Mixed Race

“My mom is Dominican-Cuban / My dad is from Chile and P.R. which means / I’m Chile Dominicanrican … But I always say I’m from Queens!”

Carla, IN The Heights

In the 2008 musical In The Heights, the character Carla sings “My mom is Dominican-Cuban / My dad is from Chile and P.R. which means / I’m Chile Dominicanrican … But I always say I’m from Queens!” [1] Though played up for comedic effect, this line speaks to a universal experience shared by many people of mixed descent. Here, Carla answers the question she has surely received countless times: “What are you?” The lyrics highlight both the internal and external forces that may cause mixed race individuals to question the boundaries of their racial identities.

With the release of the In The Heights movie in 2021, a TikTok trend quickly rose to prominence featuring people of mixed race descent using this song to share their stories and family backgrounds. As can be gleaned from the lyrics themselves, Carla – and the subsequent TikTok user – grapple with fitting a multitude of identities into a neatly packaged box. Carla overcomes this phenomenon, sharing her witty response, but the sentiment still speaks to the feeling many mixed people experience of searching for a synthesis of identity.

Definition

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, mixed race is defined as “Having parents or ancestors of different ethnic backgrounds.” [2] Similarly, the Cambridge Dictionary defines mixed race as “having parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents from different races.” [3] These definitions describe the term mixed race as it is generally used in the lexicon; but in thinking about a more holistic definition of mixed race, it is important to move beyond just phenotypic presentation of race. Phenotype refers to a person’s physical attributes which result from their genetic material. [4] While phenotype certainly plays a role in race and identity – after all race is constructed on phenotypic attributes – it cannot paint the whole picture. Therefore, we define being mixed race as a racial and social identity for individuals who come from two or more ethnic backgrounds, shaped not only by their physical appearance, but also by personal experience and the broader social, political, and historical power structures that influence the way others perceive them and the way mixed race individuals move through the world.

In this essay, we focus on the term mixed race, though “multiracial” and “multiethnic” are sometimes used in its place. Another common word used to describe mixed race individuals is biracial, which refers specifically to people who descend from two distinct racial backgrounds. “Mixed race,” on the other hand, does not delineate a specific number of ethnic backgrounds a person may descend from. We have chosen to define the term mixed race because it is the most common umbrella term used today.

Race as a Construct

The idea that race is a physically inherited and permanent characteristic has existed since the rise of European imperialism and settler colonialism. Social scientist Michael Banton explains the reasoning behind racial categories as “beliefs about biological differences are used to exclude persons from equal relations.” [5] Though race is often seen as unchanging, it has been constantly redefined to align with societal power dynamics. It has been used to justify chattel slavery, displacement of people from their lands, forced assimilation, exclusion, violence, and more. It is important to understand the standing of mixed race individuals in this context. As race is an ever-changing reflection of power and domination, those who do not neatly fit into one phenotypic category of race have been subject to racial inequities throughout history.

Highlighting this point, the National Human Genome Research Institute asserts that race is a “political and social construct that is fluid” and that it “has been used historically to establish a social hierarchy.” [6] Race is by nature unstable but nonetheless impacts the way in which people navigate the world. Mixed race individuals do not follow the distinct classifications that race provides. For example, a person of East Asian and African descent cannot neatly fit into one racial category. The quantification of race further complicates the racialization of mixed people. As a result, mixed race individuals are often forced into distinct racial categories that may invalidate parts of their identity. Those same individuals may feel pressure to identify with a certain race or may feel imposter syndrome when in the presence of another. Though racial categories are perpetually changing and inherently unstable, society still relies on race, as it plays an important role in the way we see the world. In short, though race is socially constructed, we will engage with it for this essay because race nonetheless constitutes many aspects of daily life. It certainly plays a crucial part in the identities and experiences of those who do not easily fit into solely one racial category.

The Politics of Being Mixed

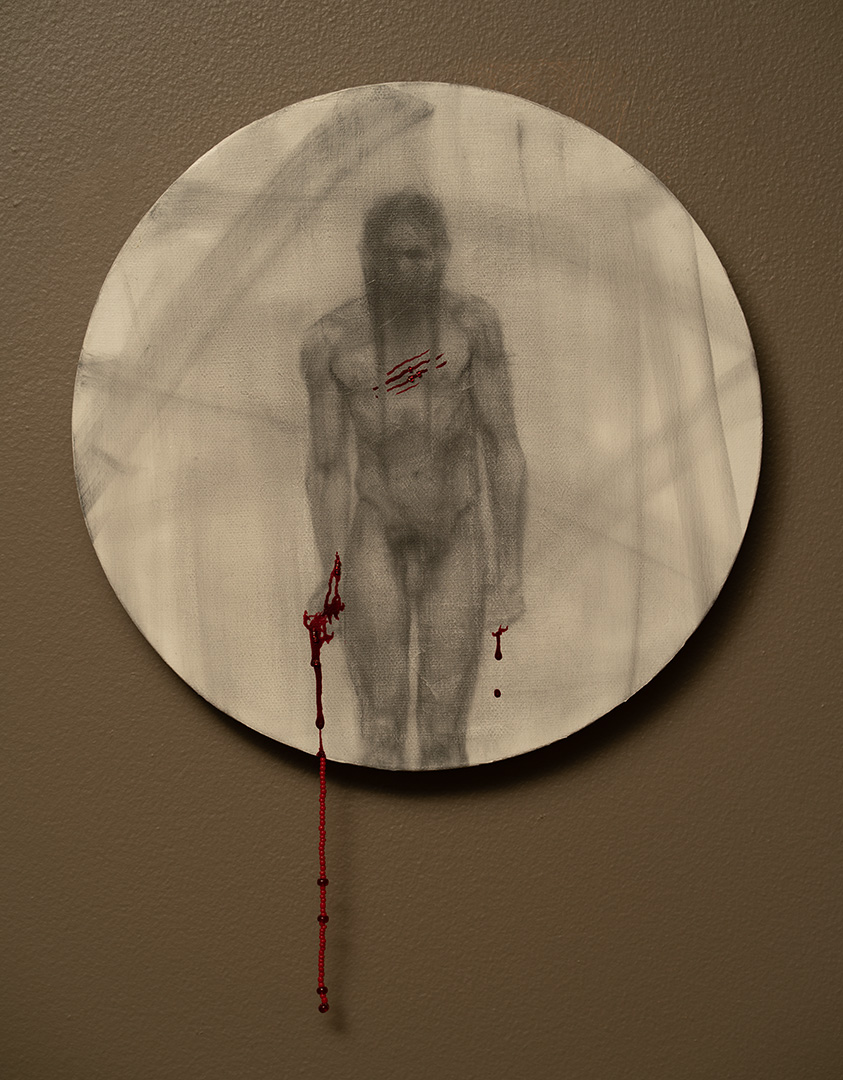

The Intersection of One Drop Rule and Blood Quantum

Throughout the history of the United States, the Government has enforced various rules to dictate the identities of mixed race individuals. During the 19th Century, the U.S. government’s policy of “Allotment and Assimilation” led to the official implementation of Blood Quantum. [7] When White settlers arrived on Indigenous American soil, they introduced the concept of Blood Quantum in order to limit the land rights of Native individuals. [8] The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 codified this practice into law as it mandated a “federal definition of Indianness based on blood.” [9] The act explicitly quantified the amount of “Native blood” indigenous people possessed, used this data to shrink who counted as Indigenous. Mixed Native individuals were often qualified as “less Native” in order to justify the stealing and settlement of their tribal lands. In this case, mixed race people faced a diminishing of their indigenous identity to justify the divide of their land.

Mixed race people have also had their racial identities shaped by the One Drop Rule. In the early 1900s, the One Drop Rule was a legal principle used to differentiate white citizens from other racial groups; it held the notion that a person with any trace of Black ancestry was automatically Black. The One Drop Rule can be qualified as expansive, as it considered individuals with any known Black ancestry as Black, in order to expand the working, subordinate class. The prevailing doctrine ensured that “a slave/criminal status will be inherited by an expanding number of ‘black’ descendants.” [10] Historically, Blackness was an indicator of inferiority and was based heavily upon phenotypic characteristics. Colonial enslavement was built upon those deemed “inferior,” and the One Drop Rule perpetuated this existence of a racial hierarchy. The law mandated that “a mixed race child be relegated to the racial group of the lower status parent.” [11] In this case, those mixed race people were given the status of African-Americans. As a result, mixed race individuals, even those who appeared phenotypically White, were subject to segregation and Jim Crow practices.

The One Drop Rule is just one of many unstable policies reliant upon shifting racial standards. Racial categories are perpetually changing, and those who are included or excluded in specific racial categories depend on the political environment of the day. Though Blood Quantum and One Drop Rule were created to pursue different political motives, both had an undeniable effect on mixed race people. Blood quantum and One Drop Rule are intertwined, as both target mixed race individuals and attempt to assign them strict racial identities. Both practices are carried out to pursue political motives and consequently neglect an individual’s preferred identity. Overall, both treat race as quantifiable. As a result, mixed race people have been subject to invalid claims to their land, enslavement, and discriminatory practices. One Drop Rule and Blood Quantum are methods that greatly oversimplify identity and simultaneously pursue nefarious political agendas.

The U.S. Census

Being mixed race has always carried significant political implications, particularly when it comes to how individuals are represented in the U.S. Census. The census was first conceived in 1790 as a measure to count who was inhabiting the United States, and it has been issued and collected every ten years since its inception. Historically, the census’s conception of race has been rather limited, but it has also changed with the times, reflecting the sentiments of the nation at any particular moment in history. The first Census in 1790 offered only three racial categories: “Free Whites,” “Slaves,” and “All Other Free Persons.” [12] Not only did this question reflect the stark reality of the institution of slavery, it also reinforced a reductive framework that ignored the diversity of racial identities present in the U.S. This effectively flattened all ethnic diversity into one box and negated the experiences of many communities within the Americas. In 1850, the Census introduced the category “mulatto” to refer to people of both Black and White ancestry. The term derives from Spanish and Portuguese and can be translated to mule. This reflects the way mixed race individuals were viewed: both as workhorses due to their Black ancestry and ties to slavery, and as a subhuman, interspecies mix. The Census once again reflected the political and social environment of the times. In the 1890 census, more mixed race categories were introduced such as “octoroon” and “quadroon,” which delineated the percentage of mixed race ancestry an individual had. [13]

The census working to expand categories of race came to a screeching halt in the 1930s with the rise of Jim Crow segregation. In the early and mid 20th century, anyone who appeared Black was considered Black by law. This again erased peoples’ identities and expanded the subordinate class in the United States. It wasn’t until 2000 that the census reintroduced the possibility of marking down a mixed race identity. People were able to check off more than one racial category, expanding peoples’ ability to correctly identify their racial makeup. When the census permitted respondents to select or write in multiple racial identities, the reported multiracial population saw a dramatic increase. For example, in 2010, the number of individuals identifying as multiracial rose by an estimated 70% compared to data collected using more restrictive questions. [14] This underscores the importance of flexible and inclusive census methods in capturing the true diversity of the population.

Although the census evolved over time, its historical limitations reflect a persistent struggle to account for the full complexity of racial identities. For mixed race individuals, the census’s narrow approach has led to much misrepresentation and exclusion, perpetuating a broader societal failure to recognize and value the diversity of the nation’s population.

In 1860, the census measured people by their relation to Blackness.

In 2010, attempts to be more inclusive were introduced.

The most recent attempt at inclusion came in 2020.

The census data impacts all aspects of bureaucratic affairs including redistricting and community representation, allocation of resources, and political power. [15] As such, the census serves as more than just a demographic tool; it is a critical mechanism for shaping how communities are recognized and supported within the political landscape. The evolving changes in the U.S. census not only reflect a growing demand for inclusivity but also highlight the complexities of how mixed race individuals choose to identify. These personal choices of identification carry significant political implications, particularly within the context of the census.

Mixed Race as Socialization

Socialization refers to the process by which individuals are exposed to others and in turn how they learn the norms of society. [16] The way mixed race individuals are socialized in their homes, communities, and society at large often plays an important role in shaping and forming their identities. Mixed race individuals do not exist in vacuums and their environments play a significant role in the development of their sense of identity and belonging.

Sociologist Jean Piaget along with many other psychologists and social scientists, theorized that the first 12 years of development are crucial for the formation of identity. The first decade of life encapsulates many of the critical periods for vision, language, and social bonds, leading to an emphasized importance on how young children are socialized. [17] We have come to understand identity as fluid and malleable to the changes throughout life, but socialization is greatly influential in the early years of consciousness. For example, if mixed race children are socialized with strong connections to all parts of their identities, they may feel equally connected to the different aspects of their racial backgrounds and their subsequent communities. Similarly, a child who is only immersed in the culture of one community may have a different relationship with other aspects of their racial identity. Again, there is no one-size-fits all prescriptive outcome based on the way a child is socialized, but there is often a correlation between socialization and identity.

On identity, Jamaican-British sociologist Stuart Hall provides some insight. In his essay “Who Needs Identity?” Hall discusses identity as a meeting point – or what he calls a “point of suturing” – between the discourses surrounding our identities and the ways we become subjects of our identities. [18] Put simply, Hall views identity as political, everchanging, and socially constructed. While it is true that identities are socially constructed, this may push back against the ideas presented by the phenotypic view of race as a fixed identity. But we know that race is in fact unfixed and inherently unstable, so this view of identity complements the notion of race as a socially constructed, ever changing category that still has very real implications and is tied deeply to peoples’ sense of self. Thus we have put forth our definition of mixed race as the meeting ground between these two forces.

Professor of Mixed Race Studies Silvia Christina Bettez adds to Hall’s theorization in her piece “Mixed-Race Women and the Epistemologies of Belonging.” In the essay, Bettez interviews six college aged women of mixed descent. Each of the six women articulate their identities and the life experiences that have led them to view themselves in the way they do. Bettez works off the theories of Stuart Hall, quoting “The notion of effective suturing of the subject to a subject-position requires, not only that the subject is ‘hailed,’ but that the subject invests in the position.” [19] Hall effectively argues that it is not enough for someone to be hailed as something, rather there needs to be active buy-in or investment from the subject to be seen as such. Bettez brings quotes Hall while discussing one of the participants, Brianna. Brianna is the daughter of a Choctaw mother and an African-American father, and she was raised by adoptive White parents. Brianna exemplifies the importance of socialization in the contexts of Hall’s theorization, as she moved through much of her life feeling untethered to any one identity. Brianna was not raised around Choctaw community or family and thus spoke about feeling little to no affiliation or connection to that side of her identity. Again, socialization it is not a zero-sum game, but Hall and Bettez highlight the role of socialization in forming and solidifying identity.

Questions from The Video “Do All Multiracial People Think the Same?”“People think I’m hot because I’m mixed race”

“I’m allowed to use slurs as long as it’s a part of my racial identity”

“How you pass is more important than your actual race”

“I’ve tried to hide some of my racial identity”

“I’ve used my race to my advantage”

“The issue of racism can be solved by interracial love”

As mentioned above, there are a plethora of different ways for mixed race individuals to be socialized. Jubilee, a YouTube channel focused on bringing together a wide variety of perspectives, posted a video in Spring of 2020 titled “Do All Multiracial People Think The Same?” [20] In the video, one of the participants, Annette, explains that she spoke Cantonese growing up and thus worked primarily in Chinese spaces. Though she may be phenotypically hailed as Black, Annette points to the fact that in school, many of her friends were Asian, highlighting that socialization can play a key role in delineating social bonds, work environments, and views of self. Another participant in the video, Amblashia, begins her interview by stating “My ethnicity is Filipino and Black. I do feel more inclined to my Black side more than my Filipino side.” Though she does not go into detail, Amblashia embodies the idea that people may feel more inclined to one identity over another based on external factors as well as internal factors. Who we are surrounded by what media we consume, and even the messages we receive from those within our own communities play a role in how identity is formed and perpetuated.

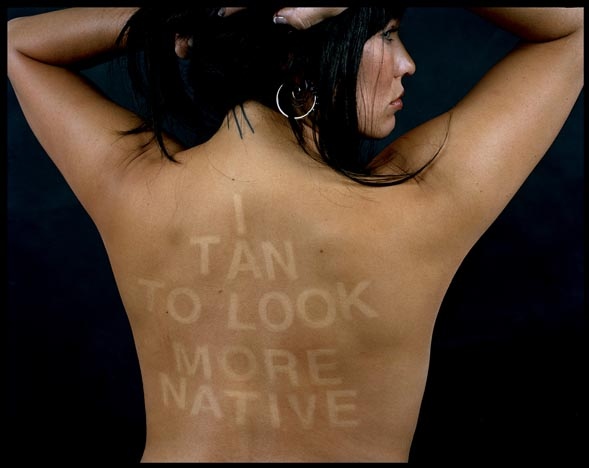

Racial Passing

Racial passing can be defined as “a phenomenon in which a person of one race identifies and presents himself or herself as another (usually white).” [21] The act of racial passing was especially prevalent during the Jim Crow era, as individuals sought to avoid racial oppression. Passing is another practice that perpetuates the hierarchical structure of race in American society. Those who are mixed race may participate in such a practice, though passing is not exclusive to multiracial individuals. Motivations often include wanting to “blend it,” seeking acceptance from peers, or attempting to avoid a certain stigmatized identity. [22] Passing relies heavily upon phenotypic features and the perception of others regarding those characteristics. The act of passing is intentional, but there are instances where others try to dictate a person’s racial identity.

“No matter how many tears I’ve shed because I’m not connecting with my family or my culture in a way that I would like to, or because the waitress thinks I’m the babysitter when I go out with my family — none of that would compare to the tears that I would shed for presenting phenotypically Black and the disadvantages and the violence that I would face because of that.”

Halsey, musical artist [23]

“Not ‘X’ Enough”

A common phenomenon experienced by mixed race individuals is being told that they are not “[insert race here] enough.” Some mixed race people face ostracization or pressures from certain communities because they don’t meet the standard set out for them. In the 2020 issue of The Brunswick Review, Hayley Singleton, a mixed race women working for The Brunswick Group, penned an article titled “Too Black & Not Black Enough. ” In it she discusses the world’s perception of her Blackness in relation to her Whiteness, writing “As a woman of mixed race I am in the unique position of existing in two worlds. I am consistently both too Black and not Black enough, living in an ambiguous middle ground between two often opposing communities.” [24] Sometimes the ascribing of being not “Black enough,” to use this example, comes from within the very community to which someone belongs. This view works to undermine individual and communal identity, as well as devaluing the relationships people have to their own lived experiences.

Representation in Media

Ginny & Georgia (2021-)

One infamous scene from the Netflix series Ginny & Georgia showcases the struggles a young biracial girl faces as she navigates her identity. In this scene, she clashes with her boyfriend, who is also mixed race. They argue back and forth, each claiming that the other is more connected to their “white half,” with the boyfriend stating that together they “make a whole white person.” This exchange reflects a common and oversimplified view of mixed race identity, where people are seen as “half and half” based on biological heritage. However, as the scene continues, the boyfriend lists Black stereotypes that Ginny does not fit and ends by claiming that if she wanted to play the “Oppression Olympics,” he could go on. [25] Though the dialogue is somewhat exaggerated, it highlights the internal insecurities both characters feel about not being “Asian enough” or “Black enough.” They attack each other based on social expectations of their race, while also acknowledging that their identities have been affected by both historical and social oppression.

This representation of a mixed person’s experience highlights the internal struggles individuals may face; however, the portrayal of Ginny’s character has somewhat problematic implications, as it plays into the stereotype of the absentee Black father and centers Ginny’s white mother. This trend is seen in several Netflix productions, such as Lara Jean in To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and Mary Anne in The Babysitter’s Club. [26] Moreover, this portrayal of being mixed seems to focus on her whiteness as the norm, inadvertently perpetuating the notion that a mixed race identity can only be understood in relation to whiteness.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023)

“Everyone keeps telling me how my story is supposed to go. Nah… I’ma do my own thing. Sorry, man, I’m going home.”

Miles Morales, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023)

In comparison, fictional mixed race characters without a White parent are emerging more in the media. The sequel to the critically acclaimed 2018 film, Spider-man: Across the Spider-verse (2023) continues the mantle of the masked Marvel spider superhero. [27] Unlike other Spidermans, Miles Morales differs from Peter Parker’s prototype. Within the Spiderman multiverse the majority of spidermen are nerdy White teenage boys. However, Miles Morales emerges within Earth-1610 as the protective force of Spiderman in Brooklyn. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse delves deeper into the character of Miles Morales as an Afro-Latino Spiderman, both as he navigates his personal life as he hides his superhero identity from his parents, and his conflicting feelings about what is expected of him as a Spiderman. Across the Spider-Verse emerges as a landmark superhero movie that goes beyond superficial themes of strength and absolute justice. Instead, the journey of Miles Morales incorporates his deeply entrenched cultural values and familial connections which are inextricably tied to his motivation to be a hero.

Unlike other cinematic representations of mixed people, Miles Morales doesn’t struggle with his sense of belonging in a social context due to his mixed identity. Instead, the conflict of the film and the interworks of his character involve what the additional characters in the film expect of him. In the beginning scene, Miles is shown in the counselor’s office discussing his college prospects, with a comedic twist: his worst grade is in Spanish, despite his mother being from Puerto Rico and often speaking to him in the language. His counselor later says, “Your name is Miles Morales, and you’re from a struggling immigrant household” (28:31). His parents then clarify that their family is not struggling and that his father is set to become police captain the following week. Nevertheless, the White counselor insists it doesn’t matter in order to frame the story as intended. This tokenizing that Miles is subject to by his school is not uncommon for mixed people, specifically Afro-Latinos. Miles demonstrates how his mixed identity is not only a racial identity, but an identity intertwined with broader political and social power structures. His relationship with his identity and his parents give further insight to how his motivations as Spiderman differ from his White counterparts. Moreover, Miles inserts a refreshing representation of mixed people. He is unapologetically proud of his culture, and his mixed identity is not a source of internal struggle; rather, it is his love for his racially blended family that motivates him to continue as Spiderman.

Closing Remarks

In his work “The Hapa Project,” artist Kip Fulbeck asked mixed race people to answer the question “What are you?” in their own words. Subjects were then photographed 15 years later and asked to respond to the same question. Each individual underwent an identifiable change in how they described themselves. While initially they focused on their race and other physical attributes, as they grew older they described themselves as fathers, friends, caretakers. Many subjects still discussed their race – and especially their mixed race identities – but the evolution of their answers points to a more holistic view of identity and self.

The tendency to homogenize experiences encountered by mixed peoples is a denial of individual struggles, achievements, and personal narratives. Recognizing race outside of physical appearance is crucial to grasp the historical, political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions of identity within society. By asserting agency beyond the conflicts or roles imposed on them, mixed race individuals affirm their right to be seen and valued as whole, complex individuals beyond the perceived confines of racial identity.

References

[1] Miranda, Lin-Manuel, “Carnival Del Barrio,” In The Heights, Janet Dacal. June 3, 2008. Ghostlight Records.

[2] Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Mixed-race,” accessed November 17, 2024.

[3] Cambridge Dictionary, s.v. “Mixed-race,” accessed December 11, 2024.

[4] National Human Genome Research Institute. Phenotype. Updated December 11, 2024.

[5] Banton, Michael. “Race as Social Construct.” Cambridge University Press EBooks, April, 196–235. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511583407.008.

[6] National Human Genome Research Institute. Phenotype. Updated December 11, 2024. https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Phenotype

[7] National Geographic Society. “The United States Government’s Relationship with Native Americans | National Geographic Society.” Education.nationalgeographic.org. National Geographic Society. June 2, 2022.

[8] National Geographic Society

[9] Ellinghaus, Katherine. “Blood Will Tell,” August 2017. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1qv5ptw.

[10] Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor | Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.” Utoronto.ca. September 8, 2012. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630.

[11] Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang

[12] Parker, Kim, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Rich Morin, and Mark Hugo Lopez. “Chapter 1: Race and Multiracial Americans in the U.S. Census.” Pew Research Center. June 11, 2015. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/06/11/chapter-1-race-and-multiracial-americans-in-the-u-s-census/.

[13] Perez, A. D., and Hirschman, C. “The Changing Racial and Ethnic Composition of the US Population: Emerging American Identities.” Population and Development Review 35, no. 1 (March 2009): 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00260.x.

[14] Parker et alt. “Chapter 1”

[15] United States Census Bureau. “What We Do.” https://www.census.gov/about/what.html.

[16] Little, Willian and Ron McGivern. Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition. BC Open Textbook Project, 2014. Chapter 5.

[17] Malik, Fatima and Raman Marwaha. National Library of Medicine: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Cognitive Development. Updated April 23, 2024.

[18] Hall, Stuart. “Who Needs Identity?.” In Questions of Cultural Identity. Sage Publications, 1996.

[19] Bettez, Silvia C. “Mixed-Race Women and the Epistemology of Belonging.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 31, No. 1 (2010), pp. 142-165.

[20] “Do All Multiracial People Think The Same?” Jubilee, March 18, 2020. Video, 13 min., 11 sec.

[21] Khanna, Nikki, and Cathryn Johnson. “Passing as Black: Racial Identity Work among Biracial Americans.” Social Psychology Quarterly 73 (4): 380–97. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272510389014.

[22] Khanna, Nikki, and Cathryn Johnson

[23] Bate, Ellie. “Halsey Said She Has “For Sure” Benefited From Passing As White.” Buzzfeed News. July 14, 2021. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/eleanorbate/halsey-white-passing-allure-cover-interview

[24] Singleton, Hayley. “Too Black & And Not Black Enough.” Brunswick Review: A Journal of Communication and Corporate Relations, No. 20 (2020): 60.

[25] Lampert, Sarah. Ginny & Georgia. Season 1, Episode 8. Netflix, February 24, 2021.

[26] Radulovic, Petrana. “Netflix Has a Troubling Problem with Its Biracial Characters.” Polygon, March 9, 2021.

[27] Dos Santos, Joaquim, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson, directors. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Sony Pictures Animation, 2023.

Bibliography

Banton, Michael. “Race as Social Construct.” Cambridge University Press EBooks, April, 196–235. 1998.

Bate, Ellie. “Halsey Said She Has “For Sure” Benefited From Passing As White.” Buzzfeed News. July 14, 2021.

Bettez, Silvia C. “Mixed-Race Women and the Epistemology of Belonging.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 31, No. 1 (2010), pp. 142-165.

Bonham, Vence L. 2023. “Race.” Genome.gov. 2023.

Cambridge Dictionary, s.v. “Mixed-race,” accessed December 11, 2024.

Cohn, Vera, Anna Brown, and Mark Hugo Lopez. “Only About Half of Americans Say Census Questions Reflect Their Identity Very Well.” Pew Research Center. May 14, 2021.

“Do All Multiracial People Think The Same?” Jubilee, March 18, 2020. Video, 13 min., 11 sec.

Dos Santos, Joaquim, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson, directors. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Sony Pictures Animation, 2023.

Ellinghaus, Katherine. “Blood Will Tell,” August 2017.

Lord, Erica. ericalord.com. “The Tanning Project,” n.d.

Furedi, Frank. Rethinking “Mixed Race.” 2015.

Hall, Stuart. “Who Needs Identity?.” In Questions of Cultural Identity. Sage Publications, 1996.

Khanna, Nikki, and Cathryn Johnson. “Passing as Black: Racial Identity Work among Biracial Americans.” Social Psychology Quarterly 73 (4): 380–97. 2010.

KQED. “‘What Are You?’ Artist Kip Fulbeck Gives Mixed-Race People a Chance to Answer in Their Own Words,” n.d.

Lampert, Sarah. Ginny & Georgia. Season 1, Episode 8. Netflix, February 24, 2021.

Little, Willian and Ron McGivern. Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition. BC Open Textbook Project, 2014. Chapter 5.

Malik, Fatima and Raman Marwaha. National Library of Medicine: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Cognitive Development. Updated April 23, 2024.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel, “Carnival Del Barrio,” In The Heights, Janet Dacal. June 3, 2008. Ghostlight Records.

National Geographic Society. “The United States Government’s Relationship with Native Americans | National Geographic Society.” Education.nationalgeographic.org. National Geographic Society. June 2, 2022.

National Human Genome Research Institute. Phenotype. Updated December 11, 2024.

Nelson, Winona. “Blood Quantum.” Graphite powder, acrylic, and glass beads on canvas.

Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Mixed-race,” accessed November 17, 2024.

Parker, Kim, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Rich Morin, and Mark Hugo Lopez. “Chapter 1: Race and Multiracial Americans in the U.S. Census.” Pew Research Center. June 11, 2015.

Perez, A. D., and Hirschman, C. “The Changing Racial and Ethnic Composition of the US Population: Emerging American Identities.” Population and Development Review 35, no. 1 (March 2009): 1–51.

Prewitt, Kenneth. “What Is Your Race?: The Census and Our Flawed Efforts to Classify Americans.” Princeton University Press, 2013. JSTOR. Accessed 19 Nov. 2024.

Radulovic, Petrana. “Netflix Has a Troubling Problem with Its Biracial Characters.” Polygon, March 9, 2021.

Rockquemore, Kerry A. “Between Black and White Exploring the ‘Biracial’ Experience.” Race and Society 1 (2): 197–212. 1998.

Singleton, Hayley. “Too Black & And Not Black Enough.” Brunswick Review: A Journal of Communication and Corporate Relations, No. 20 (2020): 60.

Stanford School of Business. “Blood Quantum: Blood Quantum: A Knife That Cuts Both Ways | Lacey Calac Dunne, MSx ’23”. Youtube. 5:21-6:10

Tiktok.com. “TikTok – Make Your Day,” 2024.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor | Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.” Utoronto.ca. September 8, 2012.

United States Census Bureau. “What We Do.”

VenusMosaic “Mixed Race Wall Art.”

Contributors

Vanessa John

Yael Waxman

Arianna Espindola