Community: ‘A group of people living in the same place or having a particular characteristic in common’

Google / Oxford Languages

Defining ‘community’ is no easy task, so the google definition (sourced from Oxford Languages) of community introduces the very broad term in an easily digestible manner. But we didn’t need that definition – community is an incredibly common term and word, one that is understood by the general public as having a clear definition. Communities are groups of people. They are wholes that consist of individuals. The term ‘community’ has a very deep history, however, with tons of nuance and depth, shifting and changing with the times. Communities, those have also changed over time – both with how people form and identify with those communities. So further than the google definition, which holds importance in and of itself as the general consensus for its definition, what is community?

Definition

There are many ways to interpret community, and although this is by no means an all encompassing definition, one way to define community is as:

A collective group of individuals identified by least one characteristic shared across all group members. Community is often associated with ideas of social relationships and provides feelings of companionship and/or belonging.

History

The past uses of community as well as its origins are vitally important to understanding the ways in which community is used in the present, and the different connotations it has with shifts in global politics and social norms. There are two distinct lenses with which to view the history of the term. The first lens is the etymological and primary usages of community – linguistic roots of the term and how those roots have shaped its meaning, both in creation and in its initial purpose. The first academic use of the word was in sociology, and over time the term has become a household term. The other lens is the functionality of the term, namely how the term ended up being used. The main distinction here is the shift from predetermined communities to chosen communities. The two are very intertwined, as of course the origin of the term and its intended purpose shaped its ensuing usages, but it is also incredibly important to understand how global modernization – socially, economically, culturally, and technologically – has changed the usage of the word.

In The Word

Far before the contemporary term of “community” was conceptualized, discussion about building social connections and groupings have proliferated human civilizations for a long time. In the 3rd century BC, Greek thinker Aristotle claimed that communities should be organized around the common good, and in his theories surrounding fundamental human relationships. [1] In China, famous philosopher Confucius debated the possibilities of the Small Tranquility and the Grand Union, both ideologies about how possible it was to achieve communal solidarity in various societies of different types and sizes. [2] These ideas of interrelationships and togetherness had significant influence on modern interpretations of what “community” means today.

In Scholarly Thinking

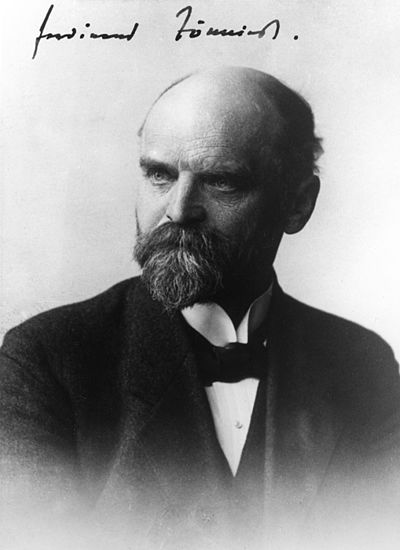

Etymologically, the English term “community” is derived from the Latin roots of communitas, meaning “fellowship, community, of relations or feelings”, and communis, meaning “common, public, general, shared by all or many”. [3] Breaking down communis even further, munis is a Latin term related to the act of providing services, and also serves as a root to the word “municipal”, further implying that ideas of community and governance/policy for cities/states have been tangled with each other for millenia. [4] The term “community” first entered academia through the field of sociology, when scholar Ferdinand F. Tönnies developed his theory of Gemeinschaft (German for community) and Gesellschaft (society) in 1887. [5] These two concepts were characterized as opposite ends in a binary, where Gemeinschaft defined the beginning stages of a society when people were tied together by close-knit connections, and Gesellschaft described the less personal relationships that were more common in later stages of a society when people were increasingly motivated by feelings of self-interest and rivalry. [6] Along with other European philosophers of that time (Karl Marx among them), Tönnies preferred Gemeinschaft because he was concerned about the rise of urbanization and capitalism accelerating humanity’s trajectory towards individualistic Gesellschaft culture. [7] As more people moved to the cities, he worried that the disconnection he observed in urban neighborhoods disrupted the unity he saw in rural neighborhoods, threatening the benefits that came with living in a society geared towards Gemeinschaft and community. [8]

When forces of urbanization and immigration flowed over to the United States, these ideas proposed by Tönnies flowed over as well. [9] American scholars in similar social science fields applied these findings to urban and rural neighborhoods in the States as well, and the study of how communities formed, integrated, developed, and affected social class structure spread into several disciplines (such as psychology, medicine and public health, anthropology, etc.) into the 20th century. [10] Eventually, the term’s usage expanded past academia into everyday use as well, and we can see various examples of its growing ubiquity through the history of communities in the United States.

In The Word’s Usage

Paralleling the etymological evolution of the term community is the change in communities themselves. The most crucial change in the history of the definition and usage of community is its expansion from closed and pre-determined to open and chosen. Before modern avenues of communication existed, humans connected largely based on shared location and identity. Community, then, was in part a survival mechanism, useful in serving the human need for interpersonal connection and social organization.

In his article “Community Development in America: A Brief History,” Brian M. Phifer explores the inception of community in America, describing its development as “an organized, purposeful, self-help activity”. [11] This is due in part to the expansive rural life of America, which was dependent on self-governance; communities formed in these rural towns so the town could together improve the lives of its inhabitants. Though this radical self-organization was largely unique to America, people formed communities through cohabitation all over the world, as community is a natural outgrowth of the social contract.

Communities and exclusivity/exclusion

This definition of community in early America excluded enslaved people that were not permitted to be in community with white people. This complicated the idea of community as simply a result of proximity. Enslaved people were forced to form their communities as a reaction to oppression; they grouped together not only because they lived with one another, but also because they shared a common struggle and a shared wish for freedom. [12]

It was globalization that catalyzed the modern understanding of some communities as chosen. As religious, social, and political beliefs passed over borders, so did communal bonds. More complex and international communities often formed around intellectual or political similarities. Dismas A. Masolo explores this shift in his article “Community, Identity, and the Cultural Space,” writing, “Communities are no longer viewed as fixed entities, but rather as open-ended and amorphous groupings definable more by the organizing beliefs, principles and practices than by the bodies which inhabit them.” [13] Through technology, social media, and culture exchange, people have been exposed to ideas they would have never been aware of in an earlier era. This has opened doors for individuals to be able to explore which identity groups they feel best represent themselves, and join those communities through their own will.

globalization and modernization

Historically, this has manifested most notably through identity groups and social activism causes. Take, for example, diaspora communities. The opportunity for members of a diasporic identity group to be in relationship with their home country and ancestors is a new tool aided by transnationalism. Of course, globalization has been intensely destructive for these same communities.

Beyond further engagement with one’s born ethnic identity, modern community also takes the form of groups bound by a commonly chosen identifier. This is exemplified by Effective Altruism, a self-described “research field and practical community that aims to find the best ways to help others, and put them into practice”. [14] Through the internet, a community has formed around a common set of beliefs. This arc is a common one in the formation of modern communities.

Into the Now

In essence, it is of immense importance to understand the modernization of the world we live in when examining groups of people and the ways in which individuals adhere to those groups. In stark contrast to the more traditional forms of community in rural areas, urban communities have become a large point of discussion. The importance of geography wanes as new modes of communication lead to international and widespread communities that see beyond conceptual boundaries, although geographical communities still persist within urban contexts. That is to say that ‘community’ has managed to escape its original intended meaning a small bit, stretching beyond simply collections of people in a geographic setting as it has been formed through adversity, across international and creative boundaries. Following its sociological conception, ‘community’ has become a basic word understood across the world as one that connects people, and in the discussion section, we will further explore some of the modern applications of community that have shaped themselves out of its past.

Discussion – Community in the Now

Community Organizing & Activism

Over the past few decades, the term “community” has become more popularized in social movements and activist spaces. In the 1980s, the concept “communitarianism” developed into a political movement in the United States and England that emphasized establishing an “us” mentality in society, where each person has a commitment to supporting public institutions and maintaining a common sense of morality. [15] One of the leading proponents of communitarianism, sociologist Amitai Etzioni, argues that communities should not be defined as individuals with separate motives that happen to be lumped into the same space. [16] Instead, communities should be defined as a collective group of people that share interests and can act together, and this definition is the reason communities can be so powerful. By limiting the idea of personal gain or singular needs, the collective entity of a community can achieve political and moral objectives on a national level. [17] Communitarianism believes that community is what brings even the most extreme and divergent people together, and that focusing on our ties with one another will bridge differences and move populations forward.

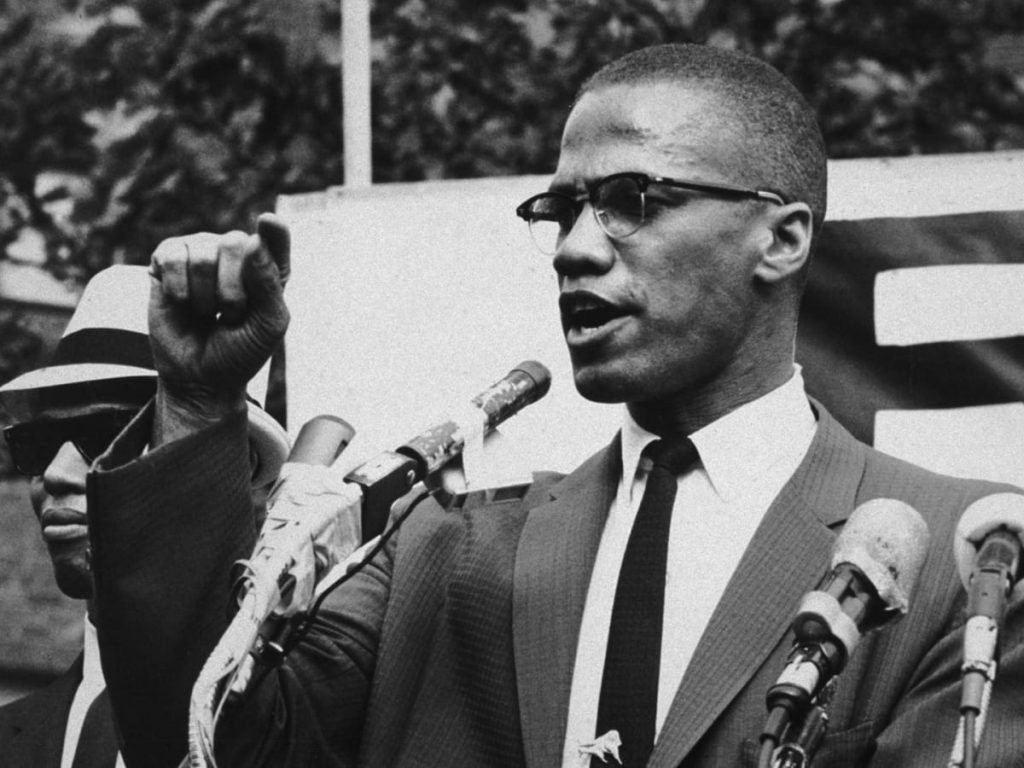

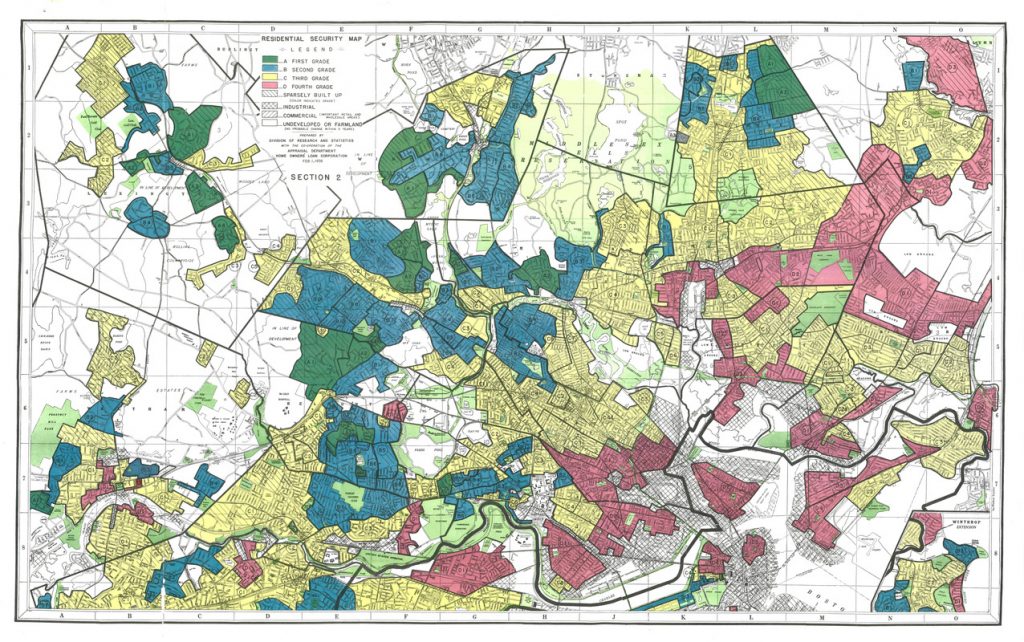

This sentiment is echoed in the way “community” has worked its way into other political and social movements, where the term is repeatedly used as a mechanism to push liberal beliefs. For example, racial justice movements tie the concept of community closely with coalition-building, a method for activists to foster solidarity between groups of marginalized peoples. Racial minorities in the United States, which are inherently outnumbered and whose experiences are dismissed as coming from the voices of too few, rely on creating bigger communities and networks in order to increase their presence against the white majority. Before the communitarianism movement of the 1980s, leaders fighting for racial equality like Malcolm X often used the term “community” to galvanize Black individuals behind their collective African American identity. [18] In his famous speeches to the masses, he drew on shared experiences like redlining, white flight, failed and white supremacist education/welfare systems to form a Black community identity. [18] He created an “us” mentality similar to communitarianism, but he pitted “us” against “them” to unite activists against a common enemy, the white man. [20] In this manner, X utilized a more confrontational definition of community, which tracks with his segregationist views that racial justice could only be carried out by those who experience racism, or those who were nonwhite.

Although community is not used so definitively to describe harshly opposing sides in present activist spaces, it is still used to recognize groups of people with marginalized identities. Today, grassroots activists usually call themselves “community organizers” as a sign of their values that prioritize ideas of the collective good and communal resources at the forefront of their work. Even in our lives as college students, we see the term crop up in areas next to a lot of similar spaces and institutions that claim to be pushing for progressive action. For instance, at Tufts, the university’s DEIJ policies, affinity spaces (such as special interest housing), and even official statements from the president’s office all center the word “community” to describe the individuals they are serving. More than a simple term and definition, community is a means for people who are discriminated against to take up more space in systems that force them into narrow social and economic positions with little power. Thus, for activists, community is not just a form of emotional support or networks to expand one’s social life; it is a matter of survival in the face of oppression that threatens their existence.

Geographic and Localized Community

Although the prerequisite of proximity in terms of community building is much less evident in the modern day of technology and fast-paced communication, community forged out of geographic closeness is still one of the primary forms of community formation. It is important to think about community, largely but not exclusively in urban spaces, as an “inherently geographic” term rather than one that can be geographic. [21] There are many ways in which this manifests itself, from the sense of pride manifested in a spatial identity such as Parisians or New Yorkers to global Indigenous connections to their lands. There are also ways in which people are forced to create community out of geographically based necessity due to a lack of access to community elsewhere. This has ranged from slaves forming prayer groups among themselves and to redlined communities who have been denied movement out of their neighborhoods. It includes migrants at the United States and Mexico borderlands who have traveled from south and central America and have been trapped in border cities in Mexico, able to see the other side but with nowhere else to go. When people are trapped in a place like this, groups of people who are discriminated against in uniform fashion, regardless of their differing pasts and historical contexts, they form communities.

That is not to say that community is only formed out of necessity – rather it is formed more broadly by the idea of shared experience. Within the context of localized disciplines, like primary health care for example, or public school faculty, community as a geographic concept, becomes a tool to foster connection and intimacy. [22] Having a doctor or a teacher who understands the geographic nuances of the space you are from greatly improves that relationship. When looking at these examples, it is apparent that using a model without regarding geography as an important factor is very detrimental; communities with less access in general – to transportation, to public service installations, to political power – will be ignored and will thus have less access to health care and education. [23] Those communities in urban spaces with less access in most cases can be traced back to redlining and other racist zoning laws that in the past relegated black and brown communities to economically worse areas.

Despite their abandonment, these laws have kept the economic mobility of black and brown communities extremely low. The formation of these “spatial [phenomena]” such as neighborhoods and boroughs in urban areas created connotations along with them, certain areas being labeled ‘dangerous’ or ‘safe’ based on what groups live there. [24] There is a lot of nuance in this formation of community, as stronger forms of community are often born out of these marginalized groups, but these groups are also created by the oppressors in order to form and reaffirm social hierarchies. Regardless of their formation, however, it is very important to regard neighborhood formation, general urban connotation of different cities, areas within cities, or even countries, as geographically based biases, formations and finally, communities.

Community Art

The application of art to communities takes many forms. Individual artists can influence a community with their public artwork; communities can use art to make political statements and demands; art may be created by and within a community in order to make internal changes inside of the group; art can even itself form a community. In all of these manifestations it is clear that art and community influence one another greatly.

The idea of an individual artist kindling social dialogue and influencing a community is exemplified in Pictures of Garbage, an art project in which the photographer Vik Muniz collaborated with garbage pickers just outside Rio to create photographic portraits of them. The purpose of this project was not only to shed light on the lives of this Brazilian class of workers but also to help them “take charge of their lives, while giving them a new perspective on the world through art”. [25] Muniz, who participated in a film about his project, spent years in Brazil building relationships with the community. This example sheds light on the power of an external artist to cause waves in a community, opening an door to further self-expression.

By accessing a platform through art, the garbage-collecters were able to define themselves as a community with many shared struggles and goals. Muniz helped to foster bonds with this community because of his own identity as a Brazilian, proving the power of geographic community in creating trust out of a feeling of shared experience.

Perhaps the most powerful form of community art is that which is created to inspire change. In her article “An Introduction to Community Art and Activism,” Jan Cohen-Cruz writes, “community art projects share activism’s commitment to collective, not strictly individual, representation. Moreover, as concerns communities of place, artists with strong geographical bonds garner particular opportunities for building alliances when activism is a goal”. [26] Often sharing geographical and cultural similarities, those within a community in turn are more likely to share similar political values and goals. Art can be an important form of protest in advocating for these goals. Take the Robert E. Lee Statue in Richmand Virginia. This statue is a confederate monument, but has in recent months transformed into a site where Black Lives Matter activists have written, painted, sculpted, their ideas into a “kaleidoscopic display of communal, collective action”. [27] This sculpture represents art created by an activist community, but also shows how the art itself can form a community through its own power and influence. As mentioned in the community activism section, much change that comes out of communities is aimed towards furthering the collective good, a fact clear in this example.

A community may create art not only to make a statement but also to uplift and benefit themselves. This is exemplified in the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, a project which employs artists and commissions communities within Philadelphia to create thousands of murals. The goal of this program is to uplift individuals, public spaces, and the community of Philadelphia as a whole. [28] According to the article “Creating Community” by Seana S. Lowe, communal art is “a ritual essential to building a sane society… ‘collective art is shared; it permits man to feel one with others in a meaningful, rich, productive way’”. [29] The act of making art together is essential to forming strong bonds in communities. It bonds people and creates the feeling of unification. This act can reinforce geographic communities, as seen in Philadelphia, like decorating a shared home can reinforce a family unit. It can take the form of activism or can simply be a reflection of common experience; either way, creating art collectively benefits the collective.

Reflection/Closing Thoughts

Through our collaborative WordPress page, we hope our readers have realized the key role these various meanings of community play both in their personal lives and in the broader societies that they live in. As shown through applications of visual art, neighborhood groups, and grassroots organizing, community articulates the instinct humans have to build relationships with one another in order to accomplish goals together. As we move forward, the meaning of community continues to evolve— with technology developing new forms of communication and our connections becoming less restricted by geography, we are empowered with the opportunity to choose the communities we want to be a part of. As you do so, reflect on what your own definition of community is and think about the intentional ways you can support yourself and others to build community, especially those with marginalized identities. We must not only maintain and nurture the relationships we have with individuals, but also the broader relationships between various groups that make up the fabric of a caring and interconnected global community.

- No categories

What does community mean to you?

Media

Identity & Community (There is no “I” in “Sea”)

Brenda Shaughnessy – 1970 –

I don’t want to be surrounded by people. Or even one person. But I don’t want to always be alone.

The answer is to become my own pet, hungry for plenty in a plentiful place.

There is no true solitude, only only.

At seaside, I have that familiar sense of being left out, too far to glean the secret: how go in?

What an inhuman surface the sea has, always open.

I’m too afraid to go in. I give no yes.

Full of shame, but refuse to litter ever. I pick myself up.

Wind has power. Sun has power. What is power’s source?

* * *

There’s no privacy outside. We’ve invaded it.

There is no life outside empire. All paradise is performance for people who pay.

Perhaps I’m an invader and feel I haven’t paid.

What a waste, to have lost everything in mind.

* * *

Watching three mom-like women try to go in, I’m green—I want to join them.

But they are not my women. I join them, apologizing.

They splash away from me—they’re their pod. People are alien.

I’m an unknown story, erasing myself with seawater.

There goes my honey and fog, my shoulders and legs.

* * *

What could be queerer than this queer tug-lust for what already is, who already am, but other of it?

Happens? That kind of desire anymore?

Oh I am that queer thing pulling and greener than the blue sea. I’m new with envy.

Beauty washing over itself. No reflection. No claim. Nothing to see.

If there’s anything bluer than the ocean it’s its greenness. It’s its turquoise blood, mixing me.

* * *

I was a woman alone in the sea.

Don’t tell anybody, I tell myself.

Don’t try to remember this. Don’t document it.

Remember: write down to not-document it.

If you’ve ever driven down Mystic Ave., you’ve seen the results of this fantastic summer employment program for teens

That combines hands-on environmental education with art.

Community brought together through youth participation in a decades-long mural project, creating a space ready for expression as well as opportunity, with local kids working on the mural as they are employed by the City of Somerville.

Additional Resources

Volunteer Match: A website that finds volunteer opportunities near you so you can help out your local communities.

Greatnonprofits.org: A website that finds nonprofits and organizations to donate to in your area

Footnotes

- John Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” in The Sociology of Community Connections, (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2011), 29-46.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- “Community (n.),” Online Etymology Dictionary, last modified October 13, 2021, https://www.etymonline.com/word/community.

- “Municipal (adj.),” Online Etymology Dictionary, last modified December 3, 2022, https://www.etymonline.com/word/community.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Phifer, Bryan M. “Community Development in America: A Brief History,” in Sociological Practice: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 4 (1990) Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/socprac/vol8/iss1/4

- Antebellum Slavery.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2956.html#:~:text=Enslaved%20African%20Americans%20also%20resisted,to%20keep%20their%20families%20together.

- Emmie Smit, Verna Nel, Lincoln Geraghty « Alienation, reception and participative spatial planning on marginalised campuses during transformational processes », Cogent Arts & Humanities, 2016/1.

- “Effective Altruism Is about Doing Good Better.” Effective Altruism, https://www.effectivealtruism.org/.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Bruhn, “Conceptions of Community: Past and Present,” 29-46.

- Malcolm X, “Message to the Grassroots,” Blackpast, August 15, 2020, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/speeches-african-american-history/1963-malcolm-x-message-grassroots/.

- Blackpast, “Message to the Grassroots.”

- Blackpast, “Message to the Grassroots.”

- Crooks and Andrews, “Community, Equity, Access: Core Geographic Concepts in Primary Health Care,” 270-73.

- Crooks and Andrews, “Community, Equity, Access: Core Geographic Concepts in Primary Health Care,” 270-73.

- Crooks and Andrews, “Community, Equity, Access: Core Geographic Concepts in Primary Health Care,” 270-73.

- Majee and Hoyt, “Cooperatives and Community Development: A Perspective on the Use of Cooperatives in Development,” 48-61.

- Kino, Carol. “Where Art Meets Trash and Transforms Life.” The New York Times, The New York Times, (21 Oct. 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/24/arts/design/24muniz.html.

- Cohen-Cruz, Jan. “An Introduction to Community Art and Activism.” (2014). https://library.upei.ca/sites/default/files/an_introduction_to_community_art_and_activism_cohen_cruz.pdf

- Force, Thessaly La, et al. “The 25 Most Influential Works of American Protest Art since World War II.” The New York Times, The New York Times, (15 Oct. 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/15/t-magazine/most-influential-protest-art.html.

- Weinik, Steve. “City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program: First 30 Years – Google Arts & Culture.” Google, Google,https://artsandculture.google.com/story/city-of-philadelphia-mural-arts-program-first-30-years-mural-arts/XAURcRmqHRAiJQ?hl=en.

- Lowe, Seana S. “Creating Community.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, Vol. 29 No 3. 3 June 2000. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/089124100129023945

References

“Antebellum Slavery.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2956.html#:~:text=Enslaved%20African%20Americans%20also%20resisted,to%20keep%20their%20families%20together.

Bruhn, John G. The Sociology of Community Connections. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1633-9.

Chang, Rachel. “7 Concrete Ways to Do Your Part for the Asian American Community Right Now.” Travel and Leisure, March 17, 2021. https://www.travelandleisure.com/travel-news/how-to-report-asian-hate-crimes-help-aapi-community.

Chaveepojnkamjorn, Wisit, Sureeporn Songroop, Pratana Satitvipawee, Supachai Pitikultang, and Suruchsawadee Thiengwiboonwong. “Effect of Low Birth Weight on Child Stunting among Adolescent Mothers.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 10, no. 11 (2022): 177–91. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2022.1011013.

Cohen-Cruz, Jan. “An Introduction to Community Art and Activism.” 2014. https://library.upei.ca/sites/default/files/an_introduction_to_community_art_and_activism_cohen_cruz.pdf

Crooks, Valorie A., and Gavin J. Andrews. “Community, Equity, Access: Core Geographic Concepts in Primary Health Care.” Primary Health Care Research & Development 10, no. 3 (2009): 270–73. doi:10.1017/S1463423609001133.

Deborah Lee. “Mystic River Mural Project Is an Impressive Ongoing Story.” 2 Sept. 2018. https://artoutdoorsdl.com/2018/08/31/mystic-river-mural-project-is-an-impressive-ongoing-story/

“Effective Altruism Is about Doing Good Better.” Effective Altruism, https://www.effectivealtruism.org/

Force, Thessaly La, et al. “The 25 Most Influential Works of American Protest Art since World War II.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 15 Oct. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/15/t-magazine/most-influential-protest-art.html.

History. “Malcolm X,” October 29, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/malcolm-x.

Kino, Carol. “Where Art Meets Trash and Transforms Life.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Oct. 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/24/arts/design/24muniz.html.

Lowe, Seana S. “Creating Community.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, Vol. 29 No 3. 3 June 2000. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/089124100129023945

Megan Garber. “What Does ‘Community’ Mean?” The Atlantic, July 3, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/07/what-does-community-mean/532518/.

Online Etymology Dictionary. “Community (n.),” October 13, 2021. https://www.etymonline.com/word/community.

Online Etymology Dictionary. “Municipal (Adj.),” December 3, 2022. https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=municipal.

Phifer, Bryan M. (1990) “Community Development in America: A Brief History,” Sociological Practice: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/socprac/vol8/iss1/4

“Residential Security Map of Boston, Mass.” Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:00000x52b

Shaughnessy, Brenda. “Identity & Community (There Is No ‘I’ in ‘Sea’).” Poets.org, 2019. https://poets.org/poem/identity-community-there-no-i-sea.

Weinik, Steve. “City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program: First 30 Years – Google Arts & Culture.” Google, Google, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/city-of-philadelphia-mural-arts-program-first-30-years-mural-arts/XAURcRmqHRAiJQ?hl=en.

Wilson Majee & Ann Hoyt (2011) Cooperatives and Community Development: A Perspective on the Use of Cooperatives in Development, Journal of Community Practice, 19:1, 48-61, DOI: 10.1080/10705422.2011.550260Youtube. “In a Land of Plenty, Faith and Farming Unite This Community | Short Film Showcase,” September 18, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Vzjwz0ZKho.

Contributors

Ruby Goodman

Katrina Lin

Isaac Leib