In her article “The Story Behind the Green Air Force 1s Virgil Abloh Made Exclusively for Museum Guards”, Eileen Cartter explores the latest exhibition on display in the Brooklyn Museum: a retrospective show about Vergil Abloh’s long and historic career in fashion design, art, sculpture, and architecture. The show was originally co-curated by Abloh and Antwuan Sargent but following the designer’s passing in late 2021, it became a solo curation by Sargent. The exhibition has rooms of sneakers, sculptures, and archival books of Abloh’s design work for Louis Vuitton during his historic revitalization of their menswear collections. Notably in the middle gallery is a gift shop called “Church and State” that sells exclusive merchandise relating to the exhibition. However, the most exclusive Abloh design in the exhibition was the one no one could take home: the outfits and sneakers made specially for the guards.

Abloh was best known for his ambitious sneaker designs and for collaborating with other brands to make exclusive short runs of sneakers, which merged art and commerce (like “Church and State”). He was a firm believer that art could not exist without commerce, and vice versa. But he also was a believer in the power of democratizing art[1]. While a few hundred dollars is a steep price for sneakers to most consumers, they are a piece of wearable art and considerably cheaper than most artworks that can be purchased at auction or in an artist’s studio. They are collectible capitalism, which was a concept that fascinated the designer. In some way everyone could own art, even if it was mass produced. But what happens when people are allowed to wear art that no one else can but are not allowed to own it? As the Brooklyn Museum has discovered with their guard outfits and sneakers, a paradox of exclusivity, objectification, power, and money emerges.

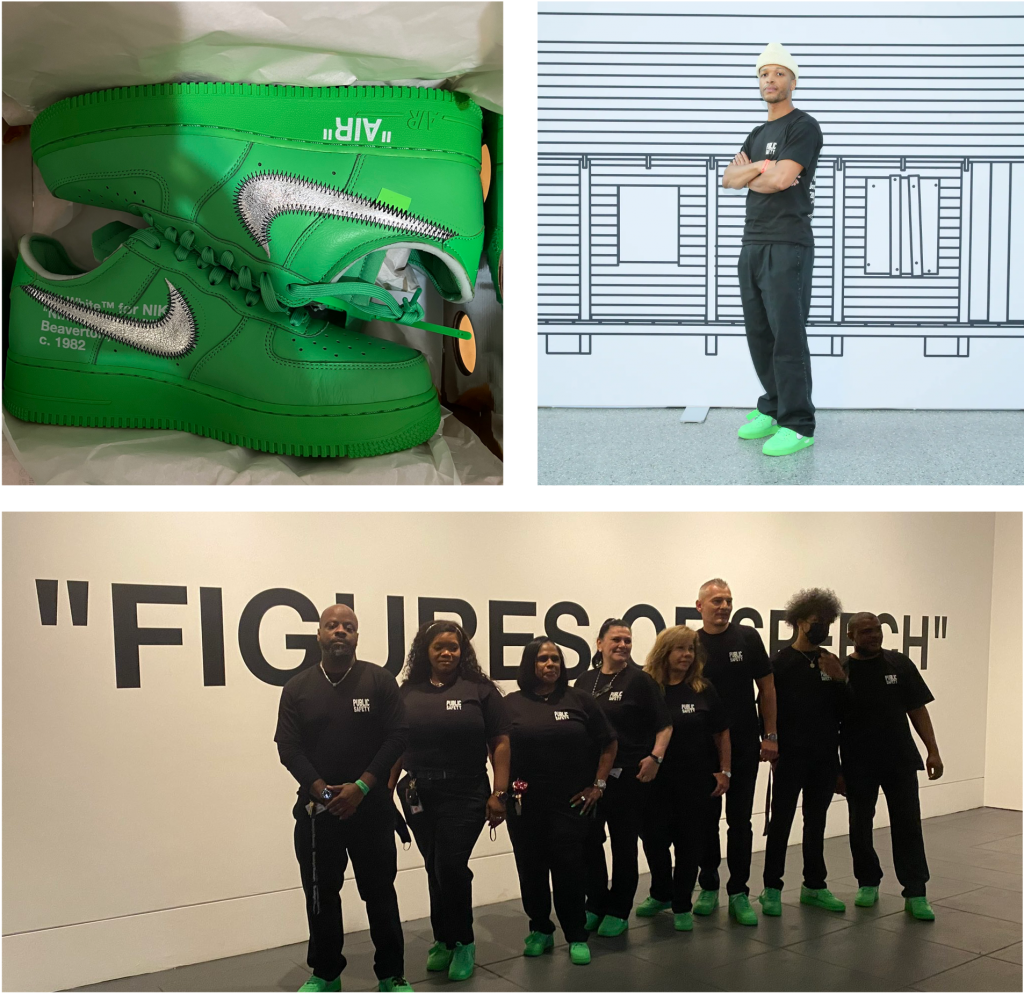

The look in question is a black tee shirt that reads “PUBLIC SAFETY” across the front, black joggers, and electric green low top Nike Air Force 1’s. The very choice of all black with bright green shoes highlights how special they are, and in an exhibition space where many visitors are interested collectors, appreciators, and owners of shoes, they stand out while the people the shoes are attached to stand watch for the safety and success of the exhibition. Guards are not allowed to take their outfits home and must keep them in special lockers at the museum.[2] They can only wear the look when working in the exhibition space and are not allowed to sell any pieces to anxious sneakerheads with hundreds or thousands of dollars in hand. The outfits are so exclusive that the museum had to stop accepting guard applications from obsessed fashion collectors hoping to nab a pair of the shoes to sell online for staggering profits.

Throughout his career, Abloh was very aware of the collectability of his pieces and the way that the resale market played into the perceived value of each sneaker design. This was considered when placing the merchandise store in the middle of the exhibition space, encouraging those who had bought tickets just to get to the gift shop to actually look at the art around them before buying large bags of items to resell. The items in the gift shop were also designed with collectability in mind. With such a focus on owning material culture in the exhibition, the inability of the guards to own the shoes they are required to wear on their feet seems like it goes against all that Abloh stood for in his design work. If one of the guiding principles in all his designs was to make fashion accessible and subvert the hierarchy of designer brands by embracing streetwear, then why deny the people safeguarding a collection of those democratizing designs the ability to own the shoes on their feet?

One argument for this practice could be that if the guards wear the shoes outside of the museum, they could be damaged, stolen, or sold. This would mean that the museum would have to come up with another pair of specially made shoes in the guard’s size or that they would simply lose a worker in the space. If the guards were to wear their shoes home, they could also be attacked and have the shoes stolen due to the popularity and notoriety of the exhibition. Since these shoes are exclusive, they are as valuable as the art on display, if not more so because they cannot be purchased in a Nike store or in an online auction. However, by having staff members of the museum that are often overlooked or ignored wear the art that is not on display, they effectively become models and mannequins for people to stare at.

This creation of mannequins out of guards is an interesting contrast to both the intentions of Abloh and also to the inspiration for the outfits: Fred Wilson’s work Guarded View (1991)[3], which consists of four black headless mannequins wearing the uniforms of prominent New York City museums. This work was very impactful and highlighted the anonymity of museum guards and how many are people of color from working class backgrounds. The uniform is all that patrons see, and so the person becomes invisible. In some ways, Abloh’s shoes also play with this idea of the uniform being the only thing that people see when visiting the space, but instead of becoming invisible the guards are almost hyper-visible because of the shoes they wear and the inherent value they present. The all black outfit also promotes a blending in that is impossible due to the brightness and “hype” around the shoes. However, the treatment of the person wearing the shoes is still largely the same: they are what they wear, and the reason that most people in the space would interact with them is due to the uniform they wear.

While the sentiment of drawing attention to the guards and the important job they play in the museum is honorable and well intentioned, it makes them part of the exhibition in an uncomfortable way. In a space where everything is for sale, many guards are accosted by sneakerheads looking to buy the shoes off their feet or the shirt off their back. This makes the guards seem like another commodity to be bought, especially because of the limited number and high value of the shoes they wear. Ultimately, this decision to have the guards wear exclusive designer shoes draws unwanted attention to museum workers who already have one of the hardest jobs in the museum space.

What does this mean for museums going forward? Is it a good idea to have special outfits for those that are working the key and popular exhibitions? To answer the first question, one need only look at the immense popularity of this exhibition. Whether this popularity is due to interest in Abloh or owning the merchandise, there is no denying that the sneakers are a major draw to the show. Having a piece of art or a specialty look that can only be observed by visiting the space draws people in, if for nothing else than to simply say “I saw it”. This exhibition has been reported in Cartter’s article and in the New York Times[4] as having lines that snake through galleries and people waiting outside before the museum opens so that they can be first into the space. There is an undeniable power in having something unique to set the exhibition apart from others, especially if it is a traveling show or a “highlights of the collection” show. Many museums are already capitalizing on the power of merchandise, with institutions like the Louvre and the Met partnering with fashion companies to produce limited run tees[5] or with brands like Casetify[6] to have limited run phone cases. In the world of fast fashion and renewed interest from consumers in owning art (partially thanks to Abloh), everyone wants to have a piece of the institution that can come home with them at the end of the day. Limited run exhibition merchandise that mirrors a specialty docent or guard uniform capitalizes on this excitement to own commercially available art. It could be a great way for museums to make revenue, much like Disney selling officially licensed costumes of its princesses – if someone wants to buy it and you can create the product for a price that benefits you as an institution, why not?

To

respond to the question about these specialty outfits and merchandise as a good

idea, the answer gets a bit murky. Museums can choose to run and market their

exhibits however they, their boards, and exhibition planners so please. There

are no other exhibitions to base this practice off of at the moment, but Figures

of Speech can act as a trial run for other museums looking to get in on the

publicity/merchandising opportunities. The exhibition is wildly popular and a

large enough draw to the public that Cartter and GQ were interested in

reporting on it, which is not something common for the magazine aside from

reporting on the material aspects of it (Met Gala looks, stores, objects that

people own). However, Figures of Speech should also act as a cautionary

tale to the museum looking to highlight its guards: there is a difference

between highlighting and isolating. In the case of this exhibition, the value

and inability to own the outfits draws unwanted attention, harassment, and

alienates the people that are there to make sure that the exhibition runs

smoothly and safely. Highlighting largely overlooked staff members is admirable

but making them part of the exhibit and putting people trying to do their job

on display is less so.

Works Cited

Cartter, Eileen. “The Story behind the Green Air Force 1s Virgil Abloh Made Exclusively for Museum Guards.” GQ. GQ, July 8, 2022. https://www.gq.com/story/virgil-abloh-brooklyn-museum-nike-guard-uniforms?fbclid=IwAR0Pv3vN5yhrWSk4PptZxFOuRGcRc5oY5lHSLi0Pk-H1IvzK2ZHeFw-HgTM.

Casetify. “Louvre.” CASETiFY. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.casetify.com/co-lab/louvre.

Casetify. “The Met.” CASETiFY. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.casetify.com/co-lab/the-met.

Lee, Anna Grace. “The Thirst for Merch.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 6, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/06/style/virgil-abloh-museum-merchandise.html.

“The Louvre × Yu Nagaba Special Site|the Louvre Museum(Musée Du Louvre) Partnership|Uniqlo.” UNIQLO. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.uniqlo.com/us/en/contents/feature/louvre-x-uniqlo/ut-collection/.

Wilson, Fred. “Fred Wilson:

Guarded View.” Fred Wilson | Guarded View | Whitney Museum of American Art.

Accessed November 16, 2022. https://whitney.org/collection/works/11433.

[1] Cartter, Eileen. “The Story behind the Green Air Force 1s Virgil Abloh Made Exclusively for Museum Guards.”

[2] ibid

[3] Wilson, Fred. “Fred Wilson: Guarded View.” Fred Wilson | Guarded View | Whitney Museum of American Art.

[4] Lee, Anna Grace. “The Thirst for Merch.” The New York Times.

[5] “The Louvre × Yu Nagaba Special Site|the Louvre Museum(Musée Du Louvre) Partnership|Uniqlo.” UNIQLO

[6] Casetify. “Louvre.” CASETiFY, Casetify. “The Met.”