, combined with user interface upgrades, will move India in the right direction.

New Zealand has effectively eradicated coronavirus by enacting stringent measures, while relying on an integrated digital government to consistently deliver public services. Residents have a centralized website to go to for ordering death certificates, applying for food programs, accessing health services, and receiving tax credits using their secure digital identity. During the lockdown, people could file online applications for crisis benefits and access official information through WhatsApp. Services are increasingly designed around a life’s journey, like SmartStart for new parents and the world’s first end-to-end online passport service. Though the country has built firm digital foundations, it should also remain focused on addressing digital exclusion concerns from those on the margins.

The Swedish government is primed to deliver key public services online, yet out of all countries in the plot, Sweden adopted the least stringent response. From obtaining birth and death certificates online and receiving secure digital mail, to making medical appointments, filing taxes, and claiming unemployment benefits, Sweden’s e-government and society are inextricably digitized. Sweden’s digital efforts to drive public sector efficiency has been largely successful with 8 million BankID users and 95% of the population using the internet.

Nevertheless, the country controversially refrained from instituting a full lockdown, instead allowing daily life to continue. Indeed, given that Sweden has strong digital capabilities that it could rely on, combined with high levels of trust in the government, it is well positioned to enforce stricter regulations while keeping its citizenry engaged.

Singapore boasts the highest digital public services and society score, though it maintained a less stringent response (as of April 8) due to its early success in containing the disease. The city-state has been leading the charge for digital public services, with an aim for almost all government services to be accessed online by 2023. Using a central SingPass, people can access their social security benefits, taxes, retirement schemes, and health insurance — a small selection out of more than 1,600 online and 300 mobile services. New parents can register births, access immunization and health records, navigate childcare options, and apply for tax benefits all in one place. Residents could even pay for street parking and order prescription refills online. Over 93% of individuals and almost 100% of businesses used digital government services in 2019.

Given Singapore’s existing digital infrastructure and engineering capabilities, the country is extremely well-equipped for social distancing, while continuously engaging citizens through public awareness campaigns. By May 14, Singapore adopted a much more stringent government response, instituting a lockdown (except for essential services), closing schools and restaurants, and punishing those who disobey orders to arrest a second wave of infections that accounted for over 92% of all cases in the country to date. Key digital tools to manage the crisis include contact tracing apps, travel and health declaration systems, automatic temperature screening gantries, and strict quarantine monitoring protocols.

In conclusion, this analysis gives policymakers a sense of where they stand in terms of social distancing preparedness, particularly in the face of decisions to re-open economies and resume normal activities. Should they need to return to a period of stricter policies to combat second waves, they now know their full capacity and can act accordingly. The pandemic has accelerated the uptake of digital services, and it is crucial that investments in digital infrastructure like government-to-people (G2P) payment systems continue, in order to promote an engaged, united, and resilient citizenry.

Research Methodology

Index compilation methodology for scores follows the guidelines laid out by the OECD in their gold-standard Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators. Weights for the indicators, clusters, and component hierarchy were assigned according to expert input under a budget allocation process (BAP).

Digital Public Services

Digital Public Service scores are compiled from six component sub-scores:

– Digital Facilitation of Public Services, which measures the accessibility of government services online

– Government-to-Citizen Digital Payments, which scores the use of digital payments in government-to-citizen transactions

– Digital Democracy, which assesses the existence of online channels for citizen-to-government feedback

– National Digital ID, which rewards the deployment of a universal electronic ID system

-Institutions and the Digital Ecosystem, which indicates the government’s standing commitment to forward-looking digital technology

– Safety Net Adequacy, which examines whether governments provide basic social safety net guarantees to their citizens under extreme duress

With an unprecedented economic downturn prompting greater and greater reliance on governments while government offices remain closed, nations who score higher on this axis are presumed to be better equipped to satisfy the basic needs of their citizenry during the crisis and to do so via online channels.

Inclusive and Affordable Internet

While the provision of digital public services is more important than ever, citizens must also be able to access these services—not to mention schooling, work, and entertainment— with affordable and inclusive internet service. Index scores for our second axis, Inclusive and Affordable Internet, thus quantifies the relative accessibility of internet service by country.

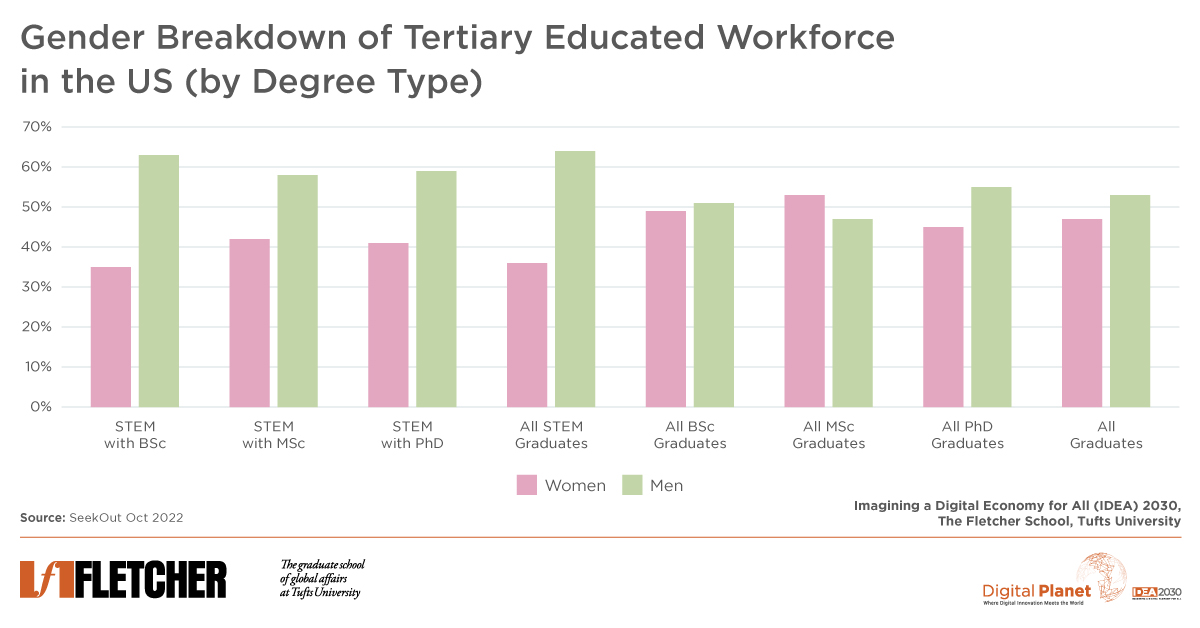

Scores for this second axis are broken down by its two major components: (1) Affordability and (2) Inclusion. Inclusion scores account for five dimensions of digital inclusion that assess both government efforts to facilitate greater inclusion as well as inclusion outcomes: Gender Digital Inclusion, Class Digital Inclusion, Government Inclusion Efforts, National Broadband Strategy, and Internet Access Fundamentals. Internet affordability scores are made up of price baskets for mobile and fixed broadband normalized for %GNI PPP per capita as well as metrics on broadband market concentration.

Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT)

The OxCGRT measures which governments around the globe have taken different measures, and when. Our graph uses a snapshot in time (the date is on the color scale) to examine the stringency of various government responses. For more information on Oxford’s COVID-19 Government Responses Tracker, please visit their site: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker

A full breakdown of inputs and weighting schemes for both axes can be found here.