Education

Definition

Education can be most simply defined as the transfer of knowledge, however we believe that the crux of the issues surrounding education lie with the knowledge that is being passed and the intent of the educator. Throughout this exploration of the keyword education, we navigate the different ways in which education has varied within and based on different identity groups. Through the lenses of just Queer Americans, African Americans, and Indigenous Americans, the disparity within education and its monumental impacts on these groups is clear. Each of these groups has navigated vastly different experiences within formal and community education. However, the commonality between these experiences is the diversity itself in education. While only three lenses were chosen due to time and scope limitations, we believe that the further exploration of education within different groups will only add to the complexity of the keyword education.

History of Public Education in the U.S.

“The older history textbooks were like syringes that injected the toxin of white supremacy into the mind of many generations of Americans.” – Donald Yacovone

The harvard gazette

Historically, the American public education system has marginalized African Americans, Indigenous peoples, and queer individuals, consistently focusing curriculums around white experiences and perspectives. These curriculums have led to the exclusion and misrepresentation of marginalized communities’ histories and contributions. For example, old history textbooks have been criticized for talking about slavery in ways that promote sympathy towards white Americans, as well as using “derogatory” language when speaking about African Americans. It was not until the mid-60s until the attitude towards slavery changed in textbooks in the United States (1). Public education in the United States was reinforcing the positive impacts of slavery through textbooks until the 1960s.

Indigenous people endured policies enforcing assimilation through schools designed to erase their cultural identities. Public education marginalizes Indigenous perspectives, as only Washington and Montana have integrated Indigenous curriculum statewide (2). To address equity, the U.S. education system should foster coexistence between these knowledge systems by incorporating storytelling and dialogue-based learning. The erasure of Indigenous perspectives in education has contributed to a lack of understanding and acknowledgment of their histories and contributions (2).

Queer students have also been excluded within the education system due to a structure centered around heteronormative values. Historical and current practices, like omitting LGBTQ+ histories from curriculum and enforcing discriminatory policies, have marginalized queer youth (3). The lack of representation and acknowledgment of queer identities in educational textbooks and programs continues the stigma and is detrimental to the development of inclusive environments.

These patterns demonstrate how the American education system upholds white supremacy and excludes diverse narratives, creating lasting inequities that continue to impact society today. Addressing these issues necessitates a reevaluation of curriculums and policies to make sure they reflect the diverse histories and experiences that constitute the fabric of the United States.

Indigenous Peoples in America

Education viewed within the context of Indigenous Americans exemplifies the extent to which the definition of education is dependent on the content taught. Within Indigenous communities, a unique aspect of education is the perspective of ways of knowing. Indigenous ways of knowing center empirical knowledge as equivalent to and in harmony with traditional beliefs and practices. Evidence gained through scientific experimentation is understood to be no more important than the traditional knowledge passed down through generation, and the experience each individual gains through simply being. Traditional knowledge is defined by Abenaki scholar Margret Bruchac as “a network of knowledges, beliefs, and traditions intended to preserve, communicate, and contextualize Indigenous relationships with culture and landscape over time” (4). It prioritizes understanding how to interact with humans, non-humans, and landscapes. This embodied knowledge is passed down both formally and informally- from one generation to the next through performances, storytelling, art, and even daily life. Factual data, religious concepts, and traditional practices are all taught in harmony with one another, rather than being inherently contradictory (4). These types of knowledge aren’t necessarily static either, but change based on time, place, and who it is taught to and by. Thus, Indigenous ways of knowing provide a definition of education that emphasizes tradition and culture rather than empirical facts.

The teaching of Indigenous people within boarding schools provides a stark contrast.

Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act in 1819, many schools were established to violently assimilate Indigenous Americans into white American culture. Working in concert with many Christian churches, these schools implemented a form of “cultural genocide… to accomplish the systematic destruction of Native cultures and communities”(6). Most simply the aim of this type of education was to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children were enrolled in these schools where they were taught not to speak Native languages and not to behave or present themselves in any way that might be perceived as Native and to replace those aspects of their identity with mainstream white American culture. These children were often forced to cut their hair, change their names, and spend months away from their families. At these schools they were often taught academic subjects, like math and science, along with trades, like agriculture and carpentry. This education focused on completely eradicating any sense of Indigenous identity or culture and replacing it with whiteness. The harmony of varied knowledge sources and experiential learning of traditional knowledge was entirely eradicated in favor of a strict education system of the one acceptable archetype. Thus, the definition of education, even within the historical context of Indigenous American experiences with education, is deeply dependent on its goals and the knowledge being taught.

African Americans

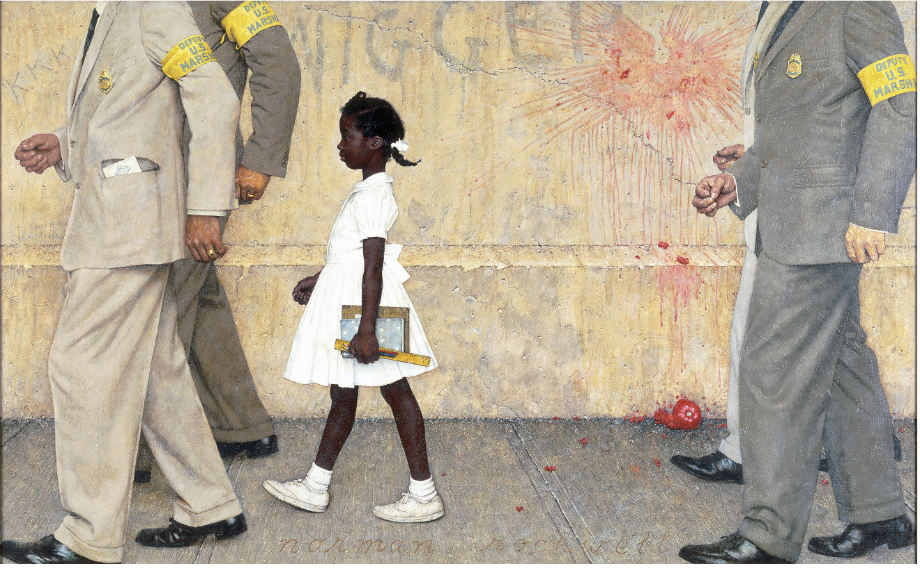

The oil painting, called The Problem We All Live With, was made in 1963 by Norman Rockwell, and it illustrates Ruby Bridges’ experience at William Franz Elementary School in New Orleans on her first day of school in 1960. When she went into school, the classroom was empty because the white parents took their children out of school to avoid having to sit near, and learn with, a black student (7). This oil painting is an example of the racist history of the American education system, and represents the verbal, emotional and physical abuse black children and families had to endure during the Civil Rights Movement. Born in 1954, the same year the Supreme Court decided school segregation to be unconstitutional, Ruby Bridges and other young African Americans were still barred from equal education opportunities as some schools didn’t comply with the Court’s decision (7).

The racist graffiti on the wall, the yellow armbands on the white men with Ruby, and the squashed tomato that was thrown towards the six-year-old are examples of the unfair behavior African Americans had to endure in the American school system. The yellow armbands indicate that the men walking are federal marshals, escorting Ruby into school. This oil painting provides evidence for the racist, injustice history of the American education system even after the Supreme Court’s decision to declare segregation as unconstitutional (7). There’s a history of inequality in formal education, and that inequality persists until we learn, understand, and create change in society today.

Racism is still present in the American education system today, as states ban Black history and other important lessons from America’s past. Government education bans prohibit future generations from learning about the country’s faults in order to help move us forward in the future (7). It’s necessary for everyone to be aware of the racist, uncomfortable history that continues to affect the United States education system today; so we’re able to understand biases and privileges certain groups of people have.

The creation of Freedom Schools in Mississippi during the 1964 Freedom Summer was a significant educational advancement as a result of backlash to the discrimination Black people experienced (8). The purpose of these schools was to challenge the oppressive systems of the day and empower Black children. The curriculum offered what conventional, segregated public education had consistently denied: an emphasis on Black history, civic engagement, and critical thinking. Freedom Schools were centers of social and political awakening that went beyond conventional educational objectives. Pupils were urged to consider the potential for freedom and equity as well as to critically examine societal inequalities. Lessons that addressed community organizing, voter registration drives, and the larger connection between education and social change were frequently tied to activism (8).

Freedom Schools thus personified the notion that education play a pivotal role in bringing about social change. This tradition is carried on by programs like the Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools, which provide learning environments that value cultural identity and promote community involvement. Despite these initiatives, institutional and historical racism continue to influence the educational system. School financing, the school-to-prison pipeline, and curricular content disputes are just a few of the ongoing issues facing our educational system (8). The Freedom Schools serve as a reminder of how education motivates people to resist and take charge of their lives.

Queer Americans

Disclaimer

The authors want first to note that the term “queer” is what Garden State Equality calls a “yellow light word” [9]. Some people use the term to self-identify while others associate it with harm (see “Queerness”). In this essay, we use “queer” in the spirit of honoring those who actively work to reclaim the term as a form of empowerment for LGBTQ+ communities. Similarly, we want to note that when using the acronym “LGBTQ+,” we are referring to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, and all other non-cisgender or non-heterosexual individuals. Each individual has the right to identify or not identify with a term.

Foundations of Queer Culture and How it Educates

Organizations at the beginning of the Gay Liberation movement in the 1950s like the Mattachine Society represent a new form of community for 20th-century queer communities, building on and benefitting from the cultural trends of the Harlem Renaissance to facilitate political activism. The Harlem Renaissance was a flourishing of Black and queer culture in the 1920s and serves as the foundation for queer culture and its inherent educating of LGBTQ+ folx.

During Harlem Renaissance, Black and queer people founded spaces like the Ubangi Club in New York City where they freely expressed identity through fashion, music, and art [10]. Without public spaces to be openly queer or safely Black in a time of Jim Crow even in the northern United States, Black and queer communities relied on secretive spaces, often speakeasies, to come together for recreation. Through these underground spaces, people developed a system of self-education, not only learning from each other, but building the curriculum for queer culture that remains a foundation today.

This principle of self-education through community-building due to a lack of formal education on a topic fits any marginalized group or subgroup, including transgender communities and immigrants.

Racism Within Queer Communities

Just because queer people are a minority does not exempt them from abuse towards other minorities. Within queer communities, racism is a prevalent force that often alienates people who hold both queer and non-white racial identities from mainstream queer spaces despite queer culture’s origins in the Harlem Renaissance. 20th-century author and activist James Baldwin documents such alienation in his novels Giovanni’s Room and Another Country, drawing on his own experiences as a queer Black man at the height of the Civil Rights movement. In Black sociopolitical circles, people were hesitant, or often fully resistant to, accept the goals of the Gay Liberation movement. Conversely, white gays and lesbians bought into systemic racism ideology and blocked queer BIPOC people from organizations like the Mattachine Society [11]. Black queer people like Baldwin were thus left to their own devices when educating themselves about identity in a positive light. Baldwin’s experience illustrates the most common mode: writing your own narrative. Through his novels, Baldwin educated himself on identity through self-reflection, a practice that continues to be used by Black queer folx today.

Beyond Formal Learning in Schools

Education isn’t always positive. According to scholars Cory J. Cascalheira and Na-Yeun Choi [12], education can be used as a mode of control or dehumanization of a group. Learning happens not just through what a school or teacher provides, but what it doesn’t provide. Studies show that schools without queer-inclusive curriculum, Gender and Sexuality Alliance clubs, supportive faculty, and affirming policies and facilities yield poor mental health among queer students [13]. A lack of support in such ways teaches by omission the devaluation of queer, particularly transgender, identities, forcing students to hide and feel ashamed of their identities. In other words, when transgender students are, for example, denied access to a bathroom that matches their gender identity, they are subjected to feelings of worthlessness by the denying institution and thus taught that they do not belong in a given space.

GLSEN’s 2021 National School Climate Survey details how anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ+ policies affect learning environments

Education Today

Education, no matter its format or manifestation, persists in all walks of life. Today, while the on-book barriers of Jim Crow or forcible removable of Indigenous children from their families are no longer officially in place, discrimination in the classroom remains very much alive. In 2023, the US Supreme Court ruled affirmative action unconstitutional in Fair Admissions v. Harvard, while Florida’s Parental Rights in Education law bans LGBTQ+ topics in curricula, illustrating the present continuity in disagreement over the type of education students should receive. Remains of Indigenous children at former school sites are still being found in Canada and the US, opening wounds and conversations on how to address education on a marginalized group for the majority. This “education about ‘us’ for ‘them’” concept continues to be a debate among policymakers and education scholars. A seeming continuity in American history, education remains a controversial topic.

Supplementary Materials

References

1. Yacovone, Donald, and Liz Mineo. “How Textbooks Taught White Supremacy.” The Harvard Gazette, 4 Sept. 2020.

2. Huff, Leah. “Through a White Colonial Lens: A Look into the US Education System.” School of Marine and Environmental Affairs, 28 Feb. 2022, smea.uw.edu/currents/through-a-white-colonial-lens-a-look-into-the-us-education-system/

3. Rafei, Leila. “How LGBTQ Voices Are Being Erased in Classrooms: ACLU.” American Civil Liberties Union, 24 Feb. 2023, www.aclu.org/news/lgbtq-rights/how-lgbtq-voices-are-being-erased-in-classrooms-censorship

4. Bruchac, Margaret M. 2014. “Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Knowledge.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Claire Smith, ed., chapter 10, pp. 3814-3824. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media.

5. “1819-2013: A History of American Indian Education.” Education Week, 4 Sept. 2019, www.edweek.org/leadership/1819-2013-a-history-of-american-indian-education/2013/12.

6. “US Indian Boarding School History.” The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, boardingschoolhealing.org/education/us-indian-boarding-school-history/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2024.

7. “Norman Rockwell + the Problem We All Live With.” The Kennedy Center, www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media-and-interactives/media/visual-arts/norman-rockwell–the-problem-we-all-live-with/

8. Perlstein, Daniel. “Teaching Freedom: SNCC and the Creation of the Mississippi Freedom Schools.” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, 1990, pp. 297–324. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/368691

9. Saliski, Justine Evyn, Bailey E. Asbury, Andrew Perez, and Zach Conroy. “LGBTQ+ History and Inclusive Curriculum.” Garden State Equality Youth-Led Webinars. Lecture presented at the Garden State Equality Youth Advisory Board’s LGBTQ+ History and Inclusive Curriculum Webinar, April 11, 2024.

10. Kirschke, A. H. (Ed.). (2014). Women artists of the Harlem Renaissance. University Press of Mississippi.

11. Chevat, Richie, and Michael Bronski. A queer history of the United States for young people. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 2019.

12. Cascalheira, Cory J, and Na-Yeun Choi. “Transgender Dehumanization and Mental Health: Microaggressions, Sexual Objectification, and Shame.” The Counseling psychologist, May 1, 2023. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10118059/.

13. Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., & Menard, L. (2022). The 2021 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of LGBTQ+ youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN.

Contributors

Benjamin Pensky

Ananya Suryadevara