Diaspora

Definition

As is the case for many keyword terms within Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora Studies, there are many differing opinions on what the exact definition of diaspora is. The term comes from the Greek root –sperein, which means “to sow,” and the prefix dia-, which refers to movement through something. [1]

These sentiments of movement and of sowing seeds are reflected in several highly influential explorations of the term diaspora, such as in famed political scientist and seminal thinker of modern diaspora studies William Safran’s article “Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return” for the first ever issue of “Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies.” Throughout his article, Safran provides a kind of list of what he considers to be the defining characteristics of diaspora, writing that a diaspora can be defined as an “expatriate minority community” whose members share more than one of the following characteristics: 1) they have been dispersed to 2 or more locations that are peripheral to the homeland, 2) they share some sort of collective mythology about the homeland from which they were dispersed, 3) they believe that acceptance by and assimilation into their hostland is not possible, and experience a feeling of alienation from the host society as a result of this, 4) they think of their homeland as as their “true, ideal home,” and hope to–or believe they should–return there eventually, 5) they believe their community should be collectively concerned with the wellbeing of their homeland and working towards its bettering, and 6) they continue to relate in some deep or otherwise personal way to their homeland, and find identity and community in this relationship. [3] Though this definition does not shed light on the distinction between voluntary and forced or coerced migration of diasporic groups, it is still helpful in our general framing and understanding of the term, especially if we analyze individual diasporas with this critical eye and differentiation.

Diaspora is more simply defined by many as a “scattered population whose origin lies in separate geographic locations”. It refers to community of people who do not live in their country of origin but maintain the culture and heritage of their homeland. It may include the dispersal of people for a variety of reasons, such as “expulsion, expansion, commercial endeavors, or pursuit of employment”. [4] Although the definitions may very from source to source, all definitions recognize that the dispersed community is committed to practicing and restoring homeland values, while simultaneously adapting them to their new environments.

Discussion

Jewish Diaspora

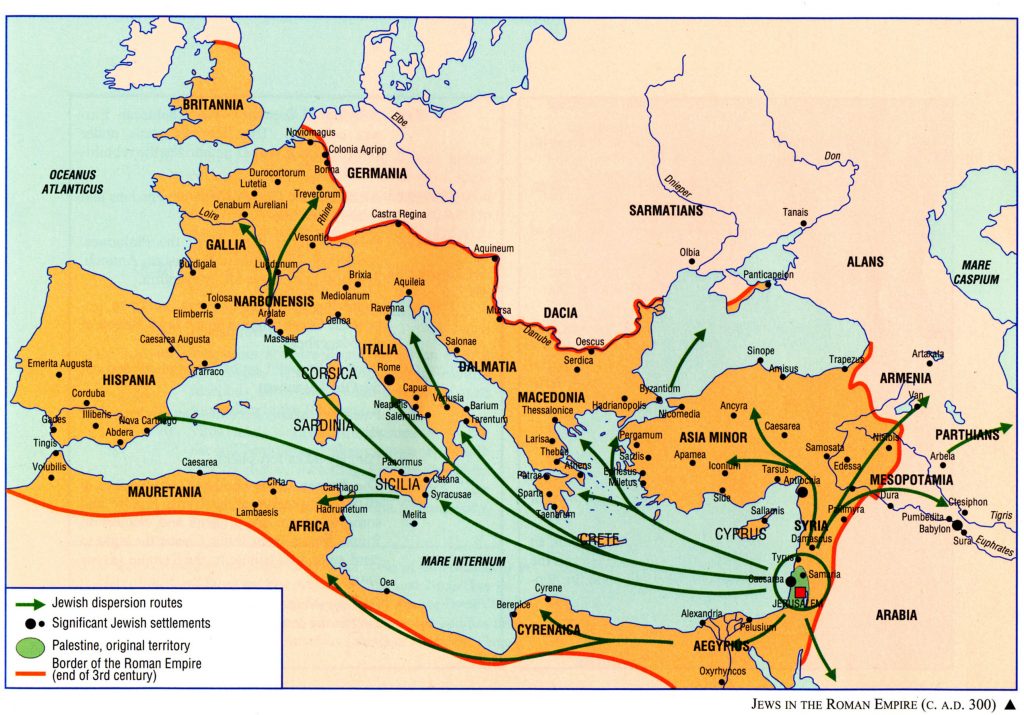

In understanding the term diaspora, it is important to first return to its genesis and initial use in order to better understand how and why this term first came to be. One of the first recorded uses of the term diaspora was in the Septuagint—the oldest surviving Greek translation of the Torah, the Hebrew Bible, initially created for Egyptian rulers by a select group of Jewish scholars—in roughly 250 BCE. [6] This particular use of the term diaspora was meant to refer to the forced exile of the Jews from what they considered to be their historic homeland, as well as the subsequent global dispersion of Jewish populations and the obstacles and oppressions that came with that dispersal. Since the twentieth century the Jewish diaspora has also referred to the dispersion of Jews from European countries as a result of the Holocaust and the systemic segregation and extermination of Jewish peoples within these countries.

For many years since the coining of the term, as William Safran explains in his seminal article “Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return,” published in 1991, diasporas received little attention from both academic and popular communities. When the term was used, Safran explains, it was used almost exclusively to describe the experience of the initial exile of the Jews, which made it significantly less helpful and common in conversations about other categories of people—in the cases of the Armenian or Polish diasporas, the framework of the Jewish diaspora works relatively well, but in analyzing groups such as the Palestinian diaspora or the African diaspora, the Jewish example works less cleanly. [7] In his article “The ‘diaspora’ diaspora,” Rogers Brubaker explains how the majority of early discussions on the topic of diaspora were primarily concerned with the concept of a “homeland,” again drawing from the case of the Jewish diaspora. Brubaker writes that “some dictionary definitions of diaspora, until recently, did not simply illustrate but defined the word with reference to that case.” [8] Though the definition of diaspora is generally understood to be far more nuanced today, many definitions of diaspora—particularly earlier definitions of diaspora—define themselves with reference to the diaspora of the Jewish people rather than simply using this diaspora as an illustrative example. In more contemporary definitions of the term or in modern manifestations and understandings of existing diaspora(s), it is vitally important to keep this history in mind.

As our understanding of the term diaspora has adapted over time, we have gained a deeper and more nuanced understanding how other diasporas came to be, such as the African diaspora.

African Diaspora

The African diaspora is the dispersal of Africans outside of Africa. This movement of people dates back to the Atlantic slave trade which is the first occurrence of disorientation for a group of people to this extent. The term diaspora in this situation refers to the involuntary movement of people to the Americas and Europe. The development of the African diaspora was significant to the beginning of European expansion and capitalism. By stealing and enslaving Africans from their homeland, and forcing them to become racialized labor workers during the era of colonization and development of America, European colonization was able to thrive. The formation of this diaspora echoes the overarching definition of diaspora; the African population in the Americas were bonded with one another through their shared experiences and dispossession to their home in Africa. Not only were they connected by their culture, trauma, and values, but also by their shared position of power in their new society. For the most part, African slaves maintained there a connection to their hometown especially due to the arrival of more African-born slaves. Over time, the idea of black-identity has changed and been molded by history, racism, and racial politics. The slave trade and the African diaspora have had massive impacts on the economic, social, political, and cultural sectors of past and present events and experiences.

Although the African diaspora began with the involuntary movement, the New African diaspora is the dispersal of Africans voluntarily. The current migration outside of Africa raises questions on the identity politics that surround the terms African-American and black. The New African diaspora in the USA is associated with African immigrants redefining racial affiliation in America in which their American-born counterparts have a different relationship. This makes it difficult to organize a unified black platform of African-American social and political relationships (“The New African Diaspora”). New waves of migration, therefore, play a key role in evolving ideas of both African diasporas, and the concepts of diaspora in general.

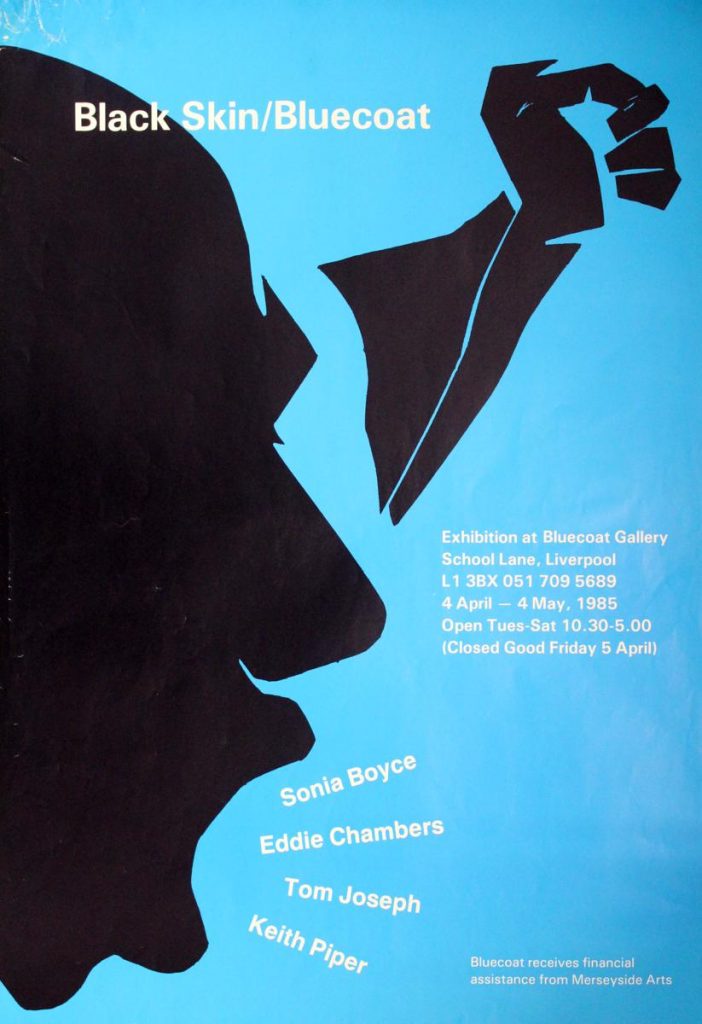

Black Skin/Bluecoat is a visual art exhibition at Bluecoat gallery that focuses on the representation of black voices and the African diaspora in art and society.

Post-Modernist Constructions of Diaspora

The growth of capitalism and globalization, especially after World War II, became a turning point for ideas of diaspora, especially as migration flows and nation-states and state identities were greatly changed. As globalization persisted throughout the twentieth century, postmodern views of diaspora became more widely discussed and popular. For periods of time, diasporic communities were once solely framed as victims, forced to leave their homelands, with some “origin-states” also regarding diasporic community members as traitors and deserters [11]. However, acknowledgments from academic communities of the hybridization and creolization occurring within transnational communities have also emphasized the loss of territorial connection of diaspora communities. No longer are diasporic communities victims who long for a homeland in the form of a nation-state. Instead, the idea of diasporas experiencing hybridization has come to represent cultural identities within tradition, that draw from the old and the new without total assimilation and loss of the past. Musical genres, linguistic patterns, religious practices, and aesthetic styles are more creolized and globalized than ever before. This is especially the case with diasporic youth who are often raised with the influences of more than one cultural heritage and begin to be able to choose how they express themselves culturally [12]. Diasporas, at this point in history, can never solely be nationalist and about the creation of the nation-state. While members of diasporas still long for homeland through the nation-state, for example, Zionists, many do not have longings or nostalgia for a physical state, but something beyond the physical, and perhaps, the spiritual.

Diaspora in the Age of Globalization

As of 2012, diasporic ministry offices exist in 40% of United Nations member-states. Many emigrants and their descendants often are given extra-territorial citizenship privileges and are encouraged to send financial remittances and make investments in their homeland country, further complicating the physical bounds of nation-states and creating transnational identities that have significance in the transnational field [13]. Moreover, in the field of ethnic and cultural studies in the United States, diaspora is also discussed as something beyond the nation-state and territorial ties. Asian-American studies scholar Schlund-Vials, in particular, highlights how the concept of diaspora, and diasporic identity conflict with inflexible and settled definitions of identity, confined by nation and borders. In their definition, diaspora contrasts with a fixed “singlenation identification.” Schlund-Vials emphasizes the fluidity of diasporic identity, emphasizing how key mobility is in its creation [14]. Meanwhile, scholarship in Chicanx studies and Africana studies within the United States also discussed the fluidity and non-physicality of nations and borders. One pertinent example includes Chicana Feminist Gloria Anzaldua’s influential 1987 book Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza.

Home(1999) by Mona Hatoum

Hatoum is a Palestinian artist who moved to Britain from Lebanon as a young adult when the Lebanese civil war broke out. She often makes art that displays themes of displacement, war, conflict, and identity transformation. Home (1999) depicts a domestic kitchen scene. An electric current passes through wires on the counter in between each of the household kitchen objects. The sounds of electricity give everyday objects, which usually carry themes of safety and warmth, a much more menacing and uncertain feeling.

Since the initial rise of cultural studies in academia, the term diaspora has grown in its possible definitions and uses. Many of these modern uses of the definition are helpful in updating the term to fit a rapidly-changing contemporary world. However, without clear boundaries described in its definition, many of the newly crafted uses of the word may stray too far from the original application of the term and begin to benefit populations who are migrating freely. Using the word in this manner may eliminate the purpose it has to call attention to the displacement of people and the ways in which displacement, violence, and dispersal can affect community and identity. For example, in modern days, the term is often used when referring to the refugee crisis and the many civil wars of today and the past few decades, such as the Syrian diaspora, the Venezuelan diaspora, and the Afghan diaspora. In the broadcasting of the Russo-Ukrainian War, there has been a discussion of a Ukrainian diaspora. In order to give these communities the diasporic spaces they may need, discussion of the term’s uses is essential.

Additionally, with the rise of the internet in the past few decades, members of diasporas formed from recent civil wars, and even diasporas developed hundreds of years ago, are able to communicate much more easily. It is much easier to find someone who has shared a similar experience with the reach of the Internet (broadening the terms of diaspora even wider due to the ability to create unity with members further away than before).[15] Technology, as a method of increasing collective unity, can be extremely useful in combatting issues such as literacy(digital and financial literacy as well) and racism in the areas of dispersal. This modern tool can have effects ranging from members of the Afghan-Dutch diaspora spreading helpful information about the COVID-19 virus with healthcare professionals in Afghanistan using online platforms to the creation of an online platform that provides tools such as English and financial literacy courses (along with information about public health and legal counseling opportunities) to Mexican asylum seekers. Another brilliant tool created by a community of Colombian diaspora members using the powers of technology is INTIMAL; an art-research project dedicated to providing a space to share experiences about migration and dispersal. Initially, it began as an online platform where women of the Colombian diaspora shared drawings, stories, and even medicinal recipes relating to their migratory experiences. Today, INTIMAL exists as an app that is used to connect members of multiple diasporas to share feelings of geographical and cultural loss with the motivation to facilitate healing and a sense of place and presence.[16]

As more and more countries are being impacted by exodus and war, where does one draw the line between the creation of a diaspora and transnational migration? Can and should nations who are responsible for the forced displacement of people through colonialism and imperialism, centuries ago or today, benefit from the term diaspora and the sense of unity it can provide?[12] These are important topics to discuss as the world changes and nations that were once perpetrators of exodus through imperialism have changed roles in global relations.

Fiddler on the Roof (1971) directed by Norman Jewison.

This film is an Oscar-winning adaptation of the infamous Broadway Musical about the life of a Jewish community in pre-revolutionary Russia.

The film depicts the struggles and hardships of the Jewish diaspora in Russia and educates the audience on Jewish identity, customs, and relationships through the focus on a poor milkman and his five daughters.

Additional Resources

that focuses on the refugee crisis and the mass migration of humans today. The film contains many first-person accounts of refugees and volunteers discussing their experiences.

Footnotes

- Jane Evans and Anita Mannur, “Diaspora,” ed. Lisa Disch and Mary Hawkesworth, The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, July 9, 2015, pp. 164-178, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.9.

- Stefan Zechner, “MAPPED: The Top Immigrant Population in Each Country,” Western Union, October 2, 2017. https://www.westernunion.com/blog/en/world-immigration-map/.

- William Safran, “Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1, no. 1 (1991): 83–99, https://doi.org/10.1353/dsp.1991.0004.

- André Gabrielli, “Definitions in the Field: Diaspora,” National Geographic Society, September 27, 2022, https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/definitions-field-diaspora.

- Gerard Chaliand and Jean-Pierre Rageau, Jews in the Roman Empire (c. A.D. 300), Mapping Globalization, Accessed December 1, 2022, https://commons.princeton.edu/mg/jews-in-the-roman-empire-c-a-d-300/.

- Jane Evans and Anita Mannur, “Diaspora,” ed. Lisa Disch and Mary Hawkesworth, The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, July 9, 2015, pp. 164-178, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.9.

- William Safran. “Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1991, pp. 83–99, https://doi.org/10.1353/dsp.1991.0004.

- Rogers Brubaker, “The ‘Diaspora’ Diaspora,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28, no. 1 (August 18, 2006): 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000289997.

- Archie Rand, “The 19 Diaspora Paintings,” BOMB Magazine, July 1, 2003, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/the-19-diaspora-paintings/.

- Andoni Alonso and Pedro J. Oiarzabal, Diasporas in the New Media Age: Identity, Politics, and Community, Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2010.

- Cohen Robin. Global Diasporas : An Introduction. UCL Press 1997.

- ibid

- Gamlen, Alan, ‘The Global Rise of Diaspora Institutions’, Human Geopolitics: States, Emigrants, and the Rise of Diaspora Institutions (Oxford, 2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 20 June 2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198833499.003.0002, accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

- Schlund-Vials, Cathy J., et al. Keywords for Asian American Studies. Edited by Cathy J. Schlund-Vials et al., New York University Press, 2015.

- Tobias Wofford, “Whose Diaspora?,” Art Journal 75, no. 1 (2016): 74–79, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43967654.

- Magda Rodríguez Dehli and Larisa Lara Guerrero, “Idiaspora – Connect, Learn, Contribute,” Empowering Global Diasporas in the Digital Era, 2021, https://www.idiaspora.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl181/files/resources/document/routedidiaspora2021empowering-global-diasporas-in-the-digital-era.pdf.

References

Alonso, Andoni, and Pedro J. Oiarzabal. Diasporas in the New Media Age: Identity, Politics, and Community. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2010.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “diaspora.” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 8, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/diaspora-social-science.

Braziel, Jane Evans, and Anita Mannur. “Diaspora.” The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, edited by Lisa Disch and Mary Hawkesworth, 9 July 2015, pp. 164–178., https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.9.

Brubaker, Rogers. “The ‘Diaspora’ Diaspora.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28, no. 1 (August 18, 2006): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000289997.

Butler, Kim D. “Defining Diaspora, Refining a Discourse.” Diaspora 10.2, 2002.

Chaliand, Gerard, and Jean-Pierre Rageau. Jews in the Roman Empire (c. A.D. 300). Mapping Globalization. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://commons.princeton.edu/mg/jews-in-the-roman-empire-c-a-d-300/.

Cohen Robin. Global Diasporas : An Introduction. UCL Press 1997.

Evans, Jane, and Anita Mannur. “Diaspora.” The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, edited by Lisa Disch and Mary Hawkesworth, 9 July 2015, pp. 164–178., https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.9.

Gabrielli, André. “Definitions in the Field: Diaspora.” National Geographic Society, September 27, 2022. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/definitions-field-diaspora.

Gamlen, Alan, ‘The Global Rise of Diaspora Institutions’, Human Geopolitics: States, Emigrants, and the Rise of Diaspora Institutions (Oxford, 2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 20 June 2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198833499.003.0002, accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

Hatoum, Mona. “Home.” Art Installation, 1999. Tate Modern. London, England.

“Introduction to the African Diaspora across the World.” Institute for Cultural Diplomacy, www.culturaldiplomacy.org/index.php?en_programs_diaspora.

Rand, Archie. “The 19 Diaspora Paintings.” BOMB Magazine, July 1, 2003. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/the-19-diaspora-paintings/.

Rodríguez Dehli, Magda and Larisa Lara Guerrero. “Idiaspora – Connect, Learn, Contribute.” Empowering Global Diasporas in the Digital Era, 2021. https://www.idiaspora.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl181/files/resources/document/routedidiaspora2021empowering-global-diasporas-in-the-digital-era.pdf.

Safran, William. “Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return.” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1, no. 1 (1991): 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1353/dsp.1991.0004.

Schlund-Vials, Cathy J., et al. Keywords for Asian American Studies. Edited by Cathy J. Schlund-Vials et al., New York University Press, 2015.

“The New African Diaspora.” Google Books, Google, www.google.com/books/edition/The_New_African_Diaspora/CMg–t-YQWQC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA3&printsec=frontcover.

“The Transatlantic Slave Trade and Origins of the African Diaspora in Texas.” Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture, 15 Dec. 2019, www.pvamu.edu/tiphc/research-projects/the-diaspora-coming-to-texas/the-transatlantic-slave-trade-and-origins-of-the-african-diaspora-in-texas/.

Wofford, Tobias. “Whose Diaspora?” Art Journal 75, no. 1 (2016): 74–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43967654.

Zechner, Stefan. “MAPPED: The Top Immigrant Population in Each Country.” Western Union, October 2, 2017.

Contributors

Victoria Muller-Kahle

Liani Astacio

Naomi Roberts

Shaiya Sayani