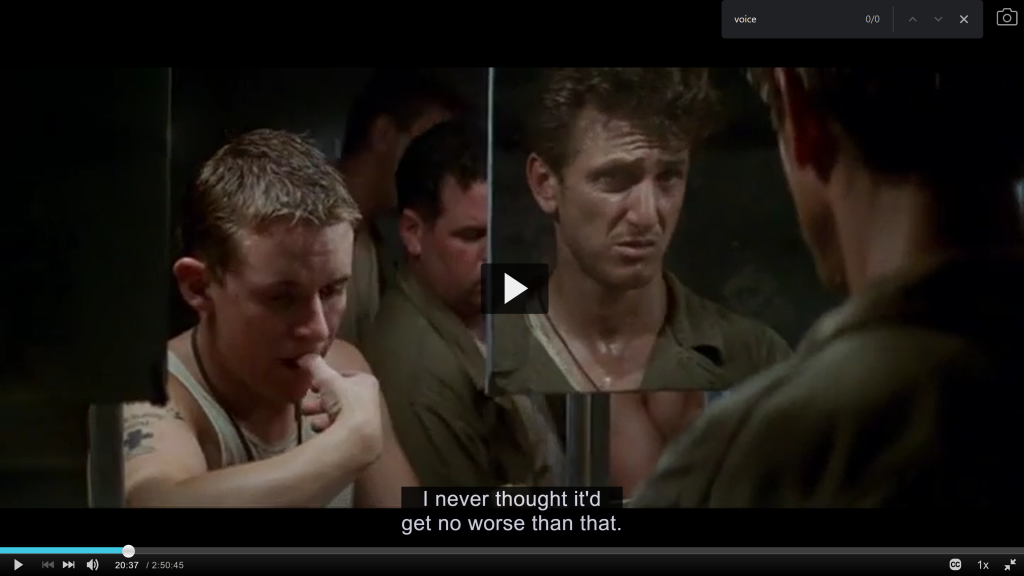

Edward Train speaks as The Thin Red Line begins, but the film takes some time to properly introduce him. Finally, the film shows Train in conversation with Welsh. Train describes his childhood fears.

As Train continues to speak, the camera wanders from his face.

This shot communicates disinterest in Train as an individual. The film further unravels this disinterest in an ironic sequence when it, after some shots of other soldiers, returns to Train.

As he expresses that “the war ain’t gonna be the end of me,” the camera shifts to obscure him.

In addition to again losing interest in Train’s face, the camera now emphasizes Train’s mortality and how easily the film can destroy it.

In contrast to its disinterest in Train as person, the movie is clearly interested in Train as voiceover narrator. Drawing on the work of sound theorist Michel Chion, academics Clint Stivers and Kirsten Benson identify Train’s voiceover as a “spectral presence” that “[crosses] space and time”, affects on-screen action from somewhere else, and is in possession of powers like “omnipotence”. In sum, a god.

The film’s treatment of Train plays into a larger pattern. The Thin Red Line lumps soldiers together with camerawork and costuming, yet pays respect to Malick’s distinctive directorial style. These patterns play into the human fears that viewers may bring to their screenings. The fear that if someone made a movie about them, it wouldn’t capture their individuality. The fear that their reactions as viewers are indistinctive. The fear that they matter less than their voice; than God.