Citizenship

Introduction

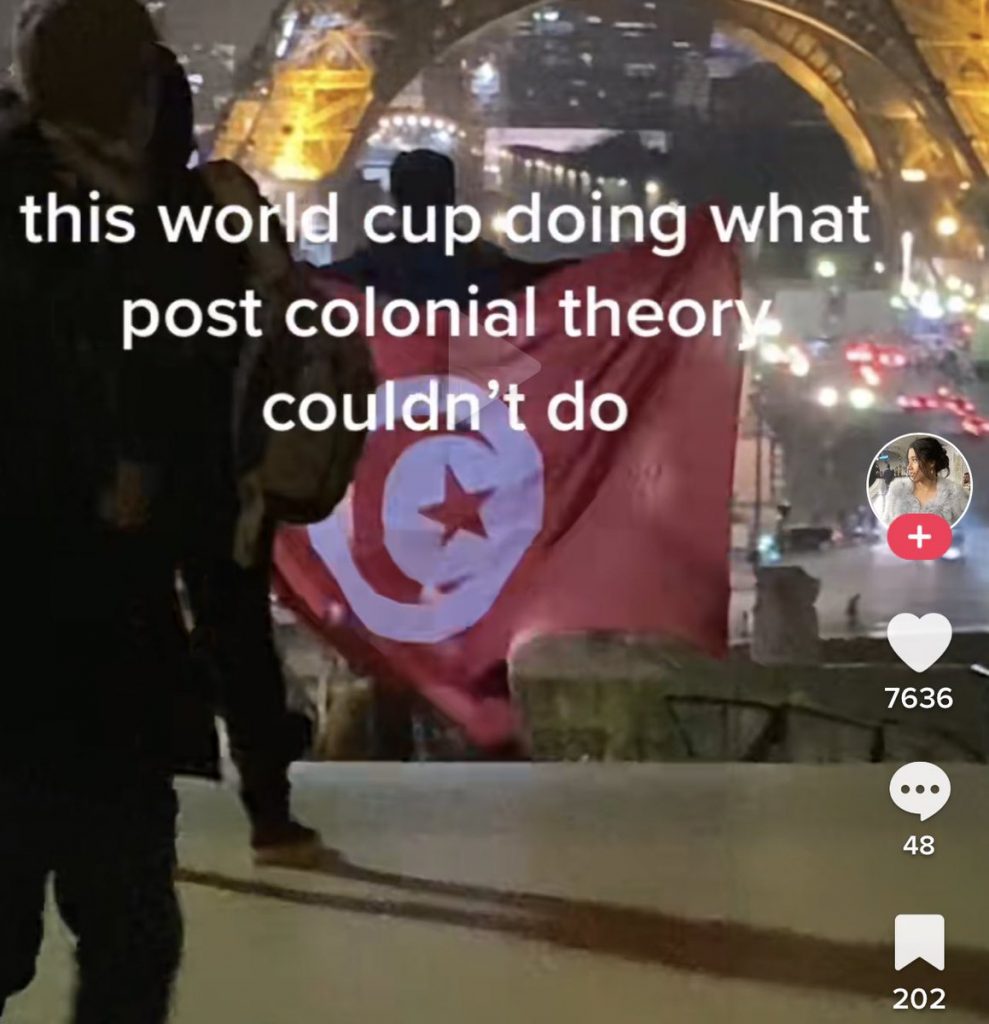

Recently, Morocco made soccer history as the first Arab and African nation to make the 2022 Fifa World Cup semifinals. Celebration for this win expanded past the Muslim diaspora, and resounded across barriers both literal and metaphorical. However, one key factor seems to draw people in. As put by Khaled Beydoun on Twitter — with adjustments made for formatting issues — “Morocco took down three colonial European nations in 10 days. Belgium. Spain. Portugal. If they defeat France. They’ll win something bigger than the World Cup: the hearts of formerly colonized people everywhere” (Beydoun).

Just a search through any social media network shows this international solidarity, to the point of declaring, “today I am Moroccan.” Many people have jokingly granted themselves temporary Moroccan citizenship, identifying themselves as part of an ingroup of unique multiplicities. But what does this show of solidarity for Morocco mean for citizenship as a whole?

Figure 2. Amro Ali, 6 December 2022, 1:20 p.m., https://twitter.com/_amroali

Definition

Citizenship can be defined through many lenses – political, legal, social, or civic to name a few. In the most basic terms, citizenship is the access or integration into an ingroup. Some may see these as confusing, however, they add nuance to our understanding of a broad and complex term. Through this page, we hope to explain and contextualize citizenship to offer an up-to-date interpretation of the concept. Citizenship is an abstract term – many people understand it solely as a legal belonging to a state, however, we hope to expand your understanding of this term through our website!

On this page, we first define political citizenship and the ways in which one acquires citizenship at birth. We then move on to less familiar forms of citizenship. Secondly, we look at contingent citizenship – a form of social citizenship. Then, we look at citizenship through the lens of its gendered and intimate forms.

Political Citizenship

According to Chantal Mouffe, citizenship is an individual’s membership in a political community that has been created by a state (ERIC Development Team, 1999). This membership often provides access to specific territorially bounded areas, some social services (depending on the state), and an array of rights and duties. Citizenship often serves to define the relationship which should be had between a citizen and a state; this differs greatly between countries.

Another scholar, T.H. Marshall defines citizenship in Europe through three key divisions: civil, political, and social. He argues that, over time, the state became incentivized to provide more rights and duties to its residents – this was done through the framework of citizenship (Dissent Magazine). Marshall’s understanding is important in helping us understand modern forms of citizenship. However, his Eurocentric approach fails to account for the different relationships that citizens have with the state. Specifically, not every state has provisions for the three key divisions he makes. For example, in Saudi Arabia, citizens have access to forms of social citizenship through services such as universal healthcare but do not necessarily have access to political citizenship as they lack the right to change elected leaders through elections.

The lack of any citizenship is known as being ‘stateless.’ The 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons defines this as ‘individuals who are not considered citizens or nationals under the operation of the laws of any country.’ This severely limits the agency and mobility of an individual.

Jus Soli vs Jus Sanguinis

Every country has provisions to grant citizenship at birth. This is often done through a combination of two doctrines: jus soli – also known as birthright citizenship – and jus sanguinis – citizenship acquired through descent or hereditary succession, depending on the state and its specific history.

The United States applies jus soli – this means that a birth certificate issued by any US state is a valid proof of citizenship. However, in a country with pure jus sanguinis, proof of a parent’s citizenship/residency status and proof of paternity/maternity would be the basis for acquiring citizenship. Globally, jus sanguinis is the dominant doctrine in citizenship allocation. Jus soli remains intact in much of North and South America.

Dimitry Kochenov problematises these practices in his book ‘Citizenship.’ In it, he argues that “once granted at birth, your citizenship determines the treatment, in law and in fact, you will receive anywhere in the world” (2019). Kochenov recognizes the role of citizenship in limiting mobility – often only citizens of a country have the indefinite right to remain in its territory. This benefits wealthy countries with high standards of living, however, it also “wields huge biopower by locking the world’s poor in the places where their economic power is nil and life expectancy extremely short” (2019).

He also criticises the historical role of citizenship in promoting exclusion:

“Although presented as an equally distributed given, citizenship is never and has never been neutral. The status quo it upholds always favors particular interests in a society. Historically, any citizenship status has always played a crucial role in policing strict arbitrary boundaries of exclusion, particularly on the basis of race and sex” (Kochenov 2019).

This documentary focuses on people who were born or brought to the UK while they were children. Despite feeling ‘British,’ they have not been able to regularise their citizenship/immigration status. It discusses the legal, psychological, and financial challenges they face by attempting to navigate the strict immigration rules of the United Kingdom.

Contingent Citizenship

First coined by the scholar Avtar Brah in Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities, contingent citizenship is used to denote the ambivalent legal and social status of immigrant communities, whose identity as citizens is partial, unstable, and vulnerable (Brah, 1996). It also refers to sociopolitical conditions in which entitled benefits of citizens are dependent — contingent — upon the jurisdiction of the state and national government. Under such conditions, governments may choose to extend/withhold benefits, or assign punishment based on whether or not citizens’ conduct and behavior is deemed appropriate by government standards (Ugolotti, 2022). In doing so, the government produces racialised, classed and gendered individuals who contribute to a palatable and idealistic image of progressiveness, vibrancy and diversity (Ugolotti, 2022).

Overall, contingent citizenship is a violent, multi-faceted concept in the sense that, by introducing the concept of “membership” to a country, there is motive to exclude non-desirable others. It is important to understand that citizenship rights and citizenship status itself are not interchangeable terms. Rogers Brubaker touches on this in his work Nationalism Reframed, where he revisits European countries as the birthplace of nationalism, and investigates how it has been used to reorganize politics, state/country boundaries, and the mixing/migration of people to a nation (Brubaker). Within this frame of thinking, citizenship is the key to maintaining the nation as an institution. As Brubaker summarizes it: “Its [referring to Citizenship] internal face, seen from within a single polity, is inclusive, universalist, egalitarian. Its external face, seen from the perspective of the global state system or of humanity as a whole, is exclusive, particularistic, inegalitarian” (Brubaker, 1996: 414).

Contingent Citizenship of Koreans in Japan

We can see one example of contingent citizenship manifest with the current status of Korean residents in Japan. Currently, they are the oldest foreign resident community in Japan, with the oldest residents dating from Japan’s colonization of Korea (1910 – 1945). Despite these numbers, only about 30% of the population has naturalized in the past 50 years — this number includes both foreign-born and native-born Korean residents (Chung, 2009).

Within Japan, ethnic minorities (mainly Ainu, Okinawans, and Burakumin) are physically indistinguishable from the Japanese majority, at least to the outside observer. Yet, Japanese citizenship policies are among some of the most restrictive of any nation. The Japanese concept of nationality is intertwined with a strong notion of homogeneous ethnic, racial, and national identity. In order to become fully naturalized as a citizen, applicants not only must renounce their other citizenship/country of origin but must demonstrate enough evidence of satisfactory cultural assimilation (Chung, 2009). In other words, their citizenship is contingent upon their ability to adhere to the requirements of a “good citizen” of each country, sometimes going so far as to change names for greater cultural assimilation.

Haji Oh is a Zainichi Korean artist whose art deals with questions of minority positionality, citizenship, belonging, memory, and family history through textile and fabric art. Like most Zainichi Koreans, she also has a Japanese name (Natsue Okamura), which she no longer goes by. For one of her artworks titled Wedding Dress for Minority Race (2000), she reconstructs a Korean hanbok from pieces of a Japanese kimono. Both of these clothes are typically worn at formal events, including weddings. While making this garment, Oh thinks about how to create an ethnic costume that represents the identity of a Zainichi Korean woman living in Japan, and what it means to be an ethnic minority. Through this reconstruction/recontextualization of fabric, she weaves together a symbol of cross-national hybridity of Zainichi Koreans in Japan.

Minority Race. 2000. Courtesy of the artist.

Photo by Seiji Tominaga

As a result of attending Japanese schools, Oh was not able to communicate well with her grandma. She was unable to speak much Korean — likewise, her grandmother spoke very little Japanese. Being Zainichi Korean was hard even at home. In 2004, she traveled to Jeju Island (her grandma’s hometown) in an attempt to explore cross-generational family history, memory, and identity. Born out of this field research, Three Generations (2004) is a photo triptych that aims to retrace and reimagine her grandmother’s journey from Jeju Island to Japan. Structurally, the image remains the same — it is always Oh standing on a road that vanishes behind her in Jeju Island. However, each photo depicts Oh wearing three different garments. In the first photo, Oh wears her grandma’s chima jeogori. In the middle, Oh wears a handmade garment. In the last photo, she wears her mother’s hanbok. The collective effect depicts the legacy of three generations of women in her family, and the strong connection between each of them. Despite the connection, the repetition of these images suggests the viewer (and Oh herself) can only attempt to imagine what her grandmother’s journey from Jeju and her mother’s return to Jeju decades later might have meant to them.

Photograph by Lee Seon Min.

The postwar Japanese government, despite implementing policies that stripped Koreans of their Japanese nationalities for naturalization, did not grant them full Japanese citizenship. Assuming that all Koreans in Japan would eventually return to Korea, the SCAP (Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers) made no clarification regarding their legal status. Koreans were then left as ambiguous “Japanese nationals,” which placed them precariously at the border between citizens and non-citizens. Thus, Japan was left without a uniform policy toward Koreans’ citizenship in Japan, and the SCAP’s wishy-washy responses to the “Korean problem” set the tone for the strained relationship that has persisted between Korean communities and the Japanese state (Chung, 2009).

Several early SCAP directives prohibited discrimination against Koreans and other ethnic minorities in sectors like employment and social welfare. Other later directives stated that Koreans were not under Japanese criminal jurisdiction. Despite these attempts at protection, the Japanese government exploited the ambiguity of their contingent citizenship status by enforcing surveillance and increasing police presence in Korean communities, all while denying them full citizenship rights (Chung, 2009). There was no real desire to naturalize Koreans into Japanese society — they were non-desirable, and to maintain exclusivity and purity, the Japanese government’s goal was always to have them return to Korea.

Gendered Citizenship

Gendered citizenship refers to the disparities in citizenship rights based on heteronormative histories concerning gender and patriarchy (van Doorn, 2013). A person who has gendered citizenship may say they experience sexism, misogyny, or transphobia, and so on.

As put by Anurekha Chari, gendered citizenship has three parts: “the binary of the private and the public, with the public referring to the material issues and the private to cultural matters… the framing of rights within the social structures of caste, class, and ethnicity…,” and societal differences “conceptualized in light of multiple patriarchies” . Here it becomes clear that citizenship is not a right, but a privilege that bars those nonconforming to the status quo. Although women have legal citizenship, their rights become emphasized in the private sphere (closed to a certain few), and controlled in the public sphere (access to all). In order to perform the role of a citizen, a woman must also play the mother/home. As a result of this gendering, citizens may become invisible citizens (Abu-Ras et al., 2022). The private sphere also gives less choice.

Although an individual may have political citizenship, their actual mobility through daily life suffers due to societal limitations. This can be literal mobile limitations such as safe type of areas or times to be out. A very blatant example comes from Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” where the main character Offred comments on these mobile limitations. She says,

“I remember the rules, rules that were never spelled out but that every woman knew: Don’t open your door to a stranger, even if he says he is the police. Make him slide his ID under the door. Don’t stop on the road to help a motorist pretending to be in trouble. Keep the locks on and keep going. If anyone whistles, don’t turn to look. Don’t go into a laundromat, by yourself, at night.”

Besides these limitations, other forms can manifest as dress codes (Aghasaleh, 2018), job opportunities due to gendered jobs (examples of feminine jobs being: teacher, secretary, nurse, waitress), or wage gaps. Medical attention also impacts mobility. Accessing gender affirming treatment and birth control as a non-cis hetero man can be difficult not just due to the medical professional’s biases, but also with legislation limitations as seen in Florida and Texas (Freedom For All). Sometimes, it becomes difficult to even get a reliable diagnosis is unreliable. For example, a woman with ADHD or Autism can be misdiagnosed with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder and more because studies for these disabilities are predominantly based on cis-hetero white men, which not only means that the criteria or understanding of the symptoms is extremely limited, but also the incorrect treatment for these misdiagnoses leads to long term costs, such as self esteem issues and exacerbated mental disfunction (Quinn & Mahdoo, 2014). Some mobile limitations may seem more “normal” than others, which goes on to show how indoctrinated these policies are in society. Others have a say, and ultimately control over one’s life direction simply for their body characteristics.

In order to win in a society made to support only a few, a marginalized individual must adopt the traits of those in power. Having a “shrill” voice compared to one that is low in register can drastically interfere with one’s initial perception. A soft voice is considered effeminate, low intelligence, and inexperienced while a deeper voice is authoritative, smart, and knowledgeable. Therefore, an individual with a soft voice may be more intentional about their pitch in a professional setting to be taken seriously (Peters, 2022).

Heihaizi, or Ghost Children

Heihaizi is a term representative of the unregistered children born under China´s One-child policy. Before this policy, leaders heavily encouraged population growth as a national investment. However, due to rapid modernization, a series of policies rolled out in the 1970’s, culminating in the first official One-child policy in 1980. The policy, besides its inherent name, included severe penalties. These ranged from financial to physical, such as forced sterilization. (one child policy film) Due to a cultural preference for male children, many families refused to care for a first-born girl, and in extreme cases committed femicide. This at one point led to a new policy that allowed for a second child if the first child was a girl (One Child Nation).

In less extreme cases, the extra unwanted children became ghosts. Consequently, as of now, the gendered ratio of China’s population is skewed. In 2021, the ratio was 104.9 males to 100 females, according to Statisca. While this gendered ratio is skewed, the national data does not include the heihaizi. There are at least 13 million heihaizi, and of that number, 70-80% are female (Votive).

As a heihaizi, one does not have any legal rights, as they do not legally exist. Medical care, job opportunities, education, and any other form of necessary mobility is practically impossible to access. The forms of mobility available thus are also not legal. The lack of mobility, especially for female heihaizi, leads to China having the highest suicide rates among adult women in the world.

Intimate Citizenship

Unlike the previous forms of citizenship, intimate citizenship (also known as sexual citizenship), offers a more egalitarian role to the individual. Similar to gendered citizenship, intimate citizenship “stresses the embodied and sexed nature of citizenship, consequently critiquing its heteronormative historical formations,” as put by van Doorn. This form of citizenship is not akin to intimacy, but a collective dialogue surrounding intimacies. Although personal, intimate citizenship forms through the public sphere, and as such, is prone to changes while still recognizing the past. Intimate citizenship offers a person security and autonomy. It’s a way to access mobility within a society that impedes it for those marginalized. Intimate citizenship ultimately is the closest method to escaping oppression without fully removing oneself from society.

Leather culture

One example of intimate citizenship is the queer community. In the U.S., one manifestation arises in leather. Leather, as a tool for community, has its origins in the military, and has developed to include a set of moral codes including sex. Leather further came into prominence in the early 1980s due to the AIDS epidemic, especially when its practices were blamed, which thus enabled the organizations of grassroots networks to combat HIV (van Doorns). This community-oriented care strengthened both the sense of community and sense of belonging. Intimate citizenship, using leather as an example, doesn’t require tangibility like policies to guide it. It can be more abstract without subtracting its concrete nature.

References

- Abu-Ras, Wahiba & Elzamzami, & Burgoul, & Al-Merri, & Alajrad, Moumena & Karhabanda,. (2022). ijerph-19-06638- Gender Citizenship- abu-Ras e t al., 2022. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19. 6638.

- Aghasaleh, Rouhollah. “Oppressive Curriculum: Sexist, Racist, Classist, and Homophobic Practice of Dress Codes in Schooling.” Journal of African American Studies 22, no. 1 (2018): 94–108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45200244.

- Amri, Laroussi, and Ramola Ramtohul. “Introduction: Gender and Citizenship in the Global Age.” In Gender and Citizenship in the Global Age, edited by Laroussi Amri and Ramola Ramtohul, 1–28. CODESRIA, 2014. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvk3gp5d.4.

- Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. Toronto, Ontario: McClelland and Stewart, 1985.

- Beydoun, Khaled. Twitter post, December 10, 2022, 8:11 p.m., https://twitter.com/khaledbeydoun

- Brah, A. (1996). Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203974919

- Brubaker, Rogers. Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511558764.

- Chari, Anurekha. “Gendered Citizenship and Women’s Movement.” Economic and Political Weekly 44, no. 17 (2009): 47–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40279185.

- Chung, Erin Aeran. “The Politics of Contingent Citizenship: Korean Political Engagement in Japan and the United States.” In Diaspora without Homeland: Being Korean in Japan, edited by SONIA RYANG and JOHN LIE, 1st ed., 147–67. University of California Press, 2009. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pnbnc.10.

- De Martini Ugolotti, Nicola. “Contested Bodies in a Regenerating City: Post-Migrant Men’s Contingent Citizenship, Parkour and Diaspora Spaces.” Leisure studies ahead-of-print, no. ahead-of-print (2022): 1–17.

- Dissent Magazine. ‘T.H. Marshall’s “Citizenship and Social Class”’. Accessed 4 December 2022. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/t-h-marshalls-citizenship-and-social-class.

- FitzGerald, David Scott. ‘The History of Racialized Citizenship.’, 2017. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8292b796.

- Groenmeyer, Sharon. “Rethinking Gender and Citizenship in a Global Age: A South African Perspective on the Intersection between Political, Social and Intimate Citizenship.” In Gender and Citizenship in the Global Age, edited by Laroussi Amri and Ramola Ramtohul, 317–38. CODESRIA, 2014. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvk3gp5d.16.

- Feng, Peter X. Identities in Motion: Asian American Film and Video. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

- Fourteenth Amendment | Browse | Constitution Annotated | Congress.Gov | Library of Congress’. Accessed 11 December 2022. https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/amendment-14/.

- Honohan, Iseult “Birthright Citizenship”. In obo in Political Science, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756223/obo-9780199756223-0344.xml (accessed 3 Dec. 2022).

- Jennison, Rebecca (2017). “Reimagining Islands: Notes on Selected Works by Oh Haji, Soni Kum, and Yamashiro Chikako”. Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas: 155-177. http://situations.yonsei.ac.kr/product/data/item/1553949880/detail/0bdB035e13.pdf

- Kochenov, Dimitry. Citizenship. The MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2019.

- “Legislative Tracker: Anti-Transgender Legislation Filed for the 2022 Legislative Session.” Freedom for All Americans. Accessed December 11, 2022. https://freedomforallamericans.org/legislative-tracker/anti-transgender-legislation/.

- Levy, Daniel, and Yfaat. Weiss. Challenging Ethnic Citizenship : German and Israeli Perspectives on Immigration. New York: Berghahn Books, 2002.

- Peters, Alex. “Unspoken Phenomenon: Why Women Are Deepening Their Voices in the Workplace.” Dazed. Dazed, March 10, 2022. https://www.dazeddigital.com/beauty/article/55558/1/unspoken-phenomenon-why-women-are-deepening-their-voices-in-the-workplace.

- One Child Nation. Amazon Studios, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/One-Child-Nation-Nanfu-Wang/dp/B0875WTZX5.

- Quinn, P. O., & Madhoo, M. (2014). A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in women and girls: uncovering this hidden diagnosis. The primary care companion for CNS disorders, 16(3), PCC.13r01596. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.13r01596

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. ‘Statelessness’. UNHCR. Accessed 4 December 2022. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/statelessness.html.

- Staff, Vocativ. “The Ghosts of China’s One-Child Policy.” Vocativ. Vocativ, August 8, 2014. https://www.vocativ.com/world/china/ghosts-chinas-one-child-policy/.

- “The Concept of Citizenship in Education for Democracy.” ERIC Development Team, 1999. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED432532.pdf. .gov/fulltext/ED432532.pdf.

- van Doorn, N. (2013). Architectures of ‘the Good Life’: Queer Assemblages and the Composition of Intimate Citizenship. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31(1), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1068/d9311

- Wildness. Electronic Arts Intermix, 2012. https://www.eai.org/titles/wildness.

- Yamamoto, Hiroki (2019). “Decolonial Possibilities of Transnationalism in Contemporary Zainichi Korean Art.” Situations: Cultural Studies in the Asian Context. 12 (1): pp. 107-128. doi:10.22958/SITUCS.2019.12.1.006.

- Zhou, Youyou. 2022. “How Migration Has Shaped the World Cup.” Vox. December 8, 2022. https://www.vox.com/c/world/2022/12/8/23471181/how-migration-has-shaped-the-world-cup.

Contributors

Nyaoga, Sibi

Sakamoto, Ava

Zhang, Michelle