In the first part of this article, I explained why it is difficult to estimate the total annual financial value of the global arms trade. In part 2, I explore in greater detail the challenges associated with various national context and focus on assessing the record of the world’s number one arms trader: the United States. I then present my attempt to obtain a reasonable ballpark range of estimates for the financial value of the international arms trade, based on the available data, flawed as it is.

Data for the United States

The US, which is by any measure the world’s largest arms export, provides highly detailed data on their arms exports, covering orders, licenses, and deliveries. The problem is, some of this data is really, really, bad.

US arms sales go through two different channels: Foreign Military Sales (FMS), which are government-to-government agreements, where the US sells equipment to a foreign government, and then subcontracts the production of the equipment to a US arms producer. The second is Direct Commercial Sales (DCS), where exports are agreed directly between a US company and the recipient government, requiring a license from the US government.[1]

Data on FMS agreements and deliveries are available annually from the Defense Security Cooperation Agency, and as far as we know, this data is comprehensive and reliable, and is regularly revised and updated as new information becomes available.

The problem comes with DCS. The State Department produces an annual “Section 655” report each year detailing the value of authorizations and deliveries of defense equipment and services under DCS. The value of authorizations for each country is broken down into different categories of military equipment and services, with number of licenses and value in each category for each country. Data on shipments (deliveries), however, is limited to a total per country. Up to 2008, the DCS delivery figures are also reported in the DSCA Fiscal Year Series reports.

The CRS does not include data on DCS agreements and deliveries in its total for US arms exports, as it considers the data to be incomplete, and as the data is not revised and updated as is the case for FMS data. In particular, data on DCS authorizations is of limited value, as once a company has obtained a license for export with a 4-year validity, it is under no obligation to report whether or not a contract has resulted from this license, or the value of any such contract. An even more serious problem is that they include licenses for deliveries by US companies to US forces and government agencies stationed overseas. This gives rise to particularly high figures for countries such as Japan, South Korea, the UK, Germany, Belgium, Afghanistan and Iraq, which are host to a large US military presence. This is especially true for the authorizations for DCS agreements for defense services, which are frequently much larger than those for defense equipment. In general, there is no way to distinguish between authorizations for actual exports to foreign governments, and those for contracts between US companies and US forces overseas.

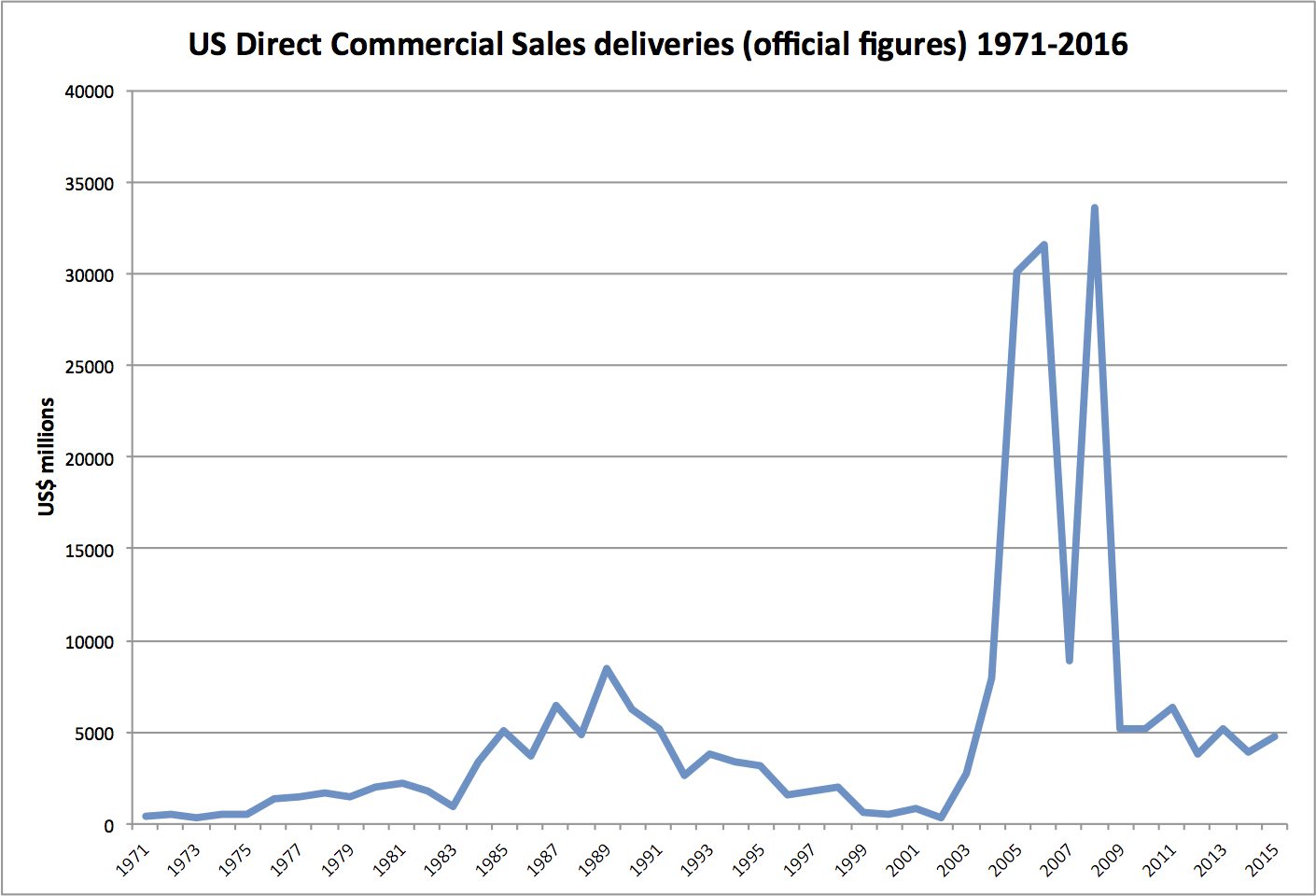

We are interested in deliveries, however, for which separate figures are provided, at least for defense equipment (articles); data for deliveries of DCS defense services are not available, as no-one collects this data.[2] Unfortunately, this data is incomplete, as it is based on voluntary reporting by companies at the point of shipment. As a result, the figures are in general substantial underestimates of total DCS deliveries. Figure 1 shows the value of official figures for DCS deliveries from 1971 to 2015, from which the highly erratic nature of these figures is evident.

In particular, there is a huge spike in the figures for 2005, 2006 and 2008. In these years, following pressure from US Congress for better data, detailed and comprehensive shipment data for DCS was collected by the US Customs, and presented in the section 655 report. The figures for these years are each over $30 billion, compared to a maximum of $8.9 billion in any other year for which figures are available.

However, as with the figures for authorizations, these figures are greatly inflated by the inclusion of deliveries by private companies to US forces and government agencies operating overseas, as well as actual exports to foreign governments and entities. Indeed, as with authorizations, the largest recipients of DCS deliveries in 2005, 2006 and 2008, and the ones showing the biggest ‘spike’ in deliveries for these years, are mostly countries with a significant US troop presence and/or military bases, such as Japan, Germany, the UK, South Korea, Kuwait, and Italy. Thus, these figures are massive overestimates.[3]

There is, however, good data available on DCS deliveries for exactly five years. The General Accounting Office (GAO), carried out an analysis in 2010 where it systematically went through all records of DCS-licensed shipments contained in the Automatic Export System database from 2005-2009, stripping out deliveries to US forces overseas, and temporary exports (e.g. for demonstration to clients, or display at arms fairs), to obtain estimates for the level of actual, permanent exports in each year to foreign governments and entities. The figures they obtained were: $10.6 billion in 2005; $11.7 billion in 2006; $12.2 billion in 2007; $12.1 billion in 2008; and $13.3 billion in 2009. These figures do not include $4.1 billion of equipment shipped to Canada over the period 2005-09, which were exempt from license requirements under a special US-Canada mutual arrangement.

The figures for 2005, 2006 and 2008 are much lower than the totals produced by Customs. On the other hand, the figures for 2007 and 2009 were significantly higher than the official figures produced under the voluntary reporting system, of $8.9 billion and $5.2 billion respectively. This confirms that this voluntary system leads to highly incomplete and underestimated data.

The ratio between the GAO and the official figures, however, is far higher in 2009 than that in 2007, showing that there is no consistency in the degree of under-reporting in most years. Looking back over the official figures in general, the dip in DCS deliveries to less than $1 billion a year over the period 1999-2002 is also hard to interpret. This raises the suspicion that variation in the official DCS figures over the years is as much due to the ‘noise’ of the extent to which companies are bothering to report shipments, as to the ‘signal’ of the actual level of arms sales—and that it is thus impossible to distinguish the two.

In short, the official DCS delivery figures, like the authorization figures, are essentially useless for estimating the true level of US arms exports. As noted above, these figures also exclude exports of military services, which are almost certainly a significant amount: the export of equipment is frequently accompanied by the provision of long-term maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) services, as well as training in the use of the equipment, technical assistance, etc. But there is no good way to estimate this.[4]

In other words, nobody knows the actual level of arms exports by the world’s number one exporter. The GAO report, as well as the annual CRS reports, lament this state of affairs, pointing out that knowing what arms the US is actually exporting would help both administration and Congress to assess whether these exports are supporting or harming US foreign policy goals. But as yet, this has drawn no response.

Figure 1: US Direct Commercial Sales deliveries, 1971-2015 (official figures)

So just how big is the international arms trade?

“We don’t know” seems a bit of a cop-out. Is it possible to make a reasonable estimate, or at least a range of estimates, based on the available, incomplete, information? SIPRI, while focusing mostly on their TIV figures, collate national reports on arms exports, and estimates, based on these that the total financial value of the global arms trade in 2014 was likely to be at least $94.5 billion.

I tried to go into more detail on this question, poring (and often despairing) over the available data, to try to derive a reasonable estimate for the period 2012-15. The details of this are described in an occasional paper, now available on the WPF website. For the US DCS, I went through the detailed arms transfer records in the SIPRI database to assess how the level of DCS transfers has changed since the period covered by the GAO report, when such sales averaged $12 billion a year, concluding that, at least by the SIPRI TIV measure, the level has gone down somewhat, indicating probably little change in the financial value—though with a wide margin of error. For those countries that report deliveries (and for US FMS sales), these figures may be used directly. For Germany, I extrapolated from delivery data that is provided for a subcategory of arms exports, “weapons of war”. For countries reporting only orders (the UK, Israel and South Korea), I built estimates, again with a wide margin of error, based on an analysis of the pattern of time lags between orders and deliveries, again making extensive use of the SIPRI database. For China, I took a range based on estimates (of uncertain methodology and quality) from other sources.

However, the DCS Services problem is one that can’t easily be got round: there is simply no viable way to produce even a meaningful range of estimates. Moreover, it is likely that most military services are excluded from other countries’ deliveries data. Military services are however included in US FMS delivery data, and in the UK figures on arms export orders, and are likely to be a very substantial proportion, especially to Saudi Arabia.

My final estimate: the total value of the legal global arms trade, excluding military services under US DCS and other countries that do not report such services, probably lies in the range $86-105 billion per year. The missing services certainly run into the billions, and probably the low tens of billions. But more than this one cannot say with any confidence. The data is, as I say, really, really, bad.

[1] There is also the much smaller Excess Defense Articles program, involving transfers of surplus US equipment, for which there is good data.

[2] Military services include those such as after-sales maintenance, repair and overhaul, training, technical assistance, and logistics.

[3] It would appear that deliveries to US forces have not been included in other years, although it is impossible to be certain that all such deliveries have been excluded.

[4] The GAO report notes that about a third of the value of FMS exports analyzed were for services, but it is likely that the figure is lower for DCS exports, which tend to go to developed countries, and often involve subsystems for inclusion in larger platforms.