Happy New Year, everyone!

There’s a lot of motivation flowing at the beginning of a new year (and, in this case, a new decade!) to set goals — and subsequently crush them. Most often, I quickly find that my dedication to stick with whatever harebrained New Year’s resolution I may or may not have come up with is waning (exponentially decaying with a half-life of about 4.5 days, resulting in only 1% of my original motivation still present and accounted for at the end of January). And while my resolutions have typically focused on personal development, this year I’m turning my attention to the lab.

As graduate students, we’re often spread thin, what with trying to get our experiments done, train new students, and meet with our advisors. Add to that taking classes (at least in your early years), keeping on top of the literature, creating your own literature, and networking, and it’s a wonder that any of us have time to focus on things other than our degrees. What are we to do when we want to set goals and make sure we achieve them?

I was musing over how to write this article over dinner with a friend one evening when she mentioned S.M.A.R.T. criteria. While I’d heard of this acronym before, I never knew exactly what it meant, or how I was supposed to apply it, until she explained it to me. It makes a whole lot of practical sense, so I’m going to pay it forward and share it all with you, in case you were similarly unaware of its meaning and potential.

S.M.A.R.T. criteria were first introduced by George Doran in 1981 (1). In the article he published, Doran states that objective should be [(quoted)]:

Specific – target a specific area for improvement.

Measurable – quantify or at least suggest an indicator of

progress.

Assignable – specify who will do it.

Realistic – state what results can realistically be achieved,

given available resources.

Time-related – specify when the result(s) can be achieved.

Keep in mind that this article was originally meant for managers with a team. Other sources and articles on S.M.A.R.T criteria use other words (e.g. “achievable” in place of “assignable” and “relevant” instead of “realistic”) (2). For graduate students, using “achievable” might be more realistic than “assignable,” since, unless we’re managing another student, we’re going to “assign” the work to ourselves.

Let’s set an example goal, say, reading more of the literature in a particular field. How can we make this into a S.M.A.R.T. goal? For each letter in the acronym, there will be a list of things to consider and refinement of the goal to include the necessary information.

Specific

Consider the goal, who will be involved, and what your motivation is.

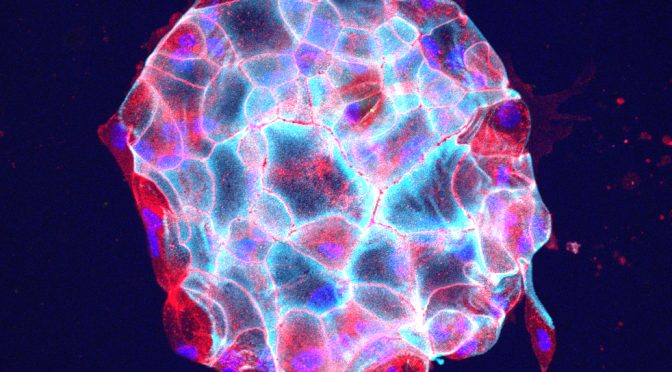

“I want to read more papers to gain a better understanding of the role of Wnt signaling in cancer.”

Measurable

How can this goal be quantified? How will you know if you’ve made progress?

“I want to read 20 papers to gain a better understanding of the role of Wnt signaling in cancer.”

Assignable/Achievable

For graduate students, reading 20 scientific journal articles is certainly an achievable goal. So we get a checkmark here!

Realistic/Relevant

Consider what resources are available to help you achieve this goal. Is this goal relevant to your overall objectives (earning a graduate degree)?

“Using journal access provided by the university library, I want to read 20 papers to gain a better understanding of the role of Wnt signaling in cancer.”

Time-related

Consider what your deadline is (perhaps you’re writing a review article on Wnt signaling and a section on cancer will be included) and whether it is realistic.

“Using journal access provided by the university library, I want to read 20 papers by June 15th to gain a better understanding of the role of Wnt signaling in cancer.”

Consider this article as a starting point when setting goals. The nice thing about S.M.A.R.T. is it gives you an achievable goal to go after, but the bad thing is it puts you in a structured box, which can prevent you from taking some bigger risks that could really pay off! It’s important to know when your goals need to be more flexible than S.M.A.R.T. criteria allows them to be, but if you, like me, find yourself getting frustrated for setting goals and not achieving them, this may be a good place to start.

References:

1. Doran GT. (1981) There’s a S.M.A.R.T way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review 70(11):35-36.

2. https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/smart-goals.htm