Definition

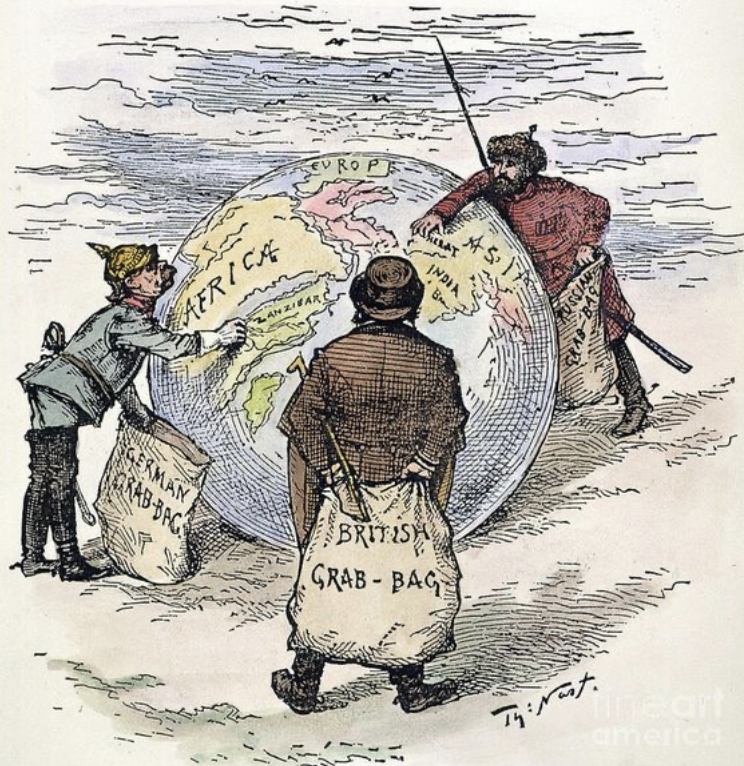

Imperialism is a political strategy, state policy, or practice when territorial acquisition is employed to extend power as well as political and economic control over other areas. Oftentimes, imperialism consists of the use of economic and military power with the aim of collective or individual domination [1].

Discussion

According to Robert Young, the term “imperialism” is utilized to describe one’s domination and influence upon another group. Imperialism operates from the center, it is a state policy, which is developed for financial and ideological reasons [2]. This signifies that imperialism is not just about invasion. In fact, it does not always have colonies, but could be done just to spread influence. From this perspective, imperialism is a much broader term due to it relating to domination and influence, which could be conducted through culture, ideology, military, diplomacy, not just through invasion.

Writing in 1999, Simon Ortiz opened his collection of poetry, “from Sand Creek” by stating that, “At this point in history, Indians are still not accepted as full participants in and members of world human cultural society.” Ortiz continues his introduction unapologetically: “If [Indians] choose to, they can accept that severely restricted role, but then they will have to tolerate that role’s social, political, and cultural limitations.” [3] Here, Ortiz identifies American colonization’s attempt to erase and displace expansive Indigenous societies, culture, knowledge, and identities to be constricted within European standards. Hungry for profit, the American empire was built through the seizing of land and labor, and achieved through conquest. Now, the United States stands a global power among the empires of the world, continuing to bloat through its voracious globalization. Imperialism creates profit and control through cultural and ideological domination, specifically the homogenizing imposition of race, gender-binary, heteropatriarchy, language, and capitalism.

The US federal government utilizes racial-settler capitalism for the production of profit and enforcement of identity achieved through violent land seizure and the centralization of European culture. By 1885, the Indian Wars had stolen and reduced the land of hundreds of Indigenous tribes; In the North-East, the Lakota had been relocated to the Great Sioux Reservation, where they maintained “self-conceptions and social relations… [operating] outside of normative US forms of individualism.” [4] This rejection included independent conceptions of gender—such as the historied celebration of non-binary and transgender peoples—which stemmed from the community, land, dreams, and the understanding that the “physical aspects of a thing or person… are not nearly as important as its spirit.” [5] These non-European conceptions of identity thwarted US attempts at subjugation and colonization, inhibiting their production of labor for the profit of the US. In response, the federal government turned to ways to dictate identity; aiming to “[enforce] new ways of knowing oneself and others… to produce… ‘bureaucratically knowable and recordable individuals’ whose self-interest could be predicted and manipulated by officials.” [6] This constriction was conducted through off-reservation residential schools which sought to create the individual motivation to labor and impose euro-centric identity. In doing so, the federal government worked to dissolve Indigenous sovereignty and culture while expanding a compliant working class. In 1999—the same year and “point in history” as Ortiz wrote—Shannon County, South Dakota, the home of the Pine Ridge Reservation of the Oglala Lakota, was named the poorest place within the country. [7] From colonially seized foundations and now to globalized exploitation, the United States’ remains intertwined with imperialist practices, exemplifying the danger and power of empire.

Race is a capitalist invention which creates the political, social, and economic inequalities necessitated by capitalism, and which has developed inextricably with gender, class, and sexuality. Following the popular growth of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, the false narrative of race as a biological trait was repeated and cemented through fallacious science. Race difference as an ideology is utilized to create a “framework of perception” which defines social power inequalities and generalizes identity. [8] Examining racial construction with greater intersectional awareness elucidates race to be “fundamentally inseparable from the gendered, sexualized, and classed contexts in which ideas of race and racial categories develop.” [9] The development of race occurs in colonizing process; alongside race, gender and heterosexuality are imposed on colonized subjects as a form of domination, making these categories of identity “interlocking and mutually constitutive.” [10] Through these constrictions, empires create hierarchies of identity and power used to exploit, control, and separate; under capitalism, social categories such as race and gender are used to “1) divide workers 2) structure labor 3) shift blame [and] 4) manage and hide unemployment.” [11] In the formation of the European feudal system, race was created to separate the laborers from those who owned the means of production based on biological difference—but not necessarily skin color. As race has come to define relationships of labor, capitalism and race have developed together so as to be essential in their co-maintenance. In the US empire, race has been developed to divide the working class, to separate people into “levels of exploitation,” divert blame from the ruling class, and naturalize racialized incarceration for the creation of a reserve labor force. [12] Imperialist empires’ use of racial capitalism as a tool for division, control, and the production of profit has spread the construction of race throughout the globe, ultimately enforcing euro-centric oppression and exploitation.

Erasure of language works to suppress pre-imperial knowledge; currently, global Englishization is being used to produce profit through identity-regulation. The work of preserving and awakening languages defies the colonially attempted murder of—often indigenous—identity, culture, history, and knowledge. Accessing these languages means the continuation and active evolution of cultural identities and worldviews embedded within the language. Hundreds of indigenous societies have terms, roles, and respect for those who live outside of the Western gender binary and outside of LGBTQ conceptions of gender construction. Before colonizing-exposure, the language of the Zapotec peoples of Southern Mexico did not include gender and had no terms to make distinction between man and woman. In active resistance to constricting colonial pressures, the Zapotec peoples of Juchitán use the term muxe to identify “people who are biologically male but embody a third gender that is neither male nor female, and who refuse to be translated as transvestite.” [13] The muxe identity has been most closely compared to queer understandings of gender fluidity. Through imposition of language, European empires have narrowed identity and culture to western standards which facilitate control. Globally, capitalism works alongside Englishization to regulate identity in service of international trade and collaboration. International companies impose Englishization through “normalization and surveillance,” in order to “[transform] local selves in ways deemed suited to the aim of international competitiveness.” [14] With the ultimate goal of profit production, language has been utilized as another tool to create exploitable homogeneity and redefine local cultures as outsiders to the global euro-central standard.

Simon J. Ortiz’s collection of poems, “from Sand Creek” is inspired by the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, in which hundreds of Arapaho and Cheyenne peoples were murdered by the US military while in the midst of negotiations for peace with the government and military of Colorado. Throughout the collection, Ortiz explores how imperialism has been embedded within the American identity, from the genocide and displacement of Indigenous peoples to American intervention in the Vietnam War. In the 34th untitled poem in the collection, Ortiz brings Native erasure and assimilation into direct focus:

Pain and death did not have to be propagated as darkness and wrong and coldness; they could have listened and listened and learned to sing in Arapaho.

Somehow

it was impossible

for them

to understand true safety.

Knowledge for them

was impossible

to understand as pain.

That was untrustworthy,

lost to memory.

Death was sin.

Their children

hunkered down, frightened

into quilts, listening

to wind

speaking Arapaho words

for pain and beauty and generations.

But they refused to understand.

Instead, they protested

the northwind,

kept adding rooms.

Built fences.

Their children learned to plan.

Their parents required submission.

Warriors could have passed

into their young blood.

Imperialism often relies on the physical suppression of Indigenous people by an invading force. Through state-sanctioned violence, the ruling class maintains power. It relies on laws that criminalize poverty to keep imperial powers in charge. This physical manifestation of imperialism can be seen in the borders that split up Palestine in an attempt to separate people who would otherwise unify as one nation. Imperial borders are used to separate different people across the Arab world who would otherwise live without rigid divisions. In Palestine: A Socialist Introduction, Sumaya Awad and Annie Levin write that “prior to [the Balfour Declaration and Sykes-Picot Agreement] borders differentiating Syria from Lebanon and the East and West banks of the Jordan River were porous” [15]. Today, these borders, drawn by international imperial powers, remain as a reminder of the imperial influence in the physical shaping of countries. In the United States, borders are used to restrict movement and keep poor people and people of color from freely moving between states and countries. At the border between the US and Mexico, armed guards attack people of color presumed to be “illegal” immigrants to protect the whiteness of the imperial state.

Internally, brutal police forces roam neighborhoods of color and poor neighborhoods in order to maintain hierarchies of white supremacy and lock up people who challenge the capitalist status quo. Another way imperialism manifests itself through policing is the attacks on unhoused people sleeping in the streets and through laws that make it illegal to “loiter” but do not provide alternative shelters. In Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, Cedric Robinson writes how “characteristically, capitalist imperialism had magnified the capacity for capital accumulation by force variously disguised as state nationalism, benevolent colonialism, race destiny, or the civilizing mission” [16]. Imperialism relies on these forms of racial domination to justify the hierarchies it imposes. Through criminalizing people of color and making up borders that serve western capitalist interests, imperialism implies that it is the right of the imperial powers to dominate and attack Indigenous people and enforce laws that protect themselves.

One of the modern-day empires is Russia, which was previously the Russian Empire and the leading nation of the Soviet Union. In the US, imperialism was justified as building civilization for other nations and races [17]. It was similar in the Soviet Union. Between the years of 1928-37, there was a process of “proletarianization” in Central Asia as there was no organized urban proletariat. From “The White Man’s Burden” poem’s lens, imperialism is justified as a “burden” that the representatives of the white race must undertake to help non-white races develop civilization [18]. Industry and communication were not allowed to be in non-Russian hands as Stalin said: “a number of peoples, mainly Turkic – about 30,000,000 in all – have not had time to pass through the period of industrial capitalism” [19].

Other forms of imperialism that were present in the Soviet Union are: nuclear colonialism (nuclear testing in Semey in 1947), starvation, and forced mass emigration (between 1926 and 1939, the Kazakh population went down by 22%) [20]. Nonetheless, the USSR is rarely talked about as an imperial force, but rather as Russia helping its neighboring nations.

American Imperialism

In a sense, the spread of capitalism and American culture denotes that the US is an empire and has imperialist ideology. In a lecture at Boston University, Noam Chomsky, an American linguist and philosopher, talked about how the United States is the only existing country that was founded as an empire by the founding fathers who emulated the Roman Empire. This emulation concretes the idea that the US is an empire–and has always been one [21].

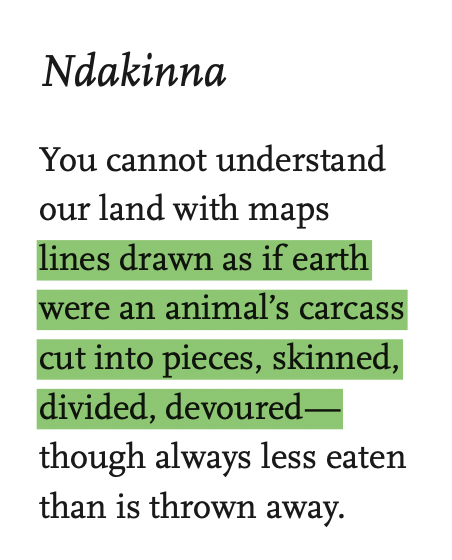

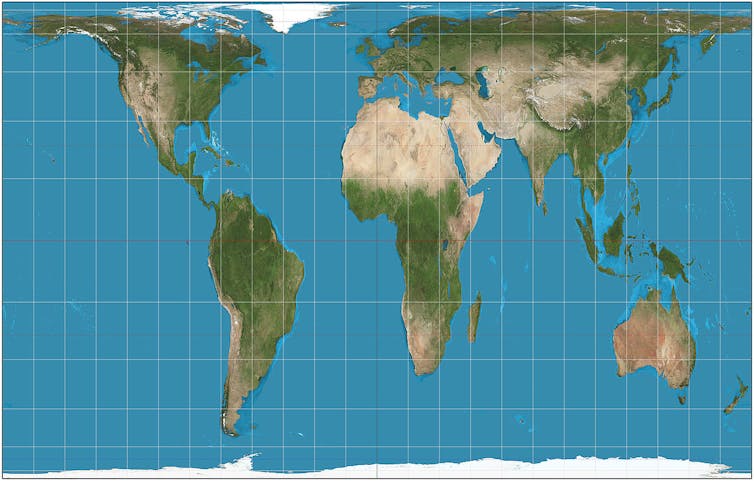

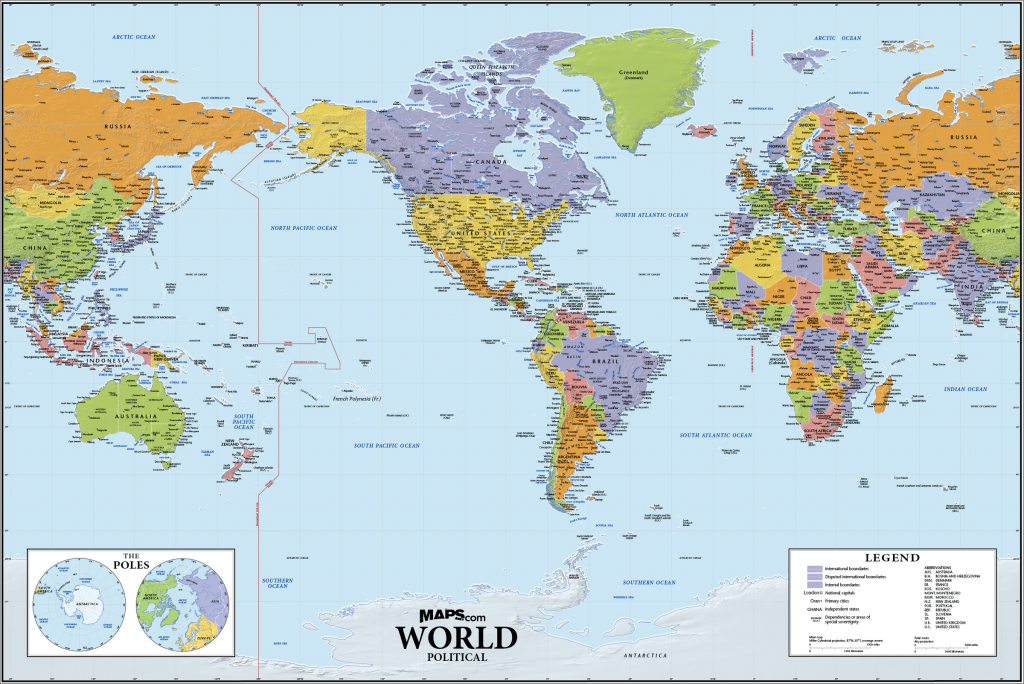

Similar to stolen labor, control over land is also an integral piece of colonialism. Though land acquisition and control are just pieces of imperialism, the power granted to imperial actors through controlling land cannot be overlooked. The role of maps and mapping as a practice often go unnoted in conversations concerning imperialism. As mentioned above, “territorial acquisition” is a key factor of imperialism. The simple phrase “territorial acquisition,” however, is an intensely vague attempt to encompass the relationship between imperialism and the land it is imposed upon. In an attempt to gain insight into what is meant by “territorial acquisition,” we examine imperialism and land through the lens of cartography.

The platitude “history is told by the victor” rings true in this instance as well: maps are made by those who conquer. The long history of imperialism and many nations, cultures who experienced it contributed to the development of various perspectives on this keyword. Our collective understanding of how the world is broken up and sorted is told by those who break up and sort, it’s an intensely biased understanding that carries a great amount of weight with it.

Maps are regarded as a scientific, empirical tool of understanding, they carry a sense of infallibility. The problem with the air of infallibility bestowed upon maps is that cartography is just as “subjective as any other artistic endeavor” [22]. Maps displayed in American schools often display a perspective skew that enlarges countries in the Northern Hemisphere; the global North dominates the map, both literally and visually [23]. Cartography proves itself as an imperial tool in this sense. The idea that the global North, primarily the U.S. and Western Europe, are dominant, larger than life forces, is subliminally planted and reinforced every time a map is pulled out in a classroom. Cartography is a more abstract way of controlling land, by controlling how land is perceived and labeled, but it is a tool of imperialism that weaponizes land all the same.

References

- Cornell University. n.d. “Imperialism.” Legal Information Institute. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/imperialism.

- Young, Robert. 2015. Empire, Colony, Postcolony. N.p.: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ortiz, Simon J. From Sand Creek. (Tucson: University of Arizona, 2000), 1-2.

- Fong, Sarah. “Racial-Settler Capitalism: Character Building and the Accumulation of Land and Labor in the Late-Nineteenth Century.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, no. 43:2, (2019).

- Williams, Walter. The Spirit and the Flesh: Sexual Diversity in American Indian Cultures. Boston, Beacon Press, 1992.

- Ibid

- “North American Indian Timeline (1492-1999).” Legends of America. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/notes/nativeamericanchron.html.

- Fong, Sarah. “Week Two: Race.” September 19, 2022.

- Kandaswamy, Priya. “Gendering Racial Formation.” Racial Formation in the Twenty-First Century. Edited by Daniel Martinez HoSang, Oneka LaBennet, and Laura Pulido. University of California Press, 2012.

- Ibid

- “Racial Capitalism and Prison Abolition.” ISSU. October 15, 2020.

- Ibid

- Picq, Manuela L. and Tikuna, Josi. “Indigenous Sexualities: Resisting Conquest and Translation.” Sexuality and Translation in World Politics. Edited by Caroline Cottet and Manuela L. Picq. E-International Relations Publishing, 2019.

- Boussebaa, Mehdi and Brown, Andrew D. “Englishization, Identity Regulation, and Imperialism.” Organizational Studies. University of Bath, 2016.

- Awad, Sumaya, and Brian Bean. Palestine: A Socialist Introduction. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books, 2020.

- Robinson, Cedric J. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. London: Zed Books, 1983.

- Sarah Fong, “Racial-Settler Capitalism: Character Building and the Accumulation of Land and Labor in the Late-Nineteenth Century,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, no. 43:2, (2019).

- Easterly, William. “The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done so Much Ill and so Little Good.” Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Caroe, Olaf. 1953. “Soviet Colonialism in Central Asia.” Foreign Affairs, October, 1953. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/1953-10-01/soviet-colonialism-central-asia.

- “Kazakhstan – History – Kazakhstan Under Soviet Rule.” n.d. LiquiSearch. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://www.liquisearch.com/kazakhstan/history/kazakhstan_under_soviet_rule.

- Boston University. “Noam Chomsky Lectures on Modern-Day American Imperialism: Middle East and Beyond.” YouTube video. April 7, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7PdJ9TAdTdA.

- De Armendi, Nicole. “The Map as Political Agent: Destabilising the North-South Model and Redefining Identity in Twentieth-Century Latin American Art.” North Street Review, vol.13 (2009), 5-17.

- Chakravarty, Chilpi. “These maps will show you why some countries are not as big as they look.” Published May 4, 2017, https://www.geospatialworld.net/blogs/maps-that-show-why-some-countries-are-not-as-big-as-they-look/

Contributors

Benicio Branco

Graciela Berman Reinhardt

Liv Fernandez

Sabina Saktaganova