Slack Key and the Second Hawaiian Renaissance

The Second Hawaiian Renaissance refers to an energetic political and cultural movement of rebirth in the late 1960s and the 1970s. Politically, the Second Hawaiian Renaissance was a site for grassroots resistance against United States imperialism. Following statehood in 1959 and assimilatory policies imposed throughout the 1960s, many Indigenous Hawaiians responded through organized political resistance. At the forefront of these battles was the retention and protection of Hawaiian land. Some of the formative land battles of the Second Hawaiian Renaissance were the Kalama Valley farmer’s protests in 1970, which sparked decentralized community movements around Hawaii. At the crux of the movement was the Protect Kaho’olawe Ohanaland (PKO) campaign. Kahoolawe is a site of immense spiritual and cultural significance in Hawaiian culture. Despite the land’s history, it was officially delegated to the U.S. Navy by an executive order from President Eisenhower in 1953. As a military site, the land was regularly used to test explosives, endangering its natural resources. In 1976, the PKO was formed, a figurehead of Native Hawaiian resistance, which fought for Hawaiian sovereignty over the land 1 . Over time, the PKO came to be an important political figurehead of the Second Hawaiian Renaissance.

Culturally, this movement renewed excitement surrounding Hawaiian cultural tradition, including music, dance and language. George Kanhele, who coined the movement’s name, described it in the Honolulu Advertiser as a resurgence of Hawaiian culture which was “articulate, organized, but unmonolithic.” 2 New institutions of cultural education sprung up throughout Hawaii, such as the number of hälau hula or schools that teach traditional Hawaiian dance and chant. The organization ‘Aha Pūnana Leo formed in 1983 also had a tremendous impact, establishing Hawaiian language immersion preschools throughout Hawaii. 3 These institutions ensured the continued practice of Hawaiian culture despite increasing settler presence.

Music played a critical role in shaping the politics, interactions, and spirit of the Second Hawaiian Renaissance. At times, protest songs represented a particular campaign by playing at rallies and events, such as Mele O Kaho`olawe, which was the unofficial anthem of the PKO land battle. In another sense, music served as a spiritual and emotional framework for indigenous Hawaiians, as it has for centuries. Unsurprisingly, the music of the Hawaiian Renaissance largely drew from older Hawaiian musical tradition. Music was usually sung in the Hawaiian language, sometimes reconfiguring lyrics from older songs. During the movement, slack key (ki ho’alu) also re-emerged as a dominant musical genre. 4 Slack key’s roots in Hawaii date back to the reign of King David Kalākaua, who spearheaded the first Hawaiian renaissance in the late nineteenth century. Groups like the Sons of Hawaii, Sunday Manoa and Mākaha Sons of Niʻihau played a vital role in the revival of slack key. In 1973, the resurgence of slack music was augmented by the publication of the first slack key method book by Keola Beamer. The revival of slack key was anti-colonial at its core. As Kevin Fellezs writes, slack key during the second Hawaiian Renaissance can be considered as “a sonic challenge to settler colonialism, and one possibility for rethinking the way Hawaiians’ “soft, appealing sounds” can signal defiance rather than acquiescence, sounding out and articulating indigenous agency rather than native victimization or nostalgic indulgence.” 5

While the return to slack key was largely associated with tradition, it was reinterpreted within the modern context. For example, newer strings like the tiple and requinto were integrated into slack key music. Slack key artists drew upon traditional percussion like the ipu (Gourd Drum), ʻili ʻili (smooth black stones), and pahu (sharkskin drum) in new ways. 6 Players like like David “Feet” Rogers also experimented with new tuning styles for the steel guitar.

The Sons of Hawaii

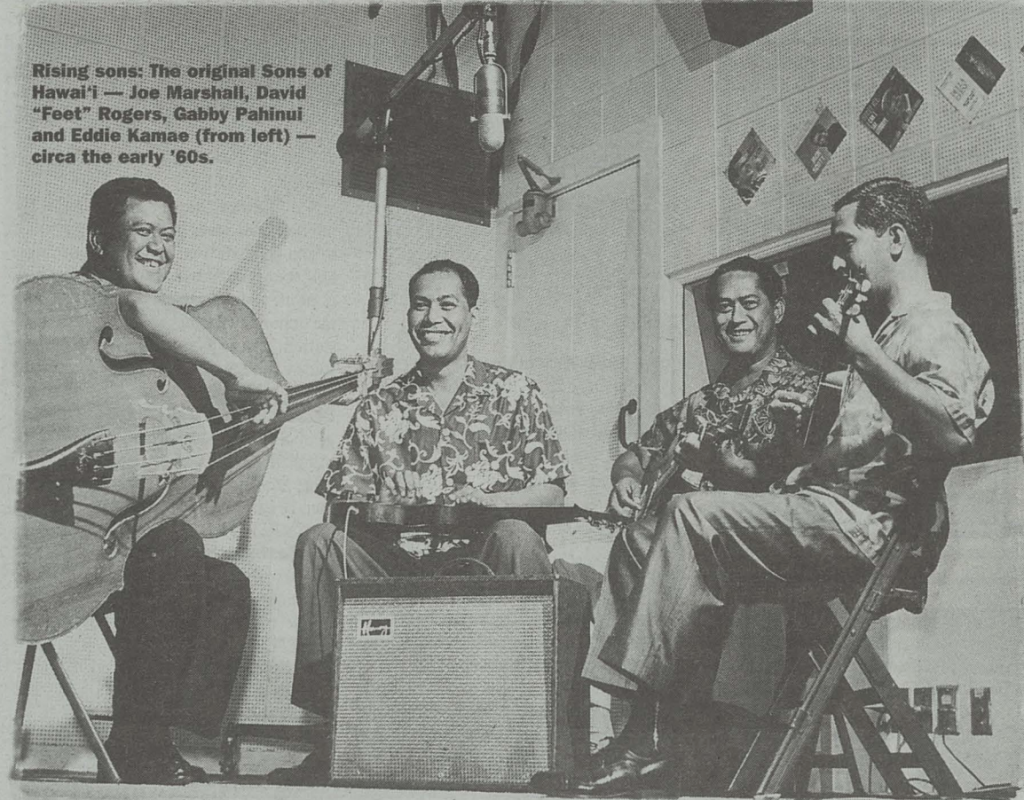

At the center of the Hawaiian Renaissance were Gabby Pahinui and the Sons of Hawaii. Pahinui, who specialized in the slack key genre, began creating and releasing music in the 1940s and 1950s, but grew to legend status during the Hawaiian Renaissance. Pahinui renewed excitement for the slack key genre, and inspired future generations of Hawaiians to pursue slack key. The group, assembled by Pahinui, made their debut in 1959 at the O’ahu sandbox. Although many iterations of the group evolved over time, the original Sons of Hawaii consisted of Gabby Pahinui, Eddie Kamae, Joe Marshall, and David “Feet” Rogers. In order to produce their music, the Sons of Hawaii looked to Hawaiian elders for help. Mary Kawena Pukui, Hawaiian scholar, musician, and cultural preservationist, was a particularly formative influence, inspiring the band with traditional Hawaiian music and histories. The Sons had a massive following of rural, elder, and working class Hawaiians. 7 DaCarl Linquist, co-producer of the Hana Ho’olaule’a at Hana Maui festival described the Son’s performance there, saying, “I think that was the first time we realized that it could be traditional Hawaiian music but done in a brand new way, and yet still honoring the language and the traditions that we all love.” 8 The music produced by the Sons of Hawaii was referred to as ku a’ aina, or grassroots music.

In 1971, the Sons of Hawaii released the landmark album The Folk Music of Hawaii, known colloquially as the Red Album or the Five Faces Album. It included an illustrated book about the band and where they came from. The album relies heavily on the ukulele as the primary rhythmic instrument, in Kamae’s style. 9

Liko Martin

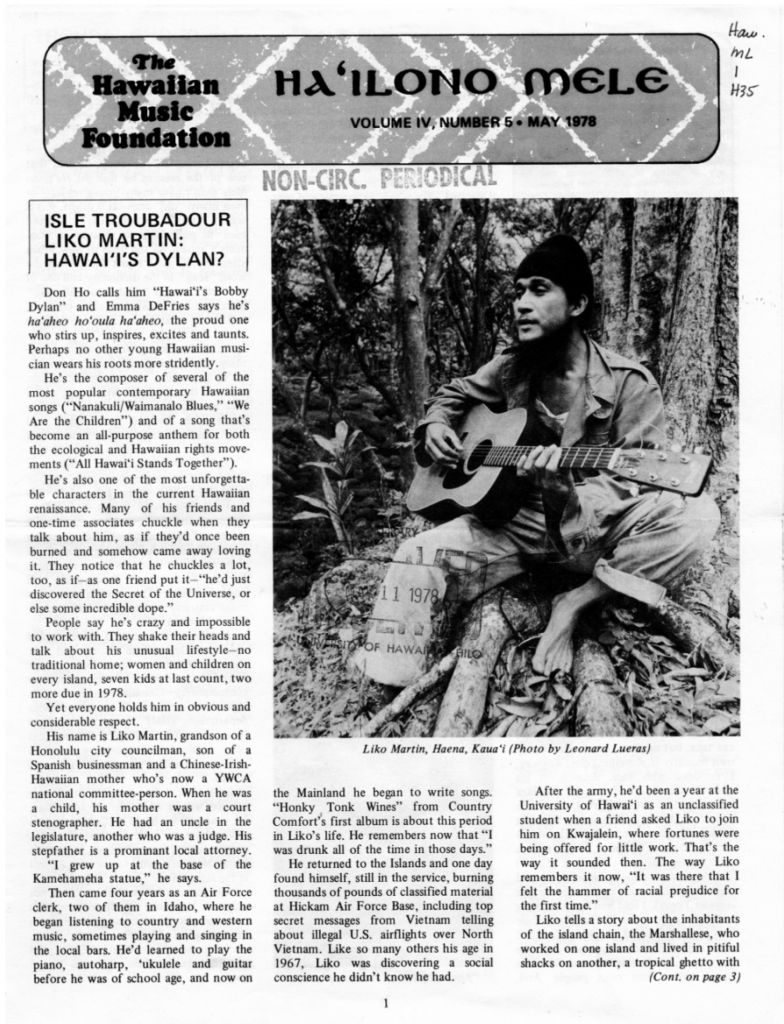

Another influential slack key artist who came to define the Second Hawaiian Renaissance was Liko Martin. Often compared to Bob Dylan, Martin’s music is a brilliant mixture of traditional Hawaiian folk instrumentals and politically-infused lyrics. Martin spent his formative years as an Air Force Clerk, and at the University of Hawaii during which he practiced the guitar, ukulele, autoharp and piano. After leaving the air force, Martin soon met the band Country Comfort from Waimanalo, and the group released an album. On this record was a collaboration with Thor Wold entitled “Nanakuli Blues,” (Changed later to Waimanalo Blues) Martin’s first major hit 10

Wind's gonna blow so I'm gonna go

Down on the road again

Starting where the mountains Ieft me

I'm up where I began

Where I will go the wind only knows

Good times around the bend

Get in my car, goin' too far

Never comin' back again

Tired and worn I woke up this mornin'

Found that I was confused

Spun right around and found I had lost

The things that I couldn't lose

Chorus:

The beaches they sell to build their hotels

My fathers and I once knew

Birds all along sunlight at dawn

Singing Waimanalo blues

Down on the road with mountains so old

Far on the country side

Birds on the wing forget in a while

So I'm headed for the windward side

Au of your dreams

Sometimes it just seems

That I'm just along for the ride

Some they will cry because they have pride

For someone who's loved here died

The beaches they sell to build their hotels

My fathers and I once knew

Birds all along sunlight at dawn

Singing Waimanalo blues

This song, like many others written by Martin, touches on Indigenous Hawaiians’ relationship with land, increasingly threatened by United States private corporations and the tourism industry.

Martin continued to be politically outspoken during the Hawaiian Renaissance as he became enmeshed in the PKO land battle as a singer-songwriter and activist. During his time with the PKO, Martin produced his famous anthem “All Hawaii Stands Together.”

Works Cited:

- Mansel G. Blackford, “Environmental Justice, Native Rights, Tourism, and Opposition to Military Control: The Case of Kaho’olawe,” The Journal of American History 91, no. 2, (2004): 544–71, https://doi.org/10.2307/3660711

- George H. Lewis, “Da Kine Sounds: The Function of Music as Social Protest in the New Hawaiian Renaissance,” American Music 2, no. 2 (University of Illinois Press, 1984): 38–52, https://doi.org/10.2307/3051657.

- Davianna Pōmaika‘i.McGregor, “Kaho‘olawe: Rebirth of the Sacred,” Na Kua`aina: Living Hawaiian Culture (University of Hawai’i Press, 2007): 249–85, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wr2zc.9.

- George H. Lewis, “Style in Revolt Music, Social Protest, and the Hawaiian Cultural Renaissance,” International Social Science Review 62, no. 4 (Pi Gamma Mu, International Honor Society in Social Sciences, 1987): 168–77, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41881768.

- Kevin Fellezs, “Nahenahe (Soft, Sweet, Melodious): Sounding Out Native Hawaiian Self-Determination,” Journal of the Society for American Music 13, no. 4 (Cambridge University Press, 2019): 411–35, https://doi.org/10.1017/S175219631900035X.

- Lewis, “Style in Revolt Music, Social Protest, and the Hawaiian Cultural Renaissance,” 168–77.

- George H. Lewis, “Storm Blowing from Paradise: Social Protest and Oppositional Ideology in Popular Hawaiian Music,” Popular Music 10, no. 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1991): 53–67, http://www.jstor.org/stable/853009

- Eddie Kamae, The History of the Sons of Hawaii (Hawaiian Legacy Foundation, 2000)

- Jim Tranquada and John King, “The Growing Underground Movement,” The ‘Ukulele: A History (University of Hawai’i Press, 2012): 153–66, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqm6h.13.

- Hopkins, Jerry. “Isle’s Troubador Liko Martin: Hawai’i’s Dylan?” Ha’ilono Mele 4, no.5 (May 1978): 1.

- “Official Waimanalo Blues Lyrics, 2022 Version.” LyricsMode.com, March 27, 2012. https://www.lyricsmode.com/lyrics/d/don_ho/waimanalo_blues.html.