Borderlands

Definitions

The simplest understanding of a Borderland can be determined by breaking down the word into border and land; it is land at or near a border. [1] Borders can be politically drawn from imperialism or segregation, defining land and people with physical and legal dividers. They can also be present within natural and geographical formations like mountains and oceans. However, defining Borderlands, and the people who live along them, as a binary separation bound to nationality and location misunderstands the complex identities often formed from an oppressive political convergence. Understanding Borderlands begins with questioning the historical origins of Borderlands and seeing their emotional and psychological impacts on communities along these lines.

Herbert Eugene Bolton coined the term Borderlands in his 1921 book, The Spanish Borderlands. [2] His term became popularized by scholar Gloria Anzaldúa’s 1987, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. [3] Her book focuses specifically on her own experiences growing up along the Texas-U.S. Southwest / Mexican border. She prefaces Borderlands as generally existing physically, wherever two or more cultures meet, including across class, racial, gender, and national lines. [4] Constantly existing in a fluid state, Borderlands are full of instability and contradiction, where ideas of oppression and liberation or feelings of fear and hope exist. Anzaldúa, who is not only Chicana but also multiracial (hence, Mestiza), Jewish, and queer, develops Borderlands to be applicable across these multiple identities, which she often communicated through poetry. [4]

In her work, Anzaldúa challenged and digested hierarchies within herself and her community, ultimately emphasizing the diversity and intermixing of her “New Mestiza” reality produced by colonialism and her activism. In the spirit of Anzaldúa’s work, Borderlands to us means challenging the colonial definition of territories and, in turn, seeking a deeper perspective, making room for the exchange of cultures, fears, and ideas along lines that separate land and identities.

Developments in Borderlands Theory

Borderlands theory continues to be undefined— a characteristic of the topic itself— but this does not mean the definition is any less powerful. Rather, Borderlands theory results from a large conversation in academia, particularly Latinx and Chicano studies, which only continues to contest and build upon itself. Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza is canon in Chicano studies; however, it has also received its fair share of criticism and misinterpretation. Scholar Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano makes a significant point that The New Mestiza garnered a lot of popularity among white feminists, who co-opted Borderlands to fit their narratives while ignoring or misunderstanding its political significance to the U.S. / Mexico border. [6] Furthermore, the popularity of Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza sparked a conversation within Chicano studies and activist spaces which questioned what non-Chicano audiences were interpreting as the “Chicano Experience”. This caused many Chicano scholars to produce work redefining Borderlands, particularly in areas where Anzaldúa’s work did not resonate with their experience and imagining of Chicano theory. Yarbo-Bejanaro summarized this tension, where, “two potentially problematic areas in the reception of Borderlands are the isolation of this text from its conceptual community and the pitfalls in universalizing the theory of mestiza or border consciousness, which the text painstakingly grounds in specific historical and cultural experiences.” [6] However, amidst this issue with interpretation, Anzaldúa created a foundation on which Borderlands theory was born, and inspired scholarship like Feminism on the Border: From Gender Politics to Geopolitics and the collection Criticism in the Borderlands: Studies in Chicano Literature, Culture, and Ideology. [6]

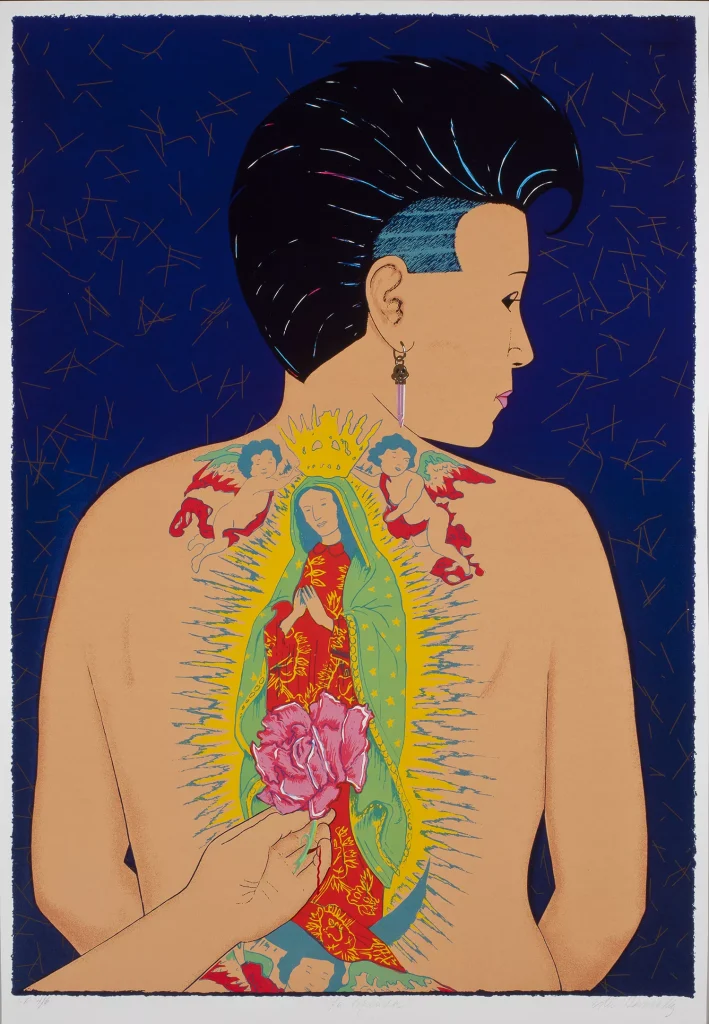

“La Ofrenda” by Ester Hernández places the motif of the Virgin Mary onto the canvas of a modern woman’s back, providing an image that addresses the intersections of faith, rebellion, culture, subculture, and authenticity. Showcasing Chicano voices is pertinent to the definition of “Borderlands” because these works give further dimension to the collective and individual experiences from which Anzaldúa drew her revelations in her book.

Other scholars of Borderlands view Borderlands as more expansive across race, particularly pertaining to Blackness— a topic that Anzaldúa cannot personally address. “Anzaldúa’s borderlands theory does not directly grapple with Blackness, or Black worldviews and geographies.” With this in mind, we want to emphasize the significance of Anzaldúa’s work but also remind ourselves that Anzaldúa’s writing is not where Borderlands theory ends, but rather where it begins. Borderlands theory has roots in a U.S. / Mexico context, but we believe that the definition and teachings of Borderlands theory can challenge hegemony around the world by revealing the ways imperialism politically and psychologically fragments communities and individuals.

Texas-U.S. Southwest / Mexican Border

A key aspect of understanding Borderlands in conjunction with Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora studies is challenging the power structures that produce today’s politically recognized borders. A large example of this that is relevant to the context of Borderlands theory is the history of the U.S. / Mexican Border, which is often taken for granted as a timeless firm line when it is actually a product of a violent conquest. Today, this is remembered with neutral language as the “Mexican-American War”, when in reality it was the result of President James Polk’s aspirations to fulfill manifest destiny, a term which was coined in the summer before the war began in 1846. [8] The war itself was characterized by the inequality in military might of the United States and Mexico, violence towards Mexican and Native communities, and the clear political objective of the United States to acquire more lands and potentially slave-owning states. The “war” itself was famously triggered by the murder of American Colonel Cross, whose head was found smashed near the Rio Grande, giving American politicians and people a reason to support a war. However, Cross’s death was a result of clear American provocation of the Mexican civilians, evident when an American army set up cannons on the border weeks earlier by order of the president.

A divine being is leading the settler-colonists toward the westward expansion of America, forcing the Indigenous people off of their land. The spiritual justification for Indigenous expulsion was also used to justify the “Mexican-American War” and the removal of Mexicans from their land.

The Mexicans were considered to have attacked first, however, even American Colonel Hitchcock wrote even before the incident, “I have said from the first that the United States are the aggressors. … We have not one particle of right to be here. … It looks as if the government sent a small force on purpose to bring on a war, so as to have a pretext for taking California and as much of this country as it chooses.” [8] Despite the dubious power imbalance that sparked the war, both the Whigs and Democrats favored the war, 174 to 14 in the House of Representatives and 40 to 2 in the Senate. Even liberals such as Abraham Lincoln, who challenged the legitimacy and morality of the war, still supported the end goal of acquiring the west and voted towards sending more troops. There were some anti-war activists, such as Henry David Thorough, the writer of “Civil Disobedience,” who was imprisoned for his refusal to pay his Massachusetts poll tax, knowing his tax dollars would support the bloodshed of innocent Mexicans. Frederick Douglass was outspoken in criticizing the cowardice of even those who opposed the war.

“None seem willing to take their stand for peace at all risks; and all seem willing that the war should be carried on, in some form or other.”[5]

Despite the evidence of mass murders and sexual violence toward innocent Mexican civilians, as well as military casualties on both sides, the war continued to be supported with the promise of acquiring California. After a number of bloody battles, triggered by the elites of America and Mexico, the war ended in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which set the border at the Rio Grande and exchanged 15 million dollars for what is now modern-day California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma [6].

Taking a closer look at histories like the U.S. / Mexico border makes it apparent what tools are used by an empire like the United States to sway public opinion for war and the acquisition of more land. The United States’ tactic of creating a warzone out of the U.S.-Mexico border mirrors what can be currently witnessed as the genocide in Palestine. In the borderlands, violence often goes unquestioned. It’s crucial to see how Borderlands are the direct result of imperial objectives which see land as promised for some, and uninhabitable for others based on race and nationality.

U.S. and Mexico Borderlands

A physical line is drawn to separate the U.S. and Mexico, and people who live along this line have distinct identities and characteristics that separate them from one another. Nevertheless, Borderlands unify these individuals across many differences to foster new lands outside those geographically and politically defined. In her book, Anzaldúa recognizes herself as a member of a Borderland and how her identity is shaped by it. She writes, “I am a border woman. I grew up between two cultures, the Mexican (with a heavy Indian influence) and the Anglo (as a member of a colonized people in our territory).” [3] Despite being born in Texas [12], her presence near the border constructed her internalized identity as a blend or “between” of cultures. Moreover, she hints at this “between” stemming from colonial history’s traumatic legacies and growth from colonization. Therefore, the physical line drawn between the U.S. and Mexico is blurred as individuals within Borderlands share their stories and lives with one another, allowing them to define their own lands, cultures, and identities.

Cities as Borderlands

“Oakland has been a borderland for some time—its Black and Latinx residents have been subjected to hyper-criminalization as part of the state’s carceral regime for decades”

Ramírez, Margaret M. “City as Borderland: Gentrification and the Policing of Black and Latinx Geographies in Oakland.” [15]

Oakland exists as a borderland. People of color in Oakland, and more specifically Black and Latinx residents, have been hyper-criminalized. Oakland was built on a system of displacement, surveillance, and carcerality. This means that Oakland has been acting as a borderland for a long time. People of color are surveilled, policed, displaced, and criminalized, which reflects the nature of borderlands. Those considered to be outside the norm are pushed out through violence, force, and other enforcement tactics. This enforcement creates tension and unrest in both internal and external ways. The people of color in Oakland feel unwelcome in what they consider to be their home and are conflicted in their state of being. Gentrification also occurs, raising rent prices and forcing residents to seek more affordable housing, causing their displacement. [15]

Ramírez, Margaret M. “City as Borderland: Gentrification and the Policing of Black and Latinx Geographies in Oakland.”

The city of Oakland used gang injunctions as tools to displace people in order to gentrify more effectively. The city of Oakland targeted desirable locations and designated them as gang injunctions, which was a “safety zone” created to manage gang activity by exercising certain constraints on members of gangs in that area. [15] These gang injunctions meant that people who were listed in a gang member database had their freedom and mobility in public spaces restricted. This control exercise furthered the feeling of isolation and not belonging among residents. All of this implies that gentrification can act as a process that creates or further emphasizes Borderlands in certain regions.

Schools as Borderlands

In pointing out her experience, we note that Anzaldúa’s experience may not fully encapsulate the experiences of individuals living along borders. Borderlands exist outside of the ones Anzaldúa and may not have the same impact on every individual. Moreover, borders and Borderlands are not to be solely understood in the context of country to country. For example, like Anzaldúa’s Borderland along the U.S. / Mexico border, schools can also be Borderlands through the blending of culture and teachings from Black youth (students) with White adults (teachers). [14] Although it is commonly understood that the role of a teacher is to teach their students and influence their academic and social understandings, students also play a teaching role in schools; racial prejudice has a deeply embedded history. [14] Schools can also become places where fear, hope, resistance, and oppression exist simultaneously. Through this, they often exist and act as Borderlands for Black youth in America. They are places where anguish and joy can coexist within school communities and individuals. Even at the smaller scale of schools, a Borderland acts as a psychological barrier, not just a physical one. People in communities struggle with Borderlands and how students, teachers, and community members grow closer, band together, and form a more “intimate” bond to survive in a Borderland. School Borderlands are less visible than larger-scale Borderlands like the U.S. / Mexico Borderlands. But recognizing this form of Borderlands gives voice to other forms of oppression and colonialism that still influence the many aspects of our world. In this article, the author discusses Borderlands in an urban context in Black communities and education. Black education and schooling are relevant to the discussion because colonialism is linked to anti-blackness in America. [13] Similarly, colonialism played its role in the conquest of Mexican and Indigenous land, creating sentiments against these groups as well. Outside of schools, there are few other contexts where lines between age, race, academic standing, and other characteristics of individuals can share ideas. In this understanding, we see Borderlands as being beyond geographical lands and territories and expanding the concept to meeting spaces for exchange and growth.

References:

[1] Definition of BORDERLAND. 2 Nov. 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/borderland.

[2] Bolton, Herbert Eugene. The Spanish borderlands: a chronicle of old Florida and the Southwest. Vol. 23. Yale University Press, 1921.

[3] Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands: La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 4th ed, Aunt Lute Books, 2012.

[4] Chávez, John R. “Aliens in Their Native Lands: The Persistence of Internal Colonial Theory.” Journal of World History 22, no. 4 (2011): 785–809. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41508018.

[5] The Young Center. “To Live in the Borderlands by Gloria Anzaldua.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSXh8-a8H4M.

[6] Yarbro-Bejarano, Yvonne. “Gloria Anzaldua’s Borderlands/La Frontera: Cultural Studies, ‘Difference,’ and the Non-Unitary Subject.” Cultural Critique, no. 28 (1994): 5. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354508.

[7] Hernández, Ester. “The Offering/La Ofrenda,” 1988. National Museum of Mexican Art Permanent Collection.

[8] Zinn, Howard. “We Take Nothing By Conquest, Thank God.” Essay. In A People’s History of the United States . New York, NY : Harper Collins Publisdhers, 2017.

[9] Crofutt, George A. “Manifest Destiny,” 1873. Library of Congress.

[10] Nichols, James David. “Introduction: The Making of Borderlands Mobility.” In The Limits of Liberty: Mobility and the Making of the Eastern U.S.-Mexico Border, 1–20. University of Nebraska Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvvndwp.5.

[11] “How Many US States Does Mexico Border?” Pinterest, September 16, 2017. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/281686151677504517/.

[12] CELEBRATING THE BIRTH AND LIFE OF GLORIA ANZALDÚA | TexLibris. 20 Sept. 2019, https://texlibris.lib.utexas.edu/2019/09/celebrating-the-birth-and-life-of-gloria-anzaldua/.

[13] TEDx Talks. “Moving Beyond the Chicano Borderlands | Michelle Navarro | TEDxMountainViewCollege” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1CSsK9kiYsQ.

[14] Fellner, Gene. “Schools as Borderlands: How Anzaldúa’s Concept of Borderlands Apply to Schools That Serve Black Communities.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 18, no. 2 (April 28, 2023): 377–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-023-10179-y.

[15] Ramírez, Margaret M. “City as Borderland: Gentrification and the Policing of Black and Latinx Geographies in Oakland.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38, no. 1 (May 1, 2019): 147–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819843924.

Bibliography

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands: La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 4th ed, Aunt Lute Books, 2012.

Bolton, Herbert Eugene. The Spanish borderlands: a chronicle of old Florida and the Southwest. Vol. 23. Yale University Press, 1921.

CELEBRATING THE BIRTH AND LIFE OF GLORIA ANZALDÚA | TexLibris. 20 Sept. 2019, https://texlibris.lib.utexas.edu/2019/09/celebrating-the-birth-and-life-of-gloria-anzaldua/.

Chávez, John R. “Aliens in Their Native Lands: The Persistence of Internal Colonial Theory.” Journal of World History 22, no. 4 (2011): 785–809. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41508018.

Definition of BORDERLAND. 2 Nov. 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/borderland.

Crofutt, George A. “Manifest Destiny,” 1873. Library of Congress. [1] Definition of BORDERLAND. 2 Nov. 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/borderland.

Fellner, Gene. “Schools as Borderlands: How Anzaldúa’s Concept of Borderlands Apply to Schools That Serve Black Communities.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 18, no. 2 (April 28, 2023): 377–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-023-10179-y.

Hernández, Ester. “The Offering/La Ofrenda,” 1988. National Museum of Mexican Art Permanent Collection.

“How Many US States Does Mexico Border?” Pinterest, September 16, 2017. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/281686151677504517/.

Nichols, James David. “Introduction: The Making of Borderlands Mobility.” In The Limits of Liberty: Mobility and the Making of the Eastern U.S.-Mexico Border, 1–20. University of Nebraska Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvvndwp.5.

Ramírez, Margaret M. “City as Borderland: Gentrification and the Policing of Black and Latinx Geographies in Oakland.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38, no. 1 (May 1, 2019): 147–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819843924.

TEDx Talks. “Moving Beyond the Chicano Borderlands | Michelle Navarro | TEDxMountainViewCollege” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1CSsK9kiYsQ.

The Young Center. “To Live in the Borderlands by Gloria Anzaldua.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSXh8-a8H4M.

Yarbro-Bejarano, Yvonne. “Gloria Anzaldua’s Borderlands/La Frontera: Cultural Studies, ‘Difference,’ and the Non-Unitary Subject.” Cultural Critique, no. 28 (1994): 5. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354508.

Zinn, Howard. “We Take Nothing By Conquest, Thank God.” Essay. In A People’s History of the United States. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers, 2017.

Contributors

Zoe E. Wells, Rowan A. Hunt, and Kaylee M. Lopez