Queerness

Definition

Disclaimer: Due to this term’s complex and nuanced history, not everyone who falls under the technical definition of queerness will choose to identify as such.

Modern Definition: Describing one who identifies with a sexual orientation or gender identity beyond the bounds of cisgender and/or heterosexual expectations; previously used as a slur but has since been reclaimed by many.

Explicit meaning: “Differing in some way from what is usual or normal: Odd, Strange, Weird”

Merriam-Webster. “Queer Adjective.” Merriam-Webster. Accessed December 4, 2022.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/queerness.

Discussion

Evolution of the Term

Video. YouTube. Posted by Them, 2018. Accessed December 4, 2022.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UpE0u9Dx_24.

When discussing the history of “queerness”, it is crucial to make a distinction between the evolution of the community which now identifies with the term and its current meaning, and the evolution of the word itself––one iteration among many that serve the purpose of describing that which is outside the cis-heteropatriarchal norm. Here the word itself will only be introduced briefly to provide context for its relevance to the community it describes, while the evolution of the community and its relationship to this and similar terms will be discussed in more depth.

As a word, “queer” has been used for centuries to describe “strange, odd, or suspicious” people or things.[1] This usage primarily described a quality or behavior rather than identity or relationality, only coming to its modern derogatory meaning in 1894 in the smear campaign against Oscar Wilde run by John Douglas after discovering his son’s affair with Wilde. While this still centered “queerness” around behavior rather than identity, it ties that behavior to a relationship with colonially imposed gender binary and heterosexuality, introducing the word’s affiliation with a conceptual and behavioral deviation from societal norms. The term was thus used as a form of violence to enforce the colonial binary, hurled primarily at those with intentional or unintentional non-heterosexual identity markers,[2] but also applicable to anyone deemed a threat to the continuation of a heteropatriarchal system. This creates the usage of “queer” as a noun, solidifying its place in mainstream culture as a homophobic slur.

Though the cultural implications of AIDS reach far beyond changes in vocabulary and will be discussed further later, it also introduced a key change to the word “queer” as reclamation of the slur began to gain traction through the widespread defiance and community formation out of necessity as a result of the epidemic’s devastating impacts. Over time, the reclamation of “queer” and “queerness” as self-identifying labels has evolved from a radical stance to an umbrella term, gaining normality and public acceptance in the same manner as the LGBT community did: by centering the most powerful and catering its intentions/meaning to be least disruptive to existing social and political structures, often resulting in erasure of those who are not white, cis, gay men.[3]

The usage of “queer” and “queerness” as fundamentally in conflict with a colonial heteropatriarchal binary is still present within more radical circles, but it is now the sentiment of dissent and unbelonging which goes undiscussed in mainstream media, publicly portraying common usage of the word as empowerment while allowing it to coexist with the structures which produce anti-queer slurs in the first place.

Construction of Queerness

Queerness is often defined in terms of what it rejects: a heteropatriarchal model centering cisgender, heterosexual individuals as members of nuclear family units. By placing queerness relative to this system, patterns of value and worth based upon gender identity and sexual orientation begin to emerge.

In his 1949 Social Structure, anthropologist George Peter Murdock defines the nuclear family as “includ[ing] adults of both sexes, at least two of whom maintain a socially approved sexual relationship, and one or more children, own or adopted, of the sexually cohabiting adults.”[4] Some scholars have since expanded the scope of the nuclear family model to include adults of the same sex,[5] yet Murdock’s expectation of families to balance and control “the sexual, the economic, the reproductive, and the educational”[6] remains constant. These categories are thought to control the value of a family unit, thereby tying the value of an individual to their ability to positively influence these “fundamental”[7] functions within the family; to reject the nuclear family is to risk one’s perceived value in society.

Debrocke. Family Portrait, C.1950s. Photograph. Fine Art America. November 1,

2015. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://fineartamerica.com/featured/

family-portrait-c1950s-debrockeclassicstock.html.

This is not to say that all societies measure value in the same way. For instance, the change in gender roles can be measured in many Indigenous communities in Canada, when the Indian Act of 1976 placed men at the head of the household. Although most tribes were matrilineal, the Canadian government gave Indigenous men priority for land and property ownership.[8] Native studies theorist Andrea Smith argues that “when colonists first came to the Americas, they saw the necessity of instilling patriarchy in Native communities because they realized that indigenous peoples would not accept colonial domination if their own indigenous societies were not structured on the basis of social hierarchy.”[9] By reinforcing the gender binary, these colonial forces attempted to restructure Indigenous societies to fit within their own heteropatriarchal value systems.

“Queerness and indigeneity not intersecting quietly

white queers policing your existence

indigenous blood telling you that you’re

a new generation problem.”

Twist, Arielle. Disintegrate/dissociate : Poems. Vancouver, BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019, 68-9.

This construction of the nuclear family serves to reinforce power structures and define the worth of individuals. While this can be done through legislation, it often occurs less formally, through subtle (or not-so-subtle) exclusions of those who do not conform to heteropatriarchal values. As of 2022, six states explicitly prohibit the positive or neutral discussion of LGBTQ-inclusive topics in school sex education.[10] Even in states that do not have laws forbidding educators from discussing queerness in sex education, queer students often feel excluded or ashamed. A 2017 study concluded that sex education is particularly unhelpful to sexual minorities, and may even be detrimental to their emotional well-being due to the perpetuation of heteronormativity in most sex education curricula. The study states, “Sex education also reportedly contributed to sexual hesitance, sexual violence, and risky sexual behaviors…inclusivity in curricula could lead to various improved outcomes for [sexual minorities], such as safe sex, a sense of community, identity confidence, healthy relationships, and resilience.”[11] Heteronormativity is so strongly integrated into modern society; the assumption that students only need sex education that applies to heterosexual relationships derives largely from the assumption that people are heterosexual unless proven otherwise.

The US Queer Experience

Throughout the history of queer experience in the United States, one can note a pattern of acceptance and resistance that has intermittently been flowing in and out of society. From the 1920s to present day, the experiences for queer individuals have both struggled and flourished.

Beginning in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 30s, the queer experience was accepted through the vast cultural bloom in the nightclubs of New York City. Harlem drag balls were prevalent, and “the ballroom scene…[expressed] it’s allegiance to the black, queer community [through its] narrative of art, self-expression, freedom and fluidity”.[12]

Posted by NowThis News, 2021. Accessed December 4, 2022.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DM7Qa_Xb8u0&t=11s.

Yet, resistance soon followed this embrace with the beginning of The Great Depression when many blamed the period of the vast cultural bloom for the economic downfall of the country, thus leading to oppression of the queer community.[13]

Later, in 1969 during The Stonewall Riots, which “ignited the gay liberation movement”,[14] this notion of acceptance resurfaced within the queer community. Although due to the very name of the event, “riot”, resistance was inherently involved, this paramount event sparked much opportunity for queer affirmation as it illustrated how as a community,[15] they could combat the resistance.

by History, 2018. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=Q9wdMJmuBlA.

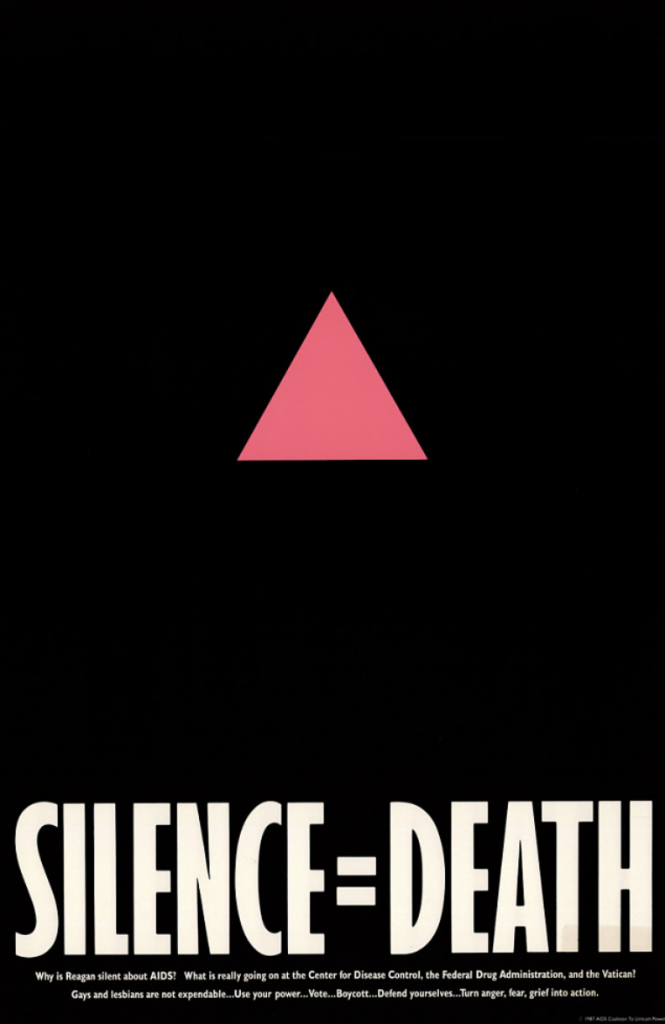

Although in the later half of the 20th century queer expression was not entirely hidden, resistance increased in the 1980s with the AIDS epidemic. Queer individuals faced hostility in the form of “social death”[16] due to its rapid spread amongst the gay male population.[17] Once again however, this struggle forged acceptance as “the AIDS epidemic brought people of differing identities together: lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals [to form] what we know today as the LGBTQ community”.[18]

‘Why AIDS is likely to remain largely a gay disease.’ Illustration by Lewis Calver for Discover, December 1985. Paula Treichler, ‘AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse: An Epidemic of Signification.’ October 43 (1987), 38.

AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. Silence = Death, 1987, National Museum of American History. Accessed November 13, 2022. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1051178.

In the 2000s, queer experiences have been increasingly accepted by society as seen by the legalizing of same-sex marriage in 2015,[20] as well as in mainstream pop culture like music by Lil Nas X, RuPaul’s Drag Race, and same-sex couples in movies, TV, and commercials.

Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sBFH0Tz9epY.

Nevertheless, the queer community is still actively fighting resistance. In the few years after 2015 there have been shootings targeted at queer communities, like the Pulse Nightclub in 2016.[21] Even, presently in 2022, Florida’s Don’t Say Gay law is perpetuating this ever-lingering resistance towards queer individuals.

Thus, one can note that in the United States throughout the past 100 years how the queer community has faced constant bouts of adoption and opposition. Nevertheless, they continue to ensure that their community prevails and others have the space to explore their identities.

Supplementary Media

Various forms of art and media have long articulated the lived queer experience in ways inaccessible to formal academic writings. The following sources are a few examples among the many ways queer artists have communicated their conceptualization of queerness and how it manifests in their lives.

Bikini Kill. Rebel Girl. Kill Rock Stars, 1993, Accessed November 11, 2022. https://open.spotify.com/track/4hNVjaMGvKgAK41O9tQoNn?si=551cbf17f9d24e3b

“Andrea Gibson – First Love.” Youtube, uploaded by Button Poetry, 2018,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=umMt-AfBNhk. Accessed 8 Nov. 2022.

Toor, Salman. The Bar on East 13th. 2019. Oil Painting. Accessed November 28,

2022. https://www.luhringaugustine.com/artists/salman-toor#tab:thumbnails.

QUAC Collective. “Zine: Queers Under All Conditions #1.” QZAP – Zine Archive. Last modified 2010. Accessed December 11, 2022. https://archive.qzap.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/316.

QUAC is a zine that provides an alternative to “mainstream” LGBT media sources, instead centering queer experiences from a variety of artists primarily in the Orange County, CA area. The variety of media types, identity backgrounds, and articulations of identity in this zine are a strong introduction to the variety of experiences encapsulated by the word “queer”, and therefore is important to include when analyzing what queerness means.

References

Footnotes

[1] Kolker, Z.M., Taylor, P.C. & Galupo, M.P. “As a Sort of Blanket Term”: Qualitative Analysis of Queer Sexual Identity Marking. Sexuality & Culture 24, 1337–1357 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09686-4

[2] Morgan, M. E., & Davis-Delano, L. R. (2016). Heterosexual marking and binary cultural conceptions of sexual orientation. Journal of Bisexuality, 16(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2015.1113906.

[3] Hall, Nicolas, ““We’re here, we’re queer, we will not live in fear!”: A Content Analysis Exploring Gender Disparity in the Public Reappropriation of LGBTQ+ Slurs” (2020). Capstone Showcase. 1. [4] Murdock, George Peter. Social Structure. Toronto, Ontario: Colher-Macmillan Canada, Ltd., 1949, 1.

[5] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “nuclear family.” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 16, 2022.https://www.britannica.com/topic/nuclear-family.

[6] Murdock, Social Structure, 10.

[7] Ibid, 10. [8] Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy.” Feminist Formations 25, no. 1 (2013): 8–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860665, 15. [9] Smith, Andrea. “QUEER THEORY AND NATIVE STUDIES: The Heteronormativity of Settler Colonialism.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16, no. 1–2 (April 1, 2010): 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2009-012, 61.

[10] “Sex Education Laws and State Attacks.” Planned Parenthood Action Fund. Accessed November 26, 2022. https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/issues/sex-education/sex-education-laws-and-state-attacks.

[11] Hobaica, Steven, and Paul Kwon. “‘This Is How You Hetero:’ Sexual Minorities in Heteronormative Sex Education.” American journal of sexuality education 12, no. 4 (2017): 423–450.

[12] Truesdale, Karyl J. “Striking a Pose: A History of House Balls.” CFDA. Last modified August 3, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://cfda.com/news/striking-a-pose-a-history-of-house-balls.

[13] Chauncy, George. “A Gay World, Vibrant and Forgotten.” The New York Times, 26 June 1994 [14] Gioia, Christopher L. “Stonewall: Riot, Rebellion, Activism and Identity an Oral History and Archival Exhibition on the Web.” Order No. 10284225, State University of New York Empire State College, 2017. https://login.ezproxy.library.tufts.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/stonewall-riot-rebellion-activism-identity-oral/docview/1926762544/se-2.

[15] Matzner, Andrew. “Stonewall Riots.” GLBTQ Archives. Accessed November 16, 2022. http://glbtqarchive.com/ssh/stonewall_riots_S.pdf. [16] Wright, Joe, MD. “Only Your Calamity: The Beginnings of Activism by and for People with AIDS.” PubMed Central. Last modified October 2013. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780739/.

[17] Fitzsimons, Tim. “LGBTQ History Month: The Early Days of America’s AIDS Crisis. NBC News. Last modified October 15, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/ lgbtq-history-month-early-days-america-s-aids-crisis-n919701.

[18] Latham, Ashley. “Looking Back: The AIDS Epidemic.” SF LGBT Center. Last modified December 15, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.sfcenter.org/history/looking-back-the-aids-epidemic/.

[19]Florêncio, João. “AIDS: Homophobic and Moralistic Images of 1980s Still Haunt Our View of HIV – That Must Change.” The Conversation. Last modified November 27, 2018. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://theconversation.com/aids-homophobic-and-moralistic-images-of-1980s-still-haunt-our-view-of-hiv-that-must-change-106580. [20] Livesay, Jacob. “When Was Same-Sex Marriage Legalized? A Quick History of an LGBTQ Rights Battle in the U.S.” USA Today. Last modified June 21, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2022/06/21/when-same-sex-marriage-legalized/7628967001/.

[21] Zambelich, Ariel, and Alyson Hurt. “3 Hours in Orlando: Piecing Together an Attack and Its Aftermath.” NPR. Last modified June 26, 2016. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2016/06/16/482322488/orlando-shooting-what-happened-update.

Bibliography

AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. Silence = Death. National Museum of American History. Accessed November 13, 2022. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1051178.

Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy.” Feminist Formations 25, no. 1 (2013): 8–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860665.

Bikini Kill. Rebel Girl. Kill Rock Stars, 1993, Accessed November 11, 2022. https://open.spotify.com/track/4hNVjaMGvKgAK41O9tQoNn?si=551cbf17f9d24e3b

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “nuclear family.” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 16, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/nuclear-family.

Debrocke. Family Portrait, C.1950s. Photograph. Fine Art America. November 1, 2015. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://fineartamerica.com/featured/family-portrait-c1950s-debrockeclassicstock.html.

Fauth, RK. “Queer Appalachia.” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, September 2021. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/156318/queer-appalachia.

Fitzsimons, Tim. “LGBTQ History Month: The Early Days of America’s AIDS Crisis.” NBC News. Last modified October 15, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/lgbtq-history-month-early-days-america-s-aids-crisis-n919701.

Florêncio, João. “AIDS: Homophobic and Moralistic Images of 1980s Still Haunt Our View of HIV – That Must Change.” The Conversation. Last modified November 27, 2018. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://theconversation.com/aids-homophobic-and-moralistic-images-of-1980s-still-haunt-our-view-of-hiv-that-must-change-106580.

Hall, Nicolas, ““We’re here, we’re queer, we will not live in fear!”: A Content Analysis Exploring Gender Disparity in the Public Reappropriation of LGBTQ+ Slurs” (2020). Capstone Showcase. 1.

Hobaica, Steven, and Paul Kwon. “‘This Is How You Hetero:’ Sexual Minorities in Heteronormative Sex Education.” American journal of sexuality education 12, no. 4 (2017): 423–450.

Kolker, Z.M., Taylor, P.C. & Galupo, M.P. “As a Sort of Blanket Term”: Qualitative Analysis of Queer Sexual Identity Marking. Sexuality & Culture 24, 1337–1357 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09686-4

“How the Stonewall Riots Sparked a Movement | History.” Video. YouTube. Posted by History, 2018. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q9wdMJmuBlA.

Latham, Ashley. “Looking Back: The AIDS Epidemic.” SF LGBT Center. Last modified December 15, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.sfcenter.org/history/looking-back-the-aids-epidemic/.

Livesay, Jacob. “When Was Same-Sex Marriage Legalized? A Quick History of an LGBTQ Rights Battle in the U.S.” USA Today. Last modified June 21, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2022/06/21/when-same-sex-marriage-legalized/7628967001/.

Matzner, Andrew. “Stonewall Riots.” GLBTQ Archives. Accessed November 16, 2022. http://glbtqarchive.com/ssh/stonewall_riots_S.pdf.

Merriam-Webster. “Queer Adjective.” Merriam-Webster. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/queerness.

Morgan, M. E., & Davis-Delano, L. R. (2016). Heterosexual marking and binary cultural conceptions of sexual orientation. Journal of Bisexuality, 16(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2015.1113906.

Murdock, George Peter. Social Structure. Toronto, Ontario: Colher-Macmillan Canada, Ltd., 1949.

QUAC Collective. “Zine: Queers Under All Conditions #1.” QZAP – Zine Archive. Last modified 2010. Accessed December 11, 2022. https://archive.qzap.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/316.

“The Queer History of the Harlem Renaissance | Legendary.” Video. YouTube. Posted by NowThis News, 2021. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DM7Qa_Xb8u0&t=11s.

“Queer Representation In Pop Culture.” Video. YouTube. Posted by MSNBC, 2021. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sBFH0Tz9epY.

“Sex Education Laws and State Attacks.” Planned Parenthood Action Fund. Accessed November 26, 2022. https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/issues/sex-education/sex-education-laws-and-state-attacks.

Smith, Andrea. “QUEER THEORY AND NATIVE STUDIES: The Heteronormativity of Settler Colonialism.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16, no. 1–2 (April 1, 2010): 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2009-012.

Toor, Salman. The Bar on East 13th. 2019. Oil Painting. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.luhringaugustine.com/artists/salman-toor#tab:thumbnails.

Truesdale, Karyl J. “Striking a Pose: A History of House Balls.” CFDA. Last modified August 3, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://cfda.com/news/striking-a-pose-a-history-of-house-balls.

“Tyler Ford Explains The History Behind the Word ‘Queer’ | InQueery | them.” Video. YouTube. Posted by Them, 2018. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UpE0u9Dx_24.

Twist, Arielle. Disintegrate/dissociate : Poems. Vancouver, BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019.

Wright, Joe, MD. “Only Your Calamity: The Beginnings of Activism by and for People with AIDS.” PubMed Central. Last modified October 2013. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780739/.

Zambelich, Ariel, and Alyson Hurt. “3 Hours in Orlando: Piecing Together an Attack and Its Aftermath.” NPR. Last modified June 26, 2016. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2016/06/16/482322488/orlando-shooting-what-happened-update.

Contributors

Veronika Coyle, Jacqueline Sastry, and Lux Trevelyan