Today, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) sentenced Radovan Karadzić, the political leader of the Bosnian Serbs through the war (1992 – 1995), when he led them into disgrace by trading legitimate concerns about the character of political life in Bosnia’s post-Yugoslav existence for the pursuit of systematic, group targeted violence against their neighbors.

In anticipation, a friend of mine who survived the Bosnian Serbs assaults against her hometown—and who still searches for the remains of her grandparents, uncle and others who were killed in the attack—shared this poem, by Kenyan-born, Somali poem, Warsan Shire.

later that night/ i held an atlas in my lap/ ran my fingers across the whole/ world/ and whispered/ where does it hurt?

it answered/ everywhere/ everywhere/ everywhere

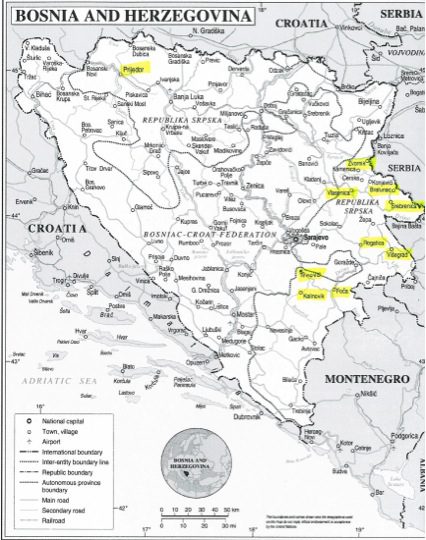

By mid-afternoon at The Hague, her wait and the wait of many others deeply invested in the results of this trial was over. The sentence was issued: forty years in prison. Karadzić was found guilty of genocide for Srebrenica, consistent with the Tribunal’s previous judgments, and multiple counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes, including persecution, extermination, deportation, forcible transfer and murder. The judges did not convict him of genocide for the pattern of violence across areas seized by the Bosnian Serbs at the start of the war in 1992, as named in the indictment: Kljuc, Sanski Most, Bratunac, Foca, Prijedor, Vlasenica and Zvornik. That latter five of these were among the deadliest towns during the entire war, along with Srebrenica, Trnovo, Visegrad, Rogatica, and Kalinovik.

Ten Deadliest Towns during Bosnia War (1992 – 1995).

Source: Map made by Bridget Conley-Zilkic based on analysis of Research and Documentation Center data by Stefan Costalli and Francesco Niccolo Moro. 2012. “Ethnicity and strategy in the Bosnian civil war: Explanations for the severity of violence in Bosnian municipalities.” Journal of Peace Research 49(6): 801 – 815. Appendix.

The decision to convict Karadzić for genocide in Srebrenica reflected the Tribunal’s previous rulings that the highly organized attempt to kill all able-bodied males in this instance met the legal threshold for genocide. The decision not to convict him of genocide for actions elsewhere hinged on what the judges deemed to be a more limited degree of physical destruction—killing— and the decision that genocide was not the only reasonable interpretation of Bosnian Serb actions, hence, there were insufficient grounds to find an intent to destroy (as required for genocide) the Bosnian Muslims.

Legal proceedings are as weak (or as strong) as any of the ‘policy’ tools for responding to such overwhelming violence, each of which is limited by the cold fact that there is no making this right. Nonetheless, weak as response mechanisms are, the effort to use them is even more important than their immediate outputs. History’s long arc forgets the details, bends towards places we cannot know. But its curve is defined by the decisions of thousands to embark in the struggle over what the future will include. Today’s decision by the ICTY will certainly be heatedly debated—and the absence of a conviction for genocide for the violence of 1992 will celebrated or decried, depending on one’s position on the conflict.

Set this aside, just for a moment, and remember all the work of our friends and colleagues in Bosnia and beyond who refuse to accept that the violence was inevitable or natural, but who insist that it was made possible and directed by individuals, who can be held responsible. Only in this recognition is Bosnia’s future possible. So let this be a day when the arc leaned however slightly towards justice, in the rich sense, that is, towards social justice, not merely criminal proceedings.

For my friend, who grew up in the shadow of decisions made by Karadzić and others to respond to uncertainty and fear by provoking violence and organizing for its comprehensive and relentless use to alter the Bosnian map, I hope there is some solace. If not today and if not through this decision, then in the work of rebuilding the country and seeking truth that she and many other brave Bosnians have committed to every day since the war began. May they be the ones who guide the path forward.