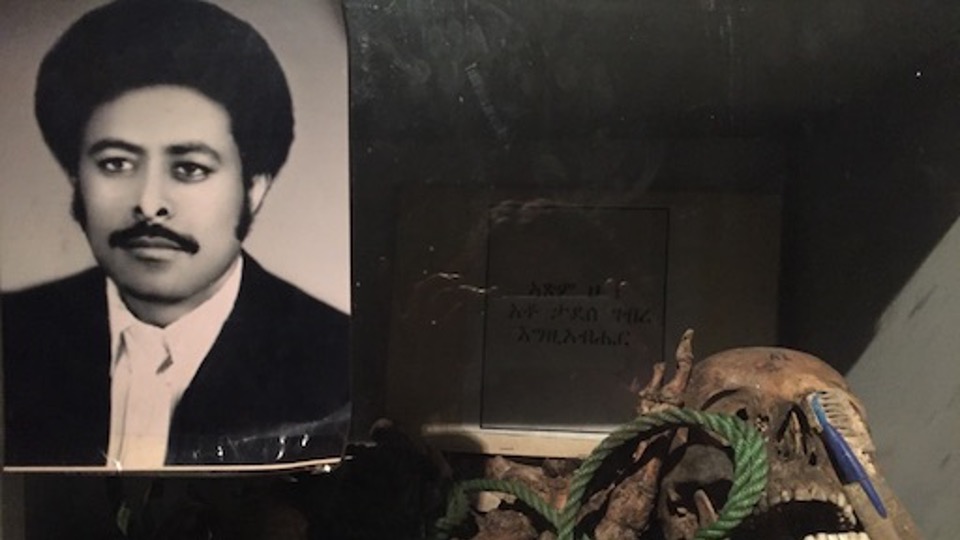

Image: Man killed during the Red Terror in Ethiopia, photo and skull as displayed by the Red Terror Martyrs Memorial Museum in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (Bridget Conley/World Peace Foundation).

Ethiopia’s history includes too many dead from political violence. There are long histories, but even if we start only from the overthrow of the imperial regime in 1974, the lines are traumatic, winding their way through cities strewn with bodies of children killed at night, famine ravaged villages, battlefields in the north, east and west, various ‘security forces’ and special police units that operate outside any legal boundary, summary executions and torture hidden behind prison walls. The country’s political language is replete with violence: in the name of security, development or ethnic advantage. The tables turn—but then they turn again and again, and the language remains the same, even if a new turn of phrase, speaker or target arises.

The dead don’t leave. They haunt and make each shift in the political winds more difficult to weather. As I write, another generation of young Ethiopian men (it is mostly men) are killing each other, turning their guns on civilians, raping women and girls, and destroying what is needed for people to eat food, drink water and sleep safely at night. Some stories from the conflict suggest that some soldiers within military are trying to behave within the bounds of law, but militias and the forces from neighboring Eritrea are not. Stepping outside, for however brief a moment, from the depths of violence today, what might the past tell us about how today’s dead will speak in future?

My insights are drawn from in-depth study of the Red Terror Martyrs Memorial Museum (Addis Ababa), and a limited comparative review on memorials in Ethiopia. In a new paper, “Slippage: Bones, intentions and the construction of memorial meaning,” published in Violence: An International Journal (February 24, 2021), I try to think about the limits to assigning meaning to memory of atrocities. The paper draws on research that pre-dates the current conflict, but there are some general thoughts that might apply to today’s situation.

First, determining how the dead will matter begins before they even die. Political violence is a way to use life itself as a means to calculate advantage. Yet, the lives gain meaning from many other networks of relationships, including religion, family, friends, colleagues, and neighbors – among only some of the possible networks. Every life lost is entangled in distinct web of meaning.

Second, death in or because of political violence, multiplies and electrifies the possible meanings associated with death. It adds more actors and trauma to the work of assigning meaning. While in some Ethiopian contexts, the idea of “martyr” for a cause envelopes death in political violence, it does not to do so completely. Dying or being killed “for a cause” never finalizes the ways in which the dead have social meaning: it amplifies the trauma around death and the potential for discordant, overlapping and irreconcilable meanings.

Third, however powerful or focused the “intentions” are behind killing or (in the aftermath) memorializing the dead, there is no way to control memory of atrocities. Slippage characterizes memory. The dead may be (again) counted; their remains located and buried, never found, or even placed on display in a memorial that is yet to be built. Depending on who memorializes and when—the dead will gain different meaning. Meaning will be made in the tears of mourning family members, quietly intoned prayers, or boastful assertions of political-military triumph. But it will not stop there. The one thing study of memory of political violence can assert without caveat is that it produces, multiplies and slips in meanings in ways that cannot be predicted by those who set violence into motion. Ethiopia’s history throughout the past decades and today provides terrifying proof of this dictum.