There’s a chance to de-escalate the war in Ethiopia and begin negotiations towards peace. The opportunity is slender but worth taking. It starts with calming the rhetoric.

The alternative is that the public rhetoric escalates and the next phase of the war—in Western Tigray and Tselemti, areas claimed and currently occupied by Amhara regional state—becomes a war of one Ethiopian people versus another.

The Government of Ethiopia announced a unilateral ‘humanitarian ceasefire’ immediately the army fled from Tigray. The use of the two words ‘humanitarian’ and ‘ceasefire’ was a rhetorical device to turn a military disaster into a narrative of political normalcy. Government statements avow concern for the farmers of Tigray while government actions are creating a starvation siege of the region. The government continued to describe the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) as a ‘criminal junta’ and has not rescinded its designation as a terrorist organization, and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has said he is capable of returning to Tigray by force of arms.

Abiy’s own speeches are a combination of belligerence and a calm reassurance to his audience that everything will be fine. He promises that he can raise a huge army—a million men if need be—and crush the Tigrayans at will. He calls on the Amhara to fight for their land. And meanwhile Abiy shows neither panic nor doubt, rather a supreme confidence that everything is unfolding according to plan and providence.

At the United Nations Security Council meeting on July 2, every speaker praised the ceasefire announcement and said it was a beginning. Not a single member of the council accepted the Ethiopian government’s narrative, but the fact that the word ‘ceasefire’ was in an official announcement was an entry point.

The Government of the Regional State of Tigray, back in its capital Mekelle, announced its preconditions for a ceasefire two days later. The Tigray government includes the TPLF and the Tigray Defense Forces as well as other Tigrayans. It identified seven points before it was ready to negotiate a ceasefire. These include: withdrawal of Eritrean and Amhara forces; accountability for crimes committed; humanitarian access; resumption of essential services; respecting the Federal Constitution and allowing the Government of Tigray region to resume its activities; suspension of Federal decisions taken since October 2020 (it singled out the detention of Tigrayans); and an international mechanism to monitor the implementation of these preconditions.

Taken side by side, the statements from Addis Ababa and Mekelle are a reminder of the macho posturing that led to the outbreak of the war and makes one wonder whether anything has been learned from the calamity of the last eight months.

The seven points are reasonable, and the insistence on constitutionalism is a crucially important signal that Tigray intends to remain part of the Ethiopian Federal order.

The language of the announcement sends an entirely different message. It begins with denouncing ‘the fascist clique spearheaded by Abiy Ahmed.’ The rhetoric is bellicose and uncompromising—one of trading punches with an adversary rather than seeking a solution.

Taken side by side, the statements from Addis Ababa and Mekelle are a reminder of the macho posturing that led to the outbreak of the war and makes one wonder whether anything has been learned from the calamity of the last eight months. The rhetoric seems to tell us that the two sides hate each other so much they would rather pull the house down than reconcile.

The war is now in a new and particularly dangerous phase. Having captured virtually all of those parts of Tigray that are uncontestably the historic lands of Tigray, the TDF has turned its attention to the western districts between Shire and the border with Sudan. Since 1991 this has been Western Tigray. Prior to 1991 this area was part of Gondar (or Begemdir) province. With the introduction of the federal system based on ethno-national territories, the area was transferred to the new Tigray regional state. At the time, the leadership of the newly-created Amhara regional state—allies of the TPLF within the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front—protested. The issue has festered ever since.

The complexities of Western Tigray/northern Gondar cannot be fully explained in this post. (See my reflections on self-determination on

this blog and the paper by Mulugeta Gebrehiwot and Fesaha

Gebresillasie on Ethiopia that argues that the local elites in these areas fell prey to the ‘exclusive reactionary nature of administrative nationalism sidelining the project of building a common economic and political community’.) Both sides have claims. Pre-1991 provincial boundaries did not indicate ethno-national identities—being part of Gondar did not automatically make a location ‘Amhara’. One of the failings of the federal system was that areas such as this, with mixed populations, were designated as ‘belonging’ to one regional state or another.

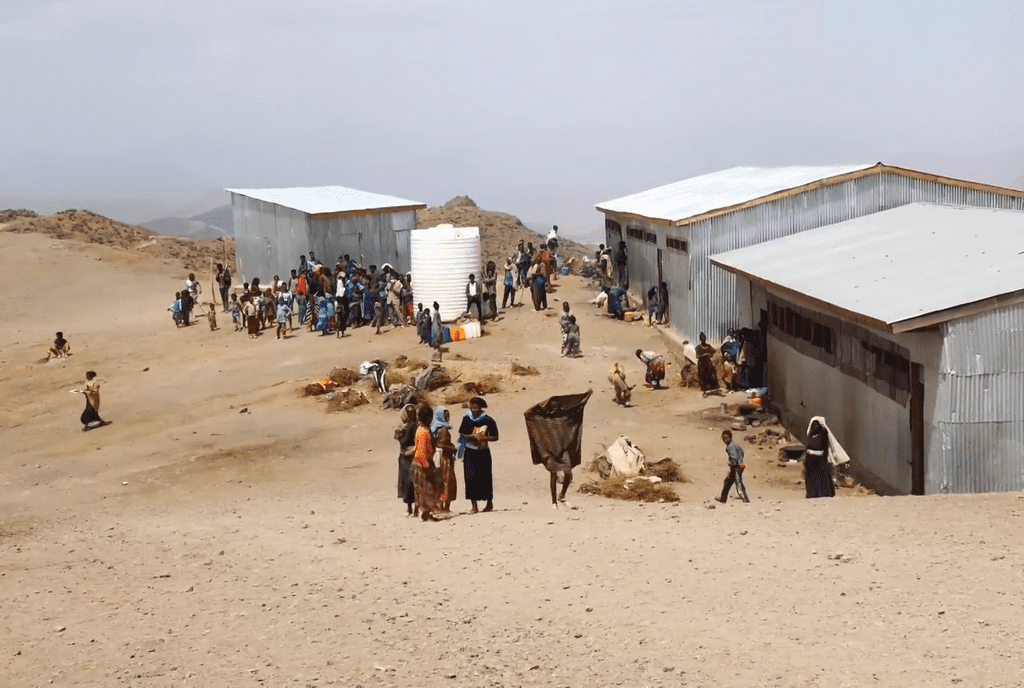

Photo: “A representative of the Amhara Regional Government looks out over the Simien Mountains” by UNESCO Africa is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

When the new map was adopted in 1991, Amhara regional state was unhappy with the boundaries. Its claims were both on the basis of being cut off from an ethnic Amhara population that was now a minority in Tigray and also that the new dispensation did not take account of the historic provincial Gondar identity. It is notable that the constitution of the Amhara regional state begins by referring, not to the Amhara as such, but to all the peoples settled in the territory of the Amhara state. Other regional constitutions begin by referring to the ethno-national group in question.

In short, the status of these districts is contested, with valid arguments on both sides.

What was undoubtedly wrong was the seizure and redrawing of regional boundaries by force and the expulsion of the Tigrayan population, which took place last November.

The status of these areas should be resolved by peaceful and legal means.

The particular danger of the new phase of the war is that the Federal Government in Addis Ababa and the regional Government in Bahir Dar are mobilizing the Amhara citizenry to fight as a people’s army. The previous phases of the war have been the TDF fighting the Ethiopian National Defense Force. It was an existential struggle for the people of Tigray against an Ethiopian state project and an Eritrean occupation. After its recent defeats the army cannot defend its front line and the Amhara regional state has vowed to fight to the death over every mile, while the Tigray government has said it will reclaim every inch of its territory.

We now face the perilous prospect of a war between the Tigrayan people and the Amhara people. A boundary dispute may well become an existential issue for the two ethno-national communities.

This coming phase of the war will be fought on the battlefield, hopefully with both sides respecting international humanitarian law. When people’s militias fight, the casualties are likely to be high. It goes without saying that if the TDF prevails it should not reciprocate the ethnic cleansing of November and expel ethnic Amharas.

This war will also be fought in rhetoric, and this may ultimately be the more significant war. The choice of words by both sides will determine whether the conflict remains limited to its immediate military objectives or escalates to become a war of people against people, which will make it infinitely more difficult to resolve.

The ceasefire should begin by de-escalating the rhetoric.

Photo: “A representative of the Amhara Regional Government looks out over the Simien Mountains” by UNESCO Africa is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0