The Garifuna People

The Garifuna people, also known as Garinagu, refer to a diaspora of Indigenous Caribbean people descended from the Arawak, African, and Carib peoples,1 According to oral tradition, a slave ship was wrecked on the coast of St. Vincent where intermarriage then occurred between the African slaves and the indigenous Arawak and Carib peoples. The story of the Garifuna people is one with a rich history of spirit and resilience in the face of settler-colonial powers. As British soldiers and settlers encroached on their land, the Garifuna people waged war under Chief Joseph Chatoyer, until his death in 1795. After two more years of decentralized resistance, the remaining Garifuna rebels were exiled by the British from St. Vincent. Those who survived the voyage landed on the Island of Rotan, eventually establishing roots in Honduras and Belize.

Today, the majority of the Garifuna diaspora is scattered throughout Belize, Honduras, and North America. Without a distinct homeland, Garifuna have struggled to retain their cultural practices. In the documentary The Garifuna Journey, one Garifuna elder explains, “It is during the long journey that we rearrange our burden, we want to make much of our Garinagu children, we want them to learn their language…we want them to learn their culture. They are putting down their culture, most of them, so that is our burden now.” 2 Indeed, as expatriates from the United States retire in the Caribbean, and the tourist industry continues to encroach on indigenous land, the risk of displacement and cultural extinction looms larger than ever. Unfortunately, many Central American governments continue to increase protections for industry over indigenous land rights. The 107th amendment to the Honduras constitution, which had previously prohibited land sale to foreigners, was amended in 1998 to make an exception for the tourism industry. 3 Similarly, in 2004, new property laws were implemented in Honduras which allowed for the dissolution of communal land titles (such as those held by Garifuna). 4 More recently, in 2011 the Honduran government supported Banana Coast Cruise development which dispossessed Garifuna from community lands in Rio Negro. 6 Despite the pressure from many directions to surrender their property, Garifuna continue to strengthen their cultural bonds, and in doing so, maintain their historical and spiritual ties to their land.

For Garifuna, music is integral to the retention of culture. Music weaves a common thread throughout the diaspora, bringing communities together in a shared language, dance, and rhythms. The musical genres of punta and paranda date back to Garifuna’s origins in St. Vincent. 6 During the widely celebrated Garifuna Settlement Day, punta and paranda are often heard, along with traditional dances and stories.

Punta Rock

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, there was a period of mass Caribbean migration to the United States, specifically for parents in search of better employment opportunities. This left a gap in generational knowledge, and many young people began to disavow their language and culture. It is within this context that the genre of punta rock emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. A fusion of hip hop, rock, and traditional punta, to some, punta rock’s use of synthesized keyboards and drum machines symbolized a movement away from tradition. However, the duple-meter rhythms that underlay punta rock are indistinguishable from the traditional beats of punta. As ethnomusicologist Oliver N. Greene writes, “For the Garinagu, modernity and the subsequent creation of punta rock did not involve the “shedding of tradition” but rather the maintenance of indigenous Garifuna proverbial ideals through the transformation of a traditional genre of musical expression.” 7 Punta rock’s revolutionary use of traditional elements has encouraged new generations of artists, across genres, to incorporate Garifuna cultural traditions into their work.

Andy Palacio (1960-2008)

Few have embodied the spirit of punta rock like Belizean musician Andy Palacio. After growing up in the coastal village of Barranco, Belize, Palacio was called to music following a visit to a Garifuna community in Nicaragua. 8 In Palacio’s own words,

“What I saw was a generation of Garifuna people who no longer knew how to speak our language in such a way that nobody under the age of 50 was able to communicate with me in our language, and music being the thing that I love most I decided to use music as a medium for cultural preservation.” 9 His album Wàtina (I Called Out), focuses on themes of culture, family, and land. In a 2007 interview with NPR Host Melissa Block, Palacio describes his effort to use music as a medium for cultural preservation. 10 His efforts to preserve Garifuna culture have not gone unnoticed. In 2004, Palacio was invited to serve as Belizean Cultural Ambassador at the National Institute of Culture and History. He then went on to win the title of UNESCO Artist for Peace. 11

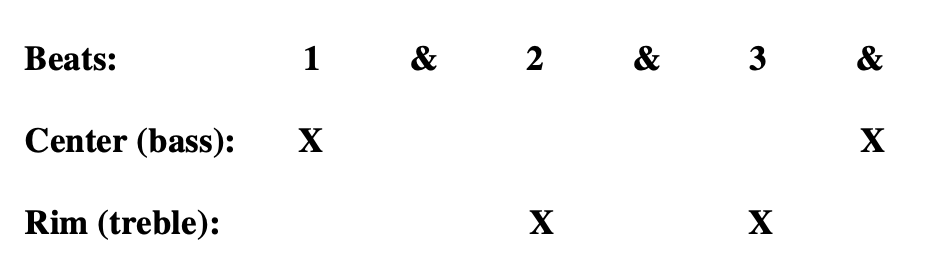

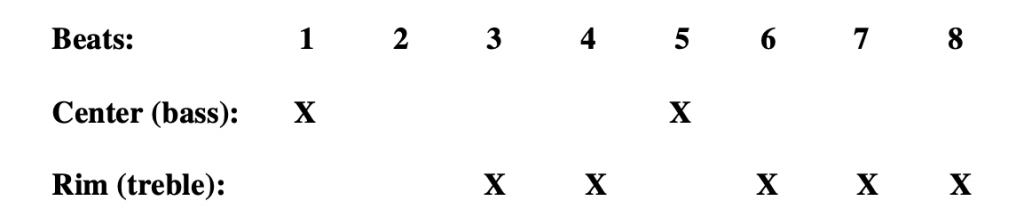

Despite his roots as a punta rock musician, Wàtina bleeds into the interdependent genre of paranda music, punta’s slower and more soulful twin. The album’s most identifiable rhythms are the Hünguhüngu, consisting of three beats, and Gunjai, consisting of eight beats.

Images and information courtesy of Amy Lynn Frishkey. 12

“Miami” on Wàtina centers Miami, Honduras, a location known for its scenic beach fronts. In Palacio’s own words

“Miami refers to the current situation of land tenure within the Garifuna community where the community has come face to face with encroachment on lands traditionally held by Garifuna people which is now being opened up and sold to wealthy land interests for tourism development. And all of a sudden people find themselves being excluded from lands that they previously had unlimited access to. And one such area is a beach in Honduras that they refer to as Miami Beach–and the song is about that situation.” 13

The Umalali Women’s Collective

The Umalali Women’s Collective consists of Bernandine Flores, Chella Torres, Damiana Gutierez, Desere Diego, Elodia Nolberto Fernandez Guity, Julia Nunez, Marcelina Masagu, Sarita Martinez, Alva Arana, Marcela Arana, Silvia Blanco, and Sofia Blanco. 14

Towards the end of his life, Andy Palacio and Wàtina producer Ivan Duran collaborated in order to bring together the Umalali (or voice) collective. In 1997, Duran began traveling to Garifuna communities across Belize, researching local cultures, interviewing women, and recording music. 15 After about ten years of research and recording, the Umalali Women’s Collective was born.

Umalali is a framework which showcases the raw talent of the Garifuna women who, for centuries, have acted as stewards of Garifuna song and culture. Cultural authenticity was central to this project in which most women had little experience with recording studios or performing on stage. 16 Duran even recorded portions of the album in more culturally organic settings like living rooms, kitchens, or temples. 17 Intergenerational by nature, many songs are intimately connected to the singer’s family and may be written by their mothers, grandmothers, or other relatives. The group even includes a mother-daughter duo, Sofia and Sylvia Blanco. 18 The songs of Umalali are deeply intimate, brimming with love, longing, and loss. The music often takes on a darker, more bluesy tone than punta rock, accompanied, of course, by the drum rhythms that structure Garifuna music. 19

In the song “Uruwei” (The Government) Bernadine Flores sings a song composed by her grandmother, Ola. In her lyrics, Bernadine refers to her children, Isabel and Nicho.

Anihan uruwei ya aü lahayahen nege lau le lisien

Nahayaruba gien bomou

Nahayaruba, wanwa, luba gudemetina

Haliyoun nibadina baume, Nicho

Haliyoun nibadina baume wanwa

Haliyoun nibadina beiba wabien

Haliyoun nibadina baume Isawelu

Haliyoun nibadina baume wanwa

Haliyoun nibadina beiba wabien

Haliyoun nibadina baume, nirau

Haliyoun nibadina baume, wanwa

Haliyoun nibadina beiba wabien

The government is here, hiring out of love they say

I will get a job

I will get a job for I am poor

Where shall I take you, Nicho

Where shall I take you, my dear

Where shall I take you? You had better go home

Where shall I take you, Isabel

Where shall I take you, my dear

Where shall I take you? You had better go home

Where shall I take you, my son

Where shall I take you, my dear

Where shall I take you? You had better go home

In this interview, Desere Diego, who is heavily featured on the album, touches on her origins as a singer and goals for the future.

Works Cited:

- Andrea E. Leland, Kathy Berger, The Garifuna Journey (New Day Films, 1998), https://tufts.kanopy.com/video/garifuna-journey.

- Ibid.

- Nicole Thornton, “Whirlwind Legislature Threatens Garifuna Lands,” Cultural Survival, Mar. 1, 1999, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/whirlwind-legislature-threatens-garifuna-lands.

- Sharlene Mollett, “A Modern Paradise: Garifuna Land, Labor, and Displacement-in-Place,” Latin American Perspectives 41, no. 6 (2014): 27–45, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24573989.

- Keri Brondo, “A Dot on a Map”: Cartographies of Erasure in Garifuna Territory, PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 41 (2018): 185-200, 10.1111/plar.12272.

- Oliver N. Greene, “Ethnicity, Modernity, and Retention in the Garifuna Punta,” Black Music Research Journal 22, no. 2, University of Illinois Press (2002):189–216, https://doi.org/10.2307/1519956.

- Ibid

- Jon Pareles, “Andy Palacio, Who Saved Garifuna Music, Dies at 47,” The New York Times, Jan. 21, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/21/arts/music/21palacio.html.

- Melissa Block, “Musician Andy Palacio of Belize Dies at Age 47,” NPR, Jan. 21, 2008, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=18287881.

- Ibid.

- “UNESCO Chief Pays Tribute to Belizean Musician, Artist for Peace,” UN News, Jan. 22, 2008, https://news.un.org/en/story/2008/01/246552-unesco-chief-pays-tribute-belizean-musician-artist-peace.

- Amy Lynn Frishkey, Garifuna Popular Music “Renewed”: Authenticity, Tradition, and Belonging in Garifuna World Music (University of California, Los Angeles), https://www.proquest.com/docview/1830466712/abstract/E6610E7B9ECD4217PQ/1. Accessed Feb. 14, 2022.

- Oliver Greene, The Garifuna Music Reader. (Cognella Academic Publishing, 2018): 331.

- Ivan Duran, Liner notes, Umalali: The Garifuna Women’s Project, Stonetree Records, 2007, compact disc.

- Tom Pryor, “Off the Beaten Track: Umalali – “the Garifuna Women’s Project,”Sing Out! The Folk Song Magazine (Summer 2008): 120.

- “Umalali & the Garifuna Collective,” WOMEX, Piranha Arts AG,

- “Umalali,” Stonetree, Stonetree Records, http://www.stonetreerecords.com/music/umalali/.

- Jon Kertzer, “Umalali: The ‘Voice’ Of The Garifuna,” NPR, Jan. 27, 2009, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=99877936.

- C. C. Smith, “Andy Palacio: The Pride of the Garifuna,” The Beat (2008). Accessed April 3, 2022.