Commodity

Introduction & Definition

The Oxford Dictionary defines a commodity as “a raw material or primary agricultural product that can be bought and sold; a useful or valuable thing.”[1] However, the scope of commodities extends beyond the exchange of physical products to encompass broader societal and cultural changes. A commodity can contain vast, multi-faceted information that reveals its historical, political, and cultural context. Starting in the 15th century, commodities, such as porcelain, tobacco, and sugar, traveled thousands of miles along global trade routes, influencing labor relations and migration patterns. The expansion of global trade networks was only possible thanks to technological innovations, such as the invention of large-ocean going ships. Newer commodities, such as smartphones and digital apps, are no longer limited to the confines of physical products. For a material to become a commodity, it has to go through commodification in which it is assigned a market value. However, commodification is often far more complex than a series of buying and selling. Today, the economy is characterized by the mass production and global sourcing and trade of commodities. Therefore, the study of commodities is deeply connected to a historical framework, consumer culture, international labor practices, and cross-cultural encounters.

Theoretical Framework: Marxism

Commodities and their production processes have consistently driven life-altering societal changes. One of the most influential scholars on the subject of commodities is philosopher Karl Marx. According to Marx, a commodity is anything “which through its qualities satisfies human needs of whatever kind” and it is the heart of capitalist production.[2] Marx is critical of commodification, a process under capitalism where things are assigned an exchange value in the marketplace that subjugates their use value. Use values represent the physical properties of a commodity and the human need it fulfills. On the other hand, exchange values reflect the worth of a commodity in comparison to other objects on the market. Under capitalism, many life necessities, such as food and water, became commodities and are thus only available to those who can afford their market price.

Historical Framework

Sugar, coffee, tea, and salt are key ingredients in our daily diets. We cannot imagine our lives without them. But these commodities became only widespread in Europe in the 1500s. In the Middle Ages most people consumed goods produced locally. With the advent of new advances in shipbuilding, however, European nations gained access to new and previously unknown products that were grown thousands of miles away and traded through market exchange. The emergence of new commodities that we take for granted today was tied to the rise of global trade networks that connected harbors in Europe to places in Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

The Commodification of Sugar: From a Luxury Product to a Widespread Commodity

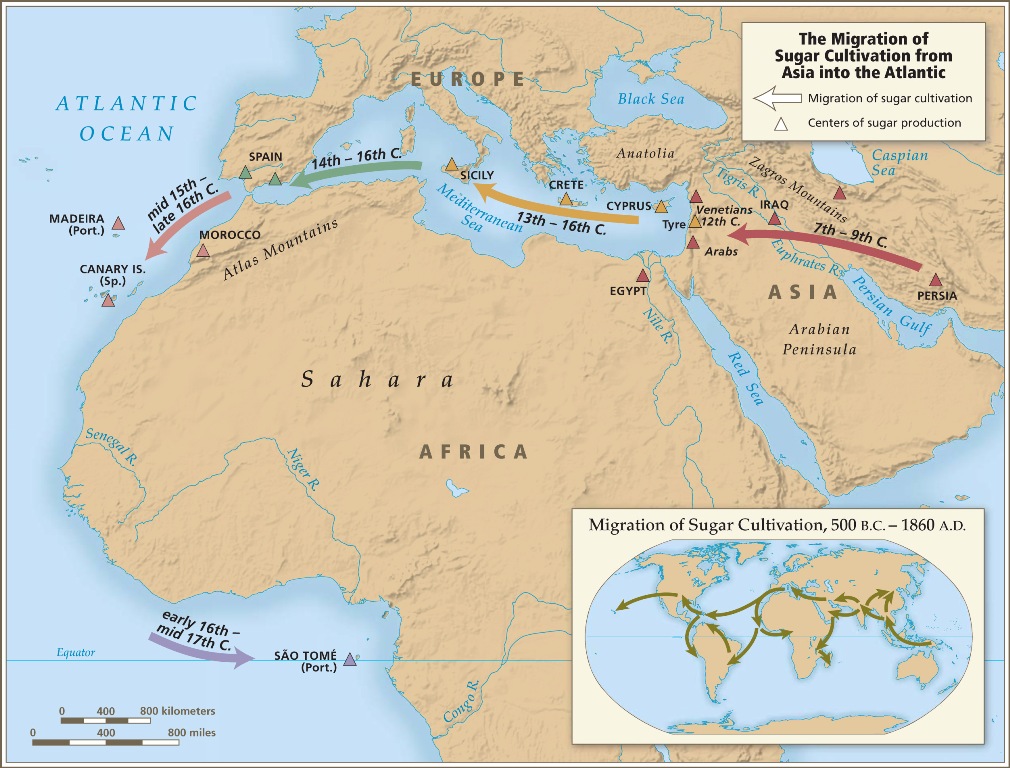

Historian Kenneth Pomeranz has argued that the increased demand for new products had huge societal, cultural, and environmental effects. A primary example is sugar. Sugar originated in the East, but over the centuries advanced westward, from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic islands, Brazil, and the Caribbean. As Kenneth Pomeranz observed: “Sugar was a truly international crop, combining an Asian plant, European capital, African labor, and American soil.”[3] The westward march of sugar and its global reach are illustrated in a modern map developed by the authors of the Atlas of the TransAtlantic slavetrade.[4] The influx of capital and the expansion of trade routes led to the mass production of these new commodities that had previously been made in small quantities for the very richest merchants and aristocrats.[5]

Starting in the fifteenth-century the Spanish and Portuguese developed plantations in Madeira, Sao Tomé, Brazil, and New Spain.[6] The Dutch followed in the 1630s when they took over control of Pernambuco, the northeastern province of Brazil, which was then the largest sugar producing region in the world. The increased sugar production changed the countryside into large plantations, leading to the degradation of the environment and natural resources. Sven Beckert, professor of American history at Harvard University, has described the enormous impact of lucrative commodities on land across the globe with the term “commodity frontiers.”[7]

In addition, the growing demand for addictive products like sugar affected labor patterns and the flow of migration. In the late 17th century, Haiti became a prominent sugar producing island. As in Brazil, sugar was grown in Haiti on plantations that relied on a brutal form of labor. Pomeranz explains: “Sugar brought the ancient labor form of slavery and the modern forms of industrial capitalism into a gruesome marriage.”[8] Europeans trafficked millions of African men, women and children to work on the plantations in Brazil, Haiti, and other islands in the Caribbean. Work was constant and highly regulated. The process included harvesting the sugarcane, crushing and extracting the juice, and crystallizing the liquid.[9] Because cut sugarcane spoils after one or two days, it had to be ground right away. The reliance on an imported labor force set in motion a huge migration of people. Of all enslaved peoples carried across the Atlantic between the early 15th century and the mid 19th century two thirds were put to work on sugar plantations.[10] Thus, the story of sugar illustrates how commodities were connected not just to economic forces, but also to societal and cultural changes.

The importance of sugar is revealed not just in the amounts imported into Europe, but also in the visual culture that developed around it. With the rise of sugar as a commodity, painted still lifes with sugary sweets and paintings of people consuming sweet delicacies emerged in Europe.[11] The centrality of sugar was also reflected in prints and maps. A 1624 map in a Dutch travel account published by Ian Canin shows the sugar-producing region of Pernambuco in Brazil.[12] It does not merely represent the area, but it also highlights the various stages of sugar production, carried out by enslaved Africans; laborers are working the land, operating a sugar mill, and pouring processed juice in vessels. In the harbor we see canoes and trading ships that eventually transported the sugar to Europe to sell it at a high profit. These maps reveal how commodities fundamentally changed the countryside, labor relations, and the local and global infrastructure. According to Sven Becket, such a transformation is inherent to commodity frontiers, writing: “We argue that commodity frontiers identify capitalism as a process rooted in a profound restructuring of the countryside and nature.”[13]

Commodity and Cross-Cultural Encounters

Scholars who expanded on Marx’s ideas concluded that commodities and the process of commodification are inseparable from colonialist expansion, during which a dominant marketplace determines the economic value of minoritized cultures and products.[14] The values of commodities are deeply ingrained in social, political, and cultural contexts. For example, minoritized cultural products such as art and fashion can become subjects of prejudice and stigma due to their ethnic expressions and thus decrease in market value. Simultaneously, the same products can be co-opted, appropriated, and consumed by dominant cultures. “Western” cultures have historically appropriated and recontextualized food, textiles, and art from non-Western cultures to cater to their tastes and sensibilities.

Theoretical framework: Orientalism

Orientalism, which framed non-Western commodities within a lens of otherness, often stripped them of their original cultural meanings, transforming them into objects of desire that symbolized luxury or exoticism for consumers.[15]

One example of orientalism is the application of Henna by American models and celebrities. Originating from Ancient Egypt, India, and North Africa, Henna is a reddish dye typically used in ceremonial body art for centuries. Through the advances of technology and media, traditional cultural products like Henna have entered mainstream popular cultures in Western countries such as the United States and contributed to the “Asian-cool” or “Indo-chic” aesthetic.[16] As celebrities and models begin wearing henna as a commercialized fashion item, the historical and cultural significance of henna is removed, reducing it to a “trendy” accessory. In other cases, henna as well as other cultural products such as clothing and accessories, became racialized commodities symbolizing a one-dimensional stereotype.

Other Orientalist commodities, such as martial arts and yoga, take more intangible forms that invite Western consumers to participate in an idealized form of Asian culture. For example, studios and classes on martial arts and yoga have once gained popularity in the United States, resulting in a lucrative industry. This has a nuanced impact on many communities. Cross-cultural migrations of commodities typically accompany the migrations of people. Historically marginalized communities have also participated in the commodification of their own cultural products in exchange for social capital and financial security, becoming ambassadors of racialized commodities.[17] For example, Asian immigrants in the US have historically opened restaurants, yoga, and martial arts studios in major cities, repackaging their cultures in exchange for a profit. Although this process has helped otherwise marginalized communities achieve financial security, scholar Nhi T. Lieu argues that the commodification of culture reinforces the fetishization and capitalist consumption of the Other, strengthening a racial status-quo that continues to disenfranchise minoritized communities.[18]

“With the expansion of global capitalism, the dominance of new media, and the advancement in digital technology, we are witnessing not only the commodification of ethnicity, but of bodies, food, music, and anything that can be marketed, made available for economic exchange, and consumed by those with access to capital…It is important to note what bell hooks reminds us, that the consumption of the other is legitimated by a racial structure that positions others to be consumed. The danger lies not in commodification itself but, as Marx would caution, in the fetishism of commodities.“

Nhi T. Lieu

Modern Commodities

Like agricultural products, technology is a common and essential item for daily life. Over the years, phones have evolved to become more compact and functional. The commodification of phones is particularly due to a lack of product differentiation, a short replacement cycle, and global mass production.[19] Most cell phones have standard features and interchangeable parts such as a touchscreen, an iOS or Android operating system, and pre-installed apps. In addition, new cell phone models are released every year, prompting most consumers to upgrade their phones every couple of years as older models become obsolete. Also, cell phones are fundamentally the same with small improvements that can be made to the camera, display, or battery. Nowadays, smartphones are mass-produced due to the constant demand for the latest model. With global retailers and online platforms, phones have become widely accessible. High-end smartphones have become a sign of wealth and status, further fueling the demand for newer and more advanced models.

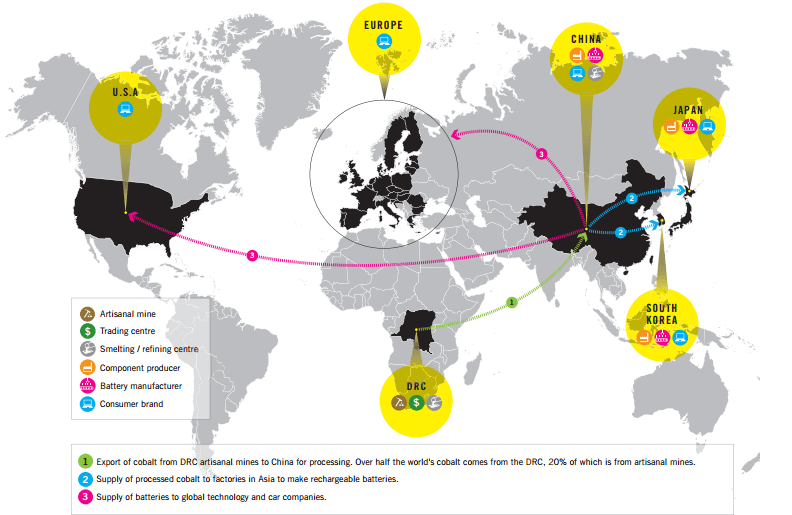

But like agricultural ingredients of modern life, smartphones and other electronic devices are part of a global economy that connects modern consumerism with exploitative labor practices. What is the labor that propels modern cell phones? The rechargeable batteries used in cell phones are made of cobalt ore mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the world’s largest producer of this metal. Amnesty International has reported that children spend long hours in the cobalt mines under dangerous conditions and are working without protective masks or gloves.[20] In addition, water and land is contaminated by the industry. Today, it is China, the world’s largest producer of lithium batteries, that refines the raw materials of cobalt sourced in Africa to produce the ingredients for our modern cell phones. Just like sugar, cell phones are part of a world economy. While in the 17th century Portugal dominated the production of sugar in Brazil and the Netherlands had cornered the sugar refinery market, today China has secured the global supply chain for batteries. Chinese companies own both Congolese cobalt mines and the battery factories located in China itself that turn cobalt into batteries. Thus, the commodity frontier for cobalt extends across the globe to include Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas. And just as in the early capitalist era, our modern consumption of desirable everyday commodities is fueled by exploitative labor and production practices taking places thousands of miles away.

Map showing how cobalt moves from mine to the global market, Amnesty International, January 19, 2016

Sugar Today

The popularity of other new commodities like tea, coffee, and cacao had an effect on the sugar market. Starting in the late 17th century, sugar was used as a sweetener in these bitter drinks, driving up demand. The British, in particular, turned to tea and tea-drinking became a national pastime. As James Walvin has shown, coffee became a central part of the everyday diet in the USA, leading to an ever increased reliance on sugar as a sweetener.[21]

With the rise of industrialization after 1850, sugar production around the world soared. The use of sugar in bitter drinks was expanded by sugary soft drinks. Today, sugar is one of the most widely consumed commodities. According to Khalil Gibrun Muhammed, Americans consume 77.1 pounds of sugar and sweeteners per person per year.[22] American Sugar Refining Company (ASR) is the world’s largest refined sugar company, and the maker of Domino Sugar.[23] It owns over six refineries that transform raw sugar into refined sugar, which is sold in stores and used in beverages. The Baltimore refinery produced 622,000 tonnes of sugar in 2023. Like in the early-capitalist era, the sugar market is not merely about buying and selling, it is also relying on commercialized labor. Rather than using locally grown beet, a modern source for sugar, Domino still uses sugar cane imported from Brazil, Barbados, the Congo, and other countries. The company has been criticized for its labor practices and the negative effect of sugar production on the environment. Indeed, the Bureau of International Labour Affairs reported that in 2024 sugar ranks among the highest agricultural products produced with forced and child labor.[24] Thus, something as common and enjoyable as sugar is one of the most powerful commodities in our modern era. Behind this “simple” commodity lies a bigger story of 16th century plantations, slave labor, global imports, mass production, profit, and modern exploitation.

References

Footnotes

[1] “Commodity Noun – Definition, Pictures, Pronunciation and Usage Notes | Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at Oxfordlearnersdictionaries.Com,” Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries, Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/commodity.

[2] Dino Felluga, “Terms Used by Marxism,” Introductory Guide to Critical Theory, Jan 31 2011, Purdue U, Accessed Nov 17 2024. <http://www.purdue.edu/guidetotheory/marxism/terms/>.

[3] Pomeranz, Kenneth., Topik, Steven. The World That Trade Created: Society, Culture, and the World Economy, 1400 to the Present. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2017.

[4] Eltis, David, and David Richardson. “2. Migration of Sugar Cultivation from Asia into the Atlantic.” Slave Voyages, January 1, 2022. https://www.slavevoyages.org/blog/migration-sugar-cultivation-asia-atlantic.

[5] Beckert, Sven, Ulbe Bosma, Mindi Schneider, and Eric Vanhaute. “Commodity Frontiers and the Transformation of the Global Countryside: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Global History 16, no. 3 (2021): 435–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022820000455

[6] The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015.

[7]Beckert, “Commodity Frontiers and the Transformation of the Global Countryside: A Research Agenda.”

[8] Pomeranz, The World That Trade Created: Society, Culture, and the World Economy, 1400 to the Present. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2017.

[9] Uil, H. De. 2014. “Biofuels for Transport.” In Future Energy, 215–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-099424-6.00011-9

[10] Eltis, David, and David Richardson. “2. Migration of Sugar Cultivation from Asia into the Atlantic.” Slave Voyages, January 1, 2022. https://www.slavevoyages.org/blog/migration-sugar-cultivation-asia-atlantic.

[11] The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015.

[12] Ian Canin, ed., Pernambuco, 1624, photograph, 1624.

[13] Beckert, “Commodity Frontiers and the Transformation of the Global Countryside: A Research Agenda.”

[14] Lieu, Nhi T. “Commodification.” In Keywords for Asian American Studies, edited by Cathy J.

[15] Chong, Sylvia Shin Huey. “Orientalism.” In Keywords for Asian American Studies, edited by Cathy J.

[16] Sunaina Maira “Temporary Tattoos: Indo-Chic Fantasies and Late Capitalist Orientalism.” Meridians 3, no. 1 (2002): 134–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40338549.

[17] Lieu, “Commodification.”

[18] Lieu, “Commodification.”

[19] Carton, Benjamin, Joannes Mongardini, and Yiqun Li. “Smartphones Drive New Global Tech Cycle, but Is Demand Peaking?” IMF, 8 Feb. 2018,

[20] Amnesty International. 2021. “Exposed: Child Labour Behind Smart Phone and Electric Car Batteries.” August 16, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/01/child-labour-behind-smart-phone-and-electric-car-batteries/.

[21] Walvin, James. Sugar: The World Corrupted, from Slavery to Obesity. United Kingdom: Robinson, 2017.

[22] Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. “The Barbaric History of Sugar in America.” The New York Times, August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/sugar-slave-trade-slavery.html.

[23] The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015.

[24] “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor.” n.d. DOL. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/reports/child-labor/list-of-goods.

Bibliography

Amallah, Nurlaillah Sari, Gun Gun Heryanto, and Adeni Adeni. 2024. “Commodification of Workers in Tempo Magazine.” International Journal of Social Science and Human Research 07 (03). https://doi.org/10.47191/ijsshr/v7-i03-54. Pg. 1929-1930

Amnesty International. 2021. “Exposed: Child Labour Behind Smart Phone and Electric Car Batteries.” August 16, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/01/child-labour-behind-smart-phone-and-electric-car-batteries/.

Beckert, Sven, Ulbe Bosma, Mindi Schneider, and Eric Vanhaute. “Commodity Frontiers and the Transformation of the Global Countryside: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Global History 16, no. 3 (2021): 435–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022820000455.

Canin, Ian, ed. Pernambuco. 1624. Photograph.

Carton, Benjamin, Joannes Mongardini, and Yiqun Li. “Smartphones Drive New Global Tech Cycle, but Is Demand Peaking?” IMF, 8 Feb. 2018, www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2018/02/08/smartphones-drive-new-global-tech-cycle-but-is demandpeaking#:~:text=Over%20a%20decade%20of%20spectacular,growth%20performance%20of%20several%20countries.

Chong, Sylvia Shin Huey. “Orientalism.” In Keywords for Asian American Studies, edited by Cathy J.

“Commodity Noun – Definition, Pictures, Pronunciation and Usage Notes | Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at Oxfordlearnersdictionaries.Com.” Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/commodity.

Cox, Clyde. The Value of Commodities. 2015. Photograph. Slide Player. https://slideplayer.com/slide/8825252/.

Schlund-Vials, Linda Trinh Võ, and K. Scott Wong, 182–85. NYU Press, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt15r3zv2.50.

“Emissions of Greenhouse Gases in the Manufacturing Sector.” Congressional Budget Office, 1 Feb. 2024, www.cbo.gov/publication/60030.

Eltis, David, and David Richardson. “2. Migration of Sugar Cultivation from Asia into the Atlantic.” Slave Voyages, January 1, 2022. https://www.slavevoyages.org/blog/migration-sugar-cultivation-asia-atlantic.

Felluga, Dino. “Terms Used by Marxism.” Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. Jan 31 2011. Purdue U. Accessed Nov 17 2024. <http://www.purdue.edu/guidetotheory/marxism/terms/>.

Itzchak E. Kornfeld. “Water: A Public Good or a Commodity?” Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law) 106 (2012): 49–52. https://doi.org/10.5305/procannmeetasil.106.0049.

Lampland, Martha. “The Value of Labor.” 2023. University of Chicago Press. December 22, 2023. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/V/bo23935313.html.

Lee, Chermaine. “A Closer Look at Smartphone Pollution.” FairPlanet, 14 Feb. 2023, www.fairplanet.org/story/smartphone-pollution-electronic-waste.

Lieu, Nhi T. “Commodification.” In Keywords for Asian American Studies, edited by Cathy J.

Schlund-Vials, Linda Trinh Võ, and K. Scott Wong, 29–30. NYU Press, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt15r3zv2.11.

“List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor.” n.d. DOL. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/reports/child-labor/list-of-goods.

Maira, Sunaina. “Temporary Tattoos: Indo-Chic Fantasies and Late Capitalist Orientalism.”

Meridians 3, no. 1 (2002): 134–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40338549.

Mannur, Anita, and Pia K. Sahni. 2011. “‘What Can Brown Do for You?’ Indo Chic and the Fashionability of South Asian Inspired Styles.” South Asian Popular Culture 9 (2): 177–90. doi:10.1080/14746689.2011.569069.

“Modern Marvels: How Sugar Is Made (S11, E52) | Full Episode | History.” YouTube, April 3, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9Tp7ICG1hg.

Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. “The Barbaric History of Sugar in America.” The New York Times, August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/sugar-slave-trade-slavery.html.

Nash, June. “Global Integration and the Commodification of Culture.” Ethnology 39, no. 2 (2000): 129–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773839.

Pomeranz, Kenneth., Topik, Steven. The World That Trade Created: Society, Culture, and the World Economy, 1400 to the Present. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2017.

The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Uil, H. De. 2014. “Biofuels for Transport.” In Future Energy, 215–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-099424-6.00011-9

Walvin, James. Sugar: The World Corrupted, from Slavery to Obesity. United Kingdom: Robinson, 2017.

Contributors

Hongru Chen

Angelina Kim

Derek Price