On the November 22, 2017, the Guardian published an article that quotes Alex de Waal as arguing that the UK, US and others on the Security Council, Below is the article on the topic, and you can also access a podcast interview with de Waal:

Britain is in danger of becoming complicit in the use of starvation as a weapon of war in Yemen, academic and author Alex de Waal has said.

“The UK and the US, and others on the security council risk becoming accessories to the worst famine crime of this decade,” said De Waal.

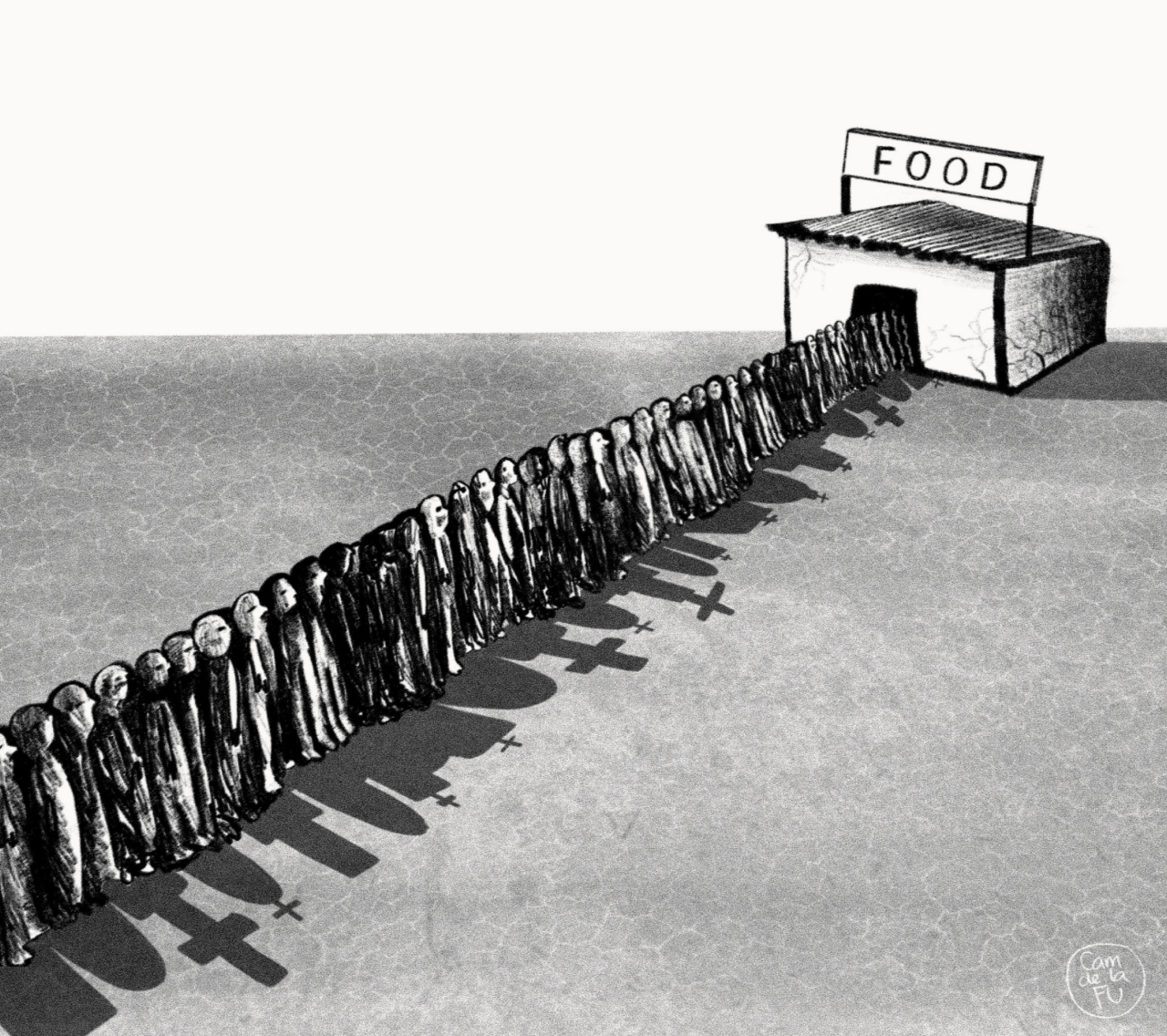

Yemen has been crippled by fighting between a Saudi-led coalition and Houthi rebels, which has brought the country to the brink of famine and left it in the grip of the world’s worst cholera outbreak.

Earlier this month, the coalition closed all Yemen’s borders, preventing humanitarian aid from arriving in the country. The UN called for the blockade to be lifted to prevent the deaths of thousands of people and, while Saudi Arabia announced on Thursday that some key air and seaports would be reopened to allow the delivery of food and medicine, agencies have warned only unrestricted access will avert famine.

“If you see someone starving, it’s not just that they’ve got a disease. Somebody has done it to that person. Yemen is really the most shocking case of our generation of a famine crime because the lines of culpability are so clear and there’s no denying them,” said the longtime Africa analyst, in London to promote his latest book.

Twenty years after publishing his influential Famine Crimes, De Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation, has returned to the subject with Mass Starvation: The History and Future of Famine, published on Friday.

Cataloguing the famines that have killed 100,000 or more people since the 1870s, De Waal’s research showed that famine killed 10 million people every decade until the 1980s, but had almost disappeared by the early 2000s.

This positive trend has been disrupted recently by war, blockades, hostility to humanitarian principles, and a volatile global economy.

De Waal concedes that Yemen was food insecure, mismanaged and in economic crisis. But he argues that people have reached starvation point due to the military campaign on both sides. Air attacks, he said, are destroying roads, markets, hospitals – all crucial for civilians to survive – and, critically, the main port of Hodeidah.

“Repeated attempts by the United Nations to get expedited clearance for humanitarian access for reconstructing the port have been blocked,” said De Waal.

“Yes, the UN security council has tried to find ways around it, but frankly they have not cared enough really to force the hand of those who are inflicting famine on Yemen in order to get them to stop.”

The problem with prosecuting starvation is “that we don’t care enough to do it”, he said. “We should be saying to our political leaders and to the judges at the international criminal court, ‘You ought to be looking for who is responsible politically and criminally for the starvation in Yemen and bringing them to court’.

“And if it embarrasses not only our allies in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates but our own governments here [UK] and in Washington as well … Well, so be it.”

In Famine Crimes, De Waal argued that the global relief industry had substituted itself for the political action needed to prevent famine.

Twenty years on, he attributes relatively low famine mortality, despite ongoing conflict in places such as South Sudan and Somalia, to the fact that action by the UN and NGOs has become “more informed, more professionally effective than it ever was before”.

De Waal said he still believes famine can be abolished, but that we need “a more humane capitalism” to avoid food price spikes and to address climate change.

He called for wars that “trample on humanitarian values” to stop.

The “humanitarian imperative” has to be above all else, “including above restrictions imposed on humanitarian action by the war on terror by this country [UK] and by the United States.

“If we go down the path of a deal-making, transactional politics where every international engagement is run on the basis of ‘what’s in it for us’, then I’m afraid we’re going to have another era of famines in the world.”