Introduction

Decolonial Love is the regaining of one’s autonomy within existing colonial frameworks through intimacies within platonic, romantic, or coalitional relationships. As Tuck & Yang explain, decolonization is not a metaphor but an actual physical practice. Therefore, as we explore various forms of decolonial love in order to gain a better understanding, we are paying close attention not to metaphors of the term, but rather examples of its physical practice. [1]

Before proceeding, it is important for us to define what we mean by love.

Love: For our definition of love, we turn to Adrienne Rich’s 1977 essay, “Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying.” Rich writes that using the word love signifies an honorable human relationship, one which she defines as “a process, delicate, violent, often terrifying to both persons involved, a process of refining the truths they can tell each other…It is important to do this because it breaks down human self-delusion and isolation.” [2] Rich’s definition seemed particularly relevant to us given her inclusion both of violence, which is present in much of the colonial spaces we investigate, and also isolation, which also came up many times in our research. Slightly tweaking her definition to work for our discussions, we define love as a process of intentional closeness between one or more humans, where care and truth are offered as a counter to violence, fear, and isolation.

Decolonial Love in Intimate Relationships

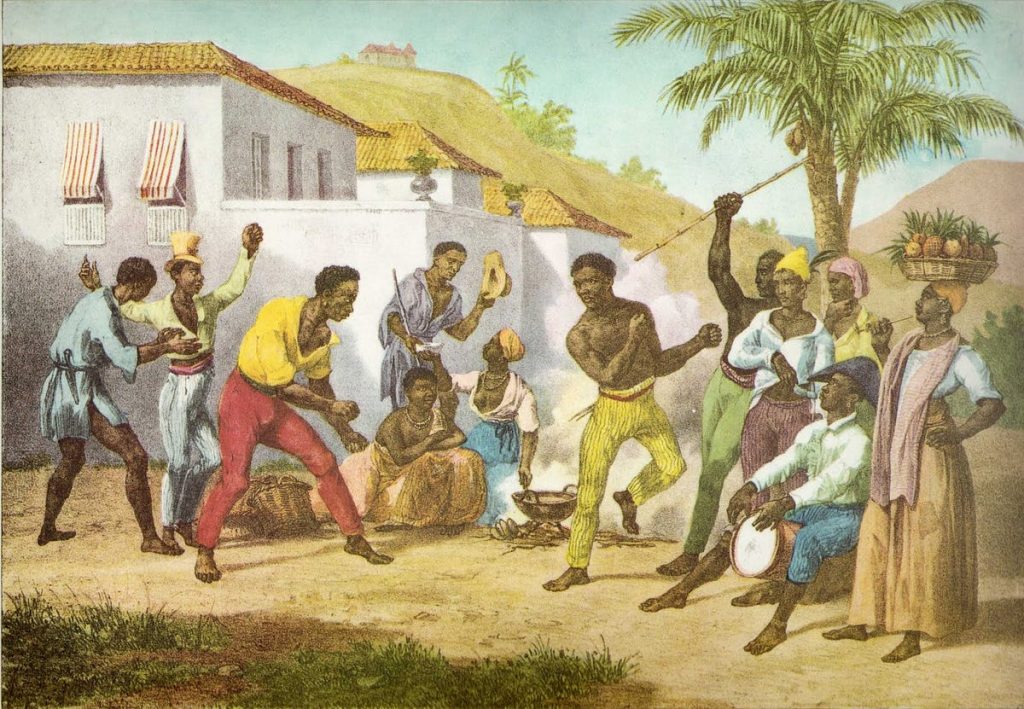

Decolonial love can exist within intimate relationships, whether they be familial or sexual; however, decolonial love is the physical defiance of colonial frameworks through relationships. One often assumes that decolonial love can exist in love that has been considered taboo, like interracial love; however, we argue that interracial love alone is not an example of decolonial love. While interracial love defies cultural frameworks propagated by racialization and eugenics, they have always existed in a way that encourages white superiority through colonial frameworks. For example, in the casta system, the Spanish empire categorized interracial love to ultimately propagate white supremacy throughout the empire.

(Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlán, Mexico)

Some present-day examples of how decolonial love is often depicted could be seen in the 2023 Netflix film You People. In the film, an interracial couple struggles to have a relationship as their family’s vastly different cultures and beliefs clash with one another. At the end of the film, both families were able to look past their differences and come together out of their love for their children.

The scene demonstrates how cultures coming together does not necessarily signify decolonial love. The parents in the scene were both victims of colonization and eugenics; however, both families compete for which group of people underwent the most trauma caused by colonialism to ultimately force accountability or instill a power dynamic. In other words, within these colonial constructs, minorities compete to receive validation for all they have suffered. Therefore, interraciality doesn’t always correlate to decolonial love because these forms of relationships carry power dynamics that are fostered or intensified within colonial frameworks, not outside of them.

Decolonial love is a kind of love that dismantles the internalized colonial structures, a love that exists outside or opposes these structures. The musical “In the Heights” by Lin Manuel Miranda demonstrates how interraciality could be a form of decolonial love. Benny is an African-American who is in love with Nina, a Latina. Since Benny is African-American, Nina’s father did not believe Benny was good enough for his daughter. Nina’s father carries antiblackness attributed to Latin America’s colonialism in its casta system.

(focus on 2:24 – 3:10)

Link to the lyrics

Although Nina’s father forbade Benny and Nina from being together, Nina and Benny form a relationship outside the colonial constructs ingrained in Nina’s culture. In loving outside these frameworks, Nina abandons colonial constructs associated with antiblackness to be with Benny.

Links to the lyrics

In “When the Sun Goes Down”, Nina and Benny come together even though they would be alone in their love, they would still have each other. In the lyrics, “So we’ve got this summer/And we’ve got each other/Perhaps even longer”, Nina and Benny against all else have their love for each other. The love between Nina and Benny highlights decolonial love as their relationship dismantles the previous colonial infrastructures that oppose their relationship. In comparison to You People, In the Heights demonstrates decolonial love through Nina and Benny as their relationship opposes colonial frameworks instead of working within them.

In Breath, Eyes, Memory, Edwidge Dandicat demonstrates how decolonial intimacies exist not only within romantic relationships but also exist within familial relationships. Throughout the novel, the two protagonists, Martine and Sophie, struggle to understand one another as Sophie defies the colonial constructs of chastity enforced upon her by her mother, Martine. In the novel, Martine’s mother, in Haiti, would insert her finger into her to ensure that her hymen was still intact. Martine’s mother would stop these examinations when Martine was raped by a man she did not know while she was out in the fields. From Martine’s rape, came Sophie. After Martine realizes that Sophie was seeing her neighbor, Joseph, Martine began to check on Sophie to ensure that her hymen was intact. To liberate herself from the sexual trauma inflicted by her mother, one night Sophie takes a pestle and inserts in herself to break her hymen. When she fails the test the next night, Martine kicks Sophie out and tells her to go see Joseph.

“”I did it”, she said, “because my mother had done it to me. I have no greater excuse. I realize standing here that the two greatest pains of my life are very much related. The one good thing about my being raped was that it made the testing stop. The testing and the rape. I live both every day.”

Breath, Eyes, Memory, Edwidge Dandicat, Chapter 26

Through Martine’s trauma, Sophie was forced to carry her mother’s shame of losing her virginity outside of marriage. However, Sophie breaks her own hymen so that may she escape these colonial frameworks of marriage and chastity forced upon her by her mother. In taking her own virginity, Sophie gains autonomy over her body and liberates herself from the sexual trauma she experiences through these colonial frameworks of forced chastity. Although Sophie does not have an intimate relationship with someone else, she still has this moment of intimacy with herself, a moment of intimacy that opposes colonial frameworks that oppressed her and gives her the agency to experience her own sexuality outside of them. In other words, Sophie taking her own virginity is a form of decolonial love because she opposes the dominant generational, oppressive constructs she is forced to live in. Therefore, decolonial love can exist within intimacies between romantic partners and between the self. Decolonial love can be any form of intimacy, both brief or everlasting, as long as it is a love that gives one the agency and autonomy to live in their own way.

In conclusion, decolonial love through intimate physical relationships could be presented in many forms. The throughline between these different forms of decolonial love is that all of them oppose colonial constructs in ways that give these individuals agency.

Decolonial Love in Coalitions

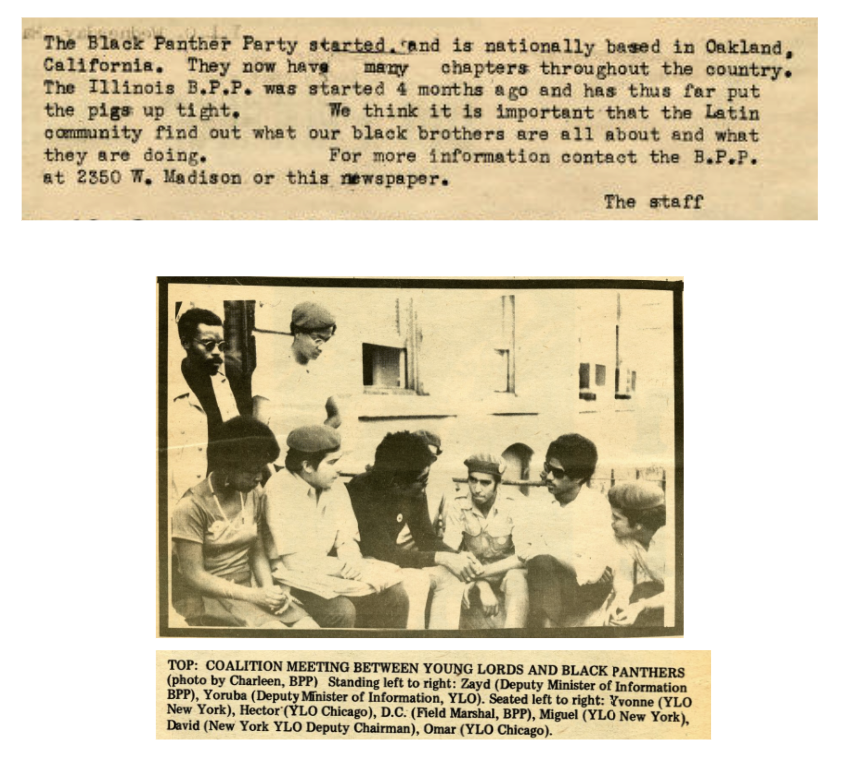

Showing love for one’s community often means working against forces that fracture and harm it, in order to care for community members’ basic needs and institute joy and peace. The Young Lords Organization (YLO), and the New York offshoot the Young Lords Party (YLP) [1], engaged in frequent coalitions and acts of solidarity with the Black Panthers (BPP) to this end.

The Young Lords Organization was founded in 1968 in Chicago by José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, growing from a street gang aiming to protect and serve the majority Puerto Rican community in Lincoln Park [2] to a widespread political organizing unit and movement working to liberate all colonized people. The YLO was modeled after the Black Panther Party and much of their projects were replications of BPP activisms [3]. The most well-known relationship between the YLO and the BPP was the Rainbow Coalition, an extraordinary example of coalitionary community organizing in which the YLO, the BPP, and the Young Patriots Organization (an organization of poor White Southerners from Uptown, Chicago) supported and learned from each other in working against police violence, poverty, and healthcare disparities. The Coalition was formed by Fred Hampton, the deputy chairman of the national Black Panther Party and chair of the Illinois chapter.

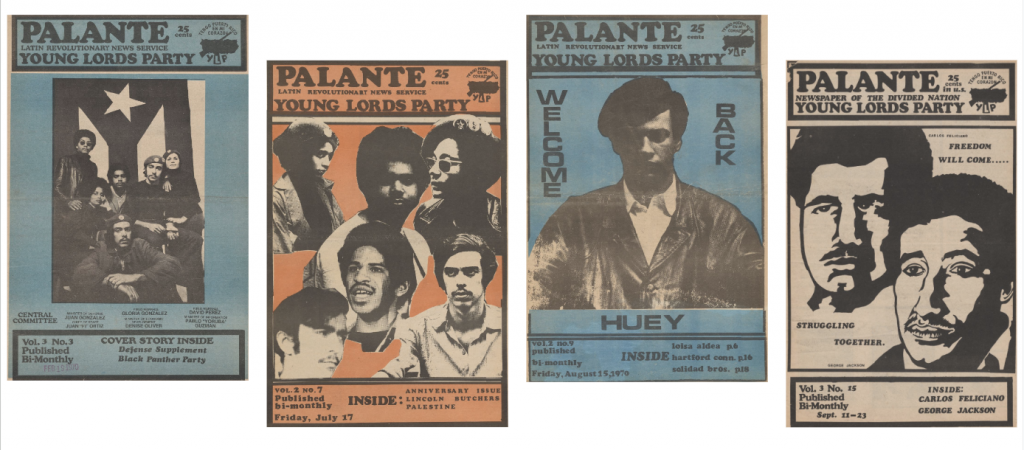

The YLP, YLO, and BPP all communicated to their base via print newspapers and all communications frequently reference Black and Puerto Rican solidarity. The three sources examined here are the YLP’s Palante (1970-1976), the BPP’S Black Panther (1967-80), and the YLO newspaper (1969-71 [4]). Throughout each publication, organizations utilize tactics to elucidate the love and care between Black and Latino communities to convince readers to care about the other group in the fight against colonialism and its myriad of trickle-down effects.

Left to right, published February 1971 [5], July 1970 [6], August 1970 [7], September 1971 [8]

“We realize that capitalism has used racism to keep oppressed people oppressed and divided from one another and fighting each other while the f****t pig makes the money. We must rid ourselves of the racist attitudes that exist among our Puerto Rican people. We must end the racist attitudes towards our Afro-American brothers and sisters. We grow up together, are victims of capitalism together, so we must pick up the gun and fight the racist, capitalistic pig together!”

Iris Morales Luciano, Ministry of Education of the Young Lords Party [9]

The above quote from Volume 2 Issue 7 of Palante (seen above, the second cover in orange) calls for an end to anti-Black racism and colorism in the Puerto Rican community. In emphasizing that Puerto Rican and Black children “grow up together” in New York City neighborhoods, Luciano emphasizes that Puerto Rican and Black children should be developing familial or kin-like relationships due to their shared environment and experiences however “each is taught that the other is inferior and to be avoided or hated,” driving them apart along racial lines. Luciano even highlights that dark-skinned Puerto Ricans “cling to being Puerto Rican in order to negate their blackness” and light-skinned Puerto Ricans “start viewing themselves as white…in order to avoid identification as Puerto Ricans.” Decolonial love, in this example, can be seen as mending these divides that prevent Puerto Rican communities and their “Afro-American brothers and sisters” from working in solidarity against the racist, capitalistic “Amerikkkan” society. With the leadership of José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, the Young Lords aimed to change this.

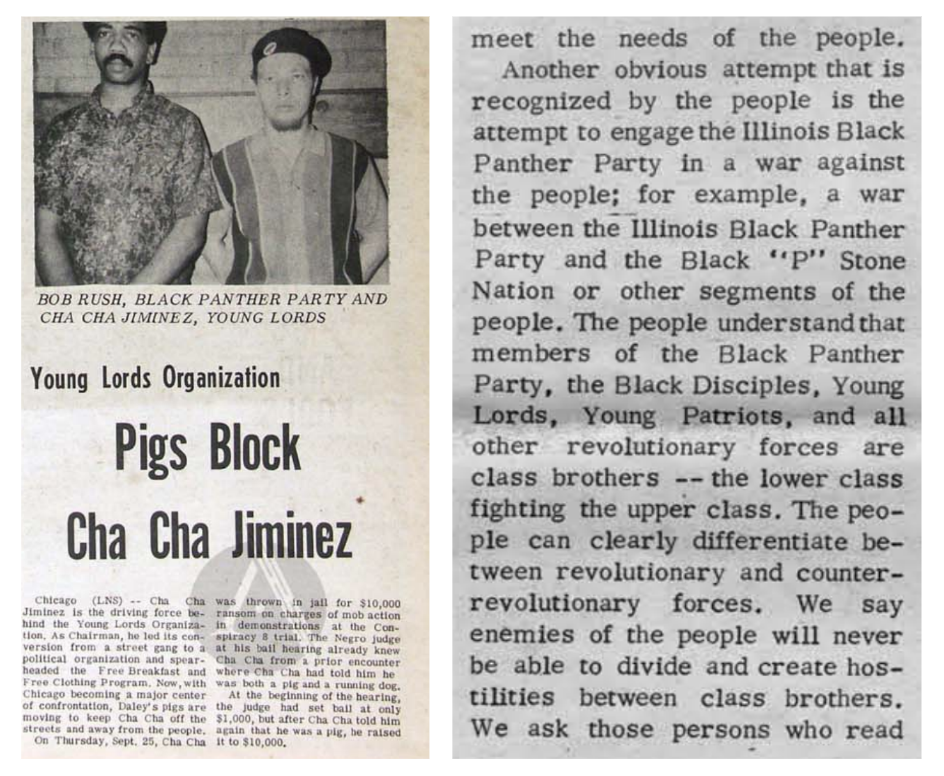

The above photo of the founders of the BPP Illinois chapter [12] and the Young Lords Organization as well as the article describing the Young Lords’s struggles with Chicago police garners empathy among Party members, calling attention to the shared enemies of the Young Lords and the Black Panthers: actors of state-sanctioned violence such as the police, the courts, and their judges. The Black Panthers reveal in the second excerpt that the state aims to pit “revolutionary forces” against each other to limit their power.

“The coalition worked because at every event that we had, we supported each other. There was no competition like there is today. And that competition really comes from COINTELPRO. If there was a demonstration every day it was like going to a party. Like hanging out. Like being a part of a family. If the Panthers have an event, there would be some Young Lords and some Young Patriots there and vice versa…We all knew about the class struggle…It was the people’s revolution. We can’t make a revolution without the people”

josé “Cha Cha” Jiménez, young lords founder [13]

COINTELPRO is the most well-known example of the government purposely attacking alliances between “revolutionary forces” such as the BPP and the YLO for the purpose of defunding and therefore disempowering such organizations working against the state and its actors. In fact, the Church Committee (otherwise known as the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations) found that J. Edgar Hoover specifically conducted attacks on the close relationship between the Black “P” Stone Rangers and the BPP [14], just as is written about in the Panther article five years before the information was made public. Clearly, despite the government’s attempts to keep attacks covert, the Panthers were very aware of attacks meant to segregate and isolate revolutionary groups from each other. Public commitments to solidarity in their newspapers and at events showed organizers’ strong bond and commitment to their own community as well as the community of their “class brothers.” Just as Jimenez describes the relationship between the YLO, BPP, and the Young Patriots as one resembling a “family,” the use of the term “class brothers” speaks to the close familial bond between class organizers. Like family, these prominent organizers supported each other and their demonstrations out of care for each other and care for their own communities, all of whom benefited immensely from the increased support and programming resulting from the coalition: best exemplified by the Young Patriots and YLO starting free breakfast programs, daycare centers, and health clinics in their own communities modeled after the BPP’s “Survival Programs” [15].

In the introduction to the reprint, Young Lords refer to the Black Panthers as “brothers” and highlight their shared goal of ending police violence (celebrating the BPP for “put[ting] the pigs uptight”) to argue why Puerto Rican readers should recognize and align with the plight of Black Panthers. The pictured quote and excerpt thus primarily highlight that the YLO aimed to garner respect and support from the Puerto Rican community toward their “black brothers.” The picture of a coalitionary meeting in and of itself is not indicative of any special type of relationship between the YLO and the BPP, however, the decision on the part of the YLO to publish the image is. Publishing a picture of the YLO and BPP getting along models supportive, respectful relationships between Black and Puerto Rican organizers and community members as well as respect and support between groups for each others’ mission as revolutionary forces.

“Fred used to say, ‘I am a revolutionary and I love all my people…Black people and Brown people and Red people and Yellow people.'”

DENISE OLIVER-VELEZ, first woman elected to Ylo Central committee and black panther party member [18]

Decolonial Love in Families and Friendships

Through our research, it became increasingly clear that it was not productive to separate familial love and friendship love when looking at the different aspects of decolonial love. Rather, given that close friendship often serves as an addition to or replacement of family, we have chosen to combine the two terms into one subsection of our term.

Specifically, in this section, we are investigating decolonial love in shipmate relationships and their legacies. Professor Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley explains in “Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic: Queer Imaginings of the Middle Passage,” that “in different parts of the Diaspora the relationship between people who came over to the “New” World on the same ship remained a peculiarity of this experience.” [1] These shipmate relationships were inherently decolonial, as they were one “way that fluid black bodies refused to accept that the liquidation of their social selves—the colonization of oceanic and body waters—meant the liquidation of their sentient selves.” [2] Tinsley describes this type of love, sexual or not, as queer in the sense that it illustrated “disruption to the violence of normative order…[by] loving your own kind when your kind was supposed to cease to exist, forging interpersonal connections that counteract imperial desires for Africans’ living deaths.” [3] Shipmates of the African Diaspora who were dehumanized and commodified in the transatlantic slave trade practiced decolonial love as they forged compassionate relationships with those around them in spite of their conditions of chattel slavery.

Tinsley notes that different regions of the Caribbean all have their own terms for “this special, non-biological bond between two people of the same sex.” [4] In Brazil, the term malungo is used, in Trinidad they use malongue, in Haiti the word is batiment, and in Surinam they use both sippi and mati. In the following subsections, we will investigate the use of these regional-specific terms for shipmates, connecting the historical meanings to usage today.

Malungo

The term malungo, “a Kimbundu word associated with ancestral symbols of authority carried by sea to establish a new hierarchy of lineages in a given territory,” was synonymous with “shipmate” for enslaved Africans in Brazil [5]. Two Brazilian pieces of art, a play and a song, offer more context on the role of decolonial love within malungo communities.

Zumbi dos Palmares Malungo (Zumbi of Palmares, the Malungo in English)

Zumbi dos Palmares Malungo is an unpublished and unedited three act play. It tells a story of “Afro-Brazilian memory and agency through the iconic maroon figure of Brazil, Zumbi, and his life in the maroon enclave of Palmares.” [6] Throughout the play, Zumbi is described as “highly reputed among the malungos of his faction” [7]. Zumbi loves the malungos as his own family, believes deeply in their fight for freedom, and even dies for the cause. In the face of colonization, the malungos practiced decolonial love through unconditional loyalty and support.

Saudação Malungo by Luedji Luna

Saudação Malungo was released by Afro-Brazilian singer Luedji Luna in 2017 on her debut album, Um Corpo no Mundo. Luna uses the term malungo to remind listeners of the colonial trauma that brought her Afro-Brazilian community to the country and persists in the anti-Black violence they experience to this day. In a Vanity Fair interview, Luna explains that in the face of the challenges of being a Black woman in Brazil, “in the end we have each other. We have the love of our daughters, of our mothers, of our friends, of our sisters. We are not alone.” [8] Luna’s music seamlessly demonstrates the tactic of decolonial love that she and her ancestors have clung to for generations.

Mati

Tinsley explains the lasting legacy of the Surinamese word mati, a word Creole women use for their female lovers. She notes that “figuratively mi mati is ‘my girl,’ but literally, it means mate, as in shipmate—she who survived the Middle Passage with me.” [9] She describes the inherently decolonial nature of this term, as “captive African women created erotic bonds with other women in the sex-segregated holds… In so doing, they resisted the commodification of their bought and sold bodies by feeling and feeling for their co-occupants on these ships.” [10]

“Mi Mati Wefie” is a song by Surinamese singer Lieve Hugo on his 1978 album Mi Lobi Van. It demonstrates the continuity of mati as a term of loving friendship in the Black Surinamese community.

Jahaji Bhai

Jahaji Bhai, translated to mean brotherhood of the boat, was written in 1996 by Brother Marvin to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the arrival of Indians in Trinidad. In the song, Brother Marvin highlights the “privilege” of their shared, mixed ancestry and emphasizes that the path forward is by coming together as one proud community of love. [11]

Connections to Decolonial Feminism

Considering the jahaji-behin, translated to sisters of the boat, and meaning the Indian women taken to the Caribbean in the early nineteenth century, Mehta argues that the women “mapped their ‘transoceanic’ (Bragard 2008) passages in acts of de-colonial resistance to invisibility, social marginality, and coercion by charting the maternal routes of indenture.” [12] I would like to extend this argument to include all of the women engaged in these lasting shipmate relationships, whether coming from India or the African continent.

“What began as a reaction to the racism of white feminists soon became a positive affirmation of the commitment of women of color to our own feminism. Mere words on a page began to transform themselves into a living identity in our guts”

Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, This Bridge Called my Back (1981)

Decolonial feminism is a form of feminism that exists outside the colonial frameworks of binaries. Decolonial feminism is the self-defining exploration of feminity in all forms and constructs, and most importantly, it is the invitation of others to live and define themselves outside of these constructs that are not applicable to them. Decolonial feminism in itself is another form of coalition building through the creation of familial and intimate relations. Sylvia Rivera, the founder of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (S.T.A.R), in her speech “Y’all Better Quiet Down” at the Gay Pride Rally (1973) in New York City, Rivera criticizes the exclusion of transgender people in the gay community. However, in her criticisms also exists a form of care, an invitation to those that live within binaries or constructs that limit their identity.

In her speech, Rivera says, “I do not believe in revolution, but you all do. I believe in the Gay Power.” Gay power is the power of care and advocacy for all, regardless of race, sexuality, or gender- it is the right for everyone to live in their identity. Although the crowd heckles her, Rivera extends an invitation to those that are isolated within colonial constructs or those who fight for life outside these constructs to join her outside these frameworks, to know that there are possibilities for care, family, and love outside of these frameworks. Therefore, decolonial feminism as exemplified by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua is not solely an opposition to white colonial feminism, but instead is a celebration of our own feminism.

Contributors

Ashley Batista, Kayla Drazen, Abigail Elsbree

References

Introduction Sources

- Tuck, Eve and Yang, K. Wayne. “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society 1, 1 (2012): 1-40, https://clas.osu.edu/sites/clas.osu.edu/files/Tuck%20and%20Yang%202012%20Decolonization%20is%20not%20a%20metaphor.pdf.

- Rich, Adrienne. “Women and Honor: Some Notes About Lying,” Motheroot Press, 1977, http://www.oregoncampuscompact.org/uploads/1/3/0/4/13042698/women_and_honor_-_some_notes_on_lying__adrienne_rich_.pdf.

Relationship/Intimacies Sources:

- Danticat, E. (2010). Breath, Eyes, Memory. Abacus.

- HBO. (2021). In The Heights. United States.

- Netflix. (2023). You People. YouTube. United States. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0MgsY1XU_hk.

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, April 29). Casta. Wikipedia. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casta#/media/File:Casta_painting_all.jpg.

- Youtube. (2019). In The Heights. The Club. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h9ae1DMFcNk.

Family and Friendships Sources:

- Tinsley, Omise’eke Natasha. “Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic: Queer Imaginings of the Middle Massage,” GLQ 14, 2-3(2008):198, doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2007-030.

- Ibid, 199.

- Ibid, 199.

- Ibid, 198.

- Sweet, James H. “Defying Social Death: The Multiple Configurations of African Slave Family in the Atlantic World,” The William and Mary Quarterly 70, 2 (2013): 271, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.5309/willmaryquar.70.2.0251.pdf.

- Kabir, Ananya Jahanara & Negro, Francesca. “Zumbi of Palmares, the Malungo,” Brasiliana: Journal for Brazilian Studies 8, 1-2 (2019): 343, https://tidsskrift.dk/bras/article/view/118027/166073.

- Ibid, 360.

- Ngangura, Tarisai. “Luedji Luna Wants to Complicate the Way We Talk About Love,” Vanity Fair, October 23, 2020, https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2020/10/luedji-luna-interview.

- Tinsley, 192.

- Tinsley, 192.

- Redock, Rhoda. “Jahaji Bhai: The emergence of a Dougla poetics in Trinidad and Tobago,” Identities 5, 4 (1999): 600, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1070289X.1999.9962630.

Coalition Sources:

- Organización Obrera Revolucionaria Puertorriqueña. (1969) Pa’Lante. Bronx, N.Y. https://dlib.nyu.edu/palante/about/

- “1968: The Young Lord’s Organization/Party” A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States. Library of Congress. https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/young-lords-organization

- Gonzales, Michael. “Latin Liberation News Service: The Newspapers of the Young Lords Organization” Marxists Internet History Archive (2013) 1-37. https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/ncm-1/ylo-papers.pdf

- Young Lords Newspaper Collection. DePaul University Library. Chicago, IL. https://digicol.lib.depaul.edu/digital/collection/younglords

- Palante. (Bronx, NY) February, 1971. http://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/cjsxm0g2

- Palante. (Bronx, NY) July 17, 1970. http://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/280gbcfp

- Palante. (Bronx, NY) August 15, 1970. http://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/stqjq898

- Palante. (Bronx, NY) September 11-23, 1971. http://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/tmpg4n3d

- Luciano, Iris Morales.“Racismo Borinqueño” Palante, July 17, 1970, http://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/280gbcfp

- Young Lords Organization. “Pigs Block Cha Cha Jiminez” Black Panther, October 18, 1969. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/black-panther/03n26-oct%2018%201969.pdf

- Black Panther Party. “Press Release: Illinois Black Panther Party” Black Panther, April 27, 1969. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/black-panther/03n01-apr%2027%201969.pdf

- “The Honorable Bobby Rush.” The History Makers. https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/honorable-bobby-rush

- Jimenez, José “Cha Cha.” “Rainbow Coalition Panel, October 23rd, 2016 (Oakland California Museum).” Grand Valley State University, 2016, https://digitalcollections.library.gvsu.edu/document/24640

- Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations. “Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” S. Doc. (Apr. 26, 1976). https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/94755_II.pdf

- Serrato, Jacqueline. “Fifty Years of Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition” South Side Weekly, September 27, 2019. https://southsideweekly.com/fifty-years-fred-hampton-rainbow-coalition-young-lords-black-panthers/

- YLO Staff. “October 1966 Black Panther Party Platform and Program” Young Lords Organization, March 19, 1969. https://digicol.lib.depaul.edu/digital/collection/younglords

- Ministry of Information. “New York Y.L.O.” Young Lords Organization, October 10, 1969. https://digicol.lib.depaul.edu/digital/collection/younglords

- Oliver-Velez, Denise. “Radicals in Black and Brown: Palante, People’s Power and Common Cause in the Black Panthers and the Young Lords,” UNC Chapel Hill Stone Center, 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cmDd9QVNNg&t=1465s.

Decolonial Feminism Sources

- Moraga, Cherríe, and Gloria Anzaldúa . This Bridge Called My Back. Watertown, MA: Persephone Press, 1981.

- Mehta, Brinda. “Jahaji-bahin feminism: a de-colonial IndoCaribbean consciousness,” South Asian Diaspora 12, 2 (2020): 180, https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.library.tufts.edu/doi/pdf/10.1080/19438192.2020.1765072?needAccess=true.

- “Sylvia Rivera, ‘Y’all Better Quiet Down’ Original Authorized Video, 1973 Gay Pride Rally NYC.” YouTube. YouTube, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mprUOGBWCvY.