Police

The word “police” has a lineage that flows from the ancient Greek “polis” (city-state) through Middle French, where it initially denoted civil administration rather than law enforcement. While modern American policing evolved from the English model of “keeping the king’s peace,” its rapid expansion in the United States—a nation founded in opposition to monarchy—seems paradoxical [2]. This apparent contradiction is resolved by understanding the institution’s primary function in early America: maintaining racial hierarchies, particularly through the enforcement of slavery and subsequent systems of racial control. [3] While the modern notion of police as a civil force emerged from England’s tradition of maintaining “the king’s peace,” the American context specifically shaped its evolution in distinctly different ways. [4] Despite the United States’ rejection of monarchy, police forces expanded rapidly, largely driven by the imperatives of racial control and the institution of slavery in the South, while simultaneously developing as a mechanism for regulating immigrant behavior in the North. Scholars Parks and Kirby offer a critical definition, arguing that the police force “was developed to protect and retain the interests of the wealthy and those in political power.” [5] This perspective aligns with historical evidence of how policing emerged and evolved in America, serving as both slave patrols in the South and as regulators of immigrant communities in the North. [6]

Today, the definition and function of policing remain subjects of intense debate, reflecting deep societal divisions in how law enforcement is perceived and experienced. The Oxford Dictionary offers a seemingly neutral definition: “the civil force of a national or local government, responsible for the prevention and detection of crime and the maintenance of public order.” [7] Yet this seemingly straightforward description carries complex implications, particularly in its emphasis on the “maintenance of public order”—a concept inherently defined by governmental authority [8]. This official definition exists in tension with sharply contrasting public perspectives. While some view police as the protectors of social stability and public safety, this view often overlooks the disproportionate harm inflicted on oppressed communities—a pattern that has persisted since the institution’s founding. While on this webpage we focus on racial and ethnic minorities, policing has also disproportionately targeted poor people, LGBTQ+ individuals, and immigrants—reflecting and reinforcing existing social hierarchies rather than protecting all members of society equally.

Speaking against the idea of the police as a neutral force that ensures public safety, critics, particularly those from communities most impacted by law enforcement, challenge the notion of police as neutral guardians of public safety. Drawing oftentimes from firsthand experience with police violence and incarceration, critics argue that law enforcement exists primarily to protect property and maintain social hierarchies. In their analysis, police power serves as a mechanism for preserving racial and economic inequalities within America’s colonial framework, rather than providing equal protection under the law. [9] The stark divergence in these interpretations reflects not just different political stances, but fundamentally different lived experiences with law enforcement. While some citizens have never experienced being threatened by police presence, others navigate daily life with the burden of historical trauma and present-day concerns about discriminatory enforcement practices. Understanding this divide—and the history that created it—is crucial for any meaningful discussion of policing in America. Our definition of policing centers on its institutional roots and continuing role in upholding colonial power structures and racial hierarchies—a system that historically protected colonial settlements while enforcing policies that continue to result in disproportionate harm and mortality rates within BIPOC communities. We understand policing as a foundational mechanism for maintaining the territorial and political authority of the United States.

History

The story of American policing is one of power transformed—revealing how systems of control evolved from colonial times to shape modern law enforcement. At its foundation lies a profound shift in the very nature of state authority. As historian Jill Lepore observes in “The Invention of the Police,” the enforcement of slavery marked a fundamental shift in state power: “The government of slavery was not a rule of law. It was a rule of police.” [12] While law establishes rights, procedures, and limitations on authority, policing of enslaved people operated largely through direct force and discretionary power. Even when laws existed governing the treatment of enslaved people, the day-to-day enforcement relied more on immediate police authority than on legal process. Police officers could stop, search, detain, and punish enslaved people without the procedural protections or due process that characterized the formal legal system’s treatment of free citizens.

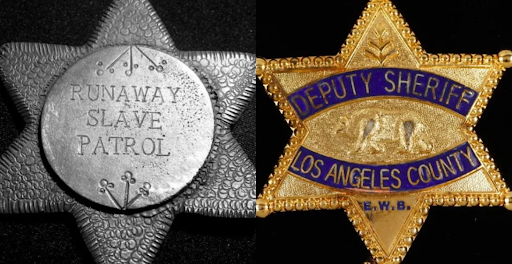

Early American policing emerged through two parallel channels: Indian Agents who controlled Native American populations, and slave patrols that maintained the institution of chattel slavery. [13] This dual origin was evident in colonial Philadelphia, where the governor proposed replacing the civilian night watch with militia forces—a move that signaled a fundamental transformation in public safety. Militias had historically been reserved for addressing external threats: French military forces, Native American resistance to colonial expansion, or potential slave uprisings. [14] In contrast, Philadelphia’s new militias represented increased state control over its own people.

The South developed a particularly brutal model of law enforcement. As Nicholas Salimbene documents in “The Genesis of Formal Police Agency Creation in U.S. Cities,” while Northern police forces emerged to control immigrant populations in urban areas, Southern law enforcement explicitly focused on maintaining control over enslaved people across sprawling plantation landscapes. [15] These slave patrols conducted systematic searches and enforced strict behavioral codes among enslaved populations.

The reach of state violence extended into the American Southwest. As Red Nation Rising documents, the first frontier police forces emerged from scalp hunters who were recruited to pursue Apache people in Indian Country during the 1840s and 1850s, effectively transforming mercenary violence into state-sanctioned law enforcement. [16]

The post-Civil War era witnessed not the dissolution of these systems but their transformation. Reconstruction saw slave patrols evolve into militia-style groups that enforced Black Codes—restrictive laws limiting freed people’s access to employment, wages, voting rights, and basic freedoms. When the 14th Amendment technically nullified these discriminatory Black Codes in 1868, they were swiftly replaced by Jim Crow laws, with police serving as the primary enforcers of racial segregation through brutal and systematic oppression. [17]

In the beginning of the 20th century, American policing continued to grow in a systematic evolution known as militarization.

The Militarization of Police

The militarization of American policing—the adoption of military tactics, equipment, training, and culture into civilian law enforcement—took a decisive turn in 1909 under August Vollmer, Berkeley’s police chief. Vollmer deliberately reshaped civilian policing by importing military methods into everyday law enforcement. He adapted combat tactics and weapons that had been used against Native Americans in western territories and colonized peoples in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, bringing colonial warfare methods to domestic policing. His training model, widely replicated nationwide, heavily recruited veterans of America’s colonial wars, embedding their combat experience into routine police work. [19] This approach signaled a crucial shift: police departments were no longer explicitly tasked with maintaining order, but adopting the structure, equipment, and mindset of military forces. As Detroit’s police commissioner declared, a police captain should command the same public respect as their military counterpart—reflecting how deeply military culture had penetrated civilian law enforcement.

This militarization intensified during the Johnson administration’s “war on crime” in the 1960s. [20] The Law Enforcement Assistance Act authorized supplying local police with military-grade weapons fresh from Vietnam’s battlefields. The subsequent 1968 crime bill established the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, channeling federal funds to thousands of crime-control projects. Even social program funding—intended for youth employment, health, education, and welfare—was frequently diverted to police operations.

The 1997 creation of the 1033 Program marked a significant acceleration in police militarization, enabling the Department of Defense to transfer surplus military equipment directly to civilian police departments. What began as transfers of basic supplies—clothing and office equipment—soon expanded into a pipeline for military-grade weapons, armored vehicles, and tactical gear. [21] This process intensified dramatically post 9/11. Under the banner of counterterrorism, federal funding flooded into local law enforcement agencies. Even small-town police departments began acquiring surveillance technology, armored personnel carriers, and combat-style tactical training previously reserved for military operations. [22] This transformation fundamentally altered the relationship between police and the communities they serve, as routine law enforcement increasingly resembled military operations. Muslim communities were especially affected; for example, the New York Police Department collaborated closely with the CIA, using military surveillance devices and tactics to infiltrate the Muslim communities. Initiatives like the ‘Demographic Units’ allowed police officers who shared the same ethnic background as these communities to surveil as they “treated basic acts of daily living as potential crimes, surveilling Muslims in their homes, mosques, schools, restaurants, coffee shops, and universities.” [23] This shift gave police officers a greater power and justification to adopt these military-like roles under the guise of “doing everything it can to make sure there’s not another 9/11 here and that more innocent New Yorkers are not killed by terrorists” as said by an NYPD Spokesperson. [24]

The militarization of police within the United States is also highlighted through various police programs in which officers are sent overseas to learn directly from other military organizations also referred to as the Deadly Exchange. One significant example is the Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange, which “trains top U.S. law enforcement officials in Israel and in other countries to learn valuable security tactics from their counterparts.” [25] The Georgia police learn and share “discriminatory and repressive policing practices…including racial profiling, massive spying and surveillance, deportation and detention, and attacks on human rights defenders.” [26] By working hand and hand with oppressive military forces, these policies become further embedded into local policing highlighted during the Stop Cop City movement in Atlanta in which police violently repressed organizers, shooting and killing unarmed protestors.

Alongside training, police officers also receive tools that assist in repression like Skunk Water, which is “ a liquid compound with an overpowering odour that has been described by those who have experienced it as the smell of sewage mixed with rotting corpses.” [27] This product was developed in Israel as a means of riot dispersal but has now become a new way of both physical and psychological torture as people who encounter the smell experience “intense nausea, obstructing normal breathing, causing violent gagging and vomiting,” and the scent stays in the air and sticks to clothing and skin for days on end [28]. Recently, police departments have been purchasing Skunk Water in hopes of using it in the same way like Arizona’s police department. Arizona’s sheriff states that as soon as a protest becomes violent, “then I will deploy the skunk water and arrest those that remain.” [29] The lack of clear guidelines that distinguish a peaceful protest from a violent one allow the police to determine when they should get involved and in turn use these military grade tools against civilians.

With increased access to militarized equipment and tactics, “Police often think of themselves as soldiers in a battle with the public rather than guardians of public safety” [31] Today’s police forces continue to reflect this military propensity, with officers disproportionately drawn from veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. This ongoing connection between military service and domestic policing perpetuates a pattern established over two centuries ago, when the king’s men became the state’s men, armed with increasingly sophisticated tools of social control.

Police Violence and Brutality

The issues of police violence and brutality are directly connected to the origins of policing (as highlighted in our history section) as a way to uphold capitalist and racial hierarchies, and to this day these issues still persist. The Civil Rights Movement and the American Indian Movement both exposed the violent role of police in enforcing racist ideologies with the police attacking peaceful protesters in Selma and arresting and brutalizing the Mashpee 9, a group of Indigenous activists defending their rights to self-determination. With the additional increasing militarization of police, there is a sort of manufactured consent for police to wield extensive amounts of force against the public as they enter situations, heavily armed which leads to fear and escalation. This was seen in the death of Breonna Taylor, as police entered her home in the night without uniform or stating their presence as if they were a part of an operation and shot 32 bullets in the home, killing her. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, sparked by the unjust death of Trayvon Martin, created a global campaign addressing police violence and brutality in America and across the world against Black people. Movements like BLM in the present draw on the legacies of prior activism as they call for the abolition and defunding of police and reinvestment into community-led programs.

There are far more victims of police brutality and violence, far more than can be covered here, each deserving of justice and remembering. Victims of police violence are often portrayed as criminals, even when wrongfully detained or murdered . Works of art and poetry have been created to combat this narrative, humanize these individuals, and amplify their stories. Ross Gay’s poem “A Small Needful Fact” beautifully celebrates the life of Eric Garner, a victim of police violence in 2014, with a heartbreaking reference to Garner’s last words: “I can’t breathe.” [32] Gay’s poem insists on making Garner’s story known beyond just a statistic.

A Small Needful Fact Is that Eric Garner worked for some time for the Parks and Rec. Horticultural Department, which means, perhaps, that with his very large hands, perhaps, in all likelihood, he put gently into the earth some plants which, most likely, some of them, in all likelihood, continue to grow, continue to do what such plants do, like house and feed small and necessary creatures, like being pleasant to touch and smell, like converting sunlight into food, like making it easier for us to breathe. - Ross Gay [33]

Graphic arts such as printmaking are an integral part of anti-police activism due to their propensity towards multiplicity. Chicano artist Oree Originol’s print series Justice for Our Lives, featuring over 100 portraits of victims of police violence, communicates the sheer number of lives taken by the police. Originol “encourages users to circulate [his prints] on social media and print them for use in protests or in urban interventions,” exemplifying how the duplicative nature of graphic arts lends itself to activism [34]. This circulation then allows these stories to become more accessible to the greater public.

Art is also used to call public attention to the horrors of police brutality. “Fred Hampton’s Door 2” is a 1974 piece created by Boston artist Dana Chandler in response to the 1969 killing of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton. In Chandler’s piece, the colors are representative of the Pan-African flag, symbolizing solidarity among the African diaspora. The “U.S. Approved” badge points to the chilling reality that the U.S. continually condones the murder of Black people at the hands of the police. The work is imposing and powerful, with its life-size stature conveying the harsh reality of police brutality. Curator Liz Munsell describes it as a “visceral, bodily understanding of this sort of violence.” [36] Works like Chandler’s challenge definitions of police that paint policemen as protectors and upholders of law and order by making the victims of police brutality impossible to ignore. [37], [38]

Policing Political Resistance

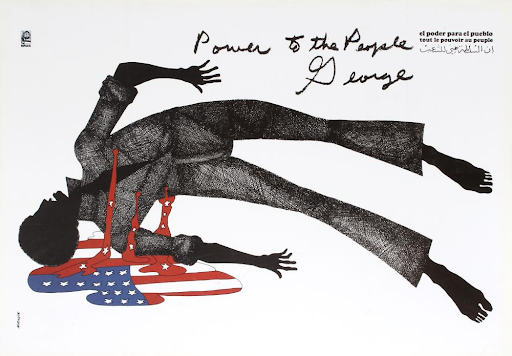

Political prisoners and activists have provided crucial insights into law enforcement’s function as an instrument of state control and property protection, often paying a profound personal price for their resistance and analysis. George Jackson emerges as a central figure in this critical tradition. Sentenced to “one year to life” for allegedly stealing seventy dollars—a draconian punishment reflecting the racial inequities of the justice system—Jackson transformed his imprisonment into a platform for revolutionary consciousness. [40] His incarceration, marked by dehumanizing conditions, became longer and harsher as he developed and shared his understanding. As Walter Rodney commented, Jackson’s Blackness could serve not as a “badge of servility” but as a “banner for uncompromising revolutionary struggle.” [41] This awakening ultimately cost him his life; he was killed because of his powerful influence on fellow prisoners. Writing from Soledad Prison, Jackson provided a particularly incisive analysis in his “Prison Letters.” He characterized police as instruments of “neoslavery,” pushed forward by those wielding “the unnatural right over property.” [42] Jackson’s critique dismantles the myth of the “thin blue line,” revealing how police protect not ordinary citizens but rather “the unnatural right of a few men to own the means of all of our subsistence.” [43] In his analysis, the police officer becomes “merely the gun, the tool, a mentally inanimate utensil” serving a larger system of exploitation. [44]

This perspective resonates with Leonard Peltier’s bitter observations from his experience as a Native American activist. His words cut through to the systemic nature of oppression: “Truth is, they actually need us. Who else would they fill up their jails and prisons with in places like the Dakotas and New Mexico if they didn’t have Indians? Think of all the cops and judges and guards and lawyers who’d be out of work if they didn’t have Indians to oppress! We keep the system going.” [46] Other prominent activists and political prisoners have contributed to this critical framework, including Mumia Abu-Jamal, Elaine Brown, and Huey Newton. The Black Panther Party translated theory into direct action through their armed patrols, monitoring police officers to protect their communities from brutality—a tactical response to systematic oppression. [47] Jackson’s definition of fascism as “a police state wherein the political ascendancy is tied into and protects the interests of the upper class—characterized by militarism, racism, and imperialism” maintains its relevance today. [48]

This was dramatically illustrated in early 2024 when U.S. airman Aaron Bushnell’s self-immolation protest against Palestinian genocide was met with a police officer pointing a weapon at his burning body—a stark symbol of how law enforcement prioritizes property and state interests over human life. [50] Mumia Abu-Jamal’s artistic work, exhibited at Brown University, carries forward this critique. His poem “Rights Humane” poses the essential question: “What good is human rights, without the right to life… for exposing this demonic system is critical, for building a Revolution against all that’s wrong is natural.” [51] These words, written from behind prison walls, underscore the fundamental contradiction between policing’s stated purpose and its actual function in maintaining systems of property and power.

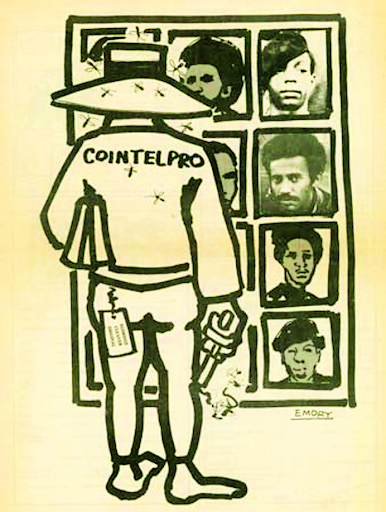

The role of police in maintaining state power extends far beyond routine patrols and into sophisticated mechanisms of political repression. While local police departments handle day-to-day enforcement of property rights and social order, federal law enforcement—specifically through programs like COINTELPRO—elevate this control to a national scale of coordinated suppression. The program formalized what local police had long practiced: the surveillance, harassment, and violent suppression of any group challenging state power. Operating under the explicit mandate to “disrupt, misdirect, discredit or otherwise neutralize” liberation movements of the 1950s and 1960s, COINTELPRO demonstrated how law enforcement’s true role extends far beyond crime prevention into active political repression. [53] The program empowered both federal agents and local police to deploy a comprehensive arsenal of repressive tactics: infiltrating organizations to gather intelligence and sow discord, conducting legal harassment through spurious arrests, launching disinformation campaigns to discredit leaders, and employing extralegal violence—including assassination—to “neutralize” movement leadership. This coordination between federal and local law enforcement created a multilayered system of repression. Local police provided the boots on the ground for surveillance and harassment, while the FBI supplied intelligence, resources, and political cover for escalating violence against activists.

The American Indian Movement (AIM) faced this brutal coordination firsthand, exemplified by Anna Mae Aquash’s murder—shot and left at the bottom of a cliff, one of many Indigenous activists whose deaths went conspicuously uninvestigated by both local and federal law enforcement. Leonard Peltier’s ongoing incarceration, as America’s longest-held Indigenous political prisoner, demonstrates how this police-state machinery transforms activism into criminality. [54] Even advocates of nonviolent resistance were not spared from this police apparatus. Martin Luther King Jr., despite his peaceful approach, faced relentless surveillance and harassment from both local police departments and the FBI, including attempts to discredit him through personal attacks and anonymous letters encouraging suicide. [55] This targeting reveals how police at all levels view any challenge to state power—violent or nonviolent—as a threat requiring elimination. While COINTELPRO officially ended, its methods set the blueprint for how modern police continue to respond to social justice movements, establishing patterns of surveillance, infiltration, and violence that persist in law enforcement’s approach to political dissent. Today’s police departments, equipped with military-grade surveillance technology and weaponry, carry forward this legacy of political repression, demonstrating how policing consistently functions as the frontline force in suppressing challenges to state power and preserving America’s mythology of democratic freedom. [56] The First Amendment protects the right to protest, but, despite being largely peaceful, contemporary protests and activism events are heavily policed areas.

Ironically, LGBTQ+ Pride marches began as commemoration of an uprising against police violence and are now met with steady police presence, despite “increasingly high rates of LGBTQ+ victimization and criminalization by law enforcement.” [57] At many protests, from Pride, to Black Lives Matter, to Palestine, to Day of Mourning, the police are not only present, they are also armed with riot gear, tear gas, pepper spray, and rubber bullets. There are countless instances of police attacking and violently arresting protesters, such as in 2020 when police fractured an elderly person’s skull. [58] Ironically, again, the police’s aggressive reactions to Black Lives Matter protests “[served] as yet another example of the very police violence that protestors were calling to end.” [59] Pro-Palestinian protesters faced similar treatment after Israel’s sharp escalation of Palestinian genocide in 2023 and 2024, with many reporting serious injuries inflicted by the police. [60] The insistence of law enforcement to meet protests with sophisticated violence, inherited from programs such as COINTELPRO and borrowed from militaries around the world, calls into question the illusion of the police as protectors of safety.

“Copaganda” and Police Immunity

While critical perspectives on policing emerge from documented histories of oppression, a counter-narrative perspective works to present police as society’s guardians. This carefully constructed image finds perhaps its most explicit expression in the “Blue Lives Matter” movement, which emerged as a direct attempt to silence and discredit Black Lives Matter activism. [64] From “Law & Order” to “COPS” to “Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” police procedurals and reality shows flood television networks with sanitized, heroic and humorous depictions of law enforcement that normalize police violence and surveillance while erasing the devastating impact on communities—creating generation after generation of viewers who internalize the myth of the righteous cop. [65]

Supporters of Blue Lives Matter argue that police officers risk their lives daily in service of public safety, portraying them as selfless protectors of community welfare. However, this narrative deliberately obscures several crucial realities: the fundamental power disparity between police and civilians rests in the fact that officers carry state-sanctioned weapons and enjoy near-total immunity for their actions, protected by the very state apparatus they serve. Being a police officer is not among the top ten most dangerous jobs in America (with occupations like logging, fishing, and delivery driving claiming more lives), and police spend only a small percentage of their time responding to violent crime. [66] Their primary function, both historically and presently, has been protecting property and maintaining social control through violence and brutality rather than protecting human life—a reality evidenced by their daily practices of harassment, intimidation, and force against marginalized communities. Organizations like Blue Lives NY, with their mission “to help Law Enforcement Officers and their families during their time of need,” work to position police officers as heroes and essential societal aids—a narrative that again, obscures the institution’s roots in Indigenous relocation and slave patrols while actively undermines efforts to address police violence. [67] The “Blue Lives Matter” movement particularly demonstrates how pro-police rhetoric functions to deflect accountability, dismiss valid criticism, and justify continued violence against marginalized communities by framing police as victims rather than perpetrators of systemic violence. This false equivalency between a chosen profession and racial identity serves to trivialize the lived experiences of those who face actual systemic oppression while providing cover for continued police brutality.

Modern “copaganda” has evolved into a sophisticated multimedia campaign operating across various platforms. Social media feeds fill with carefully curated TikToks showing police officers dancing with civilians—their weapons conveniently relegated to the background of these manufactured moments of connection. Commercial advertising, exemplified by Kendall Jenner’s notorious Pepsi campaign, attempts to romanticize police-protester relations through superficial gestures of reconciliation, trivializing the real violence and trauma inflicted by law enforcement on protest movements. Perhaps most insidiously, this propaganda targets children through seemingly innocent entertainment. Disney’s Zootopia (2016) presents itself as a progressive parable about prejudice, yet functions as sophisticated copaganda for young audiences. [68] The film’s narrative, following Judy Hopps as the first rabbit police officer in a metropolis where predator and prey animals coexist, codes predators as people of color and prey as white society.

While ostensibly addressing discrimination, the story culminates not in systemic change but in the conversion of Nick Wilde, a skeptical fox, into a believer in law enforcement—a classic propaganda narrative arc that serves to normalize police authority and delegitimize systemic critique. As Erin Corbett defines it, copaganda encompasses media’s deliberate creation of positive police depictions across multiple channels: from curated social media posts and uncritical journalism to community outreach events designed to position police as indispensable community guardians. [70] This messaging proves most effective when targeting children, embedding pro-police sentiments early that may make adults more likely to defend police violence than confront the documented realities of systemic racism and brutality.

Abolition

“Nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them.”

Assata Shakur, Assata: An Autobiography [71]

When George Floyd was murdered by police officer Derek Chauvin in 2020, many dismissed Chauvin’s behavior as a “rogue cop who had abandoned his training.” [72] This view attempts to distance “bad apples” like Chauvin from the overall “good” system of law enforcement. The “bad apples” metaphor neglects to address how the police systematically enable and encourage violence, especially against Black people. In the words of journalist Vann Newkirk, “a system cannot fail those it was never built to protect” [73]. Abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba adds, “When a police officer brutalizes a black person, he is doing what he sees as his job.” [74] Thus, the system is not broken, but operating exactly as intended: to protect those in power. [75], [76] This mindset provides an ideological basis for abolition as opposed to reform.

One popular mode of reform is the introduction of more training for police officers. When Eric Garner was killed by police in 2014, the New York Police Department (NYPD) instituted additional training in use-of-force and deescalation for officers. As Alex Vitale outlines in his book The End of Policing, these trainings do not address the root causes of Garner’s death: the officers’ “casual disregard” of and indifference to Garner’s life, as they ignored his cries for help, and the mindset of “broken-windows policing” that encourages officers to aggressively prosecute minor crimes (Garner was accused of selling loose cigarettes). [77]

After Garner’s death, the federal government, under President Barack Obama, instituted policies of reform for police departments in six different cities, including Minneapolis, where Floyd would later be murdered. The $4.75 million reform project, which was viewed as “groundbreaking”, implemented body cameras, implicit bias training, and practicing mindfulness [78]. This project is one of many initiatives of “procedural justice,” which Vitale says describes most current reform programs. Procedural justice reforms propose that the problems with policing are due to how the law is enforced, and that more training and better police-community relations are needed and will strengthen public trust in police. The most potent effect of procedural justice reform is that the people will feel better about their interactions with the police, even if they end up charged, ticketed, or arrested. Ultimately, these expensive programs sidestep the root of the problem, which lies in policing’s oppressive, violent, racist history. [79]

Another type of reform involves diversity training, with many police departments boasting that their members have undergone training to mitigate implicit bias. This training is typically brief, and research has found that it is unlikely to result in lasting changes in officers’ behaviors. [80] Similarly targeting the idea of diversity, another component of reform involves hiring more diverse police officers. Vitale writes that there is little evidence that more diverse police forces are less racist and violent, and in fact they are “just as likely to have systematic problems with excessive use of force.” [81]

Chauvin’s murder of Floyd exposes one of many examples of reform’s failure: in the Minneapolis Police Department, the implementation of procedural justice initiatives did nothing to prevent Chauvin’s actions. As abolitionists point out, many cities, such as Minneapolis, have undergone police reform, and yet police brutality remains more a problem than ever. A graphic from abolitionist organization Critical Resistance illustrates how many police reforms are not just ineffective, they actually work against principles of abolition by allocating more money and resources to the police, “without altering the racist and violent structure of policing.” [82], [83] Furthermore, researcher Charlotte Rosen argues that reform has not only not worked, it actually has “helped expand and normalize police presence Black urban communities.” [84] Liberal reform has attempted to root out the racism within policing, “rather than confronting how the very function and operation of policing historically operated to uphold racial hierarchies, suppress dissent, and protect capital.” [85]

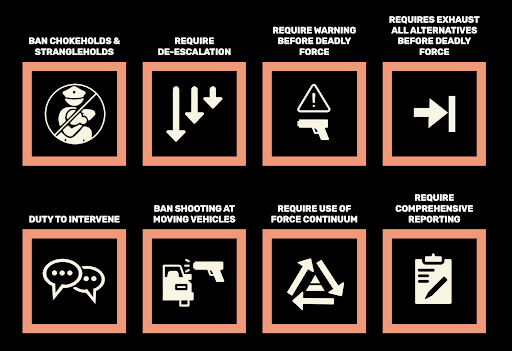

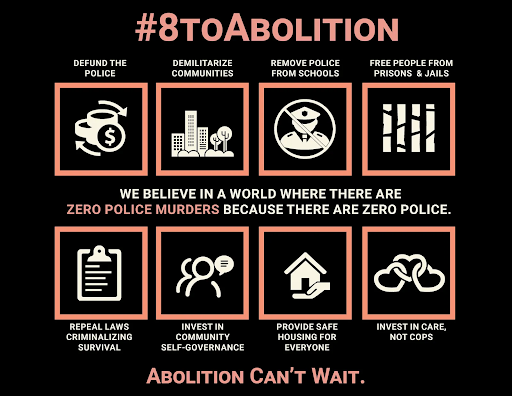

The question of reform versus abolition gained more mainstream attention following the death of Floyd. A set of proposed reforms tagged with #8cantwait spread across social media and included demands such as banning the use of chokeholds and shooting at moving vehicles, requiring deescalation and adherence to a use-of-force continuum, and requiring comprehensive reporting. [86] An abolitionist counter to this campaign, #8toabolition, pushed for broader goals: defunding the police, removing police from schools, and demilitarizing communities. The #8toabolition demands also include ensuring safe housing for all and freeing people from prison and jail. [87] These objectives may not seem directly related to policing, but function within the idea that abolition must be intersectional. Although “abolition” has traditionally referred to the movement to end chattel slavery, the term has evolved to describe dismantling of all patriarchal/racist/heteronormative/capitalist systems, including the prison industrial complex and the police.

While the concepts of abolition are inherently deconstructive, abolitionists emphasize that abolition is a process not of destroying, but of world-building. [90] Robyn Maynard writes that “world-ending and world-making can occur, are occurring, have always occurred, simultaneously,” and in fact, not all “world-endings” are bad. [91] Maynard does not fear the apocalypse, rather, she welcomes the toppling of the murderous, racist, capitalist, white-supremacist world, and is determined to build a better one thereafter. She also notes that, as a result of being “globally positioned as ‘first to die’ within the climate crisis,” Black and Indigenous communities are “already post-apocalyptic experts and can best imagine worlds beyond our current realities.” [92] These communities, with rich “traditions of radicalism, resistance, and co-resistance,” have been world-building for a very long time, and will continue to spearhead abolitionist efforts to create a better future. [93]

Our group chose to define policing within its foundational historical context as an institution rooted in and continuing to uphold colonial power structures and racial hierarchies. This system was deliberately established to protect colonial settlements while enforcing state-sanctioned brutality that continues to inflict disproportionate harm on BIPOC communities. Understanding policing’s deep roots in colonial control—from Indian Agents forcibly confining Indigenous peoples to reservations, to slave patrols maintaining chattel slavery—is essential for contextualizing both systemic oppression and contemporary abolition movements. Divorcing policing from its brutal past is fundamentally ahistorical, as the modern institution still fulfills its original function: maintaining territorial and political control through force. The disproportionate death toll and devastation inflicted on the very people police claim to “protect and serve” are not system failures, but proof the institution operates exactly as designed. This is precisely why we advocate for abolition—the system cannot be reformed because it is not broken; it continues to fulfill its intended purpose.

Contributors

Sam Jonas, Oliver Bello, Amal Mohamed

Footnotes

- “Photos: Powerful Images Show…”

- Lepore, “The Invention of the Police”

- Lepore

- Lepore

- Parks and Kirby, “The Function of the Police Force…”

- Salimbene,“The Genesis of Formal Police Agency Creation in U.S. Cities…”

- Oxford Dictionaries, “Police”

- Oxford Dictionaries

- Thusi, “Blue Lives & The Permanence of Racism”

- Washington Post, “The origins of policing in America…”

- Ali, “The Slave Patrols of the Past…”

- Lepore, “The Invention of the Police”

- O’Neil, “The Indian Reservation System”

- Dippier, “The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy.”

- Salimbene,“The Genesis of Formal Police Agency Creation in U.S. Cities…”

- Estes et al., “Introduction: I Can’t Fucking Breathe!”

- “The Origins of Modern Day Policing,” NAACP

- Hassonjee, “Militarization of Police Fails…”

- Lepore, “The Invention of the Police”

- Bassett, “A History of US Police Violence”

- Friedman and Gillooly, “Police Militarization…”

- Ray, “How 9/11 Helped to Militarize American Law Enforcement”

- “Deadly Exchange in Focus: Participant Profiles”

- “Matt Apuzzo, Adam Goldman, Eileen Sullivan and Chris Hawley…”

- “GILEE Home Page”

- “Deadly Exchange Research Report”

- Hawari, “‘The Skunk’: Another Israeli Weapon…”

- Hawari

- Slisco, “Arizona Sheriff Candidate Proposes…”

- Elia, “Seattle Vowed to Demilitarize…”

- Vitale, The End of Policing, 9

- Gay, “A Small Needful Fact”

- Gay

- Ramos, “Protest and Remembrance: Chicanx Artists…”

- Originol, Justice for Our Lives

- Shea, “MFA Acquires Major Work…”

- Blay, “A Baker’s Dozen: 14 Works…”

- Shea, “MFA Acquires Major Work…”

- Shea

- Walter, “George Jackson: Black Revolutionary”

- Malott et al, “George Jackson’s ‘Blood in My Eye:’ A Critical Appraisal,” 15

- Jackson, “Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson” 253

- Jackson

- Jackson, “Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson,” 223

- “George Jackson’s Legacy”

- Peltier, “Prison Writings: My Life is my Sun Dance,” 66

- Rajguru and Wood, “The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense”

- Jackson, “Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson,” 18

- drsonnet

- Levinson, “Aaron Bushnell Told Us Why…”

- Abu-Jamal, “Rights Humane”

- “COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI…”

- “COINTELPRO: International Leonard Peltier…”

- “COINTELPRO: International Leonard Peltier…”

- Hoban, “‘Discredit, Disrupt, and Destroy’: FBI…”

- Lepore, “The Invention of the Police”

- Girardi, “It’s Easy to Mistrust Police…”

- Jones and Kishi, “Demonstrations and Political Violence in America…”

- Kajeepeta and Johnson, “Police and Protests: The Inequity of Police…”

- Sheets et al., “Police Report No Serious Injuries…”

- “Police Arrest Dozens of Pro-Palestinian Protesters…”

- Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975

- Corbett, “Copaganda: A Look into the Subversive…”

- Thusi, “Blue Lives & The Permanence of Racism”

- Rackstraw, “When Reality TV Creates Reality…”

- Asher & Horwitz,“How Do the Police Actually Spend Their Time?”

- “Our Mission”

- Zootopia

- “Zootopia”

- Corbett, “Copaganda: A Look into the Subversive…”

- Taylor, “The Emerging Movement for for Police…”

- Shakur, Assata: An Autobiography, 190

- Rothman, “That ‘A System Cannot Fail…’ Quote…”

- Kaba, “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police.”

- Parks and Kirby, “The Function of the Police Force…”

- Sultan and Herskind, “What is Abolition, and Why Do…”

- Vitale, The End of Policing, 5-6

- Siegel, “‘Starve the Beast’: A Q&A…”

- Vitale, The End of Policing, 13-15

- “Commonly used police diversity training…”

- Vitale, The End of Policing, 12

- Rosen, “Abolition or Bust: Liberal Police…”

- “Reformist Reforms vs. Abolitionist Steps”

- Rosen, “Abolition or Bust: Liberal Police…”

- Rosen

- “8 Can’t Wait”

- Rosen, “Abolition or Bust: Liberal Police…”

- “8 Can’t Wait”

- 8 to abolition

- Sultan and Herskind, “What is Abolition, and Why Do…”

- Maynard and Simpson, “On Letter-Writing, Commune, and the End of (This) World, in Rehearsals for Living, 20.

- Maynard and Simpson, “On Letter-Writing, Commune, and the End of (This) World, in Rehearsals for Living, 21.

- Maynard and Simpson

Bibliography

“8 Can’t Wait.” 8 Can’t Wait. Accessed December 17, 2024. https://8cantwait.org/.

8 to abolition. 2020. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/8-to-abolition-abolish-police-keep-us-safe-op-ed.

Abu-Jamal, Mumia. “Rights Humane.” Art and the Freedom Struggle, The Works of Mumia Abu-Jamal. Brown University Library, 1999.

Ali, Charlotte Zobeir. “The Slave Patrols of the Past Are Now the US Police.” Medium, August 27, 2020. https://medium.com/la-biblioth%C3%A8que/the-slave-patrols-of-the-past-are-now-the-us-police-9664a5c7c547.

Asher, Jeff, and Ben Horwitz. “How Do the Police Actually Spend Their Time?” The New York Times, June 19, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/19/upshot/unrest-police-time-violent-crime.html

Bassett, Mary T, “A History of US Police Violence.” The Lancet, 2021. Volume 397, Issue 10289, Pages 2039-2040, ISSN 0140-6736, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01153-3. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673621011533)

The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e0bWTh74m6c&t=2091s.

Blay, Christopher. “A Baker’s Dozen: 14 Works of Art about Protest and Police Brutality [1963 – 2018].” Glasstire, June 21, 2020. https://glasstire.com/2020/06/19/a-bakers-dozen-14-works-of-art-about-protest-and-police-brutality-1963-2018/.

“COINTELPRO.” International Leonard Peltier Defense Committee. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.whoisleonardpeltier.info/home/background/cointelpro/.

“COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement.” Zinn Education Project, October 2, 2024. https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/cointelpro-teaching-fbis-war-black-freedom-movement/.

“Commonly used police diversity training unlikely to change officers’ behavior, study finds.” Psychology & Psychiatry Journal, February 25, 2023, 99. Gale Academic OneFile (accessed December 17, 2024). https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.library.tufts.edu/apps/doc/A737824818/AONE?u=mlin_m_tufts&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=5f48be5c.

Corbett, Erin. “Copaganda: A Look into the Subversive Ways Police Ask for Sympathy.” Why Copaganda Is A Dangerous Police Sympathy Tactic, July 1, 2020. https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2020/07/9887229/copaganda-police-propaganda-protests-meaning.

“Deadly Exchange in Focus: Participant Profiles.” Deadly Exchange. Accessed December 18, 2024. https://deadlyexchange.org/participant-profiles/.

“Deadly Exchange Research Report.” Deadly Exchange. Accessed December 18, 2024. https://deadlyexchange.org/deadly-exchange-research-report/.

Dippier, Brian W. “The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy.” 1991. E93 . D58 1991

“The Dragon Speaks: ‘When The Prison Doors Are Opened, The Real Dragon Will Come.’” The Black Panther, Black Community News Service, 1991. https://99books.freedomarchives.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/513.BPP_paper_GJ.8.28.71.pdf

drsonnet. 2024. The Southerner. https://www.shsoutherner.net/features/2024/05/15/aaron-bushnell-the-consequences-of-american-complacency/.

Elia, Nada. “Seattle Vowed to Demilitarize the Police, but Rejected Legislation to End Trainings in Israel Following ADL Lobbying.” Mondoweiss, March 31, 2022. https://mondoweiss.net/2022/03/seattle-vowed-to-demilitarize-the-police-but-rejected-legislation-to-end-trainings-in-israel-following-adl-lobbying/.

Estes, Nick (Lower Brule Sioux), Yazzie, Melanie (Diné), Denetdale, Jennifer Nez (Diné), Correia, David. “Introduction: I Can’t Fucking Breathe!” in Red Nation Rising: From Bordertown Violence to Native Liberation. Oakland: PM Press, 2021, 1-18

Friedman, Barry, and Jessica Gillooly. “Police Militarization: A 1033 Program Analysis.” The Policing Project, December 20, 2021. https://www.policingproject.org/news-main/2021/12/16/what-should-be-done-about-militarization-and-the-1033nbspprogram.

Gay, Ross. “A Small Needful Fact.” Poets.org, February 2, 2021. https://poets.org/poem/small-needful-fact.

“George Jackson’s Legacy.” Freedom Archives. https://99books.freedomarchives.org/archival-materials/.

“GILEE Home Page.” Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange (GILEE). Accessed December 18, 2024. https://gilee.gsu.edu/.

Girardi, Rachele. “‘It’s Easy to Mistrust Police When They Keep on Killing Us’: A Queer Exploration of Police Violence and LGBTQ+ Victimization.” Journal of Gender Studies 31, no. 7 (September 14, 2021): 852–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1979481.

Godes, Andrew. “Aaron Bushnell: The Consequences of American Complacency.” The Southerner, May 15, 2024. https://www.shsoutherner.net/features/2024/05/15/aaron-bushnell-the-consequences-of-american-complacency/.

Hassonjee, Arva. “Militarization of Police Fails to Enhance Safety, May Harm Police Reputation.” Princeton University, August 21, 2018. https://www.princeton.edu/news/2018/08/21/militarization-police-fails-enhance-safety-may-harm-police-reputation.

Hawari, Yara. “‘The Skunk’: Another Israeli Weapon for Collective Punishment.” Al Jazeera, May 15, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/5/12/the-skunk-another-israeli-weapon-for-collective-punishment.

Hoban, Virgie. “‘Discredit, Disrupt, and Destroy’: FBI Records Acquired by the Library Reveal Violent Surveillance of Black Leaders, Civil Rights Organizations.” UC Berkeley Library, January 18, 2021. https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/about/news/fbi.

Jackson, George. Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson. Coward-McCann, 1970.

Jones, Sam, and Roudabeh Kishi. “Demonstrations and Political Violence in America: New Data for Summer 2020.” ACLED, April 2, 2024. https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in-america-new-data-for-summer-2020/.

Kaba, Mariame. “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police.” The New York Times, June 12, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/12/opinion/sunday/floyd-abolish-defund-police.html.

Kajeepeta, Sandhya, and Daniel K.N. Johnson. “Police and Protests: The Inequity of Police Responses to Racial Justices Demonstrations.” The Thurgood Marshall Institute at LDF, November 17, 2023. https://tminstituteldf.org/police-and-protests-the-inequity-of-police-responses-to-racial-justices-demonstrations/.

Lepore, Jill. “The Invention of the Police,” The New Yorker, July 13, 2020.

Levinson, Nan. “Aaron Bushnell Told Us Why He Self-Immolated-Why Didn’t We Believe Him?” The Nation, July 17, 2024. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/aaron-bushnell-self-immolate-palestine-mental-health/.

Malott, Curry, Randall Scott, and Elgin Bailey. “George Jackson’s ‘Blood in My Eye:’ A Critical Appraisal – Liberation School.” George Jackson’s “Blood in my eye:” A critical appraisal, February 1, 2022. https://www.liberationschool.org/george-jackson-blood-in-my-eye/.

“Matt Apuzzo, Adam Goldman, Eileen Sullivan and Chris Hawley of the Associated Press.” The Pulitzer Prizes, n.d. https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/matt-apuzzo-adam-goldman-eileen-sullivan-and-chris-hawley.

Maynard, Robyn, and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. “On Letter Writing, Commune, and the End of (This) World.” Essay. In Rehearsals for Living, 12–32. Haymarket Books, 2022.

O’Neil, Terry. “The Indian Reservation System.” 2002, E93 .I3827 2002

Originol, Oree. Justice For Our Lives. 2014. Smithsonian American Art Museum. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/justice-our-lives-117003.

“The Origins of Modern Day Policing.” NAACP, December 3, 2021. https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/origins-modern-day-policing.

“Our Mission.” Blue Lives Matter NYC. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://bluelivesmatternyc.org/pages/frontpage.

Oxford Dictionaries, “Police.” In The Oxford Essential Dictionary of the U.S. Military. : Oxford University Press, 2001. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199891580.001.0001/acref-9780199891580-e-6183.

Parks, Natalie, and Beverly Kirby. “The Function of the Police Force: A Behavior-Analytic Review of the History of How Policing in America Came to Be.” Behavior Analysis in Practice 15, no. 4 (May 12, 2021): 1205–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00568-6.

Peltier, Leonard. Prison Writings: My Life is my Sun Dance. Edited by Harvey Arden. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

“Photos: Powerful Images Show Clashes with Police, Demonstrators during Protests over George Floyd’s Death.” ABC7 Los Angeles, May 31, 2020. https://abc7.com/george-floyd-protests-photos-protest-pictures/6222890/.

“Police Arrest Dozens of Pro-Palestinian Protesters at Columbia, Including Congresswoman’s Daughter.” Associated Press, April 19, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/columbia-protests-israel-palestinian-hirsi-cd80372939c7c08a40346e8b7d546da1.

Rackstraw, Emma. “When Reality TV Creates Reality: How ‘Copaganda’ Affects Police, Communities, and Viewers.” October 30, 2023. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4592803 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4592803

Rajguru, Nutan, and Adrian Wood. “The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.” Socialist Alternative. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.socialistalternative.org/panther-black-rebellion/the-black-panther-party-for-self-defense/.

Ramos, E. Carmen. “Protest and Remembrance: Chicanx Artists Confront Police Brutality.” Smithsonian American Art Museum, May 14, 2021. https://americanart.si.edu/blog/chicanx-art-police-brutality.

Ray, Rashawn, Suddler, Carl, David Harshbarger Andre M. Perry, Howard Henderson, and Manann Donoghoe Hanna Love. “How 9/11 Helped to Militarize American Law Enforcement.” Brookings, January 23, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-9-11-helped-to-militarize-american-law-enforcement/#:~:text=Federal%20programs%2C%20such%20as%20the,equipment%20to%20police%20for%20free.

“Reformist Reforms vs. Abolitionist Steps in Policing.” Critical Resistance, 2020. https://criticalresistance.org/resources/reformist-reforms-vs-abolitionist-steps-in-policing/.

Rodney, Walter. “George Jackson: Black Revolutionary.” Hood Communist, November 1971, published February 24, 2022. https://hoodcommunist.org/2022/02/24/george-jackson-black-revolutionary/

Rosen, Charlotte. “Abolition or Bust: Liberal Police Reform as an Engine of Carceral Violence.” The Abusable Past, June 25, 2020. https://abusablepast.org/abolition-or-bust-liberal-police-reform-as-an-engine-of-carceral-violence/.

Rothman, Lily. “That ‘A System Cannot Fail…’ Quote? It’s Not From W.E.B. DuBois.” Time, November 25, 2014. https://time.com/3604241/w-e-b-dubois-quote-ferguson/.

Salimbene, Nicholas. “The Genesis of Formal Police Agency Creation in U.S. Cities: Police Practice and Research.” 2021, 22:1, 805-816, DOI: 10.1080/15614263.2019.1700118

Shakur, Assata. Assata: An Autobiography. Zed Books, 1987.

Shea, Andrea. “MFA Acquires Major Work Artist Dana Chandler Created after Black Panther Fred Hampton’s Assassination.” WBUR News, April 7, 2021. https://www.wbur.org/news/2021/04/07/mfa-dana-chandler-black-panther-fred-hampton-door.

Sheets, Connor, Richard Winton, Jason Armond, Safi Nazzal, and Brittny Mejia. “Police Report No Serious Injuries. but Scenes from inside UCLA Camp, Protesters Tell a Different Story.” Los Angeles Times, May 3, 2024. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-05-03/injuries-during-clearing-of-ucla-encampment.

Siegel, Zachary. “‘Starve the Beast’: A Q&A with Alex S. Vitale on Defunding the Police.” The Nation, June 24, 2020. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/alex-vitale-defund-police-interview/.

Slisco, Aila. “Arizona Sheriff Candidate Proposes Using ‘Skunk Water’ to Thwart Protesters.” Newsweek, October 20, 2020. https://www.newsweek.com/arizona-sheriff-candidate-proposes-using-skunk-water-thwart-protesters-1540438.

Sultan, Reina, and Micah Herskind. “What Is Abolition, and Why Do We Need It?” Princeton University, July 28, 2020. https://aas.princeton.edu/news/what-abolition-and-why-do-we-need-it.

Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. “The Emerging Movement for Police and Prison Abolition.” The New Yorker, May 7, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-emerging-movement-for-police-and-prison-abolition.

Thusi, India. “Blue Lives & The Permanence of Racism.” Cornell Law Review, March 3, 2020. https://www.cornelllawreview.org/2020/03/03/blue-lives-the-permanence-of-racism/.

Vitale, Alex S. The end of policing. London: Verso, 2021.

Zootopia. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Animations, 2016.

“Zootopia.” Disney Movies, March 4, 2016. https://movies.disney.com/zootopia