Intersectionality

Definition

Many keywords within the studies of race, colonialism, and diaspora cannot really be traced to having one creator with a specific goal. “Intersectionality” is different; it is a term that one person, Kimberlé Crenshaw, specifically created to address a lack of understanding of Black women’s experiences (which is discussed in more detail below). Given that Crenshaw is the clear creator of this word, and given that she coined it in no small part based on her own experiences, her definition should probably be given more weight than other definitions when considering the different meanings of intersectionality. At the same time, the meaning of a term can gain depth and nuance over time if others add their own views and experiences onto it, and so it is important to consider others’ definitions and understandings of intersectionality as well.

If we were to create a definition for intersectionality that incorporates both Crenshaw’s ideas and the ideas of others, it would roughly look like this: Intersectionality is a framework of thinking used to understand and dismantle interlocking systems of power that create inequality based on how perceived identities converge, fostering unique life experiences of both privilege and oppression. Intersectionality includes identities that are concurrent, not separate from, one another. Intersectionality can be considered a “concept,” and it can be used as a “tool.”

Discussion

Civil rights activist, scholar, and professor Kimberlé Crenshaw first coined the term “intersectionality” in a 1989 paper.[2] Twenty years later, she described intersectionality as being “a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things.”[3] In her original paper, Crenshaw went into much more detail about intersectionality. In essence, she created the term as a response to a lack of understanding the marginalization and oppression that Black women face—not what they face as a Black person, or as a woman, but as a combination of both—and how this lack of understanding leads to Black women sometimes being excluded from feminist and antiracist ideals. She explains how “in race discrimination cases, discrimination tends to be viewed in terms of sex- or class-privileged Blacks; in sex discrimination cases, the focus is on race- and class-privileged women. This focus on the most privileged group members marginalizes those who are multiply-burdened and obscures claims that cannot be understood as resulting from discrete sources of discrimination.”

“Naturally” by Audre Lorde, from The Black Woman: An Anthology, compiled by Toni Cade Bambara. This anthology contains essays, short stories, poetry, and other works by notable Black women in the United States.[4]

To Crenshaw, understanding the idea of intersectionality also means accepting the need for a new framework that will accurately represent intersectional identities. She says that the current “problems of exclusion cannot be solved simply by including Black women within an already established analytical structure… For feminist theory and antiracist policy discourse to embrace the experiences and concerns of Black women, the entire framework that has been used as a basis for translating ‘women’s experience’ or ‘the Black experience’ into concrete policy demands must be rethought and recast.”[2]

Crenshaw also discusses intersectionality in the TED Talk above, entitled “The Urgency of Intersectionality.” She begins her talk by asking the audience to identify the names of black people killed by police within the last two years. The audience members sat when they heard an unfamiliar name. It was no surprise to Crenshaw that more people sat down when she listed the names of black women. Crenshaw had conducted this experiment numerous times and found that “the awareness of the level of police violence that black women experience is exceedingly low.” The issue here is that because there is no framework of thinking about how police brutality affects black women, people cannot imagine or understand the problem. Crenshaw gives the audience another example of Emma DeGraffenreid, an African-American woman who claimed race and gender discrimination against an employer. The judge who handled this case dismissed the suit because the employer had a history of hiring women and African-Americans. Although this was true, what was not considered is that the women hired were mostly white women, and the African-Americans hired were mostly men. What the judge and many people fail to do is take this intersectional framework of thinking about problems like Emma’s and the countless other people marginalized by their identities. Intersectionality is a necessary framework for solving this problem because, as Crenshaw states, “Where there’s no name for a problem, you can’t see a problem, and when you can’t see a problem, you pretty much can’t solve it.” People need to use intersectionality as a tool to understand how people can experience the simultaneous impacts of racism and sexism–or ableism, xenophobia, homophobia, or Islamophobia, to name just some. Once people take in this understanding of intersectionality as this framework of thinking about these imbalanced power dynamics and oppressive systems, then they can use it as a tool to fix such injustices. Although Crenshaw’s ideas and views are important, her definition is slightly ambiguous. It is therefore important to examine other scholarly definitions of intersectionality to have a well-rounded understanding of the concept.

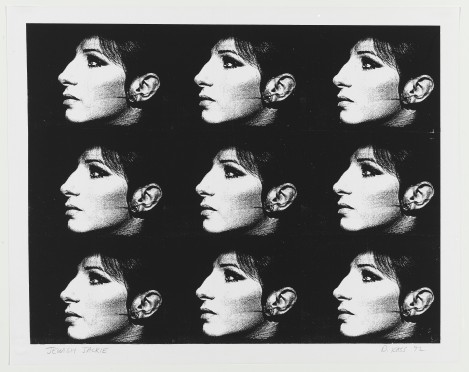

“Jewish Jackie” by Deborah Kass. “Jewish Jackie” is a take on Andy Warhol’s famous “Jackie II” which portrayed Jackie Kennedy. In this piece, Kass replaced Kennedy with Barbara Streisand. Growing up both Jewish and female, Kass did not have much representation in the media. “Jewish Jackie” is a critique of the exclusionary depictions of Jewish women in the media.[6]

The Center for Intersectional Justice (CIJ) is a nonprofit organization based in Berlin that is a leader in the world of intersectional approaches to equity. They work to address intersectionality in systemic oppression across Europe through advocacy, education, and policymaking. The CIJ defines intersectionality as “the ways in which systems of inequality based on gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability, class and other forms of discrimination ‘intersect’ to create unique dynamics and effects.”[7] This definition provides concrete examples of groups who are likely to be oppressed at the crossroads of their various perceived identities. This definition lacks specificity of what intersectionality impacts by only mentioning “unique dynamics and effects.” Other scholarly definitions are more explicit in their descriptions.

A piece from the “Vessels of Genealogies” exhibit by Firelei Báez. Báez’s artwork in this exhibit is meant to portray feminism as well as non-dominant cultures (including through hair and tattoos).[8]

In “Using Intersectionality to Understand Structural Inequality in Scotland: Evidence Synthesis,” a publication funded by the Scottish Government, intersectionality is defined similarly to the definitions of the CIJ and Crenshaw: “a tool for understanding invisible power relations and how they shape inequality, not identity. Intersectionality looks at “interlocking” systems of oppression and how these play out in individuals’ lives.”[9] The study defines intersectionality as a “tool,” meaning it is meant to be used to carry out a particular function, understanding and tackling the invisible power relations which create inequality. In order to address inequality, we must realize its implications on creating the discrimination of such identity. Identity is a major aspect in the definition of intersectionality, and precedes inequality.

A portion of the song “Runnin’” by Tupac Shakur, featuring The Notorious B.I.G., which explores the intersectionality of Blackness and obesity.[10]

In “Using Intersectionality to Understand Structural Inequality in Scotland: Evidence Synthesis,” intersectionality is also defined by what it is not. The publication states that intersectionality is not a synonym for diversity, not about adding up different kinds of inequality, not about pitting different people or groups against each other, nor about constructing a hierarchy of inequality. In saying intersectionality does not mean diversity, the publication asserts that intersectionality should not be confused with identity, like falling under diverse identity groups. For example, if a person is a queer woman, that is not intersectionality. “Intersectionality” in that case would mean the specific ways in which someone who is both queer and a woman is marginalized. Second, intersectionality does not add up a total of identity-based inequalities but rather examines how these inequalities and systems of oppression overlap and work simultaneously against those who are marginalized. Furthermore, intersectionality is not about creating division amongst groups to quantify and evaluate who faces more oppression, nor to value or categorize one form of oppression as more important than another.

Although intersectionality has many benefits, the framework is not infallible. The intersectional perspective is ahistorical. It has no analysis of how the categories themselves were mutually constructed under capitalism, and it views the categories as separate from one another. This is misleading because it highlights the overlap of identity oppression but it ignores the historical context of how all oppression shares roots.

Additional Resources

“Ain’t I a Woman?” is a speech that was delivered by abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth at the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio. Although the term intersectionality was not coined at this time, Truth clearly illustrates the concept in her speech as she describes the unique challenges she faces being both Black and a woman.

“Intersectionality Matters” is a podcast hosted by Kimberlé Crenshaw. Each episode features interviews with famous activists, artists, and scholars, and explores different topics through an intersectional lens. It is available on major podcast platforms, including Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

References

Cited References

1. Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Kimberlé Crenshaw: What Is Intersectionality?” YouTube. YouTube, June 22, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViDtnfQ9FHc.

2. Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum, vol. 1989, no. 1, article 8, pp. 139-167.

3. “Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later.” Columbia Law School, https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later.

4. Lorde, Audre. “Naturally.” African American Registry, February 12, 2018. https://aaregistry.org/poem/naturally-by-audre-lorde/.

5. Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “The Urgency of Intersectionality | Kimberlé Crenshaw.” YouTube. YouTube, December 7, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akOe5-UsQ2o.

6. “Jewish Jackie.” MoMA Learning. MoMA. Accessed December 3, 2022. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/deborah-kass-jewish-jackie-1992/.

7. Center for Intersectional Justice. “What Is Intersectionality?” Center for Intersectional Justice, https://www.intersectionaljustice.org/what-is-intersectionality.

8. “Firelei Báez: Vessels of Genealogies.” DePaul Art Museum. DePaul. Accessed December 3, 2022. https://resources.depaul.edu/art-museum/exhibitions/Pages/baez-vessels-genealogies.aspx.

9. The Scottish Government. “Using Intersectionality to Understand Structural Inequality in Scotland: Evidence Synthesis.” Scottish Government, The Scottish Government, 17 Mar. 2022, https://www.gov.scot/publications/using-intersectionality-understand-structural-inequality-scotland-evidence-synthesis/.

10. Amaru Shakur, Tupac, and Christopher George Latore Wallace. “2Pac (Ft. the Notorious B.I.G.) – Runnin’ (Dying to Live).” Genius, September 30, 2003. https://genius.com/2pac-runnin-dying-to-live-lyrics.

Additional References

Carastathis, Anna. Intersectionality : Origins, Contestations, Horizons. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

Gavieta, Matthew. “The Intersectionality of Blackness and Disability in Hip-Hop: The Societal Impact of Changing Cultural Norms in Music.” International Social Science Review 96, no. 4 (2020): 1–20.

Hancock, Ange-Marie. Intersectionality : an Intellectual History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Hill Collins, Patricia. Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Durham ;: Duke University Press, 2019.

Olsen, Torjer A. “This Word Is (Not?) Very Exciting: Considering Intersectionality in Indigenous Studies.” NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 26, no. 3 (2018): 182–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2018.1493534.

Contributors

Cecilia Bilbe

Claire Robinson

Tsion Tessema