Blood

Definition

The term “Blood” is most commonly perceived as the life-maintaining fluid that flows through the body’s vessels. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary cites blood through a biological lens (fluid that circulates in the heart and veins of a vertebrae animal). Our group has chosen to examine the term “blood” through the lens of colonialism, diaspora, and particularly, through the way blood functions as a “racial arithmetic”, a term coined and defined by Native American scholar Michelle Raheja. We believe that colonialism has conflated ideas of biological blood with socially constructed racialization. Our group has defined “blood” as a tangible way to make social groups, acting as a symbol for racial exclusion and inclusion. This essay will analyze the role blood has played in colonial history and will explore the different ways blood has been racialized and policed for Native Americans, African Americans, and Latinx Americans.

George, Rose. “The Intersection of Race and Blood.” New York Times, May 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/14/well/live/blood-type-race-racial.html?smid=url-share.

Throughout history, blood has been used as a device to separate certain groups of people from the dominant white race. It has also often acted as the sole basis of identity for many, categorizing them and creating significant division within society.

Blood in Native American History:

For Native Americans, blood has had a deep and complex meaning throughout their history and culture. For many tribes, blood acts as a connector between the people and their ancestors, representing the continuity of their cherished traditions and tight-knit community. Indigenous peoples privilege a biological connection to their ancestors, alongside their connection to land [1]. Since these two concepts–ancestry and land–are so vital to the Native culture, it is important to note that their blood and biology is often seen as a means of strengthening these connections.

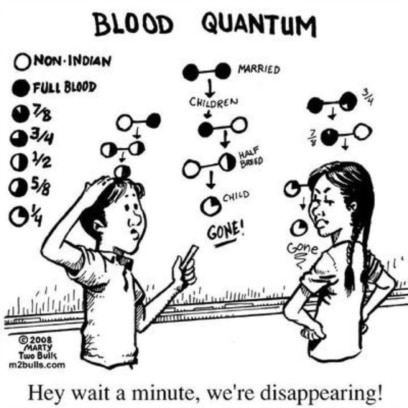

When colonization was at its peak, the significance of blood was altered greatly. After the severe hardships Native Americans faced when settlers arrived, like displacement and a near-extermination of their people, blood symbolized the lasting impacts of these events, including the sacrifices made by their ancestors and the resiliency their people showed. White settlers created the concept of “blood quantum,” a form of quantification for the amount of so-called “Indian blood” an individual possesses [2]. Not only were people categorized and stigmatized based on the amount of blood they had, blood quantum laws were also enacted in the late 1800s. The U.S. government was consistently trying to assimilate the Native people into American society, using these laws as an attempt to erode tribal sovereignty and setting limits on the amount of blood one needed to possess in order to own property. After the Dawes Severalty Act, an act passed that divided Native American tribal lands into individual plots, they used blood quantum as a form of criteria for ownership, deeming that “only those persons with no more than one-half American Indian blood were qualified to own property” [3]. The idea of blood quantum limited Native American freedom greatly, and this was done especially by the American government.

Wilson, Reamus. “Blood Quantum.” Ya-Native Network, www.ya-native.com/pictures/picture_comics/bloodquantum.htm#google_vignette.

Blood quantum, over time, grew into a form of criteria in some Native American communities, with tribes setting different minimums in the amount of blood needed for someone to be able to join, having many negative effects on tribal communities. For one, tribe members have been forced to consider the amount of blood their child would have based on who they choose to have a child with. This limits one’s choice of partner greatly and forces them to alter how they build their families. Additionally, colonization caused a massive strain on reproduction, having many long-lasting effects and further diminishing tribal membership. The pressures on reproduction and conception have hindered Natives’ ability to create families within their own communities. With the impact of urban migration, sexual violence, and inadequate reproductive healthcare, Native tribes have struggled to build families that will fit the blood criteria, leading to a subsequent decrease in membership [4].

Although rules regarding blood quantum in tribal communities have hindered membership, there has been a significant increase in those who identify as Native American due to the increased use of DNA tests in recent years. While this does assist in expanding the number of people in a tribe, it fails to consider how Native culture has or has not played a role in the lives of these people. Allowing DNA profiles to trump other ways of reckoning kin for purposes of enrollment, prioritizes this technoscientific knowledge of certain relations over other, more important types of knowledge, such as cultural connection [5]. Nowadays, the amount of Native blood one possesses appears to be more of a priority rather than an individual’s connection and ancestry when enrolling in a tribe, leading to an even larger loss of cultural identity in Native communities.

“A Conversation With Native Americans on Race,” October 21, 2021. http://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/100000005352074/a-conversation-with-native-americans-on-race.html.

Blood & African American History

The concept of blood in African American history is similar to the history of many other racial groups through its structure of categorizing groups of people, in an attempt to reinforce white settler colonialism. For Black Americans, the historical policing of blood is directly influenced by their role in the formation of the US [6]. In their essay “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor”, Native American scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang asserts the idea that categorizing Black people based on blood is done in an expansive nature that increases the number of Black descendants to ensure that “slave/criminal status will be inherited” [7]. This expansive measurement of blood increased the number of people who would grow up as slaves in America’s “race-specific” chattel slave system [8]. This form of classification also perpetuated the government’s reasoning behind land distribution and in deciding who could claim rightful ownership of land, particularly when that person was Black: “By marking all offspring of white-black couplings as bastards, governments in many jurisdictions prevented these offspring from inheriting the property of a white father” [9].

To further understand why Black Americans are specifically more likely to be considered only Black, even if this is not entirely the case, it is important to understand how hypodescent acts as the law of blood for this particular racial group. The rule of hypodescent is the assignment of “the offspring of mixed races to the subordinate, or “lower status” group” [10]. To focus specifically on how hypodescent controls blood in the Black experience, ethnoracial historian David Hollinger frames hypodescent racialization as a process that occurs when African American identity is viewed through an “either/or” perspective [11]. Black Americans, when mixed with another race, were always viewed and assigned to solely the “Black” race, despite any other components that make up their racial identity. This principle functions as the foundation for blood policing in the African American diaspora and works to uphold standards of white supremacy by making the biological boundary between white people and non-white people very clear.

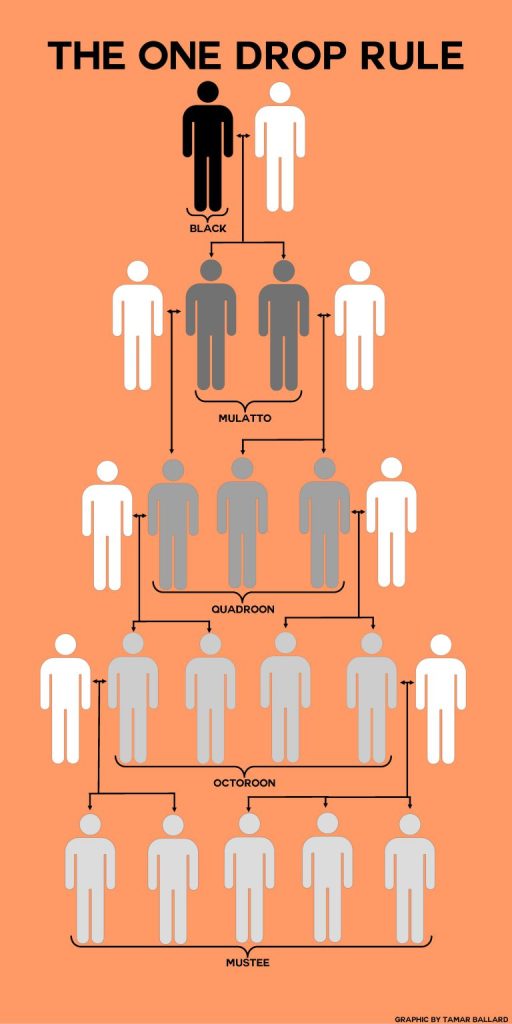

Deriving from the concept of hypodescent was the birth of the one-drop rule. According to historian Patrick Wolfe, this process quantified any amount of African ancestry, “regardless of how remote and of phenotypic appearance” to be a Black person [12]. The one-drop rule persisted through fractional classifications that described people who were half Black as “mulattos”, those who were 1/4th Black as “quadroons”, and those who were 1/8th as “octoroons” [13]. The use of these derogatory terms to refer to Black people based on even a relatively small portion of their ancestral background highlights how closely the concept of blood was monitored and how it shaped racialized social structures.

This diagram shows the fractional classifications that tracked the offspring of white and black couples.

Even among “octoroons, quadroons, and mulattos”, there were “distinctive rights and privileges in some jurisdictions”, which displays how divisive the concept of blood proved to be not only in relation to whiteness, but creating the structure for it to be polarizing within the African American community [14]. The one-drop rule reinforced the barrier between “black and white” and made sure those who identified as Black could not possibly also identify as white.

“It is a fact that, if a person is known to have one percent of African blood in his veins, he ceases to be a white man. The ninety-nine percent of Caucasian blood does not weigh by the side of the one percent of African blood. The white blood counts for nothing. The person is a Negro every time.”

Booker T. Washington

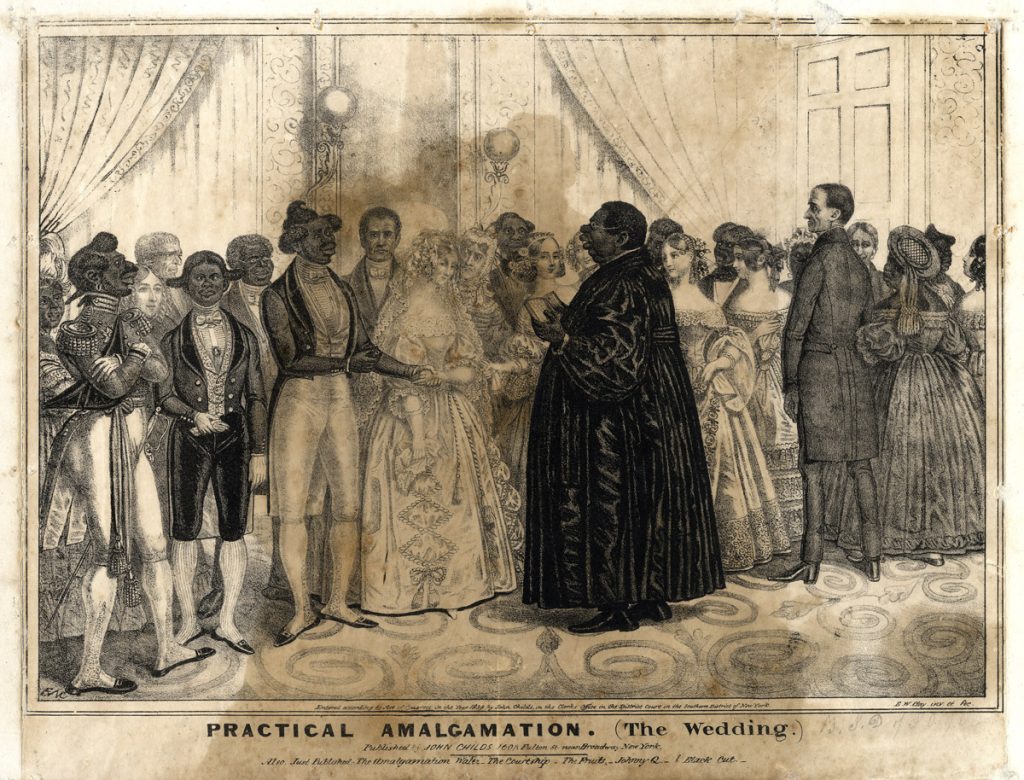

The one-drop rule and the concept of hypodescent are rooted in many anti-miscegenation and admixture laws that can be tracked from the colonial period, all the way to the era of Jim Crow racism. In colonial Jamestown, it was required that any white woman who gave birth to a “mulatto child” pay a fine or face indentured servitude” [15]. Some laws targeted white people involved in interracial mixing, but as the US became more dependent on slavery as a way to drive the nation’s economy forward, the intolerance for interracial mixing can be tracked through state laws that became increasingly targeted towards ensuring Black Americans were more severely punished.

This drawing from E.W Clay portrays caricatures of Black people as buffoonish but depicts the white figures as having more delicate features. Throughout his 1839 series of lithographs, Clay encourages the the physical and social distinctions between White and Black people (framing white people as superior), yet despite their differences, they still sought interracial marriage.

Jessica Viñas-Nelson , “Interracial Marriage in “Post-Racial” America”, Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective

July, 2017

https://origins.osu.edu/article/interracial-marriage-post-racial-america.

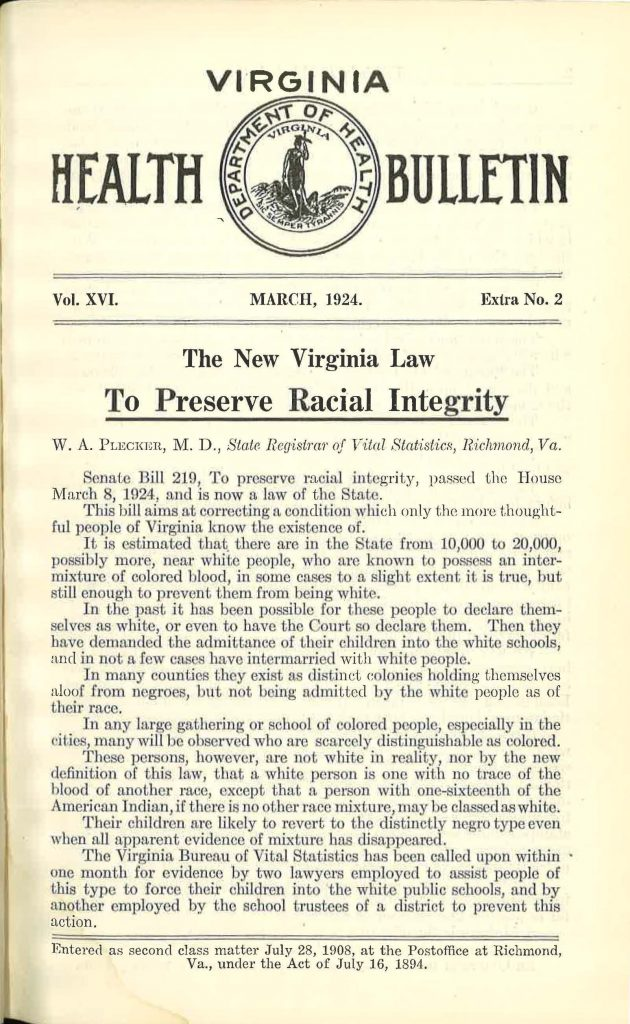

Many of the miscegenation laws created in colonial America created the framework for more discriminatory practices addressed in America’s Civil Rights Movement such as Brown v. Board of Education and Loving v. Virginia [16]. Through state and federal laws that have once existed in the US, it is important to see the government’s role in enforcing divisive structures based on blood that have impacted American society on a legal level, in addition to the social aspect.

This was issued by the state of Virginia to warn white citizens of the racial groups to avoid to prevent their offspring from becoming the “negro type”.

Viñas-Nelson, Jessica. “Interracial Marriage in ‘Post-Racial’ America.” Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, July 2017. https://origins.osu.edu/article/interracial-marriage-post-racial-america.

While many of the laws enacted were to prevent Black and white blood from mixing, many of them were rooted in creating division between other non-white racial groups and keeping the races separate to avoid any unity that could be formed between oppressed people [17]

As this essay briefly mentions in its earlier sections, the racialization of Black Americans varies from that of many other racial groups. The concept of blood in Black history is rooted in the principle of hypodescent, which refers to the automatic assignment of mixed race individuals to the racial status of the racially “subordinate” group, whereas blood in the context of Native American history is based on the principle of hyperdescent: referring to the practice of assigning those with mixed ancestry to the more dominant racial group. This process of hyperdescent positions Native American history as subtractive and is constructed so that the perceived number of Native Americans decreases as history progresses [18]. Although the specific racializations between Black people and Indigenous people, for example, may be contrasted, it is a part of a larger commentary that frames white people as the superior group. Throughout history, this policing has remained prevalent and has led to not only an exclusion from the lens of white society but has taken its form in the ways the Black community has perceived their own blood. This essay only focuses on how blood developed as a concept in the colonial period, but it is important to note that these ideas are the foundation for everything we see pertaining to blood in modern day America.

“The combination of these miscegenation laws with the principle of hypodescent consolidated and perpetuated the low-class positions of African Americans in much of the United States”

David Hollinger

Blood in Latinx American Culture:

Blood in Latinx history has been used not only to divide and distance Latinx people but it’s also been used to maintain systems of inequality that privilege white “blood”. During the Spanish colonization of Latin America, the Casta System was implemented [20]. It divided Latinos into rigid racial categories that elevated those with more European blood while suppressing those with more African and indigenous blood [20]. In the Casta System, blood held both a biological and socially constructed meaning, tying the idea of race and ancestry together. In this way, blood was used as a tangible tool that allowed white blood to maintain power and control.

The Casta System weaponized ideas of mixing blood to divide Latinos of varying ancestral roots– not dissimilar to the way blood quantum quantified and controlled Native Americans and the way the one-drop rule dehumanized and oppressed African Americans in colonial history. Many visual art that depicted the Casta System emerged during the 18th century, specifically the different combinations of “blood” or ancestry mixing to create different racial identities [21]. The Casta System forced people to mold themselves into categories based on the perceived race of their mother and father. These categories include mestizo, a child of European and Indigenous descent, and mulatto, a child of African and European descent [22]. Blood is quantified further with classifications like castizo, a child of ¼ Indigenous descent and ¾ European descent, or more simply, a child born between a European and a mestizo [22]. Just like colonialism forced blood quantum and the one-drop rule onto Native Americans and African Americans respectively, the Casta System dehumanizes and devalues non-white blood.

Ignacio María Barreda, Las Castas Mexicanas, 1777, oil on canvas, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Madrid, available from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ignacio_Mar%C3%ADa_Barreda_-_Las_castas_mexicanas.jpg, accessed December 10, 2024.

Looking at the function of blood in Latinx American history is particularly interesting in the way this social group combines Native American, African American, and European ancestry. As discussed earlier, colonial power has oppressed Native Americans through hyperdescent and has oppressed African Americans through hypodescent. Through the example of the Casta System, it is clear that hypodescent, or the practice of assigning a person of mixed race to the subordinate racial group, is used in Latinx American history [23]. In the Casta System, any blood that is not “purely” European casts the individual as “other” or not able to access the full privileges of “pure” Europeans [23]. Since Latinx American history involves the different combinations of Indigenous, African, and European ancestry, it is interesting how colonial power favored hypodescent instead of hyperdescent in this case.

Closing Remarks

Through this keyword page, we hope that readers are able to understand just how much “blood” shapes the history and the context we live in. Though it is most commonly perceived as the tangible thing keeping us alive, we hope that through exploring this page, an understanding of how blood has shaped, and continues to shape Black, Native American, and Latin American history is developed. The sections collectively examine how the concept of blood has been used to define and control identity: through blood quantum’s impact on Native American tribal identity, hypodescent’s role in the racialization of Black people, and the Casta System’s classification and dehumanization of Latinos. We have explored how these different categorizations have all functioned to elevate white control and power. We would also like to note that in our process of closely analyzing these different histories together, we have also recognized the confusion that accompanies it. This essay aims to explore how these racializations impact history exclusively in relation to whiteness but does not intently analyze these relationships between non-white racial groups. The concept of blood involves many complexities that this essay only begins to describe, but we hope that it works as a foundation for understanding blood to be the intersection of biological standards and socially constructed racial theories.

Contributors

- Ilana Brown

- Alyssa Garciano

- Kady Seck

Footnotes

[1] TallBear, Kim. “Genomic Articulations of Indigeneity.” Social Studies of Science 43, no. 4 (2013): 509–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43284191.

[2] Ashleigh Lussenden*, “NOTE: Blood Quantum and the Ever-Tightening Chokehold on Tribal Citizenship: The Reproductive Justice Implications of Blood Quantum Requirements,” California Law Review, 111, 287 (February, 2023). https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=analytical-materials&id=urn%3acontentItem%3a6822-V3B1-F8KH-X4KH-00000-00&context=1519360&identityprofileid=6WVBM651826

[3] Villazor, R. C. (2008). Blood Quantum Land Laws and the Race versus Political Identity Dilemma. California Law Review, 96(3), 801–837.

[4] Lussenden, “Blood Quantum and the Ever-Tightening Chokehold on Tribal Citizenship”, 111, 287

[5] Tallbear, “Genomic Articulations of Indigeneity.”, 509–33.

[6] Hollinger, David A. “The One Drop Rule & the One Hate Rule.” Daedalus 134, no. 1 (2005): 18–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027957.

[7] Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor | Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.” Utoronto.ca. September 8, 2012.

[8] Hollinger, “The One Drop Rule & the One Hate Rule.” 18-28

[9] Hollinger, “The One Drop Rule & the One Hate Rule.” 18-28

[10] Duany, Jorge. “Reconstructing Racial Identity: Ethnicity, Color, and Class among Dominicans in the United States and Puerto Rico.” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 25, no. 3, 1998, pp. 147–72. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2634171. Accessed 2 Dec. 2024.

[11] Hollinger, “The One Drop Rule & the One Hate Rule.” 18-28

[12] Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor | Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.”

[13] Hickman, Christine B. “The Devil and the One Drop Rule: Racial Categories, African Americans, and the U.S. Census.” Michigan Law Review 95, no. 5 (1997): 1161–1265. https://doi.org/10.2307/1290008.

[14] Hollinger, David A. “Amalgamation and Hypodescent: The Question of Ethnoracial Mixture in the History of the United States.” The American Historical Review 108, no. 5 (2003): 1363–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/529971.

[15] Cruz, Bárbara C., and Michael J. Berson. “The American Melting Pot? Miscegenation Laws in the United States.” OAH Magazine of History 15, no. 4 (2001): 80–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163474.

[16] Cruz, Bárbara C., and Michael J. Berson, “The American Melting Pot? Miscegenation Laws in the United States.” 80–84.

[17] Cruz, Bárbara C., and Michael J. Berson, “The American Melting Pot? Miscegenation Laws in the United States.” 80–84.

[18] Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor | Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.”

[19] Raheja, Michelle, et al. Native Studies Keywords. University of Arizona Press, 2015. Project MUSE. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/39810.

[20] Robert McCaa, Stuart B. Schwartz, and Arturo Grubessich, “Race and Class in Colonial Latin America: A Critique,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 21, no. 3 (July 1979): 421–33, https://www.jstor.org/stable/178539.

[21] Katherine Morrison, “The Colonial Efficacy of Casta Paintings,” NASKO 7 (2019): 190–202, https://journals.lib.washington.edu/index.php/nasko/article/view/15643.

[22] Susana B. Escobar Zelaya, “The Remains of Castas in Latin America,” Global Insight 1, no. 1 (2021): 1–8, https://globalinsight.journal.library.uta.edu/index.php/globalinsight/article/view/29/18.

[23] Arnold K. Ho, Jim Sidanius, Daniel T. Levin, and Mahzarin R. Banaji, “Evidence for Hypodescent and Racial Hierarchy in the Categorization and Perception of Biracial Individuals,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100, no. 5 (2011): 792–805.

Bibliography

Cruz, Bárbara C., and Michael J. Berson. “The American Melting Pot? Miscegenation Laws in the United States.” OAH Magazine of History 15, no. 4 (2001): 80–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163474.

Cuison-Villazor, Rose. 2024. “Blood Quantum Land Laws and the Race versus Political Identity Dilemma.” Ssrn.com. 2024. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1121828.

Duany, Jorge. “Reconstructing Racial Identity: Ethnicity, Color, and Class among Dominicans in the United States and Puerto Rico.” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 25, no. 3, 1998, pp. 147–72. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2634171. Accessed 2 Dec. 2024.

Escobar Zelaya, Susana B. “The Remains of Castas in Latin America.” Global Insight 1, no. 1 (2021): 1–8. https://globalinsight.journal.library.uta.edu/index.php/globalinsight/article/view/29/18.

Hickman, Christine B. “The Devil and the One Drop Rule: Racial Categories, African Americans, and the U.S. Census.” Michigan Law Review 95, no. 5 (1997): 1161–1265. https://doi.org/10.2307/1290008.

Hollinger, David A. “Amalgamation and Hypodescent: The Question of Ethnoracial Mixture in the History of the United States.” The American Historical Review 108, no. 5 (2003): 1363–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/529971.

Hollinger, David A. “The One Drop Rule & the One Hate Rule.” Daedalus 134, no. 1 (2005): 18–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027957.

Ho, Arnold K., Jim Sidanius, Daniel T. Levin, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. “Evidence for Hypodescent and Racial Hierarchy in the Categorization and Perception of Biracial Individuals.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100, no. 5 (2011): 792–805.

Leroux, D. (2018). ‘We’ve been here for 2,000 years’: White settlers, Native American DNA and the phenomenon of indigenization. Social Studies of Science, 48(1), 80-100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312717751863

Lussenden, Ashleigh. “NOTE: Blood Quantum and the Ever-Tightening Chokehold on Tribal Citizenship: The Reproductive Justice Implications of Blood Quantum Requirements,” California Law Review, 111, 287 (February, 2023). https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=analytical-materials&id=urn%3acontentItem%3a6822-V3B1-F8KH-X4KH-00000-00&context=1519360&identityprofileid=6WVBM651826

McCaa, Robert, Stuart B. Schwartz, and Arturo Grubessich. “Race and Class in Colonial Latin America: A Critique.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 21, no. 3 (July 1979): 421–433. https://www.jstor.org/stable/178539.

Morrison, Katherine. “The Colonial Efficacy of Casta Paintings.” NASKO 7 (2019): 190–202. https://journals.lib.washington.edu/index.php/nasko/article/view/15643.

Raheja, Michelle, et al. Native Studies Keywords. University of Arizona Press, 2015. Project MUSE. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/39810

TallBear, Kim. “Genomic Articulations of Indigeneity.” Social Studies of Science 43, no. 4 (2013): 509–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43284191.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor | Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.” Utoronto.ca. September 8, 2012.

Viñas-Nelson, Jessica. “Interracial Marriage in ‘Post-Racial’ America.” Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, July 2017. https://origins.osu.edu/article/interracial-marriage-post-racial-america.