By Martha Pott

“Where were you in camp?” I was standing next to my friend, Hiroshi (David) Yamamoto, who had just been introduced to someone who was also Japanese American. They weren’t talking about summer camp. Hiroshi was four years old when his family was interned at Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, where he lived with his parents and two older sisters until he was eight.

After Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 that incarcerated people of Japanese descent in internment camps in the western US in an effort to “curb potential Japanese espionage.” Those who were identified as at least 1/16th Japanese were given 6 days to dispose of their property and possessions. In fact, there were no charges ever brought against Japanese Americans for espionage or sabotage against the United States. Most of those interned were US citizens. Over half of those interned were children. In 1980, the US government established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), which concluded that Executive Order 9066 “was not justified by military necessity” but was driven by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and failure of political leadership.”

This photo shows the Mochida family in Hayward, California, waiting for a bus that will “evacuate” them to an “assembly center” and, eventually, a “relocation center. “The US government used identification tags “to aid in keeping the family unit intact during all phases of evacuation.” The father, Mr. Mochida, ran a nursery with five greenhouses, raising snapdragons and sweet peas.This photo shows the Mochida family in Hayward, California, waiting for a bus that will “evacuate” them to an “assembly center” and, eventually, a “relocation center. “The US government used identification tags “to aid in keeping the family unit intact during all phases of evacuation.” The father, Mr. Mochida, ran a nursery with five greenhouses, raising snapdragons and sweet peas.

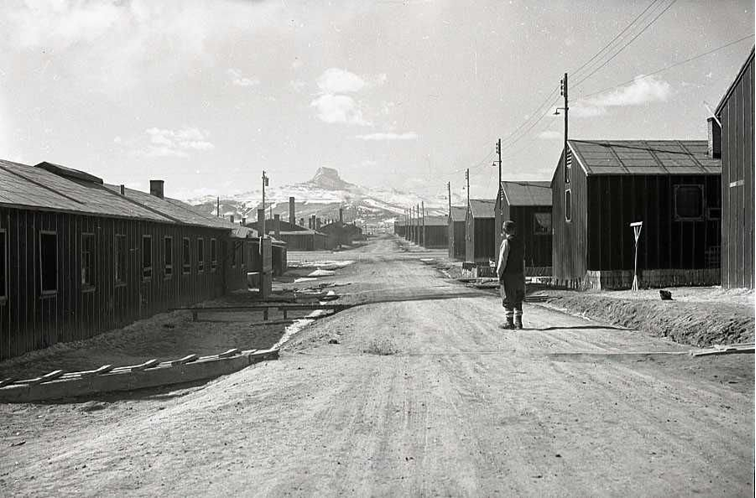

David was the youngest child when he and his family were forced to leave their strawberry farm and home in San Jose, California and were sent to Heart Mountain, Wyoming, named for the mountain in the distance shaped like a heart. Originally part of the Apsáalooke (Crow) tribe homelands, the Heart Mountain Relocation Center was one of 10 camps that incarcerated 120,000 Japanese Americans in the west. Heart Mountain held 11,000. David’s family lived in drafty barracks surrounded by tall barbed-wire fences patrolled by armed military police. David and I visited Heart Mountain in 1981 on a camping trip where we found the barracks and laundry still standing, and a US historical marker indicating that people were “loosely confined” there during the war, that the camp was “equipped with modern waterworks and sewer system and a modern hospital and dental clinic,” and that “first rate schooling was provided….” This isn’t the way many remember it.

I recently wrote to David to ask him to reflect on that experience. He first told me that most now use the term “incarceration center” rather than “relocation camp” or “evacuation camp.” Then, he wrote: “Our family splintered under the weight of incarceration. My mother spent much of the time in the hospital. This necessitated my 12-year-old sister to be the surrogate mother to two younger siblings, a responsibility she greatly resented. My father left the family to work on the railroad to raise funds…. Unknowingly I internalized all the stress, struggles and angst arising from how our family reacted to the incarceration.… [I]t took me the vast majority of my adulthood to understand and address unhealthy and negative consequences that subtly and not so subtly defined me.” David went on to say, “Not all is/was negative. Because of my background I am sensitive to racial and ethnic injustice and discrimination.”

Since David and I visited Heart Mountain, some things have changed. A new historical marker indicates more accurately what really happened there (see photo below). A Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation has been established with a mission to preserve and memorialize the site and the “stories that symbolize the fragility of democracy,” to educate the public, and to support the preservation of liberty and civil rights for all Americans today.

But some things haven’t changed. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism reports that anti-Asian hate crime in the largest cities and counties in the US rose by 164% in the first quarter of 2021 compared to the same time period in 2020 (Pew Research Center). In response, President Biden signed into law the bipartisan COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act. Among many goals, the new initiative is charged with advancing equity, justice and opportunity for Asian American and Native Hawaiian Pacific Island communities with a comprehensive federal response to the rise of anti-Asian bias and violence. February 19 was a Day of Remembrance of Executive Order 9066.

Martha Pott is a faculty member in the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study & Human Development.

ABOUT

ABOUT