I recently went to Washington, D.C. for a series of meetings, and took the opportunity to steal away a few hours to visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) for the first time. This extraordinary institution required much more than the time I had available to tour it (and I hope to get back), but even a truncated visit was a powerful experience. Here I present a few thoughts on how it resonates with memorial museums focused on mass atrocities, an area that I have some experience with. the NMAAHC has all of the main elements of a memorial museum: history(ies) of state-sponsored violence, told from the perspective of victim groups, encased within stunning architecture and graced with a memorial space.

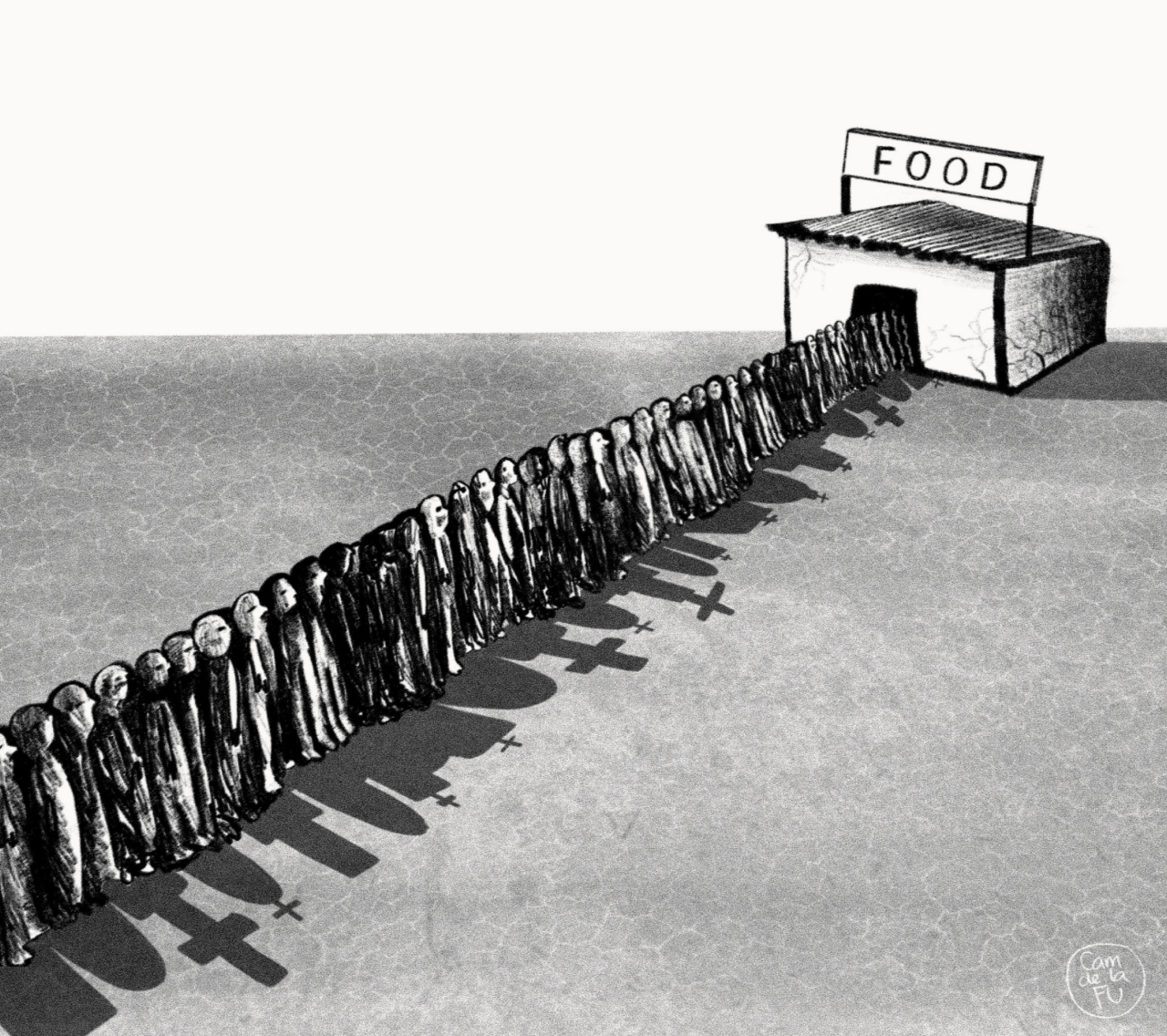

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”4″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]Most memorial museums that I’ve visited focus on a single, devastating event that lasts no longer than a couple years: as examples, the Holocaust, the Rwandan genocide, the Khmer Rouge regime, and the period of the Red Terror in Ethiopia. Having a focused historical period allows these institutions to tell their stories in great detail. The broader historical context generally appears only in a condensed manner, with the presentation implicitly or explicitly rationalizing the focus by arguing that the series of events and forms of violence are exceptional–a departure from a national (or multi-national) historical arc.

The NMAAHC also begins its permanent exhibition by presenting a mass atrocity: the trans-Atlantic slave trade. But given that its mission is to African American life, history, and culture, institutionalized slavery is only a starting point, out of which emerges a much longer tale with no ‘ending.’ Here, atrocity is foundational. Violence is not an anomaly, but a mode of political, economic and social governance. Multiple strands follow from this and distinguish the NMAAHC from a typical memorial museum.

For one, the emotional arc of the permanent exhibition is more troubled than many memorial museums: the end is uneasy, every gallery includes multiple directions. This is not to belittle the emotional impact of, for instance, Holocaust memorial museums or torture centers turned into museum sites, but to note that their presentations tend to tell powerful, solemn and sometime relentless narratives of suffering that end with the conclusion of a period of concentrated harm. The NMAAHC moves in multiple directions. Chronology and narrative ‘progress’ cross paths and overlap, but also diverge into a series of detours.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”5″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]Another outcome is that the opposition of social ideals and violent history is less easily resolved. There is no dramatic crumbling of ideals, where democratic institutions fell apart suddenly under the strain of brutal dictatorship or war, nor can ideals be reconstituted by a new regime. Democratic ideals co-exist with atrocities: the promise of equality and human rights pierce with stunning betrayal and, nonetheless, twilight hope. As a visitor exits the section documenting the transatlantic slave trade into the era of American independence, cramped and dark halls suddenly give way to enormous space, replete with life-sized statues of ‘fathers of democracy’ and the aspiration that ‘all men are created equal,’ even as the history documented in the Museum glaringly presents the co-existent hypocrisy. The sum effect is a lofty pain.

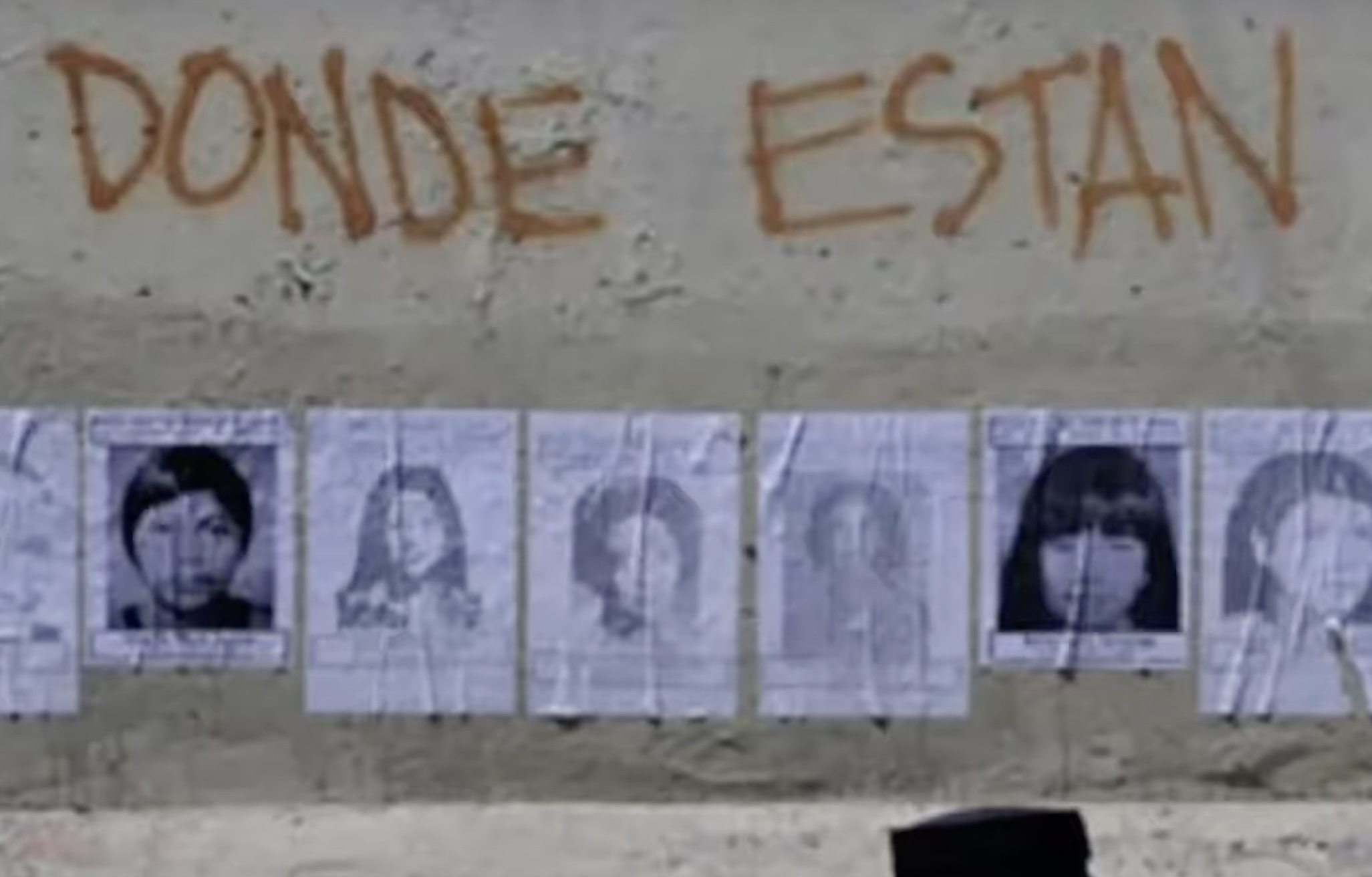

At the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, where I worked for ten years, my favorite gallery was always the tower of faces: a multi-story space where all fours walls present more than 1500 images from the collection of a local photographer in Polish shtetl, Ejszyszki. Walking into the tower, the solemnity of formal portraits mingles with joyful occasions of a pre-war Jewish community. The life portrayed in photos provides stark contrast with the machinery of death under the Nazi occupation, and allows a tiny glimmer of the worlds destroyed. The NMAAHC is able to create a similar impact throughout its exhibitions by documenting not only violence and subjugation, but also empowerment, agency, joy and celebration. This occurs in concentrated form in the Cultural Expressions exhibition — where I, like many of the younger visitors there that day (at least from what I observed), spent a lot of time. Visitors appeared to be having a lot of fun—something rarely permissible in a memorial museum. The exhibitions of contemporary art, performing arts, and music all burst with energy. It is truly spectacular and a compelling model for why museums that narrate violence should also celebrate vivacity and cultural expression.

If the NMAAHC is viewed alongside history museums, it brilliantly makes the case that the diversity and complexity of African American experiences, and their central–yet too often under-noted–role in American history, can only be told through dedicated focus. If viewed as alongside memorial museums, the NMAAHC presents a distinct perspective on how violence and resistance to it should not be viewed as exceptions to democratic practice, nor as ‘ended’ when a ‘bad regime’ is overthrown. It argues for contextualizing moments of exceptionally high levels of violence, understanding how formal democracy is just the beginning of meeting challenges of responding to state-sponsored violence. In so doing, the Museum issues a call to tell more complicated public histories as the starting point for arriving at more nuanced and enduring responses to public challenges.