Riot

Disclaimer

Although riots can be studied through various lenses, this paper will focus specifically on riots in relation to race. Additionally, seeing as our personal experience and understanding of riots are most deeply rooted in the United States, our analysis will be based on a national level.

Gonzalez, Carlos. BLM 2020 Minneapolis Riot Image. Star Tribune. Getty Images, June 2020.

Definitions

“A tumultuous disturbance of the public peace by three or more persons assembled together and acting with a common intent.”

Merriam-Webster [1]

“…the term ‘riot’ means a public disturbance involving (1) an act or acts of violence by one or more persons part of an assemblage of three or more persons, which act or acts shall constitute a clear and present danger of, or shall result in, damage or injury to the property of any other person or to the person of any other individual or (2) a threat or threats of the commission of an act or acts of violence by one or more persons part of an assemblage of three or more persons having, individually or collectively, the ability of immediate execution of such threat or threats, where the performance of the threatened act or acts of violence would constitute a clear and present danger of, or would result in, damage or injury to the property of any other person or to the person of any other individual.”

Federal law 18 USC Ch. 102: RIOTS [2]

“The focus here is on crowd behavior generally and violent crowd behavior in particular. Attention is paid in the main to those events that appear to have been successfully defined as riots; that is, outbreaks of violence that are regularly described in this way not just by government officials and the police but by other observers including social scientists.”

tim newburn [3]

Although deceptively simple, the term riot holds countless interpretations, varying amongst person to person, as demonstrated above. Yet, most of these descriptions fail to acknowledge the deeper concepts intertwined with the term itself. Riots are often heavily racialized and politicized, influenced by methods and systems masked from the public view. The term is commonly associated with a negative connotation, linked to violence and chaos, especially when compared to its counterpart, protest, which carries an air of positivity and peace. Yet, the situations these terms describe are noticeably more similar than different, making it interesting to treat them as labels used to brand an overarching event type. Our goal is not to attempt to establish a single definition for riot, but rather to explore its application.

Patterns: How Riots Come to Be

Despite the ambiguity and flexibility of the term itself, scholars of American, African-American, and Ethnic Studies tend to converge in their understanding of the conditions that set the stage for a riot to occur. In a backdrop of slow, unsteady improvement in a social cause or campaign, riots act as sharp points of confrontation where the movement faces its lack of progress. Part of understanding what riots are is understanding the conditions that cause them. Sometimes, riots are reactions to specific trigger events, such as police shootings, civil disobedience, and so on. However, these events can spark a riot because of the heightened tensions already present in the community where the riot takes place. Other times, riots are reactions to ongoing issues and have no galvanizing event; the motivating factors are more subtle, such as a lack of progress, frustration at social structures and systems, or systemic inequality.

A riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear? … It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met.

dr. Martin luther king, jr. [4]

One of the first major evaluations of riots in the US came from the 1968 Kerner Commission, a report ordered by President Lyndon B. Johnson to investigate the causes of an outbreak of riots that swept Black communities in the 1960s. This report is monumental because it was the first time the country writ large acknowledged that riots aren’t simply violent outbursts but are frustrated reactions to real issues [5]. Among other elements, the report found that “pervasive discrimination,” “frustrated hopes of Black folk,” and “the culture of poverty” were likely the galvanizing factors [6]. The structures of racism and classism were what triggered the riot, not a random outburst of a violent group of individuals, as scholars and the general White public alike had previously thought.

Generally, the structure of a riot can be boiled down into six phases, taking place along a timeline. In the video below, PBS’s The American Experience educational series addresses these phases and names them: below the surface, breaking point, protests, police escalation, media coverage, and fallout. In the examples later in our discussion, tracing these phases can help interpret each event, no matter how specific the cause is.

Protest vs. Riot

In June 2020, Anderson Paak released “Lockdown”, a song speaking to the protests and social uprising taking place in response to the murder of George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police Department. His death was a catalyst for consciousness and action, partly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and viral footage of the murder. His death is one of many, in a hundreds years long history of white supremacist US police brutality against Black men, women, and children.

In the song there are both direct and indirect references to the idea of riots. The first direct reference is about the police. Anderson Paak raps “riot cops tried to block, now we got a showdown.” Later, in Jay Rock’s verse, he uses riot in a different sense when he says “ready for the revolution, who ready to riot?” [7] Their lyrics raise the question of whether riots and protests can be defined as two separate types of events. For our purposes, we are attempting to understand the two concepts as labels which are applied by the people, the state, and the opposition, with the intent of controlling the narrative through the connotations and bounds of each term, respectively. The language chosen for the narrative can have large implications for legal, public, and social responses, as we will see in the examples explored later. It is crucial to note that not only is this language applied, as opposed to chosen, it is often exercised after the event has taken place. The application of these labels is a politicized and racialized process.

We are not trying to solidify what a riot is by solidifying what a protest is. Rather, we see riots and protests as labels that are applied to an event. We can understand the meaning of these terms through the reactions to instances of their application. Protests and riots exist in direct connection to one another, which can be simplified as two ends of a spectrum. Where one draws the line on the spectrum, dividing the two terms, is ultimately an arbitrary choice. One of the factors which greatly impacts the relationship between the two terms is the perceived spectrum of intensity of the event, intensity which often correlates with violence, which can also take on different definitions. The actions of Black and brown people are far more likely to be seen as violence or driven by anger, by the public and state who view them through a lens of white supremacy. Riot is applied to the actions of a group of people when they are seen as escalatory and combative. Consider the cases when riot cops have been deployed against the people. When riot is applied by the state or the opposition it is with the intent of weaponizing the derogatory connotations, which links back to ideas of incivility, and pointless danger and violence. Through this, there is a continuation and upholding of colonial violence.

Conversely, protest is seen as an explicitly peaceful event, intending to inspire change and raise awareness. The use of protest has come to be linked to liberalism, especially in cases when the protest is a registered event with the governing body. We also believe it’s important to include definitions from an organizing lens, to inform why the actors, the people, might use these words. Protest is understood as a tactic which can be part of a strategy of applying pressure to those in power, redirecting focus to the issue at hand, and as a display of collective power. Protest is an umbrella term encompassing rallies and marches, as well as more escalated actions such as building occupations and art installations. On the other hand, riots are seen as chaotic and unstrategic because they are difficult to manage. A riot might take place when plans change quickly and communication fails, or the police begin to physically escalate.

Who Gets to Apply the Label?

When it comes to who gets to apply the label of riot, it is most often the media and politicians that are the first to represent a protest as a riot. This representation in turn influences how individuals label the event for themself, but politicians and popular media don’t always give the most contextualized depictions of protests. In recent memory, the representation of riots in America can be said to divide along party lines, with more left-leaning news agencies giving leniency to protesters and more right-leaning media promoting messages of law and order. Still, there is a deeper problem within American media that decontextualizes political events. This comes from a lack of a deeper psychological and historical context of the so-called violence that can occur.

“It [the colonial power] is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield with greater violence.”

Frantz fanon [8]

The needed context for understanding a protest can be as simple as the inclusion of all the factors that led to escalation of the “riot” such as unaddressed systemic issues or police response. In addition, media across the political aisle must do better to further contextualize violent uprisings as a reaction to colonial oppression, for example how Frantz Fanon offers the opinion on “violence” as a necessary method of resistance [9]. Fanon’s chapter of Wretched of the Earth called “Concerning Violence” explores how the idea of violence can often be understood within the context of colonization. Now, we are not suggesting that Fox News should be expected to accurately portray Fanon’s ideas, nor would that be realistic, but all media can do a better job showing how colonial violence will always be a much greater evil than property damage or perceived violence from civil unrest.

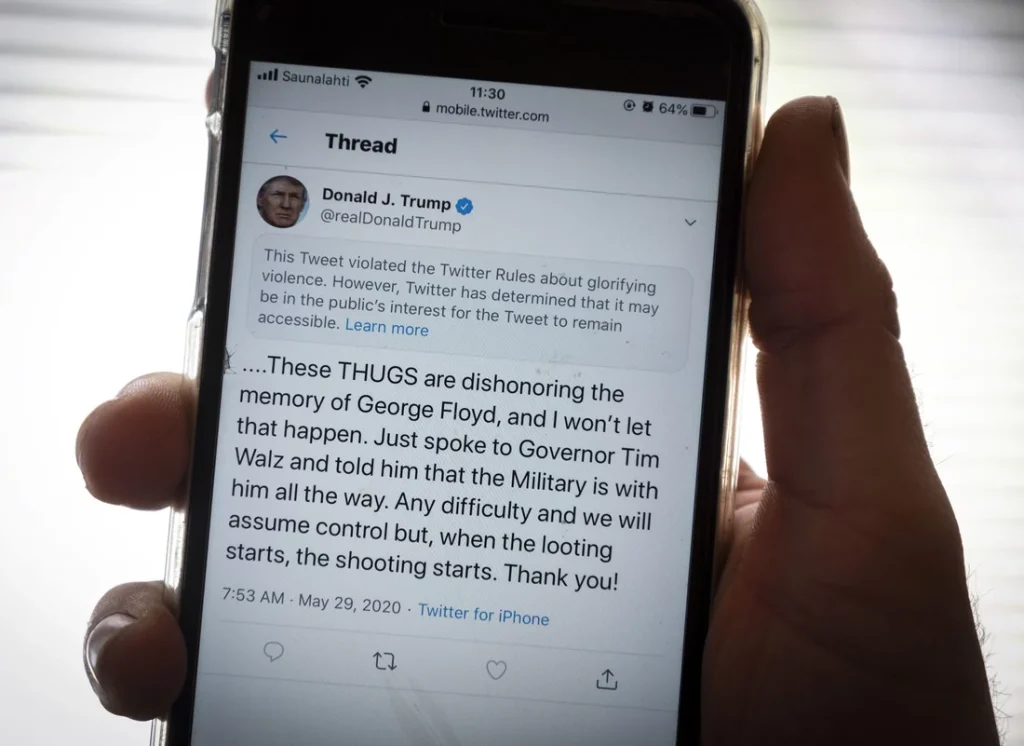

In the same way that media representations can be skewed by political affiliation, politicians will often use protests as an opportunity to make statements of endorsement of disapproval. Look no further than sitting president Donald Trump applying labels like “rioters, looters, and thugs” to the protesters in the summer of 2020. Even though the context of those so-called riots were the murder of a black man named George Floyd by police and a history of racism and slavery ingrained in the country’s past, this was overlooked. Instead, politicians from across the aisle were using Floyd’s death as a cause to bolster their careers.

Sprunt, Barbara. “The History Behind ‘When The Looting Starts, The Shooting Starts.’” NPR, May 29, 2020.

1968 Chicago Riots

Unrest in America was reaching a boiling point in 1968. The Vietnam War was killing record numbers of American troops, Red and Black Power movements for social justice, and on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by a white man in Memphis. The protests that ensued across dozens of cities in the country, including Chicago, escalated quickly and were deemed as violent riots. On April 15, Mayor Daley of Chicago “ordered officers to ‘shoot-to-kill’ arsonists and ‘shoot-to-maim’ looters in the event of any future disturbance” [10].

Chicago History Museum. “Chicago 1968: Law and Disorder,” June 23, 2014.

Like any riot or moment of collective distress, many people had different reactions to the disturbances that took place after the death of MLK. In the book of poetry titled “Riot” by Gwendolyn Brooks, the reader is offered three perspectives of the “riots” in Chicago through three different poems. Brooks portrays the feelings of both the oppressor and the oppressed in the racialized context of rioting. In the first poem, readers see the perspective of a wealthy white man named John Cabot who is watching a riot unfold. He stands to represent the ignorance of those who oppose the rioters, exposing the detachment of the privileged from those who are resisting oppression. In the second poem, Brooks delves into the systemic violence and historical oppression that can cause riots, while maintaining hope through themes of survival and resistance. While riots can be defined by violence and destruction, Brooks also offers space to explore the communal grief, understanding, and love that can be present at the same time. On the final page of the book, a sort of historical context is given for the poem “Riot” below a picture of Gwendolyn Brooks. The one sentence synopsis says that the poem “arises from the disturbances in Chicago after the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968.” There was a very conscious decision to call the unrest that occurred in Chicago “disturbances” instead of “riots”—perhaps playful irony, or entirely serious. This is contrasted with the opening quote on the first page of the book from Henry Miller in 1944 that reads, “It would be a terrible thing for Chicago if this black fountain of life should suddenly erupt…Maybe the Negro will always be our friend, no matter what we do to him.” From the first page to the last there is a contrived array of differing perspectives of what a riot is, with Brooks’ poems fitting comfortably between them [11].

1992 Los Angeles Riots

Turnley, Peter. Rodney King Riots, South Central LA. 1992. Archival pigment print, 13 1/4 x 20. Lehigh University Art Galleries, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA.

In 1991, the violent beating of Rodney King, an unarmed African American man detained for speeding, ignited widespread protests against police brutality and systemic racism. Tensions escalated further when Soon Ja Du, a Korean-American store owner, shot and killed Black teenager Latasha Harlins over allegations of shoplifting. In April 1992, following the acquittal of the officers involved in the Rodney King case, protests erupted across Los Angeles, resulting in 63 fatalities, 2,383 injuries, the destruction of 2,000 businesses, and more than $1 billion in property damage. This period marked one of the most devastating instances of civil unrest in U.S. history since the Watts riots of the 1960s [12].

The story quickly garnered national and global attention, with media outlets eager to cover the looting and fires. The role of the media in shaping public perception was significant; mainstream coverage amplified the situation by emphasizing the racial tensions between Korean and Black Americans, portraying the riots as an attack from one racial group against another. For the first 48 hours of the events, all seven of L.A.’s news stations broadcasted near constant coverage of violence and destruction. What was often overlooked in this coverage were the background issues that gave cause to the violent reaction, namely the severe inequalities and economic challenges faced by both communities [13]. Applying our knowledge that riots, no matter how destructive and “out-of-control” they may seem, are moments where groups contend with their lack of improvement within a discriminatory system, the 1992 L.A. riots are more straightforward to decipher. In the 1980s and ’90s, many Koreans had immigrated to the Los Angeles area. Because of low rents, they opened groceries, liquor stores, and other businesses in South Central—a predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhood. The existing community there faced multiple obstacles, including high unemployment brought on by factory closures and being denied bank loans to start their own businesses. Then, due to cultural differences and a lack of historical knowledge/appreciation of past African American civil rights struggles by newly immigrated Koreans to the United States, resentment and fear began to grow [14]. Because the media glossed over these background factors, public discourse around the riots centered around lawlessness and violence and left little space for mentioning the legitimate frustrations over police brutality, racism, and economic inequality that fueled the unrest in the first place.

Concluding Thoughts

However exhaustive our proposed digital repository of the term “riot” may be, it is our position that riots cannot entirely be defined. As we have analyzed in this collection of multimedia sources and works, any definitions of “riot” are informed by differing interpretations of history and the racialization of perceived violence. Instead of giving a concrete definition, it is our hope that viewers will explore the different perspectives and contexts that the term riot can entail. While it is a label thrown around often without nuance, we are hopeful that people will come to contextualize riots as products of complicated history within larger systems of colonial violence.

Contributors

Anya Kalucki, Rishika Vaid, Loey Waterman, and Sal Ryan

References

- “Riot.” Merriam-Webster, 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/riot.

- U.S. House of Representatives. 2024. “Title 18, Chapter 102.” United States Code. Accessed October 8, 2024. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title18/part1/chapter102&edition=prelim.

- Newburn, Tim. “The Causes and Consequences of Urban Riot and Unrest.” Annual Review of Criminology 4, no. 1 (January 13, 2021): 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-061020-124931.

- King, Martin Luther Jr., “The Other America” (speech, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, April 14, 1967).

- Moynihan, Daniel P. 1965. The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. Office of Policy Planning and Research, U.S. Department of Labor Washington, DC.

- Hrach, Thomas J. The Riot Report and the News: How the Kerner Commission Changed Media Coverage of Black America. University of Massachusetts Press, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1hd19kh.

- Anderson .Paak. “Lockdown”. Aftermath Entertainment, 2020. Youtube Video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TgItkJCm09c

- Fanon, Frantz. “Concerning Violence.” In The Wretched of the Earth, 61. 1961. Reprint, Grove Press, 2021. https://pages.ucsd.edu/~rfrank/class_web/ES-200A/Week%203/FanonWotEviolence.pdf.

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 35–106.

- Chicago History Museum, “Chicago 1968: Law and Disorder,” 2014.

- Brooks, Gwendolyn. Riot. Detroit, Michigan: Broadside Press, 1968. https://eclipsearchive.org/projects/RIOT/Riot.pdf.

- Ligon, Tina. “Frustration & Fire: The 1992 Los Angeles Uprising.” Rediscovering Black History (blog), April 29, 2022. https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2022/04/29/frustration-fire-the-1992-los-angeles-uprising/.

- Smith, Erna. “Transmitting Race: The Los Angeles Riot in Television News.” Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series, May 1994. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/r11_smith.pdf.

- The Asian American Education Project. “The 1992 L.A. Civil Unrest, Systemic Racism.” Lesson Plans and Educational Resources. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://asianamericanedu.org/1992-la-civil-unrest-systemic-racism.html.

Bibliography

American Experience | PBS. “The Anatomy of Unrest | What the History?!” YouTube, May 22, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rmx8ilJdr4Q.

Anderson .Paak. “Lockdown”. Aftermath Entertainment, 2020. Youtube Video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TgItkJCm09c.

Brooks, Gwendolyn. Riot. Detroit, Michigan: Broadside Press, 1968. https://eclipsearchive.org/projects/RIOT/Riot.pdf.

Chicago History Museum. “Chicago 1968: Law and Disorder,” June 23, 2014. https://www.chicagohistory.org/exhibition/chicago-law-and-disorder/.

Fanon, Frantz. “Concerning Violence.” In The Wretched of the Earth, 35–106. 1961. Reprint, Grove Press, 2021. https://pages.ucsd.edu/~rfrank/class_web/ES-200A/Week%203/FanonWotEviolence.pdf.

Gonzalez, Carlos. BLM 2020 Minneapolis Riot Image. Star Tribune. Getty Images, June 2020. https://www.city-journal.org/article/will-it-be-riot-season-again-in-2024.

Hrach, Thomas J. The Riot Report and the News: How the Kerner Commission Changed Media Coverage of Black America. University of Massachusetts Press, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1hd19kh.

King, Martin Luther Jr. “The Other America” (speech, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, April 14, 1967).

Ligon, Tina. “Frustration & Fire: The 1992 Los Angeles Uprising.” Rediscovering Black History (blog), April 29, 2022. https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2022/04/29/frustration-fire-the-1992-los-angeles-uprising/.

Merriam-Webster. “Riot.” Merriam-Webster, 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/riot.

Moynihan, Daniel P. The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. Office of Policy Planning and Research, U.S. Department of Labor Washington, DC, 1965.

Newburn, Tim. “The Causes and Consequences of Urban Riot and Unrest.” Annual Review of Criminology 4, no. 1 (January 13, 2021): 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-061020-124931.

Paak, Anderson. “Anderson .Paak – Lockdown.” YouTube, June 19, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TgItkJCm09c.

Smith, Erna. “Transmitting Race: The Los Angeles Riot in Television News.” Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series, May 1994. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/r11_smith.pdf.

Sprunt, Barbara. “The History Behind ‘When The Looting Starts, The Shooting Starts.’” NPR, May 29, 2020, sec. Politics. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/29/864818368/the-history-behind-when-the-looting-starts-the-shooting-starts.

The Asian American Education Project. “The 1992 L.A. Civil Unrest, Systemic Racism.” Lesson Plans and Educational Resources. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://asianamericanedu.org/1992-la-civil-unrest-systemic-racism.html.

Turnley, Peter. Rodney King Riots, South Central LA. 1992. Archival pigment print, 13 1/4 x 20. Lehigh University Art Galleries, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24691871.

U.S. House of Representatives. 2024. “Title 18, Chapter 102.” United States Code. Accessed October 8, 2024. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title18/part1/chapter102&edition=prelim.