Donald Trump’s first foreign trip has been most notable—photo-shoots with dictators around strange glowing orbs aside—for the signing of the largest arms deal in history, worth $110 billion, with Saudi Arabia. Some reports suggest that the total value of arms deals could rise to $350 billion over 10 years. The package certainly includes new items, in particular the Terminal High Altitude Air Defense system (THAAD), as well as warships, tanks and armored personnel carriers, artillery, Patriot missiles, radar systems, and Black Hawk helicopters.

President Obama’s Administration was already the most prolific arms trader in history, approving $278 billion worth of arms sales worldwide, double that of the Bush Administration (although far from all such approvals turn into actual deliveries); but Trump is poised to shatter this dubious record.

One question that comes to mind is, where is Saudi Arabia getting the money from? They already spend over 10% of GDP on the military (and that’s just the official budget—it is likely that arms imports are funded directly from oil revenues, rather than the Defense and Security budget), and are running a large budget deficit. With oil prices still only round $50 a barrel, their $500 billion foreign exchange reserves are fast depleting.

There may be some smoke and mirrors at work here. Some of the arms in the package were already agreed by the Obama Administration, which approved $115 billion of arms sales to Saudi Arabia between 2008 and 2016. The Littoral Combat Ships, tanks, transport aircraft, and some sensors, were already the subject of notifications to Congress. Moreover, insofar as there are new deals, they are not yet finalized—Lockheed Martin’s press release on the subject, for example, talks of letters of offer and acceptance, letters of intent, and memoranda of understanding, but not actual contracts. How many of these deals turn into hard contracts may depend on the price of oil in coming years.

But the smoke and mirrors are themselves part of the point of the exercise—together with the Saudi/UAE $100 million donation to Ivanka Trump’s proposed fund for women entrepreneurs, and the theatrics of Jared Kushner supposedly negotiating a discount for the Saudis with a single phone call to the CEO of Lockheed Martin, the vast sums bandied around serve a political purpose, a very public ‘exchange of gifts’ that helps cement a family-to-family bond between the House of Saud and the Trump-Kushners. Considering the long history of massive corruption in Saudi arms imports, this raises all kinds of red flags in terms of transparency and good governance; although the US Foreign Military Sales process may make actual corruption harder to execute.

Whatever uncertainties there are about the final scale, this deal clearly will mean a lot of new arms acquisitions by the Saudi regime. Another question that comes to mind therefore is, what exactly does Saudi Arabia need all these arms for? The country is already the 4th highest military spender in the world. It has a fleet of well over 200 major combat aircraft, with more on the way.[1] Saudi Arabia has more UK-made planes at its disposal than the UK Air Force. The quick answer is ‘Iran’, but this is absurd: Iran spends $13 billion a year on the military, and its arsenal consists mostly of obsolescent Cold War era equipment, due to the effect of international arms embargoes. According to SIPRI data, Saudi Arabia took delivery of over 13 times the volume of major conventional weapons as Iran between 2007 and 2016. Over this period, Saudi was the 2nd largest recipient of arms transfers worldwide, while Iran was the 50th, behind Finland, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan.

It is true that Iran has some domestic arms production capabilities, and have in particular developed a range of ballistic missiles, which makes some Saudi purchases, such as the THAAD, understandable; but overall, Iran faces an overwhelming military disadvantage compared to their Saudi and allied Gulf rivals, not to mention the US forces stationed in the region. If this arms build-up is about ‘deterring Iran’, one must ask, just exactly how much deterring does Iran need?

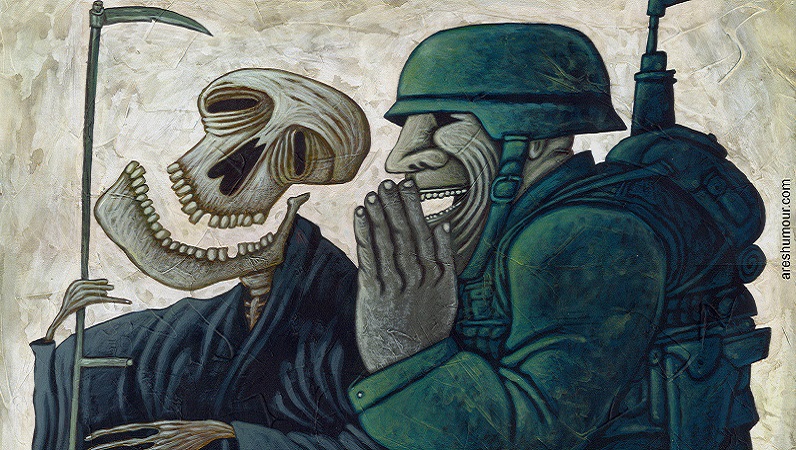

This sense that Iran is being built up into a massive, terrifying bogeyman, against which there is almost no limit to the amount of firepower necessary to defend, is enhanced by the talk of creating an ‘Arab NATO’ that has been floating around the Trump visit. This would supposedly be a Sunni alliance, including countries such as Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt and Jordan, aimed at fighting ISIS and deterring Iran. All this represents a highly dangerous approach to the region: that Iran is an implacable foe, with whom there can be no possible rapprochement, only endless cold, or possibly hot, war; that there is an inevitable enmity between Sunni and Shia; that the solution to the Middle East’s problems is more arms and more war.

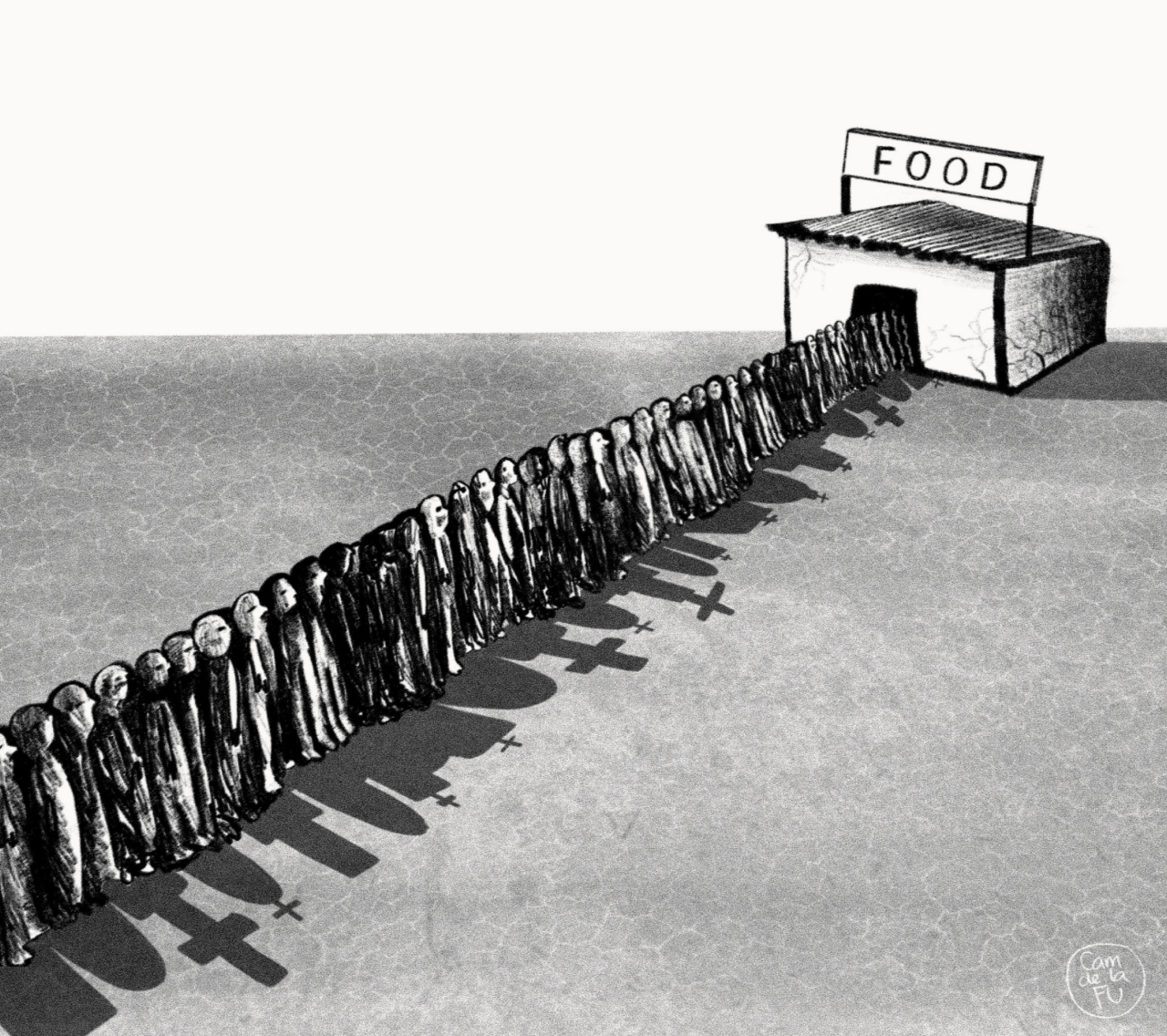

Nowhere is this paradigm more devastating than in Yemen, where the massive Saudi-led air campaign, founded on an exaggerated fear of Iranian influence, has turned a civil war into a devastating humanitarian catastrophe, with over 10,000 civilians directly killed, and millions threatened with famine. The overwhelming air power of the Saudi-led forces has not succeeded in breaking the deadlock between the government of President Hadi they are supporting, and the opposing Houthi forces, allied to supporters of former President Saleh. Tthere is no reason to believe that more arms are going to change this.

Negotiations, ceasefires, and efforts towards a peace deal are desperately needed in Yemen—as are, in the longer term, efforts to dial down the dangerous tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and to find peaceful approaches to their very real differences. But the message conveyed by the Trump visit and the arms deals is the exact opposite.

[1] Exact numbers vary according to source. According to SIPRI, they have received 156 F-15C Eagles and Strike-Eagles, 70 Eurofighter Typhoons, and have 84 Tornado IDS aircraft currently being modernized.