Kubrick once said that the inspiration for 2001: A Space Odyssey came from a RAND Corporation report that deemed the universe as “crawling with life.” And so life comes to its first crawl in the outset of the film, these missing-link early hominids (often mistaken, somewhat erroneously, as apes) crouching, scrabbling, and, yes, crawling, around each other. In a letter to the film’s future co-screenwriter Arthur C. Clarke about his desire to create 2001, Kubrick outlined the two key strains of his interest in the project:

- The reasons for believing in the existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life.

- The impact (and perhaps even lack of impact in some quarters) such discovery would have on Earth in the near future.

If Malick’s film was an exercise in what life is not (Death? No life? After-life?), then perhaps Kubrick’s film is as well, though here it is unbound from the sort of “tree” imagery that tethered Malick’s film so closely to the terrestrial confines of this earth. For 2001 is about life beyond this planet, beyond even the globular space-structures the film has imagined for itself, space-structures cobbled together by the machines of men.

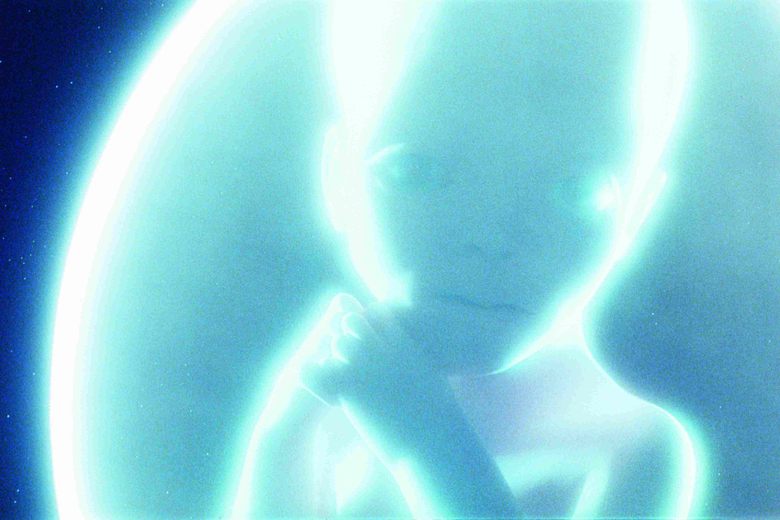

Clarke wrote to Kubrick that the image of Bowman, ejected from the escape pod, was “crawling with Freudian symbols, as you are doubtless aware.” It is clear from this turn of phrase that the embryonic imagery suffused throughout 2001 was intentional on the parts of both screenwriters. Watch as Bowman is forcibly thrust from the escape pod, thrust through an open air lock, and expelled into the void — Kubrick’s version of the Tree of Life scene in which a young Jack swims through a wooden-frame door, penetrating the softly rippling surface that separates Being from non-Being.

What does it mean to emerge from a state of pure maternal incorporation, to lift the corner of the veil, to float, become oneself? Malick frames birth as the emergence from the ocean, a firmly terrestrial (if altogether murky) depth — we already know, from his letters to Clarke, that Kubrick favors instead the image of extra-terrestriality, of a distinctly “human” life expelled from the site of technological enunciation (the space station). Bowman, called back into the void, this unsurvivable nothing/everything that we have only ever thought to call “space,” a word that can only invoke for us the idea of total absence. What does it mean to abandon the sum total of what we have deemed, ontologically speaking, the comprehensive framework of human knowledge?

Both Tree of Life and 2001 seek to frame the micro within the macrocosm, every birth and death a humble book-end to the much larger sprawl of universal being. There was a time before time, a time before the universe, before we had equipped ourselves with a comprehensive organizational framework (in which we developed the precise levels of hubristic — or possibly Kubristic — ambition, the technology to make a film in which we simply imagine what the advent of this universe might have looked like), and there will be a time after time, a time after the universe ceases to exist. Will that look like? Nothingness? Everythingness?

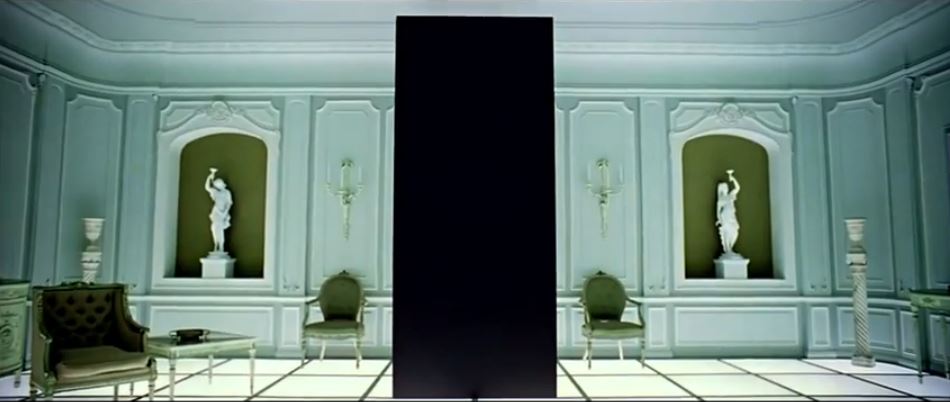

Perhaps it will look like a rectangular void that absences light, the monolithic conceit that so neatly bores a hole in the cinema screen.

The terror of death is existential, possibly blissful. Death is the “end.” But the end of what? The end of what we know? Of what we can imagine? Of what we can see? (That necessary sensation on which most all cinema is predicated) But then we have “been” through non-life before — before we were born, when we, like Jack in Malick’s Tree of Life, were swimming in the watery depths, bobbing ever closer to the surface.

So it stands that Kubrick, working in the paradigm of (what he would like to deem) “really good” science fiction, uses a piercing white light to paint the Star-Child, starlight being the provider of life in our universe, just as the projector-light is the life-blood of cinematic enunciation — and so this sublime (dare I say monolithic?) everything/nothingness must be represented as something beyond life itself — in fact, as something alien.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22263415/Scorcese_In_Taxi_Driver.jpg)